Abstract

Background Systematic assessments of cancer patients’ rehabilitation needs are a prerequisite for devising appropriate survivorship programs. Little is known about the fit between needs assessment outlined in national rehabilitation policies and clinical practice. This study aimed to explore clinical practices related to identification and documentation of rehabilitation needs among patients with colorectal cancer at Danish hospitals.

Material and methods A retrospective clinical audit was conducted utilizing data from patient files randomly selected at surgical and oncology hospital departments treating colorectal cancer patients. Forty patients were included, 10 from each department. Semi-structured interviews were carried out among clinical nurse specialists. Audit data was analyzed using descriptive statistics, qualitative data using thematic analysis.

Results Documentation of physical, psychological and social rehabilitation needs initially and at end of treatment was evident in 10% (n = 2) of surgical patient trajectories and 35% (n = 7) of oncology trajectories. Physical rehabilitation needs were documented among 90% (n = 36) of all patients. Referral to municipal rehabilitation services was documented among 5% (n = 2) of all patients. Assessments at surgical departments were shaped by the inherent continuous assessment of rehabilitation needs within standardized fast-track colorectal cancer surgery. In contrast, the implementation of locally developed assessment tools inspired by the distress thermometer (DT) in oncology departments was challenged by a lack of competencies and funding, impeding integration of data into patient files.

Conclusion Consensus must be reached on how to ensure more systematic, comprehensive assessments of rehabilitation needs throughout clinical cancer care. Fast-track surgery ensures systematic documentation of physical needs, but the lack of inclusion of data collected by the DT in oncological departments questions the efficacy of assessment tools and points to a need for distinguishing between surgical and oncological settings in national rehabilitation policies.

The rising number of cancer survivors worldwide (32.6 million) in recent years has resulted in the development of national cancer survivorship programs in Europe and America [Citation1,Citation2]. However, there is an unmet international need for united strategic cancer survivorship programs concentrating on evidence-based interventions supporting the recovery of cancer patients. Due to the significant level of political interest in cancer rehabilitation, national policies have now been introduced to ensure recovery of lost functional ability and quality of life following cancer therapy [Citation3]. In Denmark the national policies from 2012 include guidelines for continually identifying and assessing the physical, psychological and social rehabilitation needs of cancer patients throughout their treatment program [Citation4], which calls for the implementation of validated assessment tools to analyze rehabilitation needs in clinical practice [Citation5,Citation6]. The use of a systematic procedure for assessing the rehabilitation needs of cancer patients in clinical practice is still in its infancy in the US and various European countries [Citation7]. However, despite interest on the part of health authorities and recommendations to implement a system of continual appraisal of needs, we do not know today whether these recommendations have been implemented in clinical practice in individual surgical and oncology departments. We believe we can find out more by analyzing the documentation from patient records. A systematic literature search did not reveal any other studies which have used a record audit to tackle this issue in clinical practice. This study aims to explore clinical practices related to identification and documentation of rehabilitation needs by means of clinical audit among patients with colorectal cancer at randomly selected surgical and oncology hospitals departments in Denmark.

Material and methods

This study is part of a larger mixed-methods cross-sectional study investigating how cancer rehabilitation is currently organized and practiced in Denmark [Citation8]. In the sub-study we used the case of colorectal cancer, which is estimated to be the second most common cancer diagnosis in Europe [Citation2]. The introduction of fast-track surgical programs has been shown to improve recovery and reduce hospital stay, readmission and morbidity for colorectal cancer patients [Citation9,Citation10]. However, colorectal cancer mainly occurs among older adults, often with various comorbidities, and accounts for a large understudied group of patients [Citation2,Citation11]. We carried out a retrospective clinical audit and qualitative interviews with clinical nursing specialists to examine how the rehabilitation needs of colorectal cancer patients are documented. The 19 surgical and 12 oncology departments in Denmark which treat patients with colorectal cancer were assigned a number. Two surgical and two oncology departments geographically representing eastern and western Denmark were then randomly selected. We subsequently wrote or talked to the consultants in the departments about the aim of the clinical audit and the qualitative interviews. All four departments agreed to participate in the study.

