Abstract

Background. Patient information in cancer clinical trial is challenging. The value of audio-recording interventions for patients considering participating in clinical trials is unclear. The primary aim of this randomized study was to investigate effects of audio-recorded information on knowledge and understanding in patients considering participation in a clinical trial.

Material and methods. Patients scheduled for information about a phases 2 or 3 trial by one of the 13 participating oncologists at the Department of Oncology during the study period (2008–2013) were eligible. The intervention consisted of an audio-recording on compact disc (CD) of the information at the medical consultation in which the patients were informed about a trial. Knowledge and understanding was measured by the questionnaire, Quality of Informed Consent.

Results. A total of 130 patients were randomized, 70% of the calculated sample size (n = 186). Sixty-seven patients were randomized to the intervention. In total, 101 patients (78%) completed questionnaires. No statistical significant differences were found between the groups with respect to knowledge and understanding. The level of knowledge was relatively high, with the exceptions of the risks associated with, and the unproven nature of, the trial. Overall, patients who declined participation scored statistically significant lower on knowledge.

Conclusion. The present study was underpowered and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Still, 130 patients were included with a response rate of 78%. A CD including the oral information about a clinical trial did not show any effects on knowledge or understanding. However, the levels of knowledge were high, possible due to the high levels of education in the study group. Information on risks associated with the trial is still an area for improvement.

Informing potential participants in cancer clinical trials is challenging [Citation1,Citation2]. Information about cancer clinical trials are often conveyed to cancer patients in vulnerable situations, e.g. when they are newly diagnosed or in connection with information about relapse. In a Swedish study, deficiencies regarding knowledge of risks associated with the trial, the unproven nature of the trial treatment and the duration of treatment were found [Citation3]. The effects of providing audio-visual information for patients considering participating in clinical trials, alone or in conjunction with standard forms of information, have been evaluated and the value remains unclear [Citation4]. At the time of planning this study, audio-recordings were suggested as a means to improve cancer patients understanding of information at the first consultation, routine follow-up and “bad news” consultations [Citation5–8]. In addition, a review of interventions to improve patients’ recall of medical information showed that interventions tailored to the individual cancer patient are most effective [Citation9]. Extended contact with a healthcare professional has been shown as an effective way to improve cancer patients’ knowledge about clinical trials [Citation10,Citation11]. However, in everyday clinical practice with limited resources, extended contacts are difficult to implement. Thus, we aimed to design an intervention, easy to implement and convenient for clinicians, to provide information directly targeting the clinical trial the patient had to decide on.

The primary aim of the information study was to investigate the effects on knowledge and understanding of audio-recorded (CD) information to patients considering participation in a clinical trial. In addition, the use of the CD and patients’ perception of the intervention was evaluated. Patients who consented to participate in a clinical drug trial were compared to those who declined participation with respect to knowledge and understanding. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm (2005/604-31/3) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, registration number: NCT01502254.

Material and methods

Patients

Patients planned for information about a clinical trial in phases 2 or 3 by one of the 13 oncologists who had consented to be recorded during the study period (2008–2013) were eligible. Patients were informed about the audio-recording study and asked for participation before the consultation in which they were informed about the clinical drug trial. All patients who consented to the information study were included. No other inclusion or exclusion criteria, besides those applied in the clinical drug trials were used in the audio-recording study.

The intervention

The intervention consisted of an audio-recording (CD), using a portable voice recorder, of the information given at the medical consultation in which the patients were informed about a clinical drug trial. Consenting patients got their up-coming medical consultation recorded. In general, the consultations lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. All patients received written information about the clinical drug trial they had to consider. The study nurse conducted the randomization during the consultation in another room; leaving the physician blinded to which group the patient was randomized. After the consultation, patients randomized to the intervention (Group I) received the CD to take home while considering participation in the clinical drug trial. Patients randomized to control (Group C) did not receive the CD.

Procedure

When the patients had decided about participation in the clinical trial, questionnaires were mailed to randomized patients, within a week, together with a prepaid envelope. One reminder was sent to those not responding within two weeks. Clinical data were collected from patients’ files.

