Abstract

Background Recent epidemiologic data show that Denmark has considerably poorer survival from common cancers than Sweden. This may be related to a lower awareness of cancer symptoms and longer patient intervals in Denmark than in Sweden. The aims of this study were to: 1) compare population awareness of three possible symptoms of cancer (unexplained lump or swelling, unexplained bleeding and persistent cough or hoarseness); 2) compare anticipated patient interval when noticing any breast changes, rectal bleeding and persistent cough; and 3) examine whether potential differences were noticeable in particular age groups or at particular levels of education in a Danish and Swedish population sample.

Method Data were derived from Module 2 of the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership. Telephone interviews using the Awareness and Beliefs about Cancer measure were conducted in 2011 among 3000 adults in Denmark and 3070 adults in Sweden.

Results Danish respondents reported a higher awareness of two of three symptoms (i.e. unexplained lump or swelling and persistent cough or hoarseness) and a shorter anticipated patient interval for two of three symptoms studied (i.e. any breast changes and rectal bleeding) than Swedish respondents. Differences in symptom awareness and anticipated patient interval between these countries were most pronounced in highly educated respondents.

Conclusion Somewhat paradoxically, the highest awareness of symptoms of cancer and the shortest anticipated patient intervals were found in Denmark, where cancer survival is lower than in Sweden. Thus, it appears that these differences in symptom awareness and anticipated patient interval do not help explain the cancer survival disparity between Denmark and Sweden.

Large variations in survival from common cancers are seen between Denmark and Sweden, two Nordic welfare states with many socio-economic and healthcare system similarities [Citation1].

Thus, women in Sweden diagnosed with breast, colon and lung cancer during 2009–2011 had 2, 9 and 10 percentage point advantages in one-year relative survival, respectively, compared with women in Denmark. A similar difference was observed among men for colon and lung cancer [Citation2].

It has been suggested that the poorer survival from cancer in Denmark than in Sweden may be due to more advanced disease stages at diagnosis [Citation1,Citation3], which might be explained, in part, by longer patient intervals [Citation1,Citation4] (i.e. the time from the first symptom is experienced until healthcare is sought [Citation5]). A body of research has made efforts to identify factors associated with longer patient intervals [Citation6–9]. In a comprehensive review of several cancer types, Macleod et al. [Citation9] found that not recognizing the seriousness of a symptom was the main patient-mediated factor associated with a long patient interval. One reason for the lack of recognition of the serious nature of symptoms may be low awareness about which symptoms may be indicative of cancer [Citation9,Citation10]. However, only a few comparative studies [Citation11,Citation12] have analyzed whether awareness differs between settings with different cancer survival rates. The aim of the present study was therefore to compare awareness of three symptoms of cancer (unexplained lump or swelling, unexplained bleeding and persistent cough or hoarseness) and to compare anticipated patient interval when noticing any breast changes, rectal bleeding and persistent cough between a Danish and Swedish population sample. A further aim was to examine whether potential differences between the countries were especially prominent in specific age groups or at particular levels of education. We hypothesized that in line with the lower survival rates in Denmark, the Danish population sample would show a lower symptom awareness and have a longer anticipated patient interval than the Swedish sample.

Methods

Study population and data collection

Data were collected as part of Module 2 of the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP). The ICBP examines international variations in cancer survival and possible reasons for these variations in Australia, Canada, England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Norway, Sweden and Denmark. Module 2 was designed to specifically explore differences in population awareness and beliefs about cancer [Citation13].

In Denmark and Sweden, the target was to include 1000 respondents 30–49 years of age and 2000 respondents aged ≥50 from each country. In Denmark, a total of 20 000 residents 30–49 years of age and 40 000 residents aged 50 and older were randomly selected from the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS) [Citation14]. In Sweden, a sample of 8000 residents in the age group 30–49 and 15 000 residents aged 50 and older from the Uppsala-Örebro and the Stockholm-Gotland healthcare regions were randomly selected from the Swedish Population and Address Register (SPAR) [Citation15]. In both countries, these continuously updated registers of all residents include a personal identification number and variables, such as name, address, gender, civil status, date and place of birth. Names and/or addresses as listed in the CRS and SPAR were then matched with their landline and/or mobile phone numbers by national market research and consulting firms (NN Markedsdata in Denmark and Infodata in Sweden).