Clinical audit methodology

The clinical audit took place in 2014 from the end of May to early July at four departments, which were asked to retrieve complete patient files on the first 10 colorectal cancer patients enrolled for treatment from 1 September 2013 who had also completed a full course of treatment or who were in intermittent chemotherapy when the audit was initiated. The date was based on the prolonged treatment modules within oncology and to ensure that complete oncology trajectories could be examined for at least seven months. The audit was carried out in accordance with the Principles for Best Practice in Clinical Audit published by the National Institute for Care Excellence [Citation12]. Process criteria were developed in a data abstraction form on the assessment of patients’ rehabilitation needs during the cancer treatment trajectory. The criteria covered physical (loss of physical function), psychological (e.g. recorded signs of anxiety and depression) and social (socio-economic status and living conditions) functional ability in patients as well as referrals to municipal rehabilitation services. The criteria were classified into dichotomous statements (“yes” or “no”). A rehabilitation assessment was considered to have been carried out if documented in the patient file. Full cancer treatment trajectories were systematically reviewed by two reviewers from the research team in cooperation with the coordinating clinical nurse specialist in cancer rehabilitation selected by the hospital management in each department. In addition, a chief physician at one department participated during the clinical audit. The coordinating clinical nurse rehabilitation specialists were involved to ensure that data from patient records could be accessed, that the collected data was valid and consistent and that the data material was appropriately interpreted to provide reliable feedback to the hospital staff. Researchers were not given access to any personal identification on the patients. Ratings were compared and reviewers came to a consensus for all of the treatment trajectories. The clinical audit was analyzed using descriptive statistics in Excel.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews lasting 40–50 minutes were conducted to contextualize findings from the clinical audit. Themes included clinicians’ knowledge of their responsibilities related to cancer rehabilitation, their interpretation of rehabilitation and the organization of rehabilitation, including obstacles. The interviews were conducted with the included coordinating clinical nurse specialists following the 10 audited patient files. Interviews was audiotaped, transcribed and then analyzed using thematic analysis.

Ethical considerations

According to official Danish research guidelines, no approval from ethical committees is required for audits and qualitative studies. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (file no. 2013-41-1478). All patient records were reviewed at the respective departments. Data have been securely stored and will be deleted when the study concludes.

Results

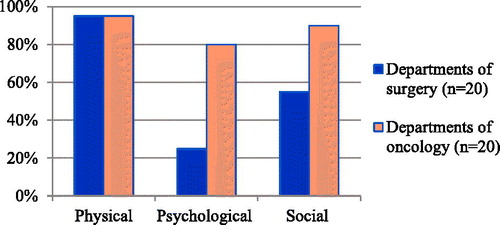

shows the patient demography and the average hospital stay for the 40 surgical and oncology treatment trajectories. All of the patients (n = 40) were undergoing fast-track surgery. In 10% (n = 2) of the surgical and 35% (n = 7) of the oncology treatment trajectories there was a documented analysis of the patients’ physical, psychological and social functional ability both at the start and end of treatment ().

Table 1. Distribution of findings from retrospective clinical journal audit of n = 40 patients with colorectal cancer from four randomly selected hospital departments of surgery (n = 20) and oncology (n = 20). Geographically divided into east and west Denmark.

Table 2. Selected interview quotes illustrating main themes divided between surgical and oncological hospital departments.