Instruments

The questionnaire Quality of Informed Consent (QuIC) consists of two parts, comprising eight basic elements of informed consent in clinical trials (“research purpose and procedures, duration, experimental procedures”, “potential risks or discomforts”, “benefits to self and others”, “alternatives to participation”, “confidentiality”, “procedures in the event of research injury”, “study contacts”, “voluntarism”). Each element is assessed in both the first (knowledge) and the second (understanding) part [Citation12]. The first part, knowledge, consists of 20 items with three response categories (“disagree”, “unsure”, “agree”). Fourteen items are study phase independent. The second part, understanding, comprises 14 items where patients rate the extent to which they perceived that they understood elements of the clinical trial. The response format is a five-point scale from “I didn't understand this at all” to “I understood this very well”. Thirteen of the items in the second part correspond to the basic elements in the first part. One item is a global measure of perceived understanding. The QuIC has been validated in the US [Citation13]. The Swedish translation was used in a previous study [Citation3]. In this study, the wording was modified for patients declining participation in the clinical drug trial to “the trial you were informed about and asked to consider” instead of “your clinical trial”.

In addition to QuIC, questions whether the consent form was signed at the first visit or later were included.

Determination of sample size and statistical methods

In a previous study about 30% of the patients responded correctly concerning risks associated with the trial [Citation3]. To detect a difference of 20% points between the control group (30%) and the intervention group (50%), with a significance level of 5% and with a power of 80%, 186 patients were needed.

Correct responses to the knowledge items were assigned a score of 100 while incorrect responses and responses in the category “unsure” were given a score of 0. Responses to items assessing “perceived understanding” were transformed to a 0–100 scale. Multi-item scales were calculated by summarizing mean values divided by the number of items. A variable, “information sources”, was constructed by assigning a value of 1 if any of the five questions were responded with “yes”. Descriptive statistics were used to compare Group I with Group C. For categorical data group differences were tested using the Fisher's exact test. Mann-Whitney test was used for ordinal or continuous data differences. The difference in proportion and confidence intervals in the variable underlying the sample size calculation was estimated using a generalized linear regression model with identity link and binominal distribution. All reported p-values are two-sided and all analyses of differences between randomization groups were performed using intention-to-treat. Only responding patients were included in the final analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

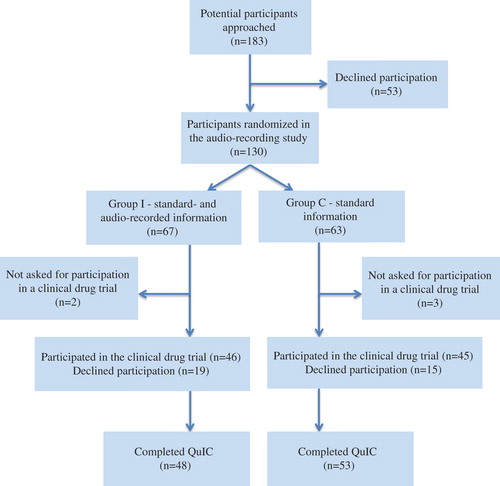

A total of 183 patients were invited to participate, out of whom 53 (29%) declined participation in the audio-recording study. Thus, 130 (71%) patients were randomized, 67 to Group I (intervention), and 63 to Group C (control). The consort diagram is displayed in . A total of 16 medical drug trials were represented, 14 randomized trials of which 10 were phase 3 trials. Thirteen oncologists included patients in the study. Seven of them included 10 or more patients in the study, 82% of the patients: one oncologist included 30 (23%); one included 23 (18%); one included 15 (12%), one included 14 (11%), one included 13 (10%), two included 10 (8%) patients. Six oncologists included less than 10 patients: one included six, one included three, two included two, and two oncologists included one patient each. Patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics are presented in . There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics. Five patients were randomized in the present study, but later not asked to participate in a drug trial (“too ill” n = 3, “language problems” n = 1, “administrative failure” n = 1). Due to slow recruitment rate, the estimated sample size was not reached.

