Abstract

Background: Cancer in a child is associated with a significant impact on parental employment. We assessed the proportions of parents of survivors and bereaved parents working and reporting sick leave five years after end of successful treatment (ST)/child’s death (T7) compared with one year after end of ST/child’s death (T6) and the association between partial post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and work situation and sick leave at T7.

Participants and procedure: The sample included 152 parents of survivors (77 mothers, 75 fathers) and 42 bereaved parents (22 mothers, 20 fathers) of children diagnosed with cancer in Sweden.

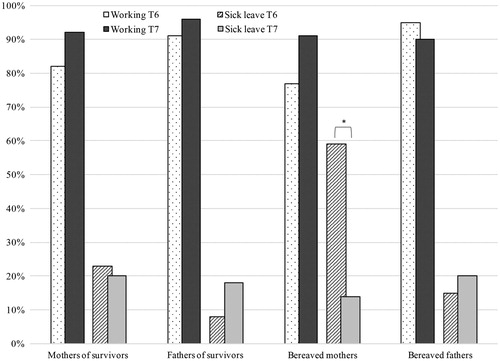

Results: The proportions of parents working or reporting sick leave did not differ among mothers and fathers of survivors (92% vs. 96% working, 20% vs. 18% on sick leave) or among bereaved mothers and fathers (91% vs. 90% working, 14% vs. 20% on sick leave) at T7. There was no change from T6 to T7 in the proportion of fathers working (fathers of survivors 91% vs. 96%, bereaved fathers 95% vs. 90%). Although more mothers of survivors (92% vs. 82%) and bereaved mothers (91% vs. 77%) worked at T7 than at T6, this increase was not significant. Fewer bereaved mothers reported sick leave at T7 than at T6 (14% vs. 59%, p < 0.05). Although more fathers reported sick leave at T7 than at T6 (fathers of survivors 18% vs. 8%, bereaved fathers 20% vs. 15%), this was not significant. Partial PTSD was not associated with parents’ work situation or sick leave at T7.

Conclusion: Results suggest little adverse effect on work situation and sick leave among parents of survivors and bereaved parents five years after end of ST/child’s death from cancer. However, the pattern of change observed differed between parents, which could potentially indicate possible delayed consequences for fathers not captured in the present paper.

Despite improved survival rates, with an overall five-year survival approaching 80% in Sweden [Citation1], having a child diagnosed with cancer has a significant impact on all family members [Citation2]. A substantial number of parents of children diagnosed with cancer experience significant occupational and financial consequences including employment and income loss, affected work ability, reduced work hours, and sick leave, both during and after treatment completion [Citation3,Citation4]. The impact on parental income, employment and sick leave is greatest during treatment and the effect on employment and earnings is greater among mothers than fathers [Citation3,Citation5–8]. There is a lack of longitudinal studies with long-term follow-up on the impact of childhood cancer on parents’ work situation. However, some studies have found a majority of families reporting employment and income levels comparable with pre-diagnosis levels within five years following diagnosis [Citation3,Citation5]. One large population-based Norwegian study, where the majority of children were diagnosed more than five years earlier, found limited adverse effects of childhood cancer on parents’ employment [Citation5].

We have reported on the impact of childhood cancer on parental work situation, sick leave and income in a longitudinal study from the time of diagnosis until one year following end of the child’s treatment [Citation9]. Results showed that although parents reduced their work hours following their child’s diagnosis, there were no differences in the proportions of mothers and fathers working at one year following end-of-treatment. However, results showed that the proportion of fathers working at one-year follow-up was lower than prior to the child’s diagnosis, whereas the proportion of mothers who were working had returned to pre-diagnosis levels. With regard to sick leave, more mothers than fathers reported being on sick leave throughout the entire study period. Compared with the time of diagnosis, more mothers were on sick leave at one year after end-of-treatment while no such effect was found for fathers. The present study extends these findings with follow-up data on the work situation of parents at five years after end of successful treatment (ST) or the child’s death.

