To the Editor,

The optimal management of unresectable locally advanced disease or borderline resectable disease is unclear. We highlight one such case and discuss the increasing role for preoperative multi-modality therapy.

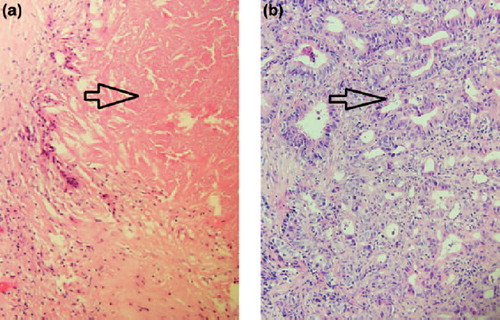

A 60-year-old lady presented with a two-month history of weight loss and epigastric pain. A computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen revealed a mass in the uncinate process of the pancreas extending to the root of the mesentery (). Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspirate confirmed a diagnosis of invasive moderate to poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (). Multidisciplinary discussion determined this case to be a borderline resectable tumour [borderline because of tumour contact to the first branch of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA)]. Conversion chemoradiotherapy (with external beam radiotherapy 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions over 5½ weeks with concurrent gemcitabine administered at a dose of 300 mg/m2 weekly) was advised in an attempt to downstage the tumour and increase the possibility of an R0 resection. Restaging CT scan post completion of chemoradiotherapy showed a response with regression of the tumour particularly at the root of the mesentery and in the specific area relating to the first branch of the SMA (). A radical pancreaticoduodencectomy was performed. Pathological assessment of the surgical specimen revealed a complete pathological response (pCR) (). No adjuvant treatment was administered. Now 24 months from the initial presentation a clinical and radiological complete response has been maintained.

Figure 1. (a). Portovenous phase axial CT pancreas with oral and IV contrast at the time of the initial diagnosis. The CT shows a 2.5 cm exophytic mass arising from the uncinate process of the pancreas (white arrow) which abuts, but does not encase, the superior mesenteric vein and artery (broken arrow). The mass is contiguous with the third part of the duodenum (arrow head). (b). Portovenous phase axial CT pancreas with oral and IV contrast. Following treatment with concurrent gemcitabine and radiotherapy, the mass has decreased in size measuring 2 cm (white arrow). There is now a definitive fat plane between the pancreatic lesion and the third part of the duodenum (arrow head). The tumour abuts but does not encase the superior mesenteric vein and artery (broken arrow). A biliary drain can be seen in the duodenum.

Figure 2. (a). Tumour biopsy pre-conversion therapy. (40×). Invasive adenocarcinoma is arrowed. (b). Lymph node from resection specimen post-conversion therapy. Extensive treatment effect including fibrosis has obliterated normal lymph node architecture. Necrosis (arrowed) is present, consistent with treated tumour and is associated with palisaded giant cell reaction. (40×).

Pancreatic cancer confers a poor prognosis and surgery offers the only potentially curative treatment option. However, two thirds of patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease. For the subset of patients who present with resectable disease the five-year overall survival rate following pancreaticoduodenectomy is 15–20%, however, rates of local and systemic recurrence remain high [Citation1,Citation2]. The survival rate for patients who have an incomplete resection (R1/R2) is similar to that of patients who have locally-advanced pancreatic cancer managed with chemoradiotherapy [Citation3]. Many studies suggest that margin status strongly predicts for early recurrence and a short survival [Citation4–6]. This emphasises the importance of staging evaluation in determining the resectability of the primary tumour.

With advances in staging imaging a new phenotype of pancreatic cancer has emerged called “borderline resectable” tumour which blurs the distinction between resectable and locally advanced disease. There is no consensus definition of borderline resectable pancreatic cancer.

In the absence of a clinical trial, preoperative chemoradiotherapy, for borderline resectable tumours should be considered [Citation7]. In 2008, Evans et al. [Citation8] reported the findings of a phase II study looking at the outcomes of patients who received preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation followed by pancreaticoduodenectomy with early stage resectable pancreas cancer. The median overall survival was 34 months for the 64 patients who underwent surgical resection and seven months for the 22 patients who did not (p < 0.001). The five-year survival for those who did and did not undergo pancreaticoduodenectomy was 36% and 0%, respectively. Lind et al. similarly reported the results of 17 patients with non-metastatic, inoperable pancreas cancer who underwent preoperative chemoradiotherapy with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. Restaging CT scan four weeks following completion of chemoradiotherapy determined 11 patients surgically resectable of which eight underwent an R0 resection. The median OS of this group was 29 months. This compared favourably with a control group with primary resectable disease in whom the median OS was 16 months (75% had an R0 resection) [Citation9]. High response rates have recently been reported with the use of combination chemotherapy, oxaliplatin-irinotecan-bolus and infusional 5-flourouracil (FOLFIRINOX) in the metastatic setting [Citation10]. Hartlapp et al. report the first case of pathological complete response following consecutive neoadjuvant therapy with (nab)-paclitaxel/gemcitabine and FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy regimens for locally advanced pancreas cancer [Citation11]. Studies are underway investigating the role of FOLFIRINOX in the locally advanced setting (www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01688336). Recent retrospective series have also highlighted the role of induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation in those patients with locally advanced disease [Citation12].

