Abstract

Objective. To determine the efficacy of Advocacy and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy interventions (CBT) in reducing physical, psychological, sexual, or any intimate partner violence (IPV).

Methods. A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted using randomized control trials (RCTs) published in MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus, Cochrane, and Clinical trials. The occurrence of physical, psychological, sexual, and/or any IPV measured efficacy.

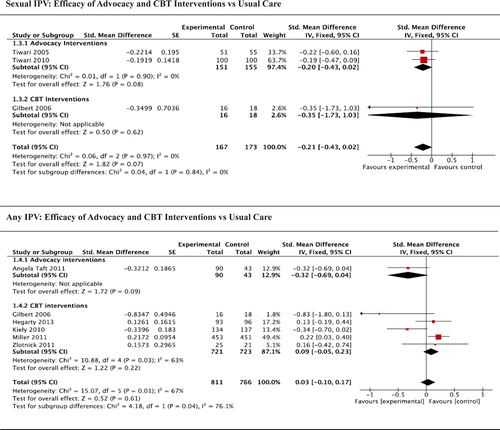

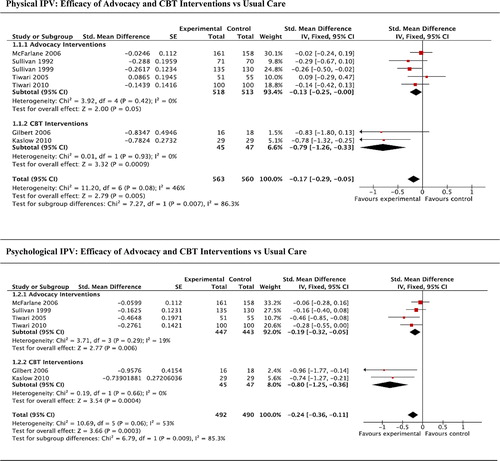

Results. Twelve RCTs involving 2666 participants were included. Advocacy interventions resulted in significant reductions in physical (standardized mean difference (SMD) –0.13; 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.25, –0.00) and psychological (SMD –0.19; 95% CI –0.32, –0.05) but not in sexual (SMD –0.20; 95% CI –0.43, 0.02) or any IPV (SMD –0.32; 95% CI –0.69, 0.04). CBT interventions showed a significant reduction in physical (SMD –0.79; 95% CI –1.26, –0.33) and psychological (SMD –0.80; 95% CI –1.25, –0.36) but not sexual (SMD –0.35; 95% CI –1.73, 1.03) or any IPV (SMD 0.09; 95% CI –0.05, 0.23).

Conclusions. Both advocacy and CBT interventions reduced physical and psychological IPV but not sexual or any IPV. Limitations include the low number of studies and the heterogeneity of interventions.

Key messages

Advocacy and cognitive behavioural therapy interventions reduced the occurrence of physical and psychological intimate partner violence for female victims.

Advocacy and cognitive behavioural therapy interventions did not reduce the occurrence of sexual intimate partner violence for female victims.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global public health problem. The World Health Organization's recent multi-country study found that almost 30% of women had experienced physical (defined as the use of physical force against the woman by her partner including: pushing, shoving, confinement, pinching, slapping, kicking, biting, strangling, etc.) and/or sexual violence (e.g. sexual coercion or forced to have/perform sexual activities) by their intimate partner (Citation1). Psychological IPV was defined as the use of threats by the intimate partner to hurt the woman or the use of verbal or non-verbal acts including: threats to harm, constant criticism, humiliating or belittling, threats to harm themselves, threats of abandonment, jealousy, intimidation, etc. Evidence on the prevalence of experiencing psychological abuse from their intimate partner, from the WHO multi-country study, ranged from 20% to 75% across countries. Furthermore, the proportion of women reporting one or more controlling behaviours by their partner varied from 21% in Japan to almost 90% in urban United Republic of Tanzania, making it difficult to provide a useful context for this type of violence due to the great variation across cultures where such behaviour may be more acceptable (Citation2). The potential consequences of being a victim of psychological IPV include mental health problems, substance use, and somatoform disorders (Citation1).