There is a growing body of evidence finding childhood cancer survivors and their parents at increased risk for psychological problems including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) up to several years after treatment completion [Citation10,Citation11]. Five years following end of ST or a child’s death, 19% and 8% of mothers and fathers of survivors, and 20% and 35% of bereaved mothers and fathers, report at least partial PTSD, with mothers and bereaved parents at particular risk for post-traumatic stress symptoms [Citation12]. Partial PTSD or sub-syndromal PTSD have been associated with comorbid psychiatric symptoms almost to the same extent as full PTSD and is an important diagnostic entity in populations exposed to serious illness [Citation13]. In addition, a negative association between psychiatric disorders, including PTSD, and being employed has been documented in epidemiological studies [Citation14].

The purpose of the present study was to explore the work situation and sick leave reported by parents of children previously treated for cancer in Sweden, at five years following end of ST or a child’s death. Specifically, the study aimed to assess the proportion of parents working and on sick leave at five years after end of ST or a child’s death and whether proportions differed from that reported at one year after end of ST or a child’s death. In addition, since parents’ work opportunities may also be influenced by mental health disorders [Citation14], we also aimed to assess the association between partial PTSD and work situation and sick leave at five years after end of ST or a child’s death.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were parents of children diagnosed with cancer at four pediatric oncology centers in Sweden. Full details of participants and procedures have been described elsewhere [Citation9,Citation12,Citation15]. In brief, parents (including step-parents) were invited to participate if they were Swedish and/or English speaking parents of a child aged ≤18 years, with a primary cancer diagnosis (within the past 14 days), scheduled for chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (not applicable to CNS tumors), and with access to a telephone. Recruitment was carried out during an 18-month period between 2002 and 2004.

This longitudinal study involved assessments at seven time-points using structured telephone interviews: one week (T1), two (T2) and four months (T3) after diagnosis, one week post end of ST or six months after stem cell transplantation (T4), three months post end of ST or nine months after transplantation/child’s death (T5), one year after end of ST or 18 months after transplantation/child’s death (T6), and five years after end of ST or transplantation/child’s death (T7). Ethical approval was granted by the local ethical committees at each participating center (Dnr: 02-006) and the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (Dnr: 2008/109) and oral informed consent was obtained from all participants. Two hundred and ninety parents participated at T1, of whom 251 (87%) participated at T6 and 194 (67%) participated at T7. The present study includes data collected at T6 and T7 and study analyses were performed on 194 parents of 107 children.

Measures

Information on parents’ age at the child’s diagnosis (<30, 31–39, ≥40), marital status at T7 (partner, no partner), parents’ education level at T1 (nine years, upper secondary, university), work situation at T1 (working, not working), custody arrangement at T7 (joint custody, child of age i.e. ≥18 years, sole custody, no custody), parents having other children or none at the child’s diagnosis (i.e. siblings; none, one or two, three or more) as well as the child’s age at diagnosis (0–3, 4–7, 8–12, 13–18) and child’s gender (girl, boy) were obtained by telephone interview. Clinical information on the child’s cancer diagnosis (categorized as ‘leukemia’, ‘CNS tumor’ or ‘other solid tumor’) was gathered from medical charts.

Data on work situation and sick leave were collected using structured telephone interviews at all assessment points. At T6, parents provided information on work situation (working, not working) and type of employment (full- or part-time) including reasons for working part-time or not working (e.g. sick leave, unemployed, retired, parental leave, other). Parents who reported working full- or part-time were categorized as ‘working’. Parents reporting sick leave as a reason for not working at T6 were categorized as ‘on sick leave’ (whether fully or partly on sick leave).

