Abstract

Fat embolism to the systemic circulation in polytrauma patients is very common. The fat embolism syndrome (FES), however, is a rare condition. We describe a case of traumatic femur fracture with FES that was presented as acute tonsillar herniation (coning) and brain death postoperatively. We believe that in this case the prone position and moderate hypercapnia contributed to the acute coning.

Key words::

Introduction

Fat embolism to the systemic circulation in polytrauma patients is very common and up to 80% of trauma patients have had fat embolization at autopsy (Citation1,2). The fat embolism syndrome (FES), however, is a rarer condition consisting of a constellation of neurological, pulmonary, cutaneous, and hemodynamic changes. An incidence of 1% following long-bone fractures has been reported (Citation3,4). There are a vast number of publications describing different presentations of fat embolism. However, cerebral edema and fatal tonsillar herniation is an unusual presentation of FES described in the literature only a few times (Citation5-7). In one case, cerebral fat embolism syndrome caused brain death after long-bone fractures and acetazolamide therapy (Citation8). We describe a case of traumatic femur fracture with FES that was presented as acute tonsillar herniation (coning) and brain death postoperatively.

Case report

A 20-year-old man was involved in a motor vehicle accident resulting in an isolated fracture of the right mid femur. The patient was awake and had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15 at admission to the emergency department. The patient was examined and stabilized according to the advanced trauma life support (ATLS) principles. Whole-body computerized tomography did not show any head injury. There were multiple displaced costal fractures on the right side with lung contusion and minimal pneumothorax that did not need drainage.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) while waiting for surgical stabilization of the fracture. During the 6-hour preoperative stay in the ICU, the patient was stable and awake. The patient was operated upon in general anesthesia. Intramedullary insertion of a femur nail was attempted but was quite difficult to achieve. A great deal of manipulation and drilling was required in order to insert a 400 mm nail. The patient was stable peroperatively.

Three hours later he was transported back to the ICU, still intubated and on 0.5 fraction inspired oxygen (FiO2). A wake-up test was performed at arrival to the ICU, and the patient seemed to be awake but suffered from pain. The patient deteriorated during the next 6 hours. He developed a high fever, and his oxygen saturation decreased. A new chest X-ray showed 2.5 cm pneumothorax that was drained successfully, but saturation continued to decrease during the next 6 hours. His oxygen demand increased ending up at 0.9 FiO2. A decision was made to increase sedation and apply a higher positive end expiratory pressure. In addition the patient was turned into a prone position.

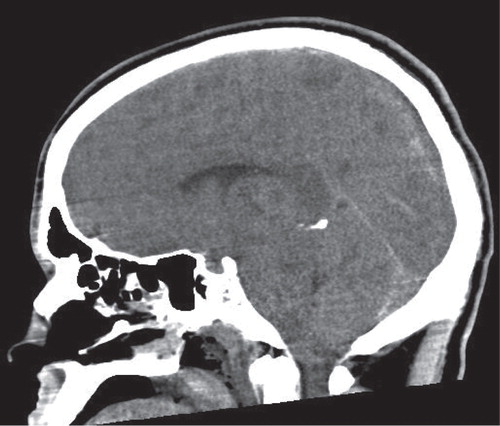

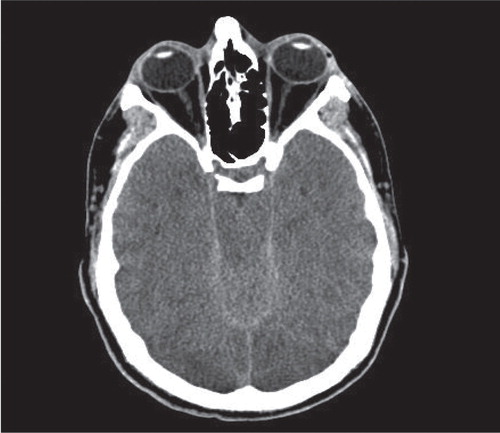

The patient was kept sedated during the next 24 hours, and the FiO2 was decreased to 0.4. Moderate hypercapnia was tolerated (7.5–8.5 kPa). A wake-up test was not performed while the patient was in the prone position but the patient's pupils were examined regularly. Upon turning the patient to a supine position, his pupils dilated and they were not responsive to light. The patient was hyperventilated and mannitol was given. In addition a computerized tomography scan (CT) of the head was performed ( and ) revealing cerebral edema and evidence of coning. CT with angiography was also performed to exclude dissection of the great vessels in the neck. No dissection was found. Examination of the patient revealed petechial hemorrhages mainly on the torso, extremities, and conjunctivas. Transesophageal echocardiography revealed no intracardiac shunting.