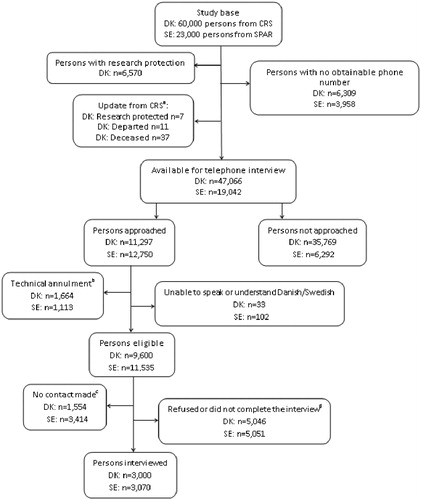

The survey was conducted from 31 May to 4 July 2011 in Denmark and from 15 August to 30 September 2011 in Sweden. Telephone interviews were carried out by trained native-speaking interviewers from a research company, Ipsos MORI, using the Awareness and Beliefs about Cancer (ABC) measure [Citation16]. Each interview took approximately 20 minutes. Up to seven attempts were made to reach each person with calls being made at different times and different days. Interviews were not performed if the respondents were unable to speak or understand Danish or Swedish. shows the data collection process used to obtain the target sample size. As can be seen from the figure, about one third of those who were available for telephone interview were approached by the interviewers from Ipsos MORI. The persons approached were randomly selected, thus all persons available for telephone interviews had an equal chance of selection.

Figure 1. The data collection process for Denmark and Sweden. (a) Before start of data collection in Denmark, it was checked whether the persons: 1) had a newly established research protection status; 2) had emigrated from Denmark; or 3) had passed away. (b) Include business/fax number, incomplete/unobtainable number, barred and wrong number. (c) Include not available during data collection period, could not be contacted after seven attempts and the persons answering the phone did not want to speak to the interviewer. (d) Include refused to take part (before or after it was known whether or not it was the person eligible for study participation), stopped the interview, the person eligible for study participation asked to called back at a later date, but could not be contacted again and the person stated that he/she was not in the age group anyway.

Survey measure

The development and validation of the ABC measure is described in detail elsewhere [Citation16]. Data reported here relate to awareness of cancer symptoms and anticipated patient interval.

Awareness of cancer symptoms was assessed by using the prompt: “I’m now going to list some symptoms that may or may not be warning signs for cancer. For each one, can you tell me whether you think that it could be a warning sign for cancer?” In total, 11 symptoms were listed and rotated randomly to avoid bias being introduced by the ordering of the symptoms.

Anticipated patient interval was assessed by the prompt: “The next questions are about going to the doctor. I’m going to read you a list of signs and symptoms. For each one, please tell me how long it would take you to go to the doctor from the time you first noticed the symptom”. In the ABC measure, four symptoms were listed and rotated randomly.

Dependent variables

For the present analyses, awareness of cancer symptoms was measured by an unexplained lump or swelling, an unexplained bleeding and a persistent cough or hoarseness. Respondents could respond yes or no as to whether they thought the specific symptom could be a warning sign for cancer. There was no set option for don’t know; however, such spontaneous responses as well as did not answer were documented by the interviewers. The categories no, don’t know and did not answer were combined here to indicate lack of awareness.

The anticipated patient interval was measured for any breast changes (in women only), rectal bleeding and a persistent cough. The interviewers categorized the respondents’ answers into one of the following categories: as soon as I noticed, up to 1 week, over 1 up to 2 weeks, over 2 up to 3 weeks, over 3 up to 4 weeks, more than a month, and I would not contact my doctor. Additional response alternatives documented were: I would go to another healthcare professional, I would go to a pharmacist (Sweden only), I would go to a nurse at a primary care center (Sweden only), don’t know and did not answer.