At T7, questions corresponding to a nationwide survey of living conditions in Sweden (ULF, by Swedish acronym [Citation16]) were used to collect information on employment and sick leave. Parents whom reported currently working (full- or part-time), were self-employed or studying, were defined as ‘working’ (including parents in part-time work combined with part-time parental leave or part-time studying). Among 142 parents of survivors working at T7, 98 worked full-time, 25 part-time, 15 were self-employed, and four reported studying. Of 38 bereaved parents who were working at T7, 29 worked full-time, five part-time, two were self-employed and two were studying. Parents reporting full-time parental leave (one parent of a survivor), or reported not presently working (e.g. retired or receiving sickness benefits [four parents of survivors and three bereaved parents], unemployment [four parents of survivors]) were defined as ‘not working’. Parents reported whether they had been on sick leave during the past two weeks prior to the T7 assessment, including the number of days on sick leave. This information was used to define parents’ sick leave status at T7 and was defined as ‘on sick leave’ (irrespective of number of days) or ‘not on sick leave’ (no days on sick leave during the past two weeks). Working and sick leave were assessed as two separate variables and are therefore not mutually exclusive. Thus, a parent can belong to the ‘working’ group on the work situation variable and the ‘on sick leave’ group on the sick leave status variable, as sick leave at T7 refers to sick leave during the past two weeks only. Information on work situation at T7 was missing for one mother of a survivor. Two mothers and one father of survivors had missing data on sick leave at T7.

We have previously reported on the development of post-traumatic stress symptoms among these parents from T1 to T7 [Citation12]. In the present study we used the same criteria as in our previous study for probable ‘partial PTSD’ (i.e. scores ≥3 on at least one symptom of reexperiencing, avoidance and hyper-arousal [Citation17]) on the PTSD Checklist Civilian Version (PCL-C [Citation18]) to explore differences in work situation and sick leave at T7. Data on the PCL-C were missing for two bereaved mothers and three bereaved fathers at T7.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to present parent and child characteristics. To assess associations between parents of survivors (mothers and fathers) or bereaved parents (mothers and fathers) and work situation and sick leave status, χ2-tests were used. Similarly, differences in the proportions of parents working or on sick leave among parents with or without partial PTSD were analyzed using χ2-tests. McNemar’s significance test was conducted to assess changes in the proportions of parents of survivors and bereaved parents working or on sick leave from T6 to T7. Results are presented as numbers (n) and percentages (%), where p-values <0.05 represent statistical significance. Differences between participants (n = 194) and non-participants (n = 94) on socio-demographic and child characteristics were assessed using χ2-tests. No significant differences between non-participants and participants at T7 were observed regarding the number of mothers and fathers, parents’ age, marital status, work situation at diagnosis, and the child’s diagnosis (p-values all >0.05). However, more non-participants than participants reported a lower educational level (χ2=9.10, p < 0.05) and had no other children than the child diagnosed with cancer (χ2=7.80, p < 0.05). Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Parent and child characteristics are shown in . Of 194 parents of 107 children at T7, 152 (77 mothers, 75 fathers) were parents of survivors and 42 (22 mothers, 20 fathers) were bereaved parents. At T7, 83 children were alive, and 24 children were deceased.

Table 1. Parent (n = 194) and child characteristics (n = 107) at T7.

Work situation

The majority of parents of survivors were working both at T6 and T7 (n = 128, 84%). The proportion of parents of survivors working significantly increased from T6 to T7 (n = 131, 86% and n = 142, 94%, respectively, p < 0.05). There were no differences in the proportion of mothers of survivors working (n = 70, 92%) compared with fathers of survivors (n = 72, 96%) at T7 (p = 0.31), though a trend for an increase in the proportion of mothers of survivors working from T6 to T7 was observed (n = 63, 82% and n = 70, 92%, respectively, p = 0.06). No significant difference was observed regarding fathers of survivors working between T6 (n = 68, 91%) and T7 (n = 72, 96%, p = 0.22).

A majority of bereaved parents were working both at T6 and T7 (n = 32, 76%). No significant difference was found between T6 and T7 among bereaved parents working (n = 36, 86% and n = 38, 91%, respectively, p = 0.75). There were no differences in the proportion of bereaved mothers working (n = 20, 91%) compared with bereaved fathers working (n = 18, 90%) at T7 (p = 0.92). Although the proportion of bereaved mothers working increased from T6 (n = 17, 77%) to T7 (n = 20, 91%), this was not statistically significant (p = 0.45). No changes were observed regarding bereaved fathers working between T6 (n = 19, 95%) and T7 (n = 18, 90%, p = 0.99). illustrates the proportions of parents of survivors and bereaved parents working at T6 and T7.