Table I. Patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics.

The informed consent procedure

A total of 46 (69%) patients in Group I and 45 (71%) in Group C consented to participate in the clinical drug trial. Of these, 11 (24%) in Group I and 12 (27%) in Group C signed the consent form in connection with the first consultation. In both groups 29 patients (63% in Group I and 64% in Group C, respectively) responded that they did not sign at the first medical visit. There was no statistical significant difference in the time reported to signing the consent form, six days in Group I (SD = 4.4) and four days in Group C (SD = 3.6).

Knowledge and understanding

shows the proportions of correct responses to questions about knowledge by randomization group. Overall, knowledge levels were relatively high (≥ 80%) for seven of the 14 phase independent items. Lower levels of knowledge (< 50%) were reported regarding risks and discomforts involved in participation, the unproven nature of the trial, about confidentiality with respect to medical records and economic insurances. In , mean scale scores by randomization group are presented for questions about perceived understanding. The levels of perceived understanding were generally high. Mean scale scores for all items were about 80 or more, except for economic insurances, with a score of 65. Mean scale scores, standard deviations and medians for the basic elements for both the knowledge and understanding parts of the QuIC are displayed in . There were no statistical significant differences between the groups neither on individual items nor with respect to the elements included in the knowledge section. The difference between the groups in the variable concerning risks with the trial was 13% (95% CI −5–32).

Table II. Knowledge and understanding in the Quality of Informed Consent (QuIC) questionnaire by element and randomization group.

Use and perception of the audio-recording

A total of 29 patients (43%) reported they had listened to the complete recording, and 6 (9%) indicated they had listened in parts. Fifteen patients (22%) had not listened at all. Seventeen patients (25%) did not respond to this item. Ten patients (29% of those who used the audio-recording) listened more than once. Nineteen patients reported that a relative had listened, all of them had listened themselves too. Responses to items asking about the audio-recording for patients in Group I are shown in .

Table III. Responses to items asking about the audio-recording among those 35 patients who reported having listened.

Differences in knowledge and understanding between patients who decided to participate in a clinical trial and those who declined

Patients who decided to participate in a clinical drug trial (n = 81) reported statistically significant higher proportions of correct responses on five of the phase independent items; “participation beneficial for future patients” (p = 0.007), “review of medical record” (p = 0.001), “alternatives to participation” (p = 0.008), “insurances” (p = 0.04), “decline participation by not signing the consent form” (p = 0.001). The mean level scores for perceived understanding were statistically significant lower for patients who declined participation in a drug trial (n = 20) regarding; “potential benefits to self” (p < 0.001) and “others” (p = 0.007), “confidentiality of medical records” (p = 0.014), “insurances” (p = 0.005) and “overall perceived understanding” (p = 0.048).

Discussion

Only 70% of the calculated sample size was included, as the study was terminated prematurely due to slow recruitment. The results should therefore be interpreted with caution.

No effects were found on knowledge and understanding of providing patients with a CD including oral information on a clinical trial. Overall, participants reported high levels of knowledge and understanding, and we found no differences between the randomization groups. It is therefore plausible that the oral and written information was sufficient and that there was a ceiling effect. Patients who consented to participate in clinical trials reported higher levels of knowledge and understanding on several elements compared to those who declined. About half of the patients in the intervention group (Group I) reported having listened to the CD before taking the decision to participate in a clinical trial or not. However, patients who listened to the recording reported it to be useful for comprehension, increasing knowledge, contributing to informing relatives and not upsetting.

Although earlier studies on newly diagnosed cancer patients and patients in routine follow-up have shown good results of audio-recorded consultations [Citation5,Citation6,Citation8], studies of the informed consent procedure in clinical trials have to date not shown clear benefits [Citation4,Citation14]. This is in concordance with the results of the present study. Only about half of the patients reported having listened to the recording, in total or partly. There might be several reasons for not listening. The recording might evoke negative emotions from this consultation, and the patient can therefore feel reluctant to listen. The recording contained not only information about the trial, but also about other issues that might have been difficult to comprehend. Another possibility is that the information conveyed did not contain all the important aspects of informed consent, and relates to the including physician.