Independent variables

Information on country (Denmark, Sweden), age (30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70 + years) and gender (male, female) of the two populations was obtained from the CRS in Denmark and the SPAR in Sweden. Information on marital status (married/cohabiting; living alone), educational level (low: primary/lower secondary school; middle: upper secondary; and high: bachelor and higher), country of birth [country of current residence (DK/SE); other], experience of cancer themselves and/or in family/friend (yes/no) was obtained from the respondent during the ABC interview.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the Danish and Swedish respondents’ symptom awareness and anticipated patient interval. We estimated the associations between country and lack of awareness for each of the three cancer symptoms using a generalized linear regression model with prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We adjusted for age, gender, marital status, educational level and experience of cancer. Similar analyses were performed to examine the association between country and longer anticipated interval. For this purpose, the response categories were dichotomized into two categories of anticipated patient interval. For persistent cough, the NICE guidelines [Citation17] suggest that the cough should have been present for at least three weeks before it is suggestive of cancer; the categories for persistent cough were therefore set at ≤3 weeks versus >3 weeks. The same clarity is not found in recommendations for any breast changes and rectal bleeding; the patient intervals for these symptoms were categorized as ≤2 weeks versus >2 weeks. For these dichotomizations, the additional response alternatives were coded as missing data (less than 0.4% of the responses).

Lastly, data on symptom awareness and the anticipated patient interval were both stratified by five age strata (30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69 and 70 + years) and by three strata for educational level (low, middle and high) to explore whether potential differences between the countries were especially prominent in specific age groups or at particular levels of education.

Results

Populations

The characteristics of the respondents in Denmark and Sweden are presented in . Compared with Sweden, a higher proportion of the respondents from Denmark were married/cohabiting, born in the country of their current residence and reported experience of cancer. Compared with their Danish counterparts, a higher proportion of respondents from Sweden were in the oldest age groups (i.e. 60–69 and ≥70 years) and reported a high educational level (bachelor and higher). There was no statistically significant difference in gender distribution among respondents from Denmark and Sweden.

Table 1. Socio-economic characteristics of the Danish and Swedish respondents. Sums vary because of missing data.

Awareness of cancer symptoms

The most well known of the three symptoms of cancer was an unexplained lump or swelling, which was recognized by over 90% of the respondents in both countries (). A persistent cough or hoarseness was the least well known symptom in both Denmark and Sweden. The adjusted analyzes show that respondents in Denmark were less likely to lack awareness of the symptoms. For example, the adjusted PR (PRadj.) for Denmark was 0.67 (95% CI 0.60–0.73) for lack of awareness that a persistent cough or hoarseness can be a warning sign for cancer ().

Table 2. Distribution of responses and associations between country and lack of awareness that the symptom can be a warning sign for cancer.

Using Sweden as the reference when stratifying for age, the difference between the Danish and the Swedish samples in terms of lack of awareness was largest for an unexplained lump or swelling, and the difference was statistically significant only in the age group 60–69 [PRadj. for DK: 0.55 (95% CI 0.39–0.77)]. Across educational level, significant differences between the two countries were found for the two highest educational groups. Thus, the PRadj. for DK was 0.75 (95% CI 0.56–0.99) and 0.51 (95% CI 0.33–0.77) for respondents with a middle and a high educational level, respectively (data not shown).

For unexplained bleeding, a significant difference was found between respondents aged 50–59 years [PRadj. for DK: 0.77 (95% CI 0.63–0.95)] and for respondents with a high educational level [PRadj. for DK: 0.83 (95% CI 0.69–0.99)] (data not shown).

Lastly, statistically significant differences across all the age groups were found for lack of awareness of a persistent cough or hoarseness except among the youngest age group (PRadj. ranging from 0.47 to 0.76 for DK). Associations across all educational levels were significant (PRadj. ranging from 0.65 to 0.68 for DK) (data not shown).

To summarize, we found that across age groups, the difference in awareness of cancer symptoms was most pronounced among respondents 50 years or older, and the largest difference in symptom awareness across educational level appeared among highly educated respondents. For all significant associations across age and educational level, respondents from Denmark reported higher symptom awareness than respondents from Sweden.