Sick leave

Twenty-four parents of survivors (16%) reported sick leave at T6, whereas 28 parents of survivors (19%) reported being on sick leave at T7, with 4% (n = 6) of parents of survivors reporting sick leave both at T6 and T7. Among parents of survivors on sick leave at T7, almost one-third (n = 8, 30%) had been off work for at least seven days. There were no significant differences between mothers and fathers of survivors in the proportions reporting sick leave at T7 (n = 15, 20% and n = 13, 18%, respectively, p = 0.70). A non-significant increase in the proportion of fathers of survivors on sick leave was observed between T6 and T7 (n = 6, 8% and n = 13, 18%, respectively, p = 0.14), and a non-significant decrease in the proportion of mothers of survivors on sick leave from T6 and T7 was observed (n = 18, 23% and n = 15, 20%, respectively, p = 0.68).

Among bereaved parents, 16 (38%) reported sick leave at T6 and seven (17%) at T7. Two (5%) bereaved parents reported sick leave both at T6 and T7. More than one-third of bereaved parents on sick leave at T7 (n = 3, 43%) had been off work for at least seven days. There were no significant differences in the proportions of bereaved mothers and fathers on sick leave at T7 (n = 3, 14% and n = 4, 20%, respectively, p = 0.58). However, the proportion of bereaved mothers on sick leave significantly decreased from T6 (n = 13, 59%) to T7 (n = 3, 14%, p < 0.05), whereas no significant difference was observed in the proportions of bereaved fathers on sick leave at T6 and T7 (n = 3, 15% and n = 4, 20%, respectively, p = 0.90). illustrates the proportions of parents of survivors and bereaved parents reporting sick leave at T6 and T7.

Work situation, sick leave and partial PTSD

The proportions of parents working and on sick leave at T7 are shown in for parents reporting partial PTSD or no PTSD at T7. There were no differences in the proportions of mothers and fathers of survivors or bereaved mothers and fathers working or on sick leave among those reporting partial PTSD compared with those who did not fulfill criteria for partial PTSD (p-values all >0.05, ).

Table 2. Proportion of parents working and reporting sick leave at T7 among parents of survivors and bereaved parents with or without partial PTSD at T7.

Discussion

Interpretation of results

The results of this five-year follow-up study suggest that the work situation among parents of survivors and bereaved parents have normalized by five years following the end of ST or a child’s death from cancer. These results are in line with previous studies showing that a majority of parents are able to return to stable income and employment within five years after diagnosis [Citation3,Citation5].

We have previously reported on the consequences of having a child with cancer on work situation, sick leave and income in this cohort and shown that although mothers reported more sick leave, their work situation at one year after end-of-treatment appeared normalized, whereas fewer fathers were working compared with pre-diagnosis [Citation9]. A similar pattern was observed in the present study, where the mothers’ situation appeared to have improved, even more so than previously, with a non-significantly larger proportion of mothers of survivors working at five-year follow-up compared with one-year follow-up. A significant decrease in sick leave was observed among bereaved mothers, and although the increase was not significant, the proportion of bereaved mothers working was greater at five-year follow-up than at one-year follow-up. These results are in line with one large-scale registry-based study (n = 1.2 million) including data from the entire Norwegian population of working age parents of children with and without cancer, followed from 1990 to 2002 [Citation5]. Results showed that parents’ employment is not generally adversely affected in the long-term. Interestingly, an increase in employment rates among bereaved mothers was observed [Citation5]. One explanation may be that although bereavement negatively influences work ability in parents [Citation19,Citation20], caregiving responsibilities are decreased following the death of a child, which may enable return to work.