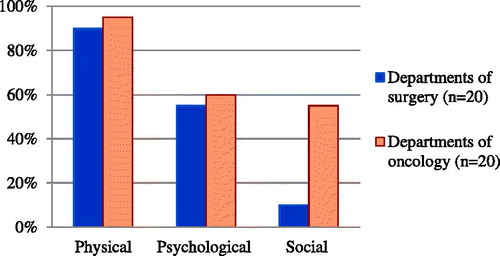

The surgical departments systematically documented the patients’ pre- and post-operative physical functional ability in a standardized procedure that is part of the fast-track surgery concept. The patients’ physical functional ability was documented at the start of treatment in 90% (n = 18) of cases and at the end of treatment in 95% (n = 19) of cases. The patients’ psychological and social functional ability was assessed and documented to a lesser extent ( and ). We found that the patients were instructed in how to monitor themselves (e.g. pain management and nutrition) when they were discharged and they were offered the possibility of telephone support if required, as a part of the fast-track concept. In 25% (n = 5) of the surgical treatment programs, referral to specialized rehabilitation within the hospital regime was documented, such as follow-up measures in the ostomy outpatient clinic, expert dietary advice etc. (). In the post-operative program the hospitals talked to patients in follow-up interviews 10 and 30 days after surgery. We did not observe any systematic evaluation of patients’ rehabilitation needs in their records during these interviews. In the oncology departments there did not appear to be any systematic assessment of the patients’ functional ability in their records. The patients’ physical functional ability was documented at the start of treatment in 95% (n = 19) of cases and at the end of treatment in 95% (n = 19) of cases. Correspondingly the patients’ psychological and social functional ability was often documented initially but to a lesser degree at the end of the treatment programs ( and ). In the oncology departments there were plans to implement a self-developed instrument inspired by distress thermometer (DT) to assess the patients’ rehabilitation needs. In the case of oncology treatment trajectories there was a documented referral to a specialized rehabilitation program within the hospital system () in 40% (n = 8) of cases at the start of treatment and in 70% (n = 14) of cases at the end of treatment. None of the departments did a systematic assessment of rehabilitation needs during the discharge interview.

Figure 1. Whether clinician documented patient’s physical, psychological and social functioning during initial course of treatment (n = 40).

Figure 2. Whether clinician documented patient’s physical, psychological and social functioning at end of a treatment (n = 40).

The audit showed that in the case of 5% (n = 2) of the surgical and oncology treatment trajectories, there was a referral to local municipality rehabilitation services ().

Qualitative findings

The main topics are presented below with details of the findings from the clinical audit. Selected quotations are presented in below.

Varying knowledge of responsibilities in the national rehabilitation policies

The staff in the surgical departments had a lack of knowledge about the national rehabilitation policies. The clinical nurse specialists also stated that the program would not have led to changes in their daily work. In the oncology departments the clinical nurse specialists were aware of the existence of the national rehabilitation policies but tasks had not yet been incorporated into their daily work.

Rehabilitation as an informal part of nurses’ duties

Formal responsibility for implementation of the national rehabilitation policy guidelines was placed with the departments’ consultants, who in all four departments had delegated responsibility to the nursing staff. The nursing staff felt it was natural for them to be responsible for rehabilitation measures in the department and expressed good will and interest in the matter.

Different surgical and oncology interpretations of rehabilitation

Rehabilitation was approached by the surgical departments in terms of preserving physical functional ability. As the audit showed, they focused primarily on ensuring that the patients regained their habitual physical functional ability and on preventing surgical complications. In the oncology departments the clinical nurse specialists had a more holistic approach to rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation integrated into the fast-track concept versus trials using DT

The clinical nurse specialists in the surgical departments expressed professional pride about the fast-track concept, which allowed them to use standardized care schedules to systematically assess and document the patients’ functional ability on a daily basis while hospitalized for surgery. The results from the clinical audit underpin this. Rehabilitation and early mobilization were an integral and standard element of the fast-track concept. The oncology departments were inspired by the internationally validated DT as a screening tool for assessing the patients’ rehabilitation needs. The coordinating clinical nurse specialists said they were pleased with DT, as it identified physical and psycho-social aspects of the cancer patients’ life situation. They explained that DT was seen as being part of the patients’ own personal regime. Thus, the DT was not integrated into existing patient-related databases, which is crucial for knowledge sharing across the sectors.

Time, money and competence: Factors hindering implementation of the DT in clinical practice

The coordinating clinical nurse specialists in the oncology departments expressed doubts about the value of DT in clinical practice when it came to meeting with the patients. They felt that lack of money and time (maximum 15 minutes systematic assessment of rehabilitation needs) and a lack of information about the rehabilitation facilities offered by the local authorities were impediments to holding rehabilitation interviews.

Insufficient need for local municipality rehabilitation services

According to the coordinating clinical nurse specialists in the surgical departments, the patients frequently regained their habitual functional ability during the surgical fast-track concept. The clinical nurse specialists said that the patients seldom expressed a need for a physical rehabilitation plan when they were discharged from hospital.

