Abstract

Background. Inflammation may play an important role in type 2 diabetes. It has been proposed that dietary strategies can modulate inflammatory activity.

Methods. We investigated the effects of diet on inflammation in type 2 diabetes by comparing a traditional low-fat diet (LFD) with a low-carbohydrate diet (LCD). Patients with type 2 diabetes were randomized to follow either LFD aiming for 55–60 energy per cent (E%) from carbohydrates (n = 30) or LCD aiming for 20 E% from carbohydrates (n = 29). Plasma was collected at baseline and after 6 months. C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), IL-6, tumour necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) 1 and TNFR2 were determined.

Results. Both LFD and LCD led to similar reductions in body weight, while beneficial effects on glycaemic control were observed in the LCD group only. After 6 months, the levels of IL-1Ra and IL-6 were significantly lower in the LCD group than in the LFD group, 978 (664–1385) versus 1216 (974–1822) pg/mL and 2.15 (1.65–4.27) versus 3.39 (2.25–4.79) pg/mL, both P < 0.05.

Conclusions. To conclude, advice to follow LCD or LFD had similar effects on weight reduction while effects on inflammation differed. Only LCD was found significantly to improve the subclinical inflammatory state in type 2 diabetes.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01005498.

Key messages

In type 2 diabetes, randomization to advice to follow a low-carbohydrate diet or a low-fat diet had similar effects on weight reduction, while effects on inflammation differed.

After 6 months, the low-carbohydrate diet, but not the low-fat diet, had a favourable impact on low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

Inflammation is considered to play an important role in the development of type 2 diabetes as well as in further complications of the disease. At the cellular level, the expression of proinflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-1β and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) is implicated in insulin resistance and beta-cell failure (Citation1). An enhanced inflammatory activity is also detected in peripheral blood. It has been consistently shown in several clinical studies that the levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are increased in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with healthy individuals, thus indicating a low-grade systemic inflammation (Citation1–5). A few studies have also measured IL-1β and TNF in the circulation but with less consistent results (Citation3,Citation4,Citation6), probably due to the fact that circulating levels of IL-1β and TNF are often marginal. Instead, their major inhibitors, IL-1 receptor antagonist (Ra), TNFR1, and TNFR2, are readily secreted into the blood and considered reliable markers of activity of the cytokines (Citation7–9). Accordingly, elevated levels of IL-1Ra and TNFR2 in plasma have been associated with both insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (Citation10–12). Interestingly, IL-1Ra levels also predict the incidence of type 2 diabetes independently of CRP levels and other risk factors (Citation5,Citation13). Moreover, circulating levels of TNFR2 predict morbidities such as cardiovascular disease and nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes (Citation14,Citation15).

Lifestyle interventions play a crucial role in the management of type 2 diabetes and may also lead to reduced inflammation (Citation1,Citation16). The anti-inflammatory effects have been attributed mainly to the concomitant weight loss, whereas the effects of interventional strategies alone, e.g. dietary change, have been more difficult to verify. Traditionally, a low-fat diet has been the recommendation for achieving weight loss and improved glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. However, although still controversial, evidence is emerging that a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet has less favourable metabolic effects compared with a low-carbohydrate diet or Mediterranean diet in subjects at high cardiovascular risk (Citation17–22). Moreover, intake of carbohydrates, in particular refined carbohydrates, has been associated with a proinflammatory response (Citation23–25), whereas diets high in unsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids may decrease inflammation (Citation16,Citation22).

By using a randomized study design, our aim was to investigate the effects of diet on systemic inflammation in type 2 diabetes by comparing a low-fat diet (LFD) with a low-carbohydrate diet (LCD) during weight loss.