The lowest proportions of correct responses concerned risks and discomforts involved in participation, the unproven nature of the trial, confidentiality with respect to medical records, and economic insurances. To understand and accept the experimental nature of treatment in this vulnerable situation might be difficult. The results indicate that these are challenging areas that need to be improved. It might be possible, that oncologists who would like to include patients in clinical trials tend to underestimate the importance of these issues, and prioritize information that benefits consent. Communication courses for physicians have improved the quality of patient information in clinical trials [Citation15]. When comparing knowledge expressed as basic elements, participants in the present study appeared to have somewhat higher levels than in our previous study on most elements, with the exception of “voluntary nature of participation in the trial”, where the levels were high and comparable [Citation3]. Levels of understanding appeared similar across both studies. As concluded in the previous study, patients seem to experience that they have understood more than what is actually mirrored in the assessment of knowledge.

In the present study, the risk of compensatory rivalry in the control group was negligible, as they did not have access to the recording before taking the decision and responding to the questionnaire. There is a risk that the questionnaire was not sensitive enough to detect differences between the groups. The QuIC is, however, validated and has been used in a number of studies [Citation2,Citation3,Citation13,Citation15].

The sample size was determined based on one of the items in the questionnaire, as the multidimensionality of the concepts of interest, knowledge and perceived understanding, make them inappropriate for sample size calculation. This is a limitation of the study.

An explanation for the relatively high level of knowledge in our study group might be the large proportion, 48%, of patients with higher education. In 2010, 25% of the Swedish population aged 25–64 years, was estimated to have a higher education, i.e. ≥ 3 years [Citation16]. However, in an earlier study, we found that levels of education were not associated with knowledge about cancer clinical trials [Citation17]. The proportion of higher educated patients raises a concern about selection of patients who are asked to participate in cancer clinical trials. This selection could also be a bias for participating in the present study of audio-recorded information. However, in our previous study, in which all patients accepting participation in a clinical drug trial were included, the proportion of highly educated participants was similar [Citation3]. Thus, education bias seems less likely in the present study.

A recurrent problem in studies of the informed consent process appears to be physicians’ compliance with the study protocol [Citation14,Citation18]. The recruitment was slow in the present study, partly due to physicians who hesitated to be recorded, although the study was based on the assumption that it should be beneficial for patients’ knowledge to listen to the oral information more than once. This was our assumption, but not necessary shared by the physicians, who already might have perceived their information sufficient. Some might also have declined participation because they did not like the idea of being listened to by others, including the project group. In addition, there were organizational reasons, as some clinics were so busy that it was not possible to run the study in their context.

There were no differences between the groups with respect to patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics. However, data were missing for a large proportion of patients (18–28%) with respect to education and marital status (self-reported). Thus, there is a risk for bias with respect to these variables, but this is a randomized study and therefore the risk for selection bias should be limited.

Patients who declined the drug trial had lower proportion of correct responses and lower levels of understanding, irrespective of randomization group. This finding may be due to patients’ predetermined negative attitude to clinical trials. It may also be due to insufficient information. In the latter case, it might be possible to raise the recruitment by better information and increasing patients’ knowledge.

Due to the limited sample size, it was not possible to adjust for the information given by the physician or the clinical trial being informed about. This is unfortunate, as these variables might have had impact on the outcomes and might have biased the results. In addition, it was not possible to perform subgroup analyses between those who listened to the CD and those who did not, due to the small sample size.

The present study was underpowered and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution. The results showed that providing patients with a CD including the oral information about the clinical trial they were asked to consider did not appear to have any effects on patients’ knowledge or understanding. Levels of knowledge were high, with the exception of risks associated with the trial and the unproven nature of treatment in the trial. The generally high levels of knowledge and understanding were possible due to the high education level in the study sample.