IPV is one of the leading contributors to the burden of disease among women (Citation3). IPV victimization impacts negatively on women's physical, mental, sexual, reproductive health and quality of life (Citation4–7). Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse are associated with IPV victimization (Citation8–10), with evidence suggesting IPV victimization is associated with the onset of developing these disorders (Citation11). Victims of IPV have higher health and social care services utilization and costs than non-victims (Citation12). The annual health care costs for women experiencing IPV have been reported to be 42% higher compared to women without IPV and can persist as long as 15 years after the cessation of IPV (Citation12,Citation13). Therefore, it is important to identify and address IPV victimization early to improve health outcomes for victims and reduce health care costs.

Previous systematic reviews of interventions to reduce frequency of IPV among female victims have been undertaken (Citation8,Citation9,Citation14–17). Only two systematic reviews included meta-analyses (Citation15,Citation17), and only three were based on randomized controlled trials (Citation14,Citation15,Citation17). These reviews have examined advocacy, batterer and couple interventions (Citation8); individual and couples-based addiction and IPV treatments (Citation9); treatment programmes for IPV perpetrators, victims, or child witnesses (Citation14); advocacy interventions only (Citation15); interventions to reduce IPV among pregnant women (Citation16,Citation17); and one included mixed interventions (advocacy and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)) (Citation17). Although advocacy and CBT interventions are the most commonly used interventions, none of the previous reviews examined their efficacy by the type of IPV experienced, nor compared the efficacy of advocacy and CBT interventions. Advocacy interventions included support provided by advocates and mentor mothers aiming to enhance female victim safety such as information, provision of legal support, housing and financial advice, and telephone social support, developing safety planning and facilitating access to community resources, without any psychotherapeutic approach. CBT interventions included a wide range of individual and group interventions that used cognitive and behavioural components, motivational interviewing, and/or problem-solving techniques to provide emotional, communication, and assertiveness skills to manage IPV and other co-morbid mental health problems and its symptomatology, delivered by health care providers. These definitions incorporate the WHO intervention descriptions as well as those provided by the authors of the interventions from the trials included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

The most recent published review on advocacy interventions was in 2009 (Citation15), and the recent World Health Organization clinical guidelines based on systematic reviews did not look at these two interventions separately for an effect on IPV (Citation18). Therefore, there remains a need to 1) update the evidence; 2) review the efficacy of different types of randomized control trial (RCT) interventions to reduce IPV victimization; and 3) determine the efficacy of these interventions (advocacy and CBT) in reducing different types of IPV experienced (physical, psychological, sexual, and any IPV). A greater awareness of the most efficacious interventions for IPV would allow practitioners to select and deliver the best interventions, or make appropriate referrals when needed.

This review and meta-analysis focused on females experiencing IPV as women are more likely to be victims of IPV, suffering more severe IPV, and more likely to be murdered by their intimate partner in comparison to men (Citation18). Moreover, evidence for psychoeducational batterer (Citation19,Citation20) and CBT interventions (Citation21) for IPV victimization has produced inconclusive results and small effect sizes. Therefore, detecting and responding to IPV victimization may be more beneficial than addressing IPV perpetration. This review seeks to present and compare the effectiveness of existing options to address IPV victimization.

The aim of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the efficacy of advocacy and CBT interventions independently in reducing physical, psychological, sexual, and any IPV among female victims in comparison to usual care.

Methods

The review was undertaken in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations (Citation22).

Search strategy

MEDLINE (1990 to 30 April 2013), PsycINFO (1990 to 30 April 2013), Scopus (1989 to 2014), the Cochrane Collaboration (1990 to 30 April 2013), and Clinical trials (1990 to 30 April 2013) databases were searched using a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in MEDLINE, topics and key words in PsycINFO and Scopus for IPV interventions and randomized control trials. describes the search strategy employed and the different terms searched based on the thesaurus for each database. In addition, a review of relevant RCTs and backward and forward searching of citations was conducted. Citations were included regardless of language and country of origin. Little was known about the effectiveness of interventions for IPV victims before 1990. Previous reviews suggest that all evidence regarding interventions to address IPV victimization was post 1990, therefore it was decided to include RCTs from 1990 onwards.