Material and methods

The study was performed in two primary health care centres in the south-eastern part of Sweden. The inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes treated with diet, with or without oral glucose-lowering medication or insulin. Exclusion criteria were difficulties in understanding the Swedish language, severe mental disease, malignant disease, or drug abuse. Patients were randomized to advice to follow either a traditional LFD (aiming for 30 energy per cent, E%, from fat) or an LCD (aiming for 20 E% from carbohydrates) over 2 years, as recently described (Citation20). Randomization was performed by drawing blinded ballots. The energy contents of diets were similar, 6694 kJ/day (1600 kcal/day) for women and 7531 kJ/day (1800 kcal/day) for men. Dietary advice was given by physicians on a group basis at baseline, 2, 6, and 12 months, and standardized in regard to energy content and nutrient composition. One dedicated dietician provided all participants with suitable recipes at each group meeting and was also available for questions from participants during the whole study period. Diet records from three consecutive days were performed at baseline, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Plasma samples were collected at baseline and 6 months, i.e. the time point when weight loss and compliance was maximal. Plasma samples were also collected from 41 control subjects in the same region, randomly invited from the Swedish Population Register. Subjects who accepted the invitation were included as controls if they were anamnestically healthy and received no medication. Anamnesis was gained by one dedicated nurse co-ordinator who also performed the blood sampling. None of the participants exhibited any clinical signs of acute inflammation at the time of blood collection. The research protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Linköping University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was registered with trial number NCT01005498 at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured using an immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Vienna, Austria) with a detection limit of 0.03 mg/L. IL-6 and TNFRs were measured in plasma by ELISA assays (RnD Systems Europe, Abingdon, United Kingdom) with detection limits of 0.48 pg/mL (IL-6), 0.8 pg/mL (TNFR1), and 0.6 pg/mL (TNFR2). TNF, IL-1β and IL-1Ra were analysed with Luminex (RnD Systems) with the detection limits 5.4, 2.8, and 7.9 pg/mL, respectively. Inter-assay coefficients of variation were 4.5%, 8.1%, 4.7%, 12%, and 11% for CRP, IL-6, TNFR1, TNFR2, and IL-1Ra, respectively.

IBM SPSS Statistics 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Differences within and between groups were analysed with Student's paired and unpaired two-tailed t test except for inflammatory markers that were not normally distributed. For CRP, IL-6, TNFR1, TNFR2, and IL-1Ra, Mann–Whitney U test was used for between-group comparisons differences and Wilcoxon signed ranks test for within-group comparisons. For correlation analyses Spearman's rank correlation was used. A linear multiple regression analysis was performed to assess the independent contribution of different factors to changes in cytokine levels. Effects on weight and HbA1c levels were the main outcome variables. The original statistical power calculation that has been previously described (Citation20) was based on an earlier 6-month pilot study of 28 participants with type 2 diabetes who were randomized to the same diets as in the present study. Twenty patients completed the study, and both diet groups achieved similar reductions in weight, while HbA1c levels tended to decrease in the LCD group only. Based on the results from the pilot study, the number of participants in the present trial was increased to at least 30 in each group.

Results

Study participants

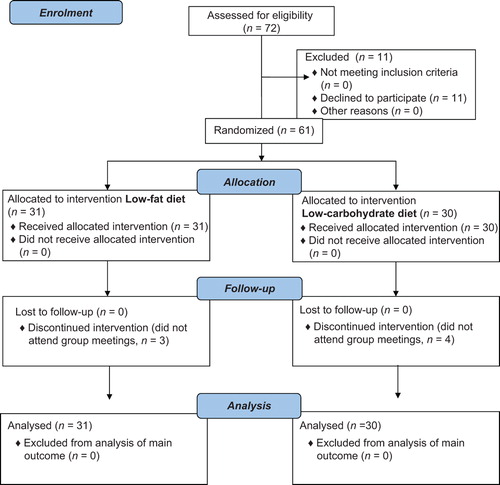

Seventy-two patients were consecutively invited by the study nurses to participate. As shown in the flow diagram (), 61 patients entered the study. No patients were lost to follow-up. Demographic and diabetes-related variables of patients in the two groups are presented in . None of the participants were smokers. At baseline, 24 (77%) LFD patients and 22 (73%) LCD patients were treated with cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins).

Table I. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the two intervention groups at baseline.

Effects on metabolic parameters

The results of dietary records are shown in . Adherence to the proposed diet was similar in both groups. However, the most prominent changes in nutrient intake were seen in the LCD group with a significant reduction in E% intake from carbohydrates and a concomitant increase in E% intake from fat. At 6 months, the E% intake from fat:carbohydrate was 29:49 in the LFD group and 49:25 in the LCD group. The levels of body mass index, HbA1c, lipid levels and insulin doses at baseline and after 6 months are shown in . Both groups showed a significant reduction in body mass index. Also, the reduction in absolute weight was similar between groups and maximal at 6 months: LFD −4.0 (4.1) kg, LCD −4.3 (3.6) kg. Although beneficial changes of HbA1c and HDL cholesterol levels were seen in the LCD group, the levels of HbA1c and HDL cholesterol remained similar between groups. After 6 months, the total insulin dose was significantly reduced in the LCD group but not in the LFD group, while the use of oral glucose-lowering medication did not change.

