Abstract

Background. Recent data have suggested that regular aspirin use improves overall and cancer-specific survival in the subset of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients harboring PIK3CA mutations. However, the number of PIK3CA-mutated CRC patients examined in these studies was modest. Our collaborative study aims to validate the association between regular aspirin use and survival in patients with PIK3CA-mutated CRC.

Patients and methods. Patients with PIK3CA-mutated CRC were identified at Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) in the United States and Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) in Australia. Prospective clinicopathological data and survival data were available. At MCC, PIK3CA mutations were identified by targeted exome sequencing using the Illumina GAIIx Next Generation Sequencing platform. At RMH, Sanger sequencing was utilized. Multivariate survival analyses were conducted using Cox logistic regression.

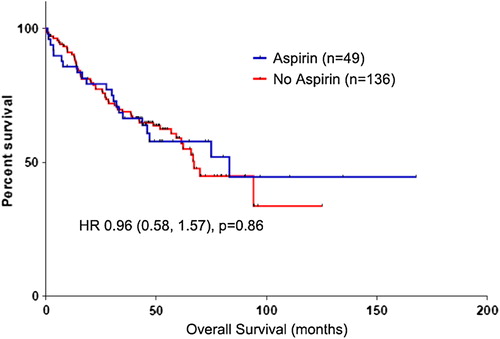

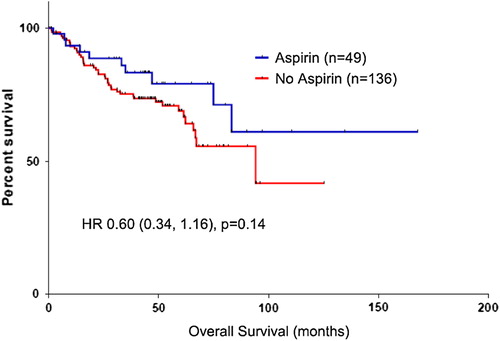

Results. From a cohort of 1487 CRC patients, 185 patients harbored a PIK3CA mutation. Median age of patients with PIK3CA-mutated tumors was 72 years (range: 34–92) and median follow up was 54 months. Forty-nine (26%) patients used aspirin regularly. Regular aspirin use was not associated with improved overall survival (multivariate HR 0.96, p = 0.86). There was a trend towards improved cancer-specific survival (multivariate HR 0.60, p = 0.14), but this was not significant.

Conclusions. Despite examining a large number of patients, we did not confirm that regular aspirin use was associated with statistically significant improvements in survival in PIK3CA-mutated CRC patients. Prospective evaluation of this relationship is warranted.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cause of cancer death worldwide [Citation1]. Over recent years, the evolution of cytotoxic chemotherapy and the addition of effective molecular targeted therapies have led to significant improvements in survival [Citation2–4]. However, toxicity, lack of efficacy, and cost have hindered the development of new agents which could further improve survival [Citation5,Citation6].

Several studies have explored the role of common medications such as HMG CoA reductase inhibitors, cyclooxygenase (COX or PTGS) inhibitors and aspirin as potentially efficacious, safe, lower cost therapeutics in CRC [Citation7,Citation8]. While the cardiovascular toxicities associated with COX inhibitors have slowed their development as anti-cancer treatments [Citation9], studies using aspirin have been very promising. Regular aspirin use reduces incidence of both colorectal adenomas and cancer [Citation10]. A large meta-analysis by Rothwell and colleagues which included over 14 000 CRC patients with close to 20 year follow-up demonstrated that aspirin use resulted in a 24% reduction in CRC incidence and a 35% reduction in CRC mortality [Citation11].

While aspirin's mechanism of action as an anti-cancer agent remains unknown, there are various hypotheses: 1) as an antiplatelet agent, aspirin prevents tumor thrombus formation thereby limiting metastatic potential [Citation12]; 2) as a prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2 or COX2) inhibitor, aspirin blocks downstream prostaglandin synthesis and thus, interrupts its tumor promoting interaction with the Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway [Citation13]. Mutations in PIK3CA are found in approximately 15% of CRC and while they have no established prognostic value [Citation12,Citation14], they are known to deregulate AKT activation and downstream growth factors [Citation15,Citation16], PIK3CA mutations have therefore been evaluated as a potential predictive biomarker for aspirin therapy in CRC.