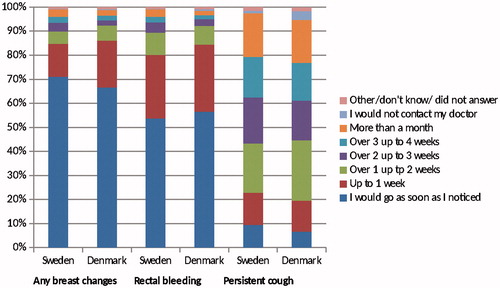

Anticipated patient interval

displays the anticipated patient interval when experiencing breast changes, rectal bleeding and a persistent cough for Denmark and Sweden. The majority of the respondents in both countries reported that when experiencing breast changes or rectal bleeding they would go to the doctor as soon as they noticed the symptom or within one week. Dichotomizing the anticipated patient intervals, we found that Danish respondents were less likely than Swedish respondents to report that they would wait more than two weeks to go to the doctor when they first noticed any breast changes or rectal bleeding (). There was no difference between respondents in Denmark and Sweden concerning the prevalence of reporting a longer anticipated patient interval (>3 weeks) for a persistent cough.

Figure 2. Anticipated patient interval for Sweden and Denmark when experiencing any breast changesa, rectal bleeding and a persistent cough. a Only answered by women.

Table 3. Associations between country and longer anticipated patient interval.

The difference between respondents in Denmark and in Sweden was particularly salient in the youngest age strata (30–39 years of age) with significantly fewer younger respondents from the Danish sample reporting longer anticipated patient interval for both breast changes [PRadj. for DK: 0.42 (95% CI 0.27–0.67)] and rectal bleeding [PRadj. for DK: 0.49 (95% CI 0.33–0.74)] using Sweden as the reference (data not shown). The difference between the two countries was especially prominent in the group with a high educational level with regard to breast change [PRadj.for DK: 0.53 (95% CI 0.36–0.77)] and rectal bleeding [PRadj.for DK: 0.65 (95% CI 0.50–0.85)]. For persistent cough, no statistically significant differences across age groups or educational levels were found.

Thus, again, we found that for all significant associations across age and educational level, respondents from Denmark reported shorter anticipated intervals than respondents from Sweden. Furthermore, the differences between the two countries were especially prominent in the youngest age group and among the respondents with the highest educational level.

Discussion

Main findings

Contrary to our hypotheses, we found that respondents from Denmark reported higher symptom awareness for two of the three symptoms investigated (i.e. unexplained lump or swelling and persistent cough or hoarseness) and shorter anticipated patient intervals for two of three symptoms studied (i.e. any breast changes and rectal bleeding) than respondents in Sweden. Overall, we observed a trend that the largest difference in symptom awareness and anticipated patient interval between the two countries was found among respondents with high educational level.

These data suggest that self-reported differences in symptom awareness and anticipated patient interval related to breast, colon and lung cancer do not help explain disparities in survival from these cancer types between Denmark and Sweden. Nevertheless, it is interesting that the higher cancer symptom awareness and lower anticipated patient interval among respondents from Denmark was particularly prominent among highly educated respondents who also constitute a group with relatively high cancer survival in Denmark [Citation18].

Other potential factors that have been suggested in the search for an explanation for the survival disparity include differences in the diagnostic interval (i.e. the time from healthcare is sought until diagnosis [Citation5]), the presence of comorbidities and the access to and quality of treatment [Citation1]. Studies on stage distribution and survival indicate that the former may be of particular relevance for explaining the relatively low survival in Denmark and thus to the survival disparity between Denmark and Sweden. For example, Maringe et al. [Citation19] found a more adverse stage distribution for colorectal cancer in Denmark, with long diagnostic intervals as one suggested explanation for this, whereas unequal access to optimal treatment may be a more plausible explanation for the relatively low survival rates in the UK. Many of the potential explanations above are the focus of further in-depth research in the ICBP and are currently being studied. Thus, Module 4 of the ICBP is testing the hypothesis that differences in the diagnostic interval can contribute to the difference in cancer outcomes by closely exploring cancer patient pathways in among other Denmark and Sweden, and Module 5 seeks to investigate the effect of comorbidity on cancer survival [Citation13]. Differences in the screening program in Denmark and Sweden have also been mentioned as a possible factor for the survival disparity [Citation20]. Thus, compared to Sweden, Denmark has had a late implementation of a national breast cancer screening program, which may help explain the lower survival of breast cancer [Citation21].