Table II. Dietary outcomes at baseline and 6 months in the two intervention groups (P values ≥ 0.10 are listed as non-significant, NS).

Table III. Values of body mass index (BMI), HbA1c, and lipids at baseline and 6 months in the two intervention groups.

Effects on inflammatory parameters

The levels of IL-1β and TNF were below the limits of detection in all participants. The levels of CRP, IL-1Ra, IL-6, TNFR1, and TNFR2 at baseline and after 6 months are presented in . At baseline, no differences were seen between the two groups. After 6 months, CRP levels did not show any significant changes within the groups. IL-1Ra levels, on the other hand, decreased significantly in the LCD group, while no change was seen in the LFD group. The levels of IL-6 increased in the LFD group only. After 6 months, both IL-1Ra and IL-6 levels were significantly lower in the LCD group than in the LFD group. TNFR1 levels did not change in any of the groups, while TNFR2 tended to increase in LFD patients (P = 0.064).

Table IV. Levels of inflammatory markers at baseline and 6 months in the two intervention groups.

During the study period, statin therapy was initiated in two LCD patients, and, hence, 24 patients in each group were treated with statins at 6 months. At baseline, the levels of CRP, IL-1Ra, IL-6, TNFR1, and TNFR2 did not differ significantly between statin users (n = 46) and non-statin users (n = 15), neither did changes in inflammatory markers differ between statin and non-statin users after 6 months. If the two LCD patients receiving statin during the study period were excluded from the analysis, the reduction of IL-1Ra remained significant in the LCD group (P = 0.002).

Correlations between baseline variables and between changes during intervention

All inflammatory markers were correlated with each other (P values of at least 0.01). Moreover, all inflammatory markers were significantly correlated with BMI (P values of at least 0.01). Levels of CRP, TNFR1, and TNFR2 showed correlations with insulin therapy as well as insulin dose (P < 0.05), while levels of IL-1Ra, TNFR1, and TNFR2 were correlated with HbA1c (P < 0.05). The change in IL-1Ra during intervention was correlated with changes in BMI (r = 0.302, P < 0.05), HbA1c (r = 0.411, P < 0.01), CRP (r = 0.245, P < 0.05), and IL-6 (r = 0.266, P < 0.05) but not with changes in energy intake, HDL cholesterol, or insulin dose. The change in IL-6 correlated with change in CRP (P < 0.05) but not with changes in energy intake, BMI, weight, HbA1c, HDL cholesterol, or insulin dose. In multiple regression analyses using change in IL-1Ra as dependent variable and changes in BMI, HbA1c, CRP, and IL-6 as independent variables, change in IL-1Ra remained associated with change in HbA1c only (standardized regression coefficient β = 0.365, P < 0.05).

Comparison with a population without known diabetes

Forty-one clinically healthy subjects, 24 men and 17 women, all non-smokers (age 64 (7.9) years, BMI 25 (3.2) kg/m2), were recruited as clinically healthy controls in order to provide ‘reference’ levels of systemic inflammatory markers. The levels in the controls were significantly lower compared with the baseline levels in patients: CRP 0.73 (0.32–1.19) mg/L, IL-1Ra 713 (1996–2502) ng/mL, P values of < 0.05, < 0.001, < 0.001, < 0.001, and < 0.05, respectively. In the LCD group, the levels of IL-1Ra and IL-6 were still significantly higher than in controls after 6 months, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, while CRP had reached levels that were similar to controls ().