Liao and colleagues explored this association in a retrospective study that evaluated survival based on aspirin use and PIK3CA mutations. They found improved overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) in aspirin users in PIK3CA-mutated CRC [HR 0.54 (0.31–0.94)] but not in wild type PIK3CA [Citation13]. This study included 161 PIK3CA mutant patients, 66 of whom used aspirin regularly. This finding was reproduced by Domingo and colleagues who studied a clinical trial cohort of stages 2 and 3 CRC patients and demonstrated improved recurrence-free survival (RFS) associated with aspirin use in PIK3CA-mutated CRC [HR 0.11 (0.001–0.832)], but again not in those with wild type PIK3CA [Citation17]. In total 104 patients had PIK3CA mutation and 14 of those used aspirin regularly. However, in a recently published study, Reimers and colleagues did not confirm this association and found no improvement in survival of PIK3CA mutant patients who took aspirin as compared to wild type patients. They included a cohort of 100 PIK3CA mutant patients, 27 of whom took aspirin regularly [Citation18].

While aspirin has relatively low toxicity compared to chemotherapy and targeted agents, it is known to increase the risk of gastrointestinal and cerebral bleeding [Citation19]. Confirmation of PIK3CA mutations as a predictive biomarker will help optimize patient selection and avoid exposure in those unlikely to benefit from aspirin use.

The current study combines data from two large academic institutions and examines a large group of PIK3CA-mutated CRC patients. We undertook this study to confirm the assocation between regular aspirin use and improved survival.

Material and methods

Patient population

This study involved collaboration between Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) in Melbourne, Australia and Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) in Tampa, FL, USA. Patients with CRC harboring a somatic PIK3CA mutation were identified for analysis.

At RMH, a cohort of 1019 consecutive CRC patients diagnosed between 1996 and 2009 were identified using a prospective multisite, multidisciplinary comprehensive CRC database (ACCORD, Biogrid Australia). At MCC and consortium sites, 468 CRC patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2010 were identified as part of a multi-institutional observational study (Total Cancer Care Protocol) [Citation20].

RMH patients had PIK3CA testing by Sanger Sequencing of exons 9 and 20 as previously described [Citation14]. MCC patients had testing done on DNA extracted from fresh frozen tissue. PIK3CA (part of a 1321 gene target set) was captured using a custom Agilent SureSelect design. Next Generation Sequencing using the Illumina GAIIx platform was performed with 50–100X average coverage. The BWA/GATK pipeline identified variants and indels. Normal variants were filtered using the 1000 Genomes Project Database; variants identified with an MAF < 0.01 were retained. PIK3CA mutations at multiple sites were included.

Data collection

Databases at both sites prospectively collected clinicopathological data and survival data. Data regarding regular aspirin use were collected retrospectively through chart review. Aspirin users were defined as those patients with documentation in the medical record of taking at least 75 mg of aspirin daily at the time of CRC diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Survival distributions and median follow-up were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate and multivariate hazard ratios were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Variables selected for multivariate models included aspirin, age, stage, cancer centre and primary site. These calculations were performed using the ‘survival’ library in the R statistical computing environment (version 2.13.2). p-Values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

A total of 185 PIK3CA mutant CRC patients were identified. From 1019 patients at RMH, 112 (11%) had a PIK3CA mutation at exon 9 or 20. At MCC, 73 (16%) of 468 patients had a PIK3CA mutation, of which 40 (9%) were within exons 9 and 20. There were slight differences in the patient populations between RMH and MCC: the RMH cohort was older (median age 74 vs. 69 years, p = 0.039) and had a higher proportion of metastatic disease (28% vs. 18%, p = 0.001) as described in Supplementary Table I (to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990158).