Table I. Description of search terms.

For the purpose of this review, those interventions that included both advocacy and safety planning as their goal were grouped as ‘advocacy interventions’ if the intervention did not include any psychotherapeutic approach that used cognitive and behavioural components. IPV victimization was an additional variable measured in some of the included studies where CBT techniques focused not only on addressing IPV. When interventions included both CBT and advocacy, the interventions were grouped as ‘CBT’. For this review we defined ‘usual care’ as that care typically provided at that setting or usual care with minimal additions such as an information card or leaflet listing the addresses and telephone numbers of local support agencies.

Authors were consulted for clarification when it was not clear from the description of the intervention in the publication whether the intervention was based on CBT techniques, or when data provided in the paper were insufficient to allow calculations to be undertaken. Where data were not available or not provided by authors, studies were not included in the meta-analysis. Therefore, only 12 manuscripts were included in the meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria

Trials were eligible for inclusion if 1) they were randomized controlled trials or cluster randomized trials, 2) the outcome was the frequency or occurrence of IPV, and 3) they compared advocacy or CBT interventions to usual care. Screening interventions only and interventions delivered at home for domestic violence (mothers and children) were excluded.

Data extraction

Authors J.T.M. and G.G. independently assessed all articles against these eligibility criteria. Where there was disagreement, the decision whether to include or exclude each trial was reached through discussion with M.T. and K.H. Authors J.T.M. and G.G. independently extracted the following information using a standardized form: publication year, setting, per-group sample size (numbers recruited, numbers analysed), study and control interventions (brief descriptions including frequency and duration; outcomes assessed, length of follow-up and assessments used; and effects of the interventions) ().

Assessment of methodological quality

Two authors (J.T.M. and G.G.) independently assessed the methodological quality of the trials included in the review using the Risk of Bias tool (Citation23) for reporting randomized controlled trials. Differences in responses on the Risk of Bias tool were resolved through discussion with authors M.T. and M.F. and resolved by consensus without further analysis of Cohen's kappa. The Risk of Bias tool produces a quality interpretation with ratings of ‘Yes’ (low risk of bias), ‘No’ (high risk of bias), and ‘Unclear’ (uncertain risk of bias) for six key domains: 1) Sequence generation, 2) Allocation concealment, 3) Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors, 4) Incomplete outcome data, 5) Selective outcome reporting, and 6) Other sources of bias. The evaluation ranged from low-risk to high-risk methodology, with low risk equating to higher methodological quality. Only domain 1 was used as a criterion for inclusion in the current review; all other domains were considered to assess methodological quality of included studies. We included studies that were not described as single-blinded.

Main and subgroup analysis

RCTs where advocacy interventions were compared to control conditions were analysed separately from those where CBT were compared to control conditions. The occurrence of physical, psychological, sexual, and/or any IPV at follow-up was used to measure efficacy. When studies showed physical IPV disaggregated by violent acts, the highest violent act frequency score for evaluating physical IPV outcome was used. For those studies that were not disaggregated by types of violence, the measure ‘any IPV’ was used to measure efficacy. When the outcome was disaggregated to severe or minor violence, severe data were used (frequency score). Indicators for the four types of IPV (physical, psychological, sexual, any IPV) were provided by the authors directly from the manuscript, usually summing the single items for each type of violence (subscales). None of the trials included in the meta-analysis had more than one intervention group.

Statistical analysis

The principal summary measure was the standardized mean difference (SMD). For each RCT, the SMD and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the assessed outcome were retrieved or calculated. Data entry and statistical analysis were performed with the use of Review Manager software, version 5.0. (Citation24). As the outcome data were presented in some studies as dichotomous data and in others as continuous data, odds ratios were recalculated as standardized mean differences (SMD), allowing dichotomous and continuous data to be pooled together (Citation25). The standard errors of the log odds ratios were converted to standard errors of a standardized mean difference by multiplying by the same constant (√3/π = 0.5513). This allowed the standard error for the log odds ratio and hence a confidence interval to be calculated (Citation26). When data from more than one follow-up period were reported, data from the latest follow-up period were included in the meta-analysis, combining outcomes assessed at multiple time periods. As this could be considered one of the factors affecting the evaluation of efficacy, additional meta-analyses were conducted () grouping by similar follow-up points (from ‘up to six months’ to ‘over six months follow-up’). Similarly, due to the clinical heterogeneity of the interventions included, extra analyses were conducted, where possible, to assess if the duration of the intervention (from ‘up to five sessions’ to ‘over five sessions’) increased the efficacy of the interventions.