Lack of information about rehabilitation services offered to cancer patients by the local municipalities

Both the surgical and oncology departments agreed that they felt inadequately informed about local municipality rehabilitation services and their effects, which is also mirrored in the clinical audit.

Discussion

This study is part of a cross-sectional study of the organization of cancer rehabilitation in Denmark, with emphasis on assessment of the patients’ rehabilitation needs in different phases of the treatment. No examples of national or international studies have been found that have used a clinical audit to examine the documentation of the rehabilitation needs of patients undergoing surgical or oncology treatment.

The study, carried out among responsible clinical nurse specialists, revealed that they had limited knowledge of the national rehabilitation policies, even of the tasks with which the departments were entrusted. The clinical audit showed that none of the four surgical or oncology departments undertook systematic identification and/or documentation of physical, psychological or social rehabilitation needs. Furthermore, the audit identified differences in the way the surgical and oncology departments managed rehabilitation measures.

‘Fast-track’ – a multimodal rehabilitation program

In the surgical departments the documentation of rehabilitation needs was covered by the well established fast-track concept, where physical functional ability is documented and standardized physical rehabilitation is incorporated into the treatment protocol. When examining the 20 patient cause of treatment, we did not identify any need for further surgical treatment (operative complications, serious adverse events) in the first month after discharge. The findings underpin the importance of early surgical rehabilitation embedded in the surgical peri- and post-operative fast-track concept [Citation13]. Within colorectal surgery, research in evidence-based fast-track regimes has revealed well documented effects internationally with regard to rapid recovery and reduced hospitalization [Citation14–16]. The fast-track concept has gained wide acceptance internationally and is seen today as a standardized multimodal surgical rehabilitation program [Citation17].

Our findings show the challenges arising from changes to clinical practice, especially when it comes to the implementation of centrally formulated guidelines at practice level. The national policies on identification of rehabilitation needs can be promoted by being integrated into existing practice and thus do not pose a challenge to the well established and evidence-based nature of the fast-track concept, Implementation of the policies is more challenging when these are to be incorporated into clinical practice with less well established structures and when evidence of the relevance and effect of the recommendations is less obvious. Special organizational measures are required to further the implementation of the different facets of rehabilitation needs, such as communication, documentation of evidence and structural changes at practice level [Citation18,Citation19].

It was apparent from the interviews with the responsible clinical specialists that none of the surgical departments were intending to introduce a tool for assessing patients’ rehabilitation needs. The surgical departments thus saw their primary task as being to reduce surgical complications and to ensure the patients’ habitual functional level. The study further showed that none of the surgical departments had carried out any systematic assessments of patients’ rehabilitation needs at checkups in the month after discharge from hospital. Patients entering curative treatment were referred to their general practitioner for subsequent follow-up. These findings indicate that the surgical departments fulfill their cancer rehabilitation duties through implementation of the standardized fast-track procedures.

Lack of consensus on the procedure for assessing rehabilitation needs

The oncology departments were less clear about what procedures they would use to identify the rehabilitation needs of cancer patients. The clinical nurse specialists had taken on the responsibility by testing locally developed procedures inspired by the internationally validated DT [Citation20]. The findings indicate that there is not yet a national consensus across hospital departments in Denmark on procedures for assessing rehabilitation needs. Current literature also reflects the fact that rehabilitation measures for cancer patients are organized in very different ways internationally [Citation3]. Stubblefield et al. (2013) showed that systematic cancer rehabilitation programs have not yet manifested themselves in the US. For the most part, oncology rehabilitation during treatment programs is delivered by private treatment providers and the communication of cancer rehabilitation services is limited [Citation21]. In several European countries cancer rehabilitation is included in national cancer plans [Citation3]. However, the identification and documentation of rehabilitation needs is not yet routinely established as a standard part of clinical practice and implementation varies significantly due to different health systems and financial resources [Citation21]. The Netherlands, Britain, Norway and Sweden are working towards systematic cancer rehabilitation programs under national guidelines across hospitals and the primary sector [Citation7]. In Germany cancer rehabilitation has in recent decades been a fully integrated part of the social security system, with all patients being offered a specialized, three-week, across-the-board rehabilitation program during hospitalization on the basis of an assessment of functional ability and rehabilitation needs [Citation3,Citation7]. Despite initiatives within cancer rehabilitation across Europe, there is not yet a consensus on optimum clinical guidelines for assessing cancer patients’ rehabilitation needs during treatment programs [Citation22,Citation23].