Comparison with other studies

Encouragingly, most Danish and Swedish respondents reported that they would go to their doctor as soon as they noticed any breast changes or rectal bleeding. This is consistent with Robb et al.’s findings [Citation10] that the majority of respondents anticipated a short patient interval if they noticed a lump or swelling or unexplained bleeding. However, in the present as well as in Robb et al.’s study, the patient interval was assessed using a hypothetical question in which respondents were asked how long it would take them to go to the doctor if they noticed the specific symptom. Not surprisingly, the anticipated patient interval assessed among the general population is shorter than what has been reported in the patient interval literature for patients with breast or colorectal cancer [Citation22,Citation23]. For example, a Danish study found that the median patient interval was 28 days in colorectal cancer patients [Citation22]. This discrepancy between a hypothetical situation and a real-life situation may be explained in part by competing priorities, formal and informal barriers to healthcare seeking and negative beliefs about cancer, which may merely affect actual behavior [Citation12,Citation24]. Formal barriers include, among others, the way healthcare is organized. Healthcare in Denmark and Sweden is similar in the sense that the systems are primarily based on general taxation and characterized by universal access [Citation25]. In contrast to Denmark, however, Sweden has a fee per visit to the general practitioner (GP). The fee is typically SEK 100–300 and includes a cost limit which ensures that patients will not pay more than SEK 1100 in a 12-month period [Citation26]. Co-payments in primary care are generally considered a barrier to access [Citation27] although this barrier may not be captured by the hypothetical question. Informal barriers for healthcare seeking for symptoms that may be indicative of cancer can relate to worry of wasting the GP’s time as well as about what the GP might find. There are some differences between Denmark and Sweden in respect to the informal barriers to healthcare seeking [Citation12]; however, these have also been assessed using hypothetical statements and again informal barriers may affect actual behavior to a greater extent than anticipated behavior. In relation to negative beliefs about cancer, the ICBP study from Module 2 by Forbes et al. [Citation12] found that approximately 26% of the Danish respondents and 23% of the Swedish respondents aged 50 years and older agreed that ‘a diagnosis of cancer is a death sentence’. In comparison to the Swedish respondents, the Danish respondents consistently appeared to have a more pessimistic view on cancer. Negative beliefs about cancer may affect healthcare seeking when a possible cancer threat is experienced, and this may help explain the discrepancy between the patient interval reported by the general population and the patient interval reported by cancer patients. Lastly, it should be noted that neither of the two measures of the patient interval may be optimal. The former has limitations due to the hypothetical nature of the question and the latter has limitations because the patient interval is self-reported, and the time estimates may therefore be affected by the fact that the respondents have received a cancer diagnosis [Citation28].

We only studied differences in awareness of three of 11 symptoms examined by the ABC measure. However, the finding that the Danish sample had higher awareness of symptoms of cancer than the Swedish sample is not confined to the symptoms examined in the present study. Higher symptom awareness in Denmark than in Sweden is found for 10 of the 11 symptoms examined by the ABC measure among adults aged 30 years and older (unpublished data). That respondents from Denmark have higher symptom awareness than respondents from Sweden is also shown in the study by Forbes et al., [Citation12] mentioned above. Forbes et al. [Citation12] found that a mean of 7.7 symptoms of cancer were recognized in Sweden as opposed to 8.4 in Denmark. Again, it should be noted that Forbes et al.’s study merely included the age group 50 years and older (total 4039 people from Denmark and Sweden).

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no international, comparative study of equivalent magnitude focusing on cancer awareness and healthcare seeking.

An advantage of comparing Denmark and Sweden is that the ICBP sampling frame for these two countries was based on national population registers as opposed to the random probability sampling frames applied in Australia, Canada, England, Northern Ireland and Wales [Citation12]. Also, the ABC measure has shown to have satisfactory psychometric properties and since Denmark and Sweden have many linguistic similarities and great effort has been put on achieving ABC measures in Danish and Swedish that are conceptually and culturally equivalent [Citation16], we do not expect to find great measurement bias in the ABC items used for this study.