Discussion

In the present study, we provide evidence that advice to follow a LCD reduces the subclinical proinflammatory state in type 2 diabetes. Despite similar weight loss and similar total energy intake in patients who were randomized to follow either LFD or LCD, cytokine levels were differently affected in the two groups. After 6 months, IL-1Ra showed a significant decrease in patients who were randomized to follow LCD, while IL-6 increased (and TNFR2 tended to increase) in those who followed LFD. Overall, these changes resulted in significantly lower levels of IL-1Ra and IL-6 in the LCD group compared with the LFD group at 6 months. Clinical studies investigating the effects of carbohydrate restriction on inflammation are sparse, but results that are in line with our findings have been reported. In one study, 40 overweight individuals with atherogenic dyslipidemia were randomized to ad libitum diets very low in carbohydrate (12%) or low in fat (24%) for 12 weeks. Both diets decreased the levels of inflammatory proteins, but overall the anti-inflammatory effect of carbohydrate restriction was larger in the very-low carbohydrate group than in the LFD group (Citation26). A recent study by Davis et al. (Citation27) compared LFD with LCD in 51 patients with type 2 diabetes and, in contrast to our results, did not find any differences in IL-6 after 6 months. On the other hand, these authors observed a decrease in soluble adhesion molecules, like E-selectin, in the LCD arm only. Anti-inflammatory effects of carbohydrate restriction have also been reported in animal models. Guinea pigs assigned to be fed LCD for 12 weeks showed significantly lower levels of inflammatory markers and oxidized cholesterol in the aorta compared with guinea pigs fed LFD (Citation28).

A carbohydrate-rich diet itself has also been associated with proinflammatory effects. A regimen of a 4-month eucaloric LFD in 22 healthy women resulted in unfavourable effects on inflammatory markers including CRP and IL-6 (Citation29). In the large PREDIMED Study, subjects at high cardiovascular risk were randomized to either two types of Mediterranean diet or a control diet (Citation21). The control diet group who received advice to follow a low-fat diet reported 44 E% intake from carbohydrates which is rather close to the carbohydrate intake in our LFD group (49 E%). In a minor sub-study of PREDIMED, the levels of IL-6 and soluble adhesion molecules decreased in the Mediterranean diet groups, while a significant increase was observed in the control group after 3 months (Citation30). In a larger sub-study of PREDIMED, the levels of IL-6, TNFR1, and TNFR2 decreased in the Mediterranean diet groups while TNFR1 and TNFR2 increased significantly and IL-6 trended upwards in the control group after 12 months, thus supporting that advice to reduce fat intake, and thereby increase carbohydrate intake, is associated with proinflammatory effects (Citation31). Notably, the PREDIMED Study showed a significantly higher incidence of both type 2 diabetes and major cardiovascular events in the control group compared with the Mediterranean diet group after a median follow-up of 4–5 years (Citation19,Citation21).

Several mechanistic studies have reported that acute exposure to carbohydrates induces a proinflammatory response (Citation1,Citation16). This effect is also more pronounced in subjects with obesity or impaired glucose tolerance (Citation32,Citation33). In obese patients presenting for bariatric surgery, a history of high carbohydrate intake was associated with significantly higher odds of inflammation in the liver, while higher fat intake was associated with less inflammation (Citation34). Also, the type of carbohydrate may have a major influence on inflammation. Both population-based and experimental studies have provided evidence that high intake of refined or simple carbohydrates is associated with proinflammatory effects (Citation23–25). In the LCD group of our study, the reduction in consumption of simple carbohydrates (monosaccharides, disaccharides, and saccharose) was more pronounced than the reduction in fibre consumption, thus allowing us to speculate that this might have contributed to the lower cytokine levels.

Not only the nature of carbohydrates but also the nature of dietary fats can modulate inflammation. Several studies have reported that a meal enriched in saturated fatty acids is followed by a proinflammatory response. On the other hand, diets high in unsaturated or polyunsaturated fatty acids have been associated with anti-inflammatory effects (Citation22,Citation30,Citation31). Based on dietary records, we found no changes in the proportional intake of saturated, unsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids in the LFD group over 6 months. In the LCD group, the percentage of energy intake from saturated fat showed a significant increase, but, concomitantly, similar increases in intake of unsaturated and polyunsaturated fat were seen.

The reduction of IL-1Ra levels in the LCD group constituted the most prominent change in inflammatory biomarkers. The reduction in IL-1Ra was also associated with a reduction in HbA1c after adjustment for weight reduction and changes in CRP and IL-6, indicating a close link between IL-1Ra and glycaemic control. In a previous study, Ruotsalainen et al. (Citation9) used a broad panel of cytokines in order to examine whether levels were abnormal in 129 offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. Interestingly, only the levels of IL-1Ra were elevated in normoglycaemic offspring and even more so in offspring with impaired glucose tolerance compared with healthy controls, suggesting that IL-1Ra is the most sensitive marker of cytokine response in the prediabetic state.