Overall, median follow-up was 54 months and median OS was 70 months. Differences in baseline characteristics between aspirin users and non-users are outlined in . Of the 185 patients, 49 (26%) used aspirin regularly, while 136 (74%) were non-users. The majority of aspirin users (n = 157, 85%) were taking between 81 mg and 100 mg of aspirin each day, with the remainder taking 150 mg (n = 26) or 325 mg (n = 2). Aspirin users were significantly older (median age 74 years vs. 70 years, p = 0.009) and had a significantly higher proportion of left-sided cancers (59% vs. 35%, p = 0.006). There was no difference in stage distribution between aspirin users and non-users.

Table I. Baseline characteristics of patients with PIK3CA-mutated CRC comparing aspirin use to non-use.

Regular aspirin use was not associated with significant improvements in OS in CRC patients in univariate and multivariate analyses (multivariate HR 0.96, p = 0.86; , ). However, there was a trend towards benefit for aspirin use in CSS (multivariate HR 0.60, p = 0.14; , ). Increasing age and stage were associated with significantly poorer OS, with stage also associated with poorer CSS. Left-sided cancers trended towards better OS and CSS, although this was not significant. There was no significant survival difference between MCC and RMH. In addition, the lack of survival advantage associated with regular aspirin use was observed consistently across both centers (Supplementary Table II, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990158).

Table II. Univariate and multivariate overall and cancer-specific survival analyses for patients with PIK3CA mutated CRC.

Similarly, aspirin use did not result in improved OS, CSS or RFS in patients with stage 2 and 3 disease (). In stage 4 disease, there was a trend towards improved OS and CSS with aspirin use in univariate analyses (HR 0.40, p = 0.06; Supplementary Figure 1, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990158).

Table III. Overall, cancer-specific and recurrence-free survival for patients with PIK3CA-mutated CRC – Aspirin use versus non-use (per stage).

A subset analysis of the 152 patients with mutations in exons 9 and 20 was also conducted. In this subgroup, median OS was 70 months and median follow-up 59 months. Findings within this subgroup were consistent with the entire cohort; there was no significant association between aspirin use and improved OS or CSS (Supplementary Tables III–V, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990158).

Discussion

Aspirin has been reported to reduce the incidence of CRC and to improve survival in CRC patients [Citation11]. Due to increased rates of bleeding complications, there has been caution in including aspirin in standard of care guidelines for CRC prevention and survivorship. A predictive biomarker may enhance patient selection for aspirin therapy. In this study, we sought to confirm the previously reported association between PIK3CA mutations and improved survival with regular aspirin use in a large sample of PIK3CA-mutated CRC [Citation13,Citation17]. Our study did not demonstrate a significant association between regular aspirin use and improved OS, CSS or RFS, in PIK3CA-mutated CRC patients.

Our study had some differences from previously published work. Both the Liao and Domingo studies used DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue. Our study used a combination of fresh frozen and paraffin-embedded tissue. While paraffin-embedded tissue may be subject to degradation, it is unlikely to have an effect on sequencing results [Citation21]. The PIK3CA mutation rate for exons 9 and 20 in our population was 10.2%, similar to the 11.6% found in the Domingo study [Citation17]. The Liao study had a higher mutation rate of 16.7% [Citation13].

In our study, 26% of patients used aspirin regularly, compared to 41% in the Liao study and 13% in the Domingo study. Our aspirin use rate is similar to a recent study which reported 28% aspirin use in the community setting [Citation22]. Aspirin users were older in our study, likely reflecting that aspirin is often prescribed for cardiovascular disease (or risk factors) which are more prevalent with increasing age. This was also observed in the Domingo study, but not in the Liao study [Citation13,Citation17]. It is possible that the cohort of health professionals studied by Liao was more health conscious and vigilant with preventative medicine [Citation23], thus explaining the higher proportion of aspirin use and the lack of age difference between users and non-users.