Nevertheless, it is a limitation that about 20% of both the Danish and the Swedish study bases were not available for the telephone interview and, furthermore, that only approximately one quarter of the persons approached participated in the study. The reasons for this included: research protection in Denmark (i.e. publicly recorded rejection to be contacted for research purposes), lack of telephone contact information, and refusal to participate either immediately or after being given information about the study. Moreover, it should be noted that the two Swedish healthcare regions included, i.e. Uppsala-Örebro and Stockholm-Gotland have higher average levels of educational attainment than the country as a whole [Citation29]. These factors may have resulted in an underrepresentation of people with a lower socio-economic position (SEP) and people belonging to ethnic minorities in the study. These are population groups which are known to have lower symptom awareness [Citation10,Citation30] and this selection bias may have resulted in an overestimation of awareness of these three cancer symptoms in both countries, but we are inclined to believe that the estimates of the associations have not been considerably affected. However, it is important that forthcoming surveys consider strategies to increase the response among people with a lower SEP and people belonging to ethnic minorities. These strategies might include using more resources on translators and multilingual interviewers in order not to exclude individuals due to linguistic barriers.

The categorization of anticipated patient interval for any breast changes and rectal bleeding may seem arbitrary. However, as there are neither guidelines regarding frequency or persistency of these symptoms nor consensus about the optimal time to wait before seeking healthcare, the cut-off of two weeks was chosen as a pragmatic and lenient time frame for breast changes and rectal bleeding.

It is important to note that this is an explorative, ecological study not specifically designed to test whether cancer awareness and the patient interval in the two countries are associated with cancer survival. Data on cancer survival are collected retrospectively, whereas the questions on anticipated patient interval refers to anticipated future behavior which is therefore associated more with cancer survival in the future. To conclude, it is interesting that this comparison of Denmark and Sweden, two Nordic countries with large differences in survival from common cancers, finds the highest awareness of symptoms of cancer and the shortest anticipated patient interval in Denmark, the country with the lowest cancer survival among the two.

Ethics approval

The Danish study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. no. 2011-41-6237) and the Danish Health and Medicines Authority. In accordance with the Central Denmark Region Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics, the study needed no further approval (Report no. 128/2010). The Swedish study was approved by the research ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet (Ref. no. 2011/699-31/2).

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. In Denmark, the study was supported financially by the Danish Cancer Society, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Faculty of Health at Aarhus University, the Tryg Foundation (J.no. 7-11-1339), the Danish Health and Medicines Authority and the Research Center for Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care (CaP). In Sweden, the funding sources were the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, the Strategic Research Program in Care Sciences, Umeå University and Karolinska Institutet.

References

- Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet 2011;377:127–38.

- NORDCAN [Internet]. The NORDCAN project. Cancer fact sheets [updated 2015 July 9; cited 2015 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www-dep.iarc.fr/NORDCAN/English/frame.asp.

- Engeland A, Haldorsen T, Dickman PW, Hakulinen T, Moller TR, Storm HH, et al. Relative survival of cancer patients–a comparison between Denmark and the other Nordic countries. Acta Oncol 1998;37:49–59.

- Richards MA. The National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative in England: assembling the evidence. Br J Cancer 2009;101 (Suppl 2):S1–4.

- Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G, Walter FM, Emery J, Scott S, et al. The Aarhus statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1262–7.

- Ramirez AJ, Westcombe AM, Burgess CC, Sutton S, Littlejohns P, Richards MA. Factors predicting delayed presentation of symptomatic breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet 1999;353:1127–31.

- Smith LK, Pope C, Botha JL. Patients' help-seeking experiences and delay in cancer presentation: a qualitative synthesis. Lancet 2005;366:825–31.

- Macdonald S, Macleod U, Campbell NC, Weller D, Mitchell E. Systematic review of factors influencing patient and practitioner delay in diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal cancer. Br J Cancer 2006;94:1272–80.

- Macleod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, Macdonald S, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: evidence for common cancers. Br J Cancer 2009;101 (Suppl 2):S92–S101.