Results

The search resulted in 1585 citations (). A total of 1507 abstracts were excluded at the screening stage as they did not include interventions to reduce IPV victimization among adult females. Rather they included interventions that addressed IPV perpetration, sexual abuse in childhood, anger management, Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and relapse prevention; interventions for couples; not CBT interventions; pharmacological trials; IPV screening studies and descriptive studies. The remaining 78 abstracts were selected for assessment and read in full-text. After removing 22 duplicate references, 33 of the remaining 56 studies were excluded because IPV frequency or occurrence was not assessed or presented at follow-up (n = 23) (Citation27–49), they were not RCTs (n = 7) (Citation50–56), or they evaluated a home visiting (mothers and children) intervention (n = 3) (Citation57–59).

Figure 1. Flow chart for the selection of eligible studies. IPV = intimate partner violence; RCT = randomized control trial; IG = intervention group; CG: control group. *Three trials reported four manuscripts.

Altogether 23 manuscripts were included from 19 RCTs. One advocacy manuscript reported additional outcomes (safety-promoting behaviours and utilization of health services) (Citation60) from the same female sample (Citation61). Tiwari et al. (Citation61) was included in the meta-analysis. Three CBT manuscripts reported three different analyses from the same female sample (Citation62–64), with Kiely et al. (Citation64) being the most focused on IPV; and two manuscripts reported outcomes from the same sample but using different follow-up time-frames: 10 weeks (Citation65) and six months (Citation66) post intervention. Of the 19 RCTs included, eight were of advocacy (Citation61,Citation65,Citation67–72), and 11 were of CBT interventions (Citation64,Citation73–82). Six advocacy (Citation61,Citation65,Citation68,Citation70–72) and six CBT studies (Citation64,Citation75,Citation77–79,Citation82) were included in the meta-analysis.

The characteristics of the manuscripts are described in . Of the 19 RCTs, 14 were conducted in the USA (Citation64,Citation65, Citation67–69,Citation71,Citation73–80), two (Citation61,Citation70) in China, two in Australia (Citation72,Citation82), and one in Mongolia (Citation81). Recruitment setting of the included studies is described in . A total of 5400 women, mean age 30.6 years old (range 20–48 years) were recruited; 31% of participants were Afro-American, 16% were white non-Hispanic, 15% were Hispanic, 10% were black, 6% were Chinese, 5% were Australian, 3% were Mongolian, and 12% were classified as ‘other’, e.g. European American, Asian American, and other ethnicities not specified. Only one RCT included female drug users in the sample (Citation75), and women were recruited to six RCTs during pregnancy (Citation64,Citation69,Citation70,Citation72,Citation78,Citation79). A total of 896 participants received an advocacy intervention, and 2090 received a CBT intervention.