According to current guidelines, the majority of patients were treated with statins, which to some extent may affect the inflammatory response. In vitro, statins exert a wide variety of anti-inflammatory effects, and in randomized trials it is well documented that statins reduce plasma levels of CRP, whereas effects of cytokine levels are less evident (Citation35). We did not find any significant association between changes in inflammatory markers and statin therapy. However, it is still possible that diet-induced effects on CRP levels have been attenuated by the extensive use of statins in our study.

Advice to follow LFD or LCD had similar effects on weight reduction in our study. This is not in agreement with previous randomized studies reporting a greater weight loss with LCD than with LFD (Citation36). One explanation may be that our aim was to achieve similar energy restriction in the two groups in order to focus on the effects of macronutrient composition. Accordingly, both groups also reported similar energy intake during the study.

One limitation of our study is the limited sample size and possible impact of other lifestyle-related factors, which is a methodological problem in any nutritional intervention. The patients were also informed of randomization results before the diet record at baseline was performed. This may explain why the reported intake of fat and carbohydrates differed between groups at baseline. The participants may already have started to adjust their diets according to allocated diet. No participants were lost to follow-up, which is a strength of the study. The fact that study nurses in the two primary health care centres had been responsible for the care of the participants ahead of the study start may explain this remarkably high participation rate.

Efforts to reduce systemic inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes may be of utmost importance for the prevention of complications, such as cardiovascular disease and nephropathy. Carbohydrate restriction has been associated with anti-inflammatory effects, but, still, evidence is insufficient to support specific amounts of carbohydrate and fat intake in individuals with type 2 diabetes, as stated by American Diabetes Association in their recently published recommendations for dietary therapy (Citation37). Our findings, however, indicate that the use of LCD aiming for 20 E% intake from carbohydrates may be an effective strategy to improve the subclinical inflammatory state in type 2 diabetes.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kolb H, Mandrup-Poulsen T. An immune origin of type 2 diabetes?. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1038–50.

- Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286:327–34.

- Spranger J, Kroke A, Möhlig M, Hoffmann K, Bergmann MM, Ristow M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes. Results of the prospective population-based European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC). Potsdam Study. Diabetes. 2003;52:812–17.

- Pham MN, Hawa MI, Pfleger C, Roden M, Schernthaner G, Pozzilli P, et al. Pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines in latent autoimmune diabetes in adults, type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients: Action LADA 4. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1630–8.

- Luotola K, Pietilä A, Zeller T, Moilanen L, Kähönen M, Nieminen MS, et al. Associations between interleukin-1 (IL-1) gene variations or IL-1 receptor antagonist levels and the development of type 2 diabetes. J Intern Med. 2011;269:322–32.

- Plomgaard P, Nielsen AR, Fischer CP, Mortensen OH, Broholm C, Penkowa M, et al. Associations between insulin resistance and TNF-alpha in plasma, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue in humans with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2562–71.

- Aderka D. The potential biological and clinical significance of the soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7:231–40.

- Hurme M, Santtila S. IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) plasma levels are co-ordinately regulated by both IL-1Ra and IL-beta genes. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2598–602.

- Ruotsalainen E, Salmenniemi U, Vauhkonen I, Pihlajamäki J, Punnonen K, Kainulainen S, et al. Changes in inflammatory cytokines are related to impaired glucose tolerance in offspring of type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2714–20.

- Fernández-Real JM, Broch M, Ricart W, Casamitjana R, Gutierrez C, Vendrell J, et al. Plasma levels of the soluble fraction of tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1998;47:1757–62.

- Meier CA, Bobbioni E, Gabay C, Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F, Golay A, Dayer JM. IL-1 receptor antagonist serum levels are increased in human obesity: a possible link to the resistance to leptin?. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1184–8.

- Somm E, Cettour-Rose P, Asensio C, Charollais A, Klein M, Theander-Carrillo C, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist is upregulated during diet-induced obesity and regulates insulin sensitivity in rodents. Diabetologia. 2006;49:387–93.

- Herder C, Brunner EJ, Rathmann W, Strassburger K, Tabák AG, Schloot NC, et al. Elevated levels of the anti-inflammatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist precede the onset of type 2 diabetes: the Whitehall II Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:421–3.

