Dear Editor

Leucocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a necrotizing vasculitis that complicates infections, malignancies, and collagen vascular diseases and can also occur as a reaction to medications (Citation1). It is difficult to distinguish clinically from a drug eruption. We present a case of drug rash resembling LCV. Diagnosis was established by skin biopsy and responded to prompt discontinuation of the medication. The case emphasizes the importance of considering skin biopsy in distinguishing a suspected drug reaction from vasculitis.

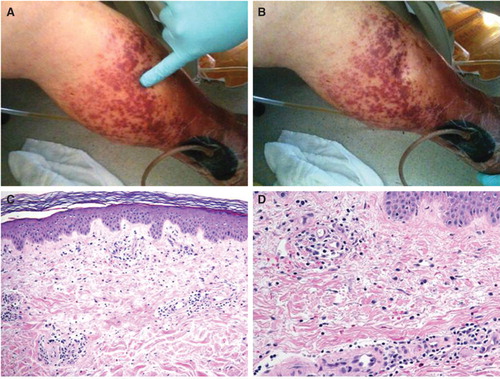

A 65-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with cellulitis of the left leg. He was started empirically on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam. Based on results of blood cultures, he was treated with oxacillin and then cefazolin for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. After three doses of cefazolin, however, the patient developed a rash on both legs and back (). The rash was palpable but non-blanching ( and ), non-tender, and there were no blisters. Laboratory investigation revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 70 mm/h (reference range 0–20 mm/h), rheumatoid factor of 20 IU/ml (reference range < 15 IU/ml), and negative antinuclear antibodies. Other significant findings included microscopic hematuria (> 50 RBCs/hpf) and microscopic proteinuria (protein/creatinine ratio 0.3; reference range 0–0.2 mg/mg of creatinine). Histopathology of skin biopsy revealed mild lymphocytic infiltration into the dermis without any evidence of fibrinoid necrosis ( and ). A diagnosis of drug rash was made, presumably due to oxacillin. Cefazolin was continued and the patient discharged home 2 weeks later with instructions to complete a 6-week course. On follow-up his rash had completely resolved.

Figure 1. Palpable purpuric rash on the left lower extremity (A and B) and back (C and D) following antibiotic therapy.

Figure 2. Demonstration of non-blanchability of the purpuric lesions (A and B). Histopathology of skin lesions from the purpuric lesions (C). The epidermis demonstrates no inflammatory changes. Within the papillary dermis there is a mild inflammatory infiltrate associated with extravasated red blood cells (× 100, H&E). The inflammatory infiltrate is composed predominately of lymphocytes with rare eosinophils (D). There are scattered extravasated red blood cells. No neutrophils are present. The vessels show no fibrinoid necrosis or fibrin thrombi (× 200, H&E).

Cutaneous LCV is characterized by a palpable purpuric rash that usually begins 7–21 days after exposure to the offending antigen, involves the lower extremities, and is accompanied by dependent lower extremity edema, abdominal and joint pains, and renal involvement. Involvement of the forearms, hands, back, sacral, and gluteal regions is less common. When fully evolved, the skin lesions form vesicles, bullae nodules, or ulcers (Citation2). Histologically, it is characterized by acute necrotizing inflammation involving small blood vessels in the upper dermis (Citation3). Drug-induced rash, on the other hand, is characterized by a superficial, mostly perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate and some eosinophilia. Interface dermatitis, characterized by epidermal basal cell damage, may also be seen with a drug rash (Citation4). The two conditions can only be distinguished histologically. The management of cutaneous LCV depends on the severity. In mild cases, support stockings and elevation of the edematous legs can be tried. Antihistamines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, and cytotoxics have been employed with variable success in moderate to severe cases. Small-vessel vasculitis with internal organ involvement requires aggressive immunosuppressive therapy. Drug rash, on the other hand, responds promptly to discontinuation of the offending medication as in this case.

In summary, we present a case of drug rash that mimicked leucocytoclastic vasculitis based on elevated acute-phase reactants and negative antinuclear antibodies. Diagnosis was established by histopathology and responded to avoidance of the drug.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Koutkia P, Mylonakis E, Rounds S, Erickson A. Cutaneous leucocytoclastic vasculitis associated with oxacillin. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;39:191–4.

- Bhattacharyya A, Yeddula K, Nwankwo N, Senussi MH. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.

- Koutkia P, Mylonakis E, Rounds S, Erickson A. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis: an update for the clinician. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:315–22.

- Khan DA. Cutaneous drug reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1225.