A pathologic complete response following neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer is rarely observed and the prognostic significance is uncertain. Zhaq et al. [Citation13] identified 11 patients with a pCR (2.5%) from 442 patients with pancreatic cancer who received neoadjuvant treatment and underwent pancreatectomy from 1995 to 2010. Survival analysis suggested achieving a pathologic complete response is associated with a prognostic benefit as has been reported in other gastrointestinal tumours, e.g. esophageal and rectal cancer. Chun et al. reported a pCR rate of 7% from 135 patients with pancreas cancer treated with chemoradiation followed by pancreatectomy. Pathologic response correlated with R0 resection (p = 0.019), negative lymph nodes (p = 0.006), and smaller tumour size (p = 0.001). On multivariate analysis major pathologic response (95–100% fibrosis) was also the only variable associated significantly with improved survival [Citation14].

The identification of patients who will have predominantly locoregional disease and those patients who will manifest a pCR post neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy is the topic of much study. Collisson et al. [Citation15] have identified molecular subtypes of pancreas adenocarcinoma with differential responses to therapy and clinical outcomes. The association between DPC4/SMAD4 tumour suppressor gene expression and pattern of progression was recognised by investigators from the US [Citation16]. This concept has been looked at in the setting of locally advanced pancreas cancer whereby tumours with intact DPC4/SMAD4 expression had a local dominant pattern of progression while loss of DPC4/SMAD4 expression was associated with distant dominant pattern of disease progression [Citation17]. Gene expression profiling has identified many genes that are differentially expressed in pancreatic cancer, however, the validation of these genes as biomarkers for prognosis or treatment response is incomplete [Citation18].

This case highlights the importance of recognising borderline resectable, locally advanced pancreatic cancer as a distinct entity that may benefit from preoperative therapy. Achieving a pCR after preoperative therapy is a rare event that has been shown to be associated with a better prognosis. Future trials are needed to establish the role of conversion chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic cancer and ultimately identify the optimal treatment regimen. Prospective validation of clinical biomarkers in this setting is also urgently required.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, Hartmann JT, Gellert K, Ridwelski K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: The CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310:1473–81.

- Neoptolemos JP, Moore MJ, Cox TF, Valle JW, Palmer DH, McDonald AC, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid or gemcitabine vs observation on survival in patients with resected periampullary adenocarcinoma: The ESPAC-3 periampullary cancer randomized trial. JAMA 2012;308:147–56.

- Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, Abbruzzese JL. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2004;363:1049–57.

- Millikan KW, Deziel DJ, Silverstein JC, Kanjo TM, Christein JD, Doolas A, et al. Prognostic factors associated with resectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Am Surg 1999;65:618–23; discussion 23–4.

- Takai S, Satoi S, Toyokawa H, Yanagimoto H, Sugimoto N, Tsuji K, et al. Clinicopathologic evaluation after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: A retrospective, single-institution experience. Pancreas 2003;26:243–9.

- Kuhlmann KF, de Castro SM, Wesseling JG, ten Kate FJ, Offerhaus GJ, Busch OR, et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma; actual survival and prognostic factors in 343 patients. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:549–58.

- Gillen S, Schuster T, Meyer zum Buschenfelde C, Friess H, Kleeff J. Preoperative/neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of response and resection percentages. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000267.

- Evans DB, Varadhachary GR, Crane CH, Sun CC, Lee JE, Pisters PW, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3496–502.

- Lind PA, Isaksson B, Almstrom M, Johnsson A, Albiin N, Bystrom P, et al. Efficacy of preoperative radiochemotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Acta Oncol 2008;47:413–20.

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364: 1817–25.

- Hartlapp I, Muller J, Kenn W, Steger U, Isbert C, Scheurlen M, et al. Complete pathological remission of locally advanced, unresectable pancreatic cancer (LAPC) after intensified neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Onkologie 2013;36:123–5.

- Faisal F, Tsai HL, Blackford A, Olino K, Xia C, De Jesus-Acosta A, et al. Longer course of induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation favors better survival outcomes for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Oncol Epub 2013 Dec 17.

- Zhao Q, Rashid A, Gong Y, Katz MH, Lee JE, Wolf R, et al. Pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant therapy in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is associated with a better prognosis. Ann Diagn Pathol 2012;16:29–37.

- Chun YS, Cooper HS, Cohen SJ, Konski A, Burtness B, Denlinger CS, et al. Significance of pathologic response to preoperative therapy in pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:3601–7.

- Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, Gibb WJ, Truitt M, Gu S, et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med 2011; 17:500–3.

- Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, Luo M, Abe H, Henderson CM, et al. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1806–13.

- Crane CH, Varadhachary GR, Yordy JS, Staerkel GA, Javie MM, Safran H, et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin followed by chemoradiation with cetuximab for locally advanced (T4) pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Correlation of Smad4(Dpc4) immunostaining with pattern of disease progression. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3037–43.

- Lopez-Casas PP, Lopez-Fernandez LA. Gene-expression profiling in pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2010; 10:591–601.