- Shai I, Schulze MB, Manson JE, Rexrode KM, Stampfer MJ, Mantzoros C, et al. A prospective study of soluble tumor necrosis factor-a receptor II (sTNFRII) and risk of coronary heart disease among women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1376–82.

- Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Skupien J, Smiles AM, Walker WH, Rosetti F, et al. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:507–15.

- Kolb H, Manrup-Poulsen T. The global diabetes epidemic as a consequence of lifestyle-induced low-grade inflammation. Diabetologia. 2010;53:10–20.

- Volek JS, Phinney SD, Forsythe CE, Quann EE, Wood RJ, Puglisi MJ, et al. Carbohydrate restriction has a more favorable impact on the metabolic syndrome than a low fat diet. Lipids. 2009;44:297–309.

- Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, Makris AP, Rosenbaum DL, Brill C, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:147–57.

- Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M, Babio N, Martínez-González MÁ, Ibarrola-Jurado N, Basora J, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:14–19.

- Guldbrand H, Dizdar B, Bunjaku B, Lindström T, Bachrach-Lindström M, Fredrikson M, et al. In type 2 diabetes, randomisation to advice to follow a low-carbohydrate diet transiently improves glycaemic control compared with advice to follow a low-fat diet producing a similar weight loss. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2118–27.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas MI, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Eng J Med. 2013;368:1279–90.

- Esposito K, Marfella R, Ciotola M, Di Palo C, Giugliano F, Giugliano G, et al. Effect of a Mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1440–6.

- Jiu S, Manson JA, Buring JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Ridker PM. Relation between a diet with a high glycemic load and plasma concentrations of high-sensitive C-reactive protein in middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:492–8.

- Schulze MB, Hoffmann K, Manson JE, Willett WC, Meigs JB, Weikert C, et al. Dietary pattern, inflammation, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:675–84.

- Oliveira MC, Menezes-Garcia Z, Henriques MC, Soriani FM, Pinho V, Faria AM, et al. Acute and sustained inflammation and metabolic dysfunction induced by high refined carbohydrate-containing diet in mice. Obesity. 2013;21:E396–406.

- Forsythe CE, Phinney SD, Fernandez ML, Quann EE, Wood RJ, Bibus DM, et al. Comparison of low fat and low carbohydrate diets on circulating fatty acid composition and markers of inflammation. Lipids. 2008;43:65–77.

- Davis NJ, Crandall JP, Gajavelli S, Berman JW, Tomuta N, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Differential effects of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on inflammation and endothelial function in diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2011;25: 371–6.

- Leite JO, DeOgburn R, Ratliff J, Su R, Smyth JA, Volek JS, et al. Low-carbohydrate diets reduce lipid accumulation and arterial inflammation in guinea pigs fed a high-cholesterol diet. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209;442–8.

- Kasim-Karakas SE, Tsodikov A, Singh U, Jialal I. Responses to inflammatory markers to a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet: effects of energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:774–9.

- Mena MP, Sacanella E, Vazquez-Agell M, Morales M, Fito M, Escoda R, et al. Inhibition of circulating immune cell activation: a molecular antiinflammatory effect of the Mediterranean diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:248–56.

- Urpi-Sarda M, Casas R, Chiva-Blanch G, Romero-Mamani ES, Valderas-Martínez P, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. The Mediterranean diet pattern and its main components are associated with lower plasma concentrations of tumor necrosis factor receptor 60 in patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. J Nutr. 2012;142:1019–25.

- Ziccardi P, Nappo F, Giugliano G, Esposito K, Marfella R, Cioffi M, et al. Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation. 2002; 106:2067–72.

- Gonzalez F, Miium J, Rote NS, Kirwan JP. Altered tumor necrosis factor alpha release from mononuclear cells of obese reproductive-age women during hyperglycemia. Metabolism. 2006;55:271–6.

- Solga S, Alkhuraishe AR, Clark JM, Torbenson M, Greenwald A, Diehl AM, et al. Dietary composition and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1578–83.

- Devaraj S, Rogers J, Jialal I. Statins and biomarkers of inflammation. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2007;9:33–41.

- Ajala O, English P, Pinkney J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of different dietary approaches to the management of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:505–16.

- Evert AB, Boucher JL, Cypress M, Dunbar SA, Franz MJ, Mater-Davis EJ, et al. Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;37(Suppl 1): S120–43.