While the Liao study noted a difference in stage at diagnosis, our study did not: Liao reported 41% stage 1 cancer in aspirin users compared to 20% in non-users [Citation13]; our study demonstrates 4% stage 1 in both groups. This discrepancy in stage distribution may reflect higher rates of bowel cancer screening amongst the health conscious health professionals. We did find that left-sided cancers were more common in aspirin users. While this is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated regular aspirin use significantly reduces the incidence of proximal colon cancer but not distal colon cancer [Citation11], a difference in primary tumor site was not observed in either the Liao or Domingo studies [Citation13,Citation17].

Though our cohort was selected for PIK3CA mutants, it arose from an unselected patient population which represents real world patients, and thus differs in some respects from the clinical trial cohort examined in the Domingo study and the health professional cohort examined in the Liao study. Differences in age, co-morbidities, primary tumor site, stage-distribution and possibly tumor biology may be one explanation as to why our study did not confirm the previously reported survival advantage associated with aspirin use in PIK3CA mutant CRC.

Our study is subject to the inherent biases associated with retrospective studies. Aspirin use data was not prospectively collected and duration of aspirin use or compliance was not available; this is a major limitation of our study, as aspirin use documented in the chart at diagnosis may not accurately reflect actual aspirin use leading up to and following diagnosis. Though aspirin use was not associated with improved OS in our patients, there was a trend towards improvement in CSS which suggests that the aspirin users may have had benefit but it was negated by the comorbidities for which they were taking aspirin. Again, this reflects a real world population where comorbidities or even compliance with medication are often significant issues. Another limitation of our study is the lack of data regarding the use of systemic chemotherapy or radiotherapy. In addition, our study included non-exon 9 and 20 PIK3CA mutations, the significance of which remains to be elucidated; however, we have demonstrated that our findings remain consistent even when limited to mutations in exons 9 and 20. We also recognize that the differences in platforms used to identify PIK3CA mutations within this study and compared to previous studies may impact the results. Finally, we did not analyze patients with wild type PIK3CA which was out of the scope of this work. These factors, along with a shorter median follow-up (54 months compared to 61.5 months and 153 months for the Domingo and Liao studies, respectively), may also have contributed to the differences between our findings and those previously reported [Citation13,Citation17]. However, our study population of 185 PIK3CA mutant CRC patients is similar in size to both that of the Liao study (n = 161) and the Domingo study (n = 104) and our cohort represents a generalizable population with CRC patients from two different continents and from a wide range of academic and community treatment settings.

Aspirin has a role in the treatment of CRC that has not yet been fully defined. It has been suggested that PIK3CA mutation location and interaction of PIK3CA and KRAS mutations could affect outcomes [Citation24]. In addition, the role of aspirin use before or after the diagnosis of CRC might affect the genetics of the disease [Citation25]. As next generation sequencing becomes more widespread and larger patient cohorts are assembled, future work can better define the role of aspirin in personalized CRC care.

Conclusions

Our study was not able to confirm the previously reported OS or CSS benefits associated with aspirin use in PIK3CA mutant CRC patients across all stages, despite studying a similarly sized population to previous publications. However, aspirin remains an exciting therapy for future investigation both because of cost and its relatively benign side effect profile. In order to determine the validity of PIK3CA as a predictive biomarker for aspirin use as an anti-cancer agent, a prospective randomized study design is warranted.

Supplementary material available online

Supplementary Figure 1 and Table I–V to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990158

ionc_a_990158_sm2349.pdf

Download PDF (94.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the Victorian Cancer BioBank for patient specimens (Australia). We also thank Total Cancer Care® enabled, in part, by the generous support of the DeBartolo Family, and we thank the many patients who so graciously provided data and tissue to the Total Cancer Care Consortium (United States). This work was originally presented at the 2014 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium. This work was supported by funding from Ludwig Cancer Research (to OMS, PG) and a NHMRC R.D. Wright Biomedical Career Development Fellowship (to OMS). This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant P30-CA76292] under the Biostatistics and Cancer Informatics Core Facilities at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Colorectal cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2008 Summary, 2010. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheet.asp. Cited 15th September 2014.

- Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. New Engl J Med 2004;350:2335–42.

- Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, Khayat D, Bleiberg H, Santoro A, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. New Engl J Med 2004;351:337–45.

- Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, Van Cutsem E, Siena S, Freeman DJ, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1626–34.

- Karaca-Mandic P, McCullough JS, Siddiqui MA, Van Houten H, Shah ND. Impact of new drugs and biologics on colorectal cancer treatment and costs. J Oncol Pract 2011;7:e30s–7s.

- Tran B, Keating CL, Ananda SS, Kosmider S, Jones I, Croxford M, et al. Preliminary analysis of the cost-effectiveness of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: Demonstrating the potential value of comprehensive real world data. Intern Med J 2012;42:794–800.

- Bardou M, Barkun A, Martel M. Effect of statin therapy on colorectal cancer. Gut 2010;59:1572–85.

- Meyerhardt JA, editor. Beyond standard adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: Role of nonstandard interventions. Semin Oncol 2011: NIH Public Access.

- Kerr DJ, Dunn JA, Langman MJ, Smith JL, Midgley RS, Stanley A, et al. Rofecoxib and cardiovascular adverse events in adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer. New Engl J Med 2007;357:360–9.

- Cole BF, Logan RF, Halabi S, Benamouzig R, Sandler RS, Grainge MJ, et al. Aspirin for the chemoprevention of colorectal adenomas: Meta-analysis of the randomized trials. J Natl Cancer Instit 2009;101:256–66.

- Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Elwin C-E, Norrving B, Algra A, Warlow CP, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: 20-year follow-up of five randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376:1741–50.

- Ogino S, Lochhead P, Giovannucci E, Meyerhardt J, Fuchs C, Chan A. Discovery of colorectal cancer PIK3CA mutation as potential predictive biomarker: Power and promise of molecular pathological epidemiology. Oncogene 2014; 33:2949–55.

- Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. New Engl J Med 2012;367: 1596–606.

- Day FL, Jorissen RN, Lipton L, Mouradov D, Sakthianandeswaren A, Christie M, et al. PIK3CA and PTEN gene and exon mutation-specific clinicopathologic and molecular associations in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:3285–96.

- Ikenoue T, Kanai F, Hikiba Y, Obata T, Tanaka Y, Imamura J, et al. Functional analysis of PIK3CA gene mutations in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 2005;65:4562–7.

- Rosty C, Young JP, Walsh MD, Clendenning M, Sanderson K, Walters RJ, et al. PIK3CA activating mutation in colorectal carcinoma: Associations with molecular features and survival. PloS One 2013;8:e65479.

- Domingo E, Church DN, Sieber O, Ramamoorthy R, Yanagisawa Y, Johnstone E, et al. Evaluation of PIK3CA mutation as a predictor of benefit from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:4297–305.

- Reimers MS, Bastiaannet E, Langley RE, van Eijk R, van Vlierberghe RL, Lemmens VE, et al. Expression of HLA class I antigen, aspirin use, and survival after a diagnosis of colon cancer. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:732–9.

- De Berardis G, Lucisano G, D’Ettorre A, Pellegrini F, Lepore V, Tognoni G, et al. Association of aspirin use with major bleeding in patients with and without diabetes. JAMA 2012;307:2286–94.

- Fenstermacher DA, Wenham RM, Rollison DE, Dalton WS. Implementing personalized medicine in a cancer center. Cancer J (Sudbury, Mass) 2011;17:528.

- Tran B, Dancey JE, Kamel-Reid S, McPherson JD, Bedard PL, Brown AM, et al. Cancer genomics: Technology, discovery, and translation. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:647–60.

- Roth GA, Gillespie CW, Mokdad AA, Shen DD, Fleming DW, Stergachis A, et al. Aspirin use and knowledge in the community: A population-and health facility based survey for measuring local health system performance. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014;14:16.

- Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Willett WC. Aspirin use and the risk for colorectal cancer and adenoma in male health professionals. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:241–6.

- Viudez A, Hernandez I, Vera R, de Navarra CH, Liao X, Lochhead P, et al. Aspirin, PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med 2013;368:289.

- Pasche B. Differential effects of aspirin before and after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. JAMA 2013;309:2598–9.