New methods to improve patients’ knowledge during the process of informed consent, especially concerning risks and discomforts and the unproven nature of treatment in clinical trials are needed. The problems associated with information in this delicate situation might be of a magnitude not possible to overcome by means of technical devices. Instead, personal consultations in which the patients are asked to summarize the information given might be a way to improve and assure patients’ knowledge and understanding before taking the decision to participate in a clinical trial.

Acknowledgement

We thank research nurse, Sara Westin, for informing potential patients and for data collection. We also thank medical oncologists, Tomas Jansson, Elisabet Lidbrink, Theodoros Foukakis, Jan-Erik Frödin, Jeffrey Yachnin, Birgitta Wallberg, Edward Baral, Tone Fokstuen, Jonas Bergh, Maria Gustafsson Liljefors, Judith Bjöhle, and Henrik Ullén for participating.

Declaration of interest: This study was supported by research grants from: the Swedish Cancer Society, the King Gustaf V's Jubilee Foundation, Stockholm County Council, and the Swedish Cancer & Traffic Injury Society Fund. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Hutchinson C, Cowan C, McMahon T, Paul J. A randomized controlled study of an audiovisual patient information on informed consent and recruitment to cancer clinical trials. Br J Cancer 2007;97:705–11.

- Hoffner B, Bauer-Wu S, Hitchcock-Bryan S, Powell M, Wolanski A, Joffe S.“Entering a clinical trial: Is it right for you?” – A randomized study of the clinical trials video and its impact on the informed consent process. Cancer 2012; 118:1877–83.

- Bergenmar M, Molin C, Wilking N, Brandberg Y. Knowledge and understanding among cancer patients consenting to participate in clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:2627–33.

- Ryan R, Prictor M, McLaughlin KJ, Hill S. Audio-visual presentation of information for informed consent for participation in clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;23:CD003717.

- McClement SE, Hack TF. Audio-taping the oncology treatment consultation: A literature review. Patient Educ Couns 1999;36:229–38.

- Ong LML, Visser MRM, Lammes FB, van der Velden J, Kuenen BC, de Haes JCJM. Effect of providing cancer patients with audiopated initial consultation on satisfaction, recall, and quality of life: A randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:3052–60.

- Knox R, Butow PN, Devine R, Tattersall MHN. Audiotapes of oncology consultations: Only for the first consultation? Ann Oncol 2002;13:622–7.

- Tattersall MH, Butow PN. Consultation audio tapes: An underused cancer patient information aid and clinical research tool. Lancet Oncol 2002;3:431–7.

- van der Meulen N, Jansen J, van Dulmen S, Bensing J, van Weert J. Interventions to improve recall of medical information in cancer patients: A systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology 2008;17:857–68.

- Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants’ understanding in informed consent for research. A systematic review. J Am Med Assoc 2004;292: 1593–601.

- Nishimura A, Carey J, Erwin P, Tilburt J, Murad H, McCormick J. Improving understanding in the research informed consent process: A systematic review of 54 interventions tested in randomized control trials. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:28.

- Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clarke JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent: A new measure of understanding among research subjects. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:139–47.

- Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent in cancer clinical trials: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2001;358:1772–7.

- Hack TF, Whelan T, Olivotto IA, Weir L, Bultz BD, Magwood B, et al. Standardized audiotape versus recorded consultation to enhance informed consent to a clinical trial in breast oncology. Psychooncology 2007;16:371–6.

- Hietanen PS, Aro AR, Holli KA, Schreck M, Peura A, Joensuu HT. A short communication course for physicians improves the quality of patient information in a clinical trial. Acta Oncol 2007;46:42–8.

- OECD education at a glance 2012: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2012.

- Bergenmar M, Johansson H, Wilking N. Levels of knowledge and perceived understanding among participants in cancer clinical trials – factors related to the informed consent procedure. Clin Trials 2011;8:77–84.

- Dear RF, Barratt AL, Askie LM, Butow PN, McGeechan K, Crossing S, et al. Impact of a cancer clinical trials web site on discussions about trial participation: A cluster randomized trial. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1912–8.