- Robb K, Stubbings S, Ramirez A, Macleod U, Austoker J, Waller J, et al. Public awareness of cancer in Britain: a population-based survey of adults. Br J Cancer 2009;101 (Suppl 2):S18–23.

- Keighley MR, O'morain C, Giacosa A, Ashorn M, Burroughs A, Crespi M, et al. Public awareness of risk factors and screening for colorectal cancer in Europe. Eur J Cancer Prev 2004;13:257–62.

- Forbes LJ, Simon AE, Warburton F, Boniface D, Brain KE, Dessaix A, et al. Differences in cancer awareness and beliefs between Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): do they contribute to differences in cancer survival? Br J Cancer 2013;108:292–300.

- Butler J, Foot C, Bomb M, Hiom S, Coleman M, Bryant H, et al. The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership: an international collaboration to inform cancer policy in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Health Policy 2013;112:148–55.

- Pedersen CB, Gotzsche H, Moller JO, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull 2006;53:441–9.

- Skatteverket SPAR [Internet]. Om SPAR. English summary [updated 2014 Nov 18; cited 2015 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.statenspersonadressregister.se/ovre-meny/english-summary.html

- Simon AE, Forbes LJ, Boniface D, Warburton F, Brain KE, Dessaix A, et al. An international measure of awareness and beliefs about cancer: development and testing of the ABC. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001758.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Cough. 2010. [updated 2010 May 6; cited 2014 Dec 8]. Available from: http://cks.nice.org.uk/cough#!scenariorecommendation:3,2014.

- Dalton SO, Schuz J, Engholm G, Johansen C, Kjaer SK, Steding-Jessen M, et al. Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003: Summary of findings. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:2074–85.

- Maringe C, Walters S, Rachet B, Butler J, Fields T, Finan P, et al. Stage at diagnosis and colorectal cancer survival in six high-income countries: a population-based study of patients diagnosed during 2000-2007. Acta Oncol 2013;52:919–32.

- Walters S, Maringe C, Butler J, Rachet B, Barrett-Lee P, Bergh J, et al. Breast cancer survival and stage at diagnosis in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK, 2000-2007: a population-based study. Br J Cancer 2013;108:1195–208.

- Tryggvadottir L, Gislum M, Bray F, Klint A, Hakulinen T, Storm HH, et al. Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with breast cancer in the Nordic countries 1964-2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Acta Oncol 2010;49:624–31.

- Pedersen AF, Hansen RP, Vedsted P. Patient delay in colorectal cancer patients: associations with rectal bleeding and thoughts about cancer. PLoS One 2013;8:e69700.

- Hansen RP, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Sondergaard J, Olesen F. Time intervals from first symptom to treatment of cancer: a cohort study of 2,212 newly diagnosed cancer patients. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:284.

- Scott SE, Grunfeld EA, Auyeung V, McGurk M. Barriers and triggers to seeking help for potentially malignant oral symptoms: implications for interventions. J Public Health Dent 2009;69:34–40.

- Wadmann S, Strandberg-Larsen M, Vrangbaek K. Coordination between primary and secondary healthcare in Denmark and Sweden. Int J Integr Care 2009;9:e04

- 1177 Vårdguiden [Internet]. Patient Fees [updated 2015 Feb 8; cited 2015 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www.1177.se/Other-languages/Engelska/Regler-och-rattigheter/Patientavgifter/.

- Kiil A, Houlberg K. How does copayment for health care services affect demand, health and redistribution? A systematic review of the empirical evidence from 1990 to 2011. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:813–28.

- Andersen RS, Vedsted P, Olesen F, Bro F, Sondergaard J. Patient delay in cancer studies: a discussion of methods and measures. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:189.

- Statistics Sweden [Internet]. Population 16-95 + years of age by region, level of education, age and sex. Year 2008 - 2014 [updated 2015 May 22; cited 2015 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__UF__UF0506/UtbBefRegion/?rxid=4f10d216-a05e-4d4d-8aee-abb3723064fc.

- Hvidberg L, Pedersen AF, Wulff CN, Vedsted P. Cancer awareness and socio-economic position: results from a population-based study in Denmark. BMC Cancer 2014;14:581.