The proportion of fathers of survivors or bereaved fathers working did not significantly change from the previous assessment, and although the proportion of fathers of survivors reporting sick leave increased by 10% from one-year follow-up to five-year follow-up, this change was not statistically significant. It is possible that a shift in priorities regarding the work- and family situation may account for the observation that the proportion of fathers working at follow-up had not returned to pre-diagnosis levels. Still, the proportion of fathers working was very high, which may suggest a ceiling effect. Indeed, the proportion of parents in work in this study appear somewhat higher than what has been observed in a random sample from the general population, where the proportion of women and men aged 25–54 reporting working ranged from 70% to 88% (ULF survey [Citation16]). The finding that nearly all parents were working at five-year follow-up should be understood in light of the social security system in Sweden that guarantees generous benefit levels for its residents when absent from paid work due to own ill health or care of a sick child. Certain welfare state policies including job security legislations, e.g. the Employment Protection Act [Citation21], enables individuals to be absent from work without having to give up their employment thus facilitating return to work after periods of absence. The generalizability of findings from the present study may thus be limited to countries with similar welfare systems.

The non-significant gender differences in this study are of interest since previous studies with shorter follow-up periods have reported differences between mothers and fathers [Citation6–8]. With a long-term perspective applied, no such differences were observed. A more pronounced effect on mothers’ work situation and income has been found earlier in the child’s illness trajectory with improvement over time [Citation9]. One would expect a similar pattern of change among fathers, however, more fathers reported sick leave at five years than at one year after end of ST or a child’s death in the present study. Although this increase was not statistically significant, it may be one indication that fathers may be more vulnerable to late consequences (e.g. impacts on career, salary and pension development) not captured in the present paper. Notably, we have previously observed a delayed effect in a sub-group of fathers in the development of PTSD [Citation12].

Although significant negative associations of common mental disorders (including PTSD) with employment have been documented in epidemiological research [Citation13], we did not find an association between partial PTSD and parents work situation or sick leave five years after end-of-treatment or a child’s death. However, this lack of association may be due to the limited sample size.

Strengths and limitations

The longitudinal design, the long-term follow-up period, and inclusion of both mothers and fathers of survivors as well as bereaved parents are strengths of the study. Although the response rate in this study appeared somewhat lower than at earlier assessments [Citation9], non-participants did not differ significantly on several characteristics from parents responding at T6 and T7. However, non-participants had lower education level, which may have overestimated the proportions working. Limitations include the relatively small sample size, which reduced the statistical power to detect possible associations, and the very low number of parents not working at T7 did not allow for multivariable analyses to determine associations between socio-demographic variables and child illness characteristics and outcomes. Further, information on sick leave was collected by self-report. However, the sensitivity and specificity of self-reports compared with registry-based sickness absence are acceptable for periods of sick leave not exceeding seven days [Citation22]. In the present study, the majority of parents of survivors (70%) and bereaved parents (57%) reported sick leave of duration less than one week at T7. In addition, the recall period of two weeks at T7 was well below a recommended recall period of less than two months for a valid measure of absence lengths [Citation23].

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge this study is the first to investigate the impact on parents’ work situation and sick leave in a longitudinal study among parents of survivors and bereaved parents five years following end of ST or a child’s death from cancer. Differences between mothers’ and fathers’ work situation and sick leave among parents of survivors and bereaved parents appear to have diminished by five years after end-of-treatment or a child’s death, suggesting a limited adverse effect of childhood cancer on parental work situation and sick leave in the long-term for mothers as well as for fathers. However, the pattern of change observed differed for mothers and fathers, which could potentially indicate possible delayed consequences for fathers not captured in the present paper. In addition, longer term absences from work following a child’s cancer treatment or death may still contribute to impacted salary and career development among these parents. Using relatively crude measures of labor market outcomes, it was not possible to captures such potential effects in the present study, which warrants further attention.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (grant numbers 01 6368, 02 0274 and 03 0228), the Swedish Research Council (grant number K2008-70X-20836-01-3) and the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation (grant numbers 02/004 and 05/030). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The funders do not bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all parents who took part in the study for their contribution. We also thank research assistant Susanne Lorenz who interviewed most parents.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Gustafsson G, Kogner P, Heyman M. Childhood cancer incidence and survival in Sweden 1984–2010. In: Report from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry. Karolinska Institutet: Stockholm, 2013. Available from: http://www.cceg.ki.se/documents/ChildhoodCancerIncidenceandSurvivalinSweden1984_2010.pdf. (Accessed on 2016-03-04).