DT not integrated in from patients’ treatment protocol

The findings showed that completed questionnaires on DT were not saved in patient records in the oncology departments, but were seen as the patients’ personal material. DT was thus not an integral element of patient-related databases and there was limited scope for subsequent follow-up or evaluation of patient treatment programs across the sectors. Additionally, the findings revealed a lack of strategy for a common database for registering the effects of the assessments of rehabilitation needs across the sectors and regions that had been set in motion. This finding is supported by Richardson et al. (2007) in a British review showing that there is a dearth of evaluations of the viability of measurement tools, professional clinical applicability and the effects on patient outcomes [Citation24]. Rehabilitation of cancer patients should be set up to include evaluation and organized on an evidence base.

The study revealed from the interviews with the responsible clinical specialists that there was a lack of resources for the implementation of DT as a uniform assessment tool in the oncology departments, a finding which echoes previous studies looking at the extent to which DT as a tool is able to pinpoint the rehabilitation needs of cancer patients [Citation25]. The interview findings illuminated that within all departments there was limited knowledge and a limited number of referrals to the district rehabilitation programs. According to a review by Mitchell et al. (2013) of the screening for distress it was found that one of the barriers to successful implementation of an assessment tool for determining rehabilitation needs in the clinical setting is the lack of knowledge about appropriate rehabilitation services. An assessment tool – DT – will not benefit patient outcomes if hospital staff do not have the necessary competence to identify rehabilitation needs and refer to relevant rehabilitation services [Citation23]. The results of this study thus support earlier findings pointing to an increased need for more formalized, national competence development for clinical nurses so they can carry out the task and issue referrals to relevant and meaningful rehabilitation services.

Methodological considerations

The clinical audit provides an insight into current hospital practice in Denmark with respect to assessment of rehabilitation needs and referral to rehabilitation services for patients with colorectal cancer. Using a mixed-methods approach the study could help to identify “gaps” between the national policies for rehabilitation and concrete clinical practice. The small sample size of the study limits the general applicability of the results. However the clinical audit was carried out on patient records selected randomly from four departments that had been randomly selected among Danish surgical and oncology departments and thus chosen to be part of the study. We do, however, expect other surgical and oncology departments to face similar challenges. To understand the findings from the oncology departments it is important to be aware that a retrospective cross-sectional study design was used that identified the documentation when testing DT in clinical practice. The strength of the study lies in the fact that qualitative data was collected via the respective clinical nurse specialists in charge of rehabilitation measures, in order to gain an insight into the process surrounding the registering of rehabilitation needs in the records, which support to contextualize our findings. Furthermore, the clinical audit was conducted in close cooperation with the responsible physician and nurse specialist to ensure that the context for the data can be adequately interpreted

Conclusion

Coherent treatment programs and their anticipated effect on the patients’ quality of life are contingent on a systematic evaluation of cancer patients’ rehabilitation needs within hospital practice. In this study a record audit was carried out together with interviews at surgical and oncology departments treating patients with colorectal cancer, with the aim of describing how widely the identification of cancer patients’ rehabilitation needs is established in clinical practice as an integrated systematic procedure. The study found that clinical specialists working within rehabilitation have limited knowledge about the national rehabilitation policies and that there is a lack of systematic identification and documentation of physical, psychological as well as social rehabilitation needs. The documentation of rehabilitation needs was part of the patients’ treatment protocol within the standardized surgical fast-track concept. Despite intentions to use DT according to instructions in the oncology departments, data was not incorporated into existing patient-related databases as an integral element. A lack of competence, financial means and appropriate referral to rehabilitation services call into question the efficacy of assessment tools. National rehabilitation policies need to differentiate between the surgical and oncology setting. Consensus is needed on more systematic and comprehensive assessments of rehabilitation needs throughout clinical cancer care for colorectal cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the departments for their contributions. The study was supported by grants from The Center for Integrated Rehabilitation of Cancer patients (CIRE), which was established and is supported by the Danish Cancer Society and the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Rowland JH, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Loge JH, Hjorth L, Glaser A, et al. Cancer survivorship research in Europe and the United States: where have we been, where are we going, and what can we learn from each other? Cancer 2013;119 (Suppl 11):2094–108.

- Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Int Agency Res Cancer 2013;49:1374–403.

- Mccabe MS, Faithfull S, Makin W, Wengstrom Y. Survivorship programs and care planning. Cancer 2013;119 (Suppl 11):2179–86.

- National Board of Health. 2012. Forløbsprogram for rehabilitering og palliation i forbindelse med kræft - del af samlet forløbsprogram for kræft 2012. [Care programme for rehabilitation and palliation in cancer—part of the total care programme for cancer 2012]. Copenhagen.

- Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1160–77.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: distress management. (ed 3) Fort Washington PA. NCCN 2012.

- Hellbom M, Bergelt C, Bergenmar M, Gijsen B, Loge JH, Rautalahti M, et al. Cancer rehabilitation: A Nordic and European perspective. Acta Oncol 2011;50:179–86.

- Kristiansen M, Adamsen L, Hendriksen C. Readiness for cancer rehabilitation in Denmark: protocol for a cross-sectional mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003775.

- Kehlet H, Slim K. The future of fast-track surgery. Br J Surg 2012;99:1025–6.

- Kehlet H, Harling H. Length of stay after laparoscopic colonic surgery – an 11-year nationwide Danish survey. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:1118–20.

- de Vries E, Soerjomataram I, Lemmens VE, Coebergh JW, Barendregt JJ, Oenema A, et al. Lifestyle changes and reduction of colon cancer incidence in Europe: A scenario study of physical activity promotion and weight reduction. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2605–16.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Principles for best practice in clinical audit. Abingdon, Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd Abingdon, Oxon, 2002.

- Jakobsen DH, Rud K, Kehlet H, Egerod I. Standardising fast-track surgical nursing care in Denmark. Br J Nurs 2014;23:471–6.

- Zhao JH, Sun JX, Gao P, Chen XW, Song YX, Huang XZ, et al. Fast-track surgery versus traditional perioperative care in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2014;14:607.

- Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg 2008;248:189–98.

- Jakobsen DH, Sonne E, Andreasen J, Kehlet H. Convalescence after colonic surgery with fast-track vs conventional care. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:683–7.

- Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to postoperative recovery. Curr Opin Crit Care 2009;15:355–8.

- Alfano CM, Smith T, de Moor JS, Glasgow RE, Khoury MJ, Hawkins NA, et al. An action plan for translating cancer survivorship research into care. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:1–9.

- Pollack LA, Greer GE, Rowland JH, Miller A, Doneski D, Coughlin SS, et al. Cancer survivorship: a new challenge in comprehensive cancer control. Cancer Causes Control 2005;16 (Suppl 1):51–9.

- Donovan KA, Grassi L, Mcginty HL, Jacobsen PB. Validation of the distress thermometer worldwide: state of the science. Psychooncology 2014;23:241–50.

- Stubblefield MD, Hubbard G, Cheville A, Koch U, Schmitz KH, Dalton SO. Current perspectives and emerging issues on cancer rehabilitation. Cancer 2013;119 (Suppl 11):2170–8.

- Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, Buchmann LO, Compas B, Deshields TL, et al. Distress management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11:190–209.

- Mitchell AJ. Screening for cancer-related distress: when is implementation successful and when is it unsuccessful? Acta Oncol 2013;52:216–24.

- Richardson A, Medina J, Brown V, Sitzia J. Patients’ needs assessment in cancer care: a review of assessment tools. Support Care Cancer 2007;15:1125–44.

- Hollingworth W, Metcalfe C, Mancero S, Harris S, Campbell R, Biddle L, et al. Are needs assessments cost effective in reducing distress among patients with cancer? A randomized controlled trial using the Distress Thermometer and Problem List. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3631–8.