Twenty-four hours later the patient was declared brain dead according to the brain death clinical criteria and four-vessel angiography. Autopsy showed signs of massive fat embolism in the lungs and brain.

Discussion

We present a case of FES with all criteria of that syndrome including neurological, pulmonary, cutaneous, and hemodynamic changes.

Neurological manifestations of FES can vary from mild cognitive changes to coma, but severe cerebral edema including coning is a quite unusual presentation. Therefore one might speculate on why our patient developed such a severe cerebral edema. The patient did not have a head injury that might have been worsened postoperatively. He was awake before turning him into a prone position. Pneumothorax and lung contusion contributed to the deterioration of his pulmonary status and also delayed the diagnosis of FES. Moreover, he was deeply sedated and therefore no wake-up test was performed during the period when he was in the prone position. Prone position and deep sedation were clinically motivated because of his high FiO2. Moderate hypercapnia was also tolerated in line with the latest recommendation in managing patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Citation9).

The effect of prone position on intra-cranial pressure (ICP) has not been studied extensively. However, in one study it was found that the prone position did not influence ICP and the cerebral perfusion pressure, but significantly improved the patient's PaO2 (Citation10). In another study oxygenation was also improved but ICP increased significantly (Citation11). Theoretically speaking, turning the patient into a prone position and tilting the head to one side (at 90 degrees angle) could affect the venous return from the brain, resulting in cerebral edema. Hypercapnia induces cerebral vasodilation and increases cerebral blood flow, which might worsen the cerebral edema (Citation12). The combination of prone position and moderate hypercapnia might have contributed to the severe cerebral edema and eventually coning and brain death.

To our knowledge this is the first reported case with this combination and leading to such a tragic outcome. Deep sedation and permissive hypercapnia are established recommendations in managing severe ARDS. In addition, prone position is an effective method to improve saturation in patients needing high FiO2 (Citation13). In patients with head injuries, ICP monitoring is a routine procedure to monitor cerebral edema. In awake multitrauma patients without head injuries one would not expect a need for ICP monitoring. With the risk of FES in mind we advocate performing wake-up tests regularly.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Hulman G. The pathogenesis of fat embolism. J Pathol. 1995;176:3–9.

- Eriksson EA, Pellegrini DC, Vanderkolk WE, Minshall CT, Fakhry SM, Cohle SD. Incidence of pulmonary fat embolism at autopsy: an undiagnosed epidemic. J Trauma. 2011;71:312–15.

- Bulger EM, Smith DG, Maier R, Jurkovich GJ. Fat embolism syndrome. A 10-year review. Arch Surg. 1997;132:435–9.

- Muller C, Rahn B, Pfister U, Meinig RP. The incidence, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of fat embolism. Orthop Rev. 1994;23:107–17.

- Bracco D, Favre JB, Joris R, Ravussin A. Fatal fat embolism syndrome: a case report. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2000;12:221–4.

- Beretta L, Calvi MR, Frascoli C, Anzalone N. Cerebral fat embolism, brain swelling, and severe intracranial hypertension. J Trauma. 2008;65:E46–8.

- Etchells EE, Wong DT, Davidson G, Houston PL. Fatal cerebral fat embolism associated with a patent foramen ovale. Chest. 1993;104:962–3.

- Walshe CM, Cooper JD, Kossmann T, Hayes I, Iles L. Cerebral fat embolism syndrome causing brain death after long-bone fractures and acetazolamide therapy. Crit Care Resusc. 2007;9:184–6.

- The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–8.

- Thelandersson A, Cider A, Nellgård B. Prone position in mechanically ventilated patients with reduced intracranial compliance. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:937–41.

- Nekludov M, Bellander BM, Mure M. Oxygenation and cerebral perfusion pressure improved in the prone position. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:932–6.

- Kety SS, Schmidt CF. The effects of altered arterial tensions of carbon dioxide and oxygen on cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen consumption of normal young men. J Clin Invest. 1948;27:484–92.

- Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, Beuret P, Gacouin A, Boulain T, et al. PROSEVA Study Group. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–68.