- Long KA, Marsland AL. Family adjustment to childhood cancer: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2011;14:57–88.

- Limburg H, Shaw AK, McBride ML. Impact of childhood cancer on parental employment and sources of income: a Canadian pilot study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;51:93–8.

- Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, Evans NT, Ellis SJ, Cohn RJ. It's more than dollars and cents: the impact of childhood cancer on parents' occupational and financial health. J Psychosoc Oncol 2014;32:602–21.

- Syse A, Larsen IK, Tretli S. Does cancer in a child affect parents' employment and earnings? A population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol 2011;35:298–305.

- Eiser C, Upton P. Costs of caring for a child with cancer: a questionnaire survey. Child Care Health Dev 2007;33:455–59.

- Miedema B, Easley J, Fortin P, Hamilton R, Mathews M. The economic impact on families when a child is diagnosed with cancer. Curr Oncol 2008;15:173–8.

- Clarke NE, McCarthy MC, Downie P, Ashley DM, Anderson VA. Gender differences in the psychosocial experience of parents of children with cancer: a review of the literature. Psychooncol 2009;18:907–15.

- Hovén E, von Essen L, Lindahl Norberg A. A longitudinal assessment of work situation, sick leave, and household income of mothers and fathers of children with cancer in Sweden. Acta Oncol 2013;52:1076–85.

- Bruce M. A systematic and conceptual review of posttraumatic stress in childhood cancer survivors and their parents. Clin Psychol Rev 2006;26:233–56.

- Ljungman L, Cernvall M, Grönqvist H, Ljótsson B, Ljungman G, von Essen L. Long-term positive and negative psychological late effects for parents of childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e103340.

- Ljungman L, Hovén E, Ljungman G, Cernvall M, von Essen L. Does time heal all wounds? A longitudinal study of the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of survivors of childhood cancer and bereaved parents. Psychooncol 2015;24:1792–98.

- Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from wave 2 of the National epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Anxiety Disord 2011;25:456–65.

- Mojtabai R, Stuart EA, Hwang I, Susukida R, Eaton WW, Sampson N, et al. Long-term effects of mental disorders on employment in the National comorbidity survey ten-year follow-up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:1657–68.

- Pöder U, Ljungman G, von Essen L. Posttraumatic stress disorder among parents of children on cancer treatment: a longitudinal study. Psychooncol 2008;17:430–37.

- Statistics Sweden (Statistiska Centralbyrån): Living conditions surveys (ULF/SILC); Available from: http://www.scb.se/en_/Finding-statistics/Statistics-by-subject-area/Living-conditions/Living-conditions/Living-Conditions-Surveys-ULFSILC/. (Accessed on 2016-03-04).

- Breslau N, Lucia VC, Davis GC. Partial PTSD versus full PTSD: an empirical examination of associated impairment. Psychol Med 2004;34:1205–14.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the 9th Annual Conference of the ISTSS, San Antonio, TX, 1993.

- Rogers CH, Floyd FJ, Seltzer MM, Greenberg J, Hong J. Long-term effects of the death of a child on parents' adjustment in midlife. J Fam Psychol 2008;22:203–11.

- Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, Bjork O, Steineck G, Henter JI. Care related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:9162–71.

- Available from: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/workingpapers/soci/w13/summary_en.htm. (Accessed on 2016-03-04).

- Stapelfeldt CM, Jensen C, Andersen NT, Fleten N, Nielsen CV. Validation of sick leave measures: self-reported sick leave and sickness benefit data from a Danish national register compared to multiple workplace-registered sick leave spells in a Danish municipality. BMC Pub Health 2012;12:661.

- Severens JL, Mulder J, Laheij RJ, Verbeek AL. Precision and accuracy in measuring absence from work as a basis for calculating productivity costs in The Netherlands. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:243–49.