Quality and publication bias assessment

A summary of authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study is described in . Only six key domains were assessed as it was not feasible to blind participants or those delivering advocacy or CBT interventions. Six of the 19 trials satisfied at least four of the six risk-of-bias criteria, the rest fulfilled three or fewer (Citation64,Citation65,Citation67,Citation69,Citation71–73,Citation75,Citation76,Citation78,Citation79–81). Four studies satisfied all of the criteria (Citation61,Citation70,Citation74,Citation82). Information regarding allocation sequence generation and allocation concealment is described in . No trials were double-blinded, but in eight trials the evaluators were blind to group allocation (Citation61,Citation70,Citation73–75,Citation77,Citation80,Citation81). Three studies used survey or telephone interventions to assess outcomes (Citation64,Citation78,Citation82), and three trials reported that the outcome assessors were different to the person providing the intervention (Citation65,Citation68,Citation76). Four studies mentioned they were not single-blinded or did not give any explicit information about blinding (Citation67,Citation71,Citation72,Citation79). Eight RCTs (Citation61,Citation68,Citation70–72,Citation74,Citation77,Citation82) reported data on drop-outs. An intention-to-treat analysis was used in 11 trials (Citation64,Citation70,Citation72–74,Citation76–78,Citation80–82), although in some cases many fewer patients were analysed than were enrolled and randomized. There was no selective reporting bias by investigators, with all outcome measures described in the methods reported in the results. The sample of women in Kiely et al. (Citation64) reported more than one health risk factor (from IPV, depression, and passive and active smoking) at baseline and received more than one intervention to address their multiple needs. Therefore, it is not clear how many women received more than one intervention, and as a result there may be an interactive effect from receiving more than one intervention. In one study the same research nurses provided the intervention and the care of the control group (Citation71), and one study showed insufficient statistical power—groups did not differ statistically across the variables studied (Citation75). One RCT (Citation78) measured IPV in all women, not only those who reported experiencing it in the last three months at baseline. No other biases were detected. In all of the trials, participants’ characteristics were similar between intervention and control groups at baseline. Only four trials found one significant difference between groups at baseline (Citation61,Citation72,Citation74,Citation81). The three cluster randomized trials (Citation72,Citation78,Citation82) were also assessed using the domains for assessing risk of bias in cluster-randomized trials. No recruitment biases were found. Baseline differences were reduced by using stratified or pair-matched randomization of clusters in two RCTs (Citation72,Citation82). A low risk analysis was considered in two RCTs (Citation72,Citation82), and comparability with individually randomized trials was accepted by authors.

Table III. Risk of bias summary of advocacy and CBT interventions: review of authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. + (Green): yes (low risk of bias), ? (Yellow): unclear, − (Red): No (high risk of bias).

Qualitative analysis

Advocacy interventions

All advocacy interventions were delivered on an individual basis and compared with usual care. Substantial heterogeneity was found in the intensity of advocacy interventions included and populations varied in the meta-analysis, but all interventions were similar and based on the same approach. Two RCTs tested interventions of less than five sessions (Citation70,Citation71), while five trials tested interventions over five sessions (Citation61,Citation65,Citation67,Citation68,Citation72) with intervention duration ranging from 10 weeks (Citation65,Citation67,Citation68) to 12 months (Citation72). Three separate trials, conducted among women in domestic violence shelters (Citation65,Citation67,Citation68), compared the same intervention (10-week intensive one-to-one advocate service) to standard domestic violence shelter services (usual care), developing a safety plan and accessing community resources on leaving the shelter. Women were followed up for 10 weeks (Citation65), 6 months (Citation66), and 12, 18, and 24 months (Citation68) after leaving the shelter. One trial (Citation60,Citation61) compared the same advocacy intervention to usual community services including child care, health care and promotion, and recreational programmes. Three trials (Citation69,Citation70,Citation72) were conducted among pregnant women. Three trials compared an empowerment intervention to usual care (Citation69–71). Finally, one RCT (Citation72) compared a 12-month mentor mother advocacy intervention to clinician's care. Advocates did not deliver the intervention in four trials (Citation69–72).

CBT interventions

Eight CBT interventions were delivered on a one-to-one basis (Citation62–64,Citation76,Citation78–80,Citation82), and five were group interventions (Citation73–75,Citation77,Citation81). Four trials assessed interventions of up to five CBT sessions (Citation64,Citation78,Citation79,Citation82), and seven interventions consisted of interventions with more than five sessions (Citation73–77,Citation80,Citation81). Three trials tested an intervention designed to reduce HIV/sexually transmitted disease (STD), also addressing IPV (Citation73,Citation76,Citation81). One study tested the efficacy of an intervention aimed at enhancement of social support in a sample of pregnant women with recent IPV (Citation79) as social support has been found to be protective against the negative effect of IPV and women's mental health. A CBT for PTSD in women in domestic violence shelters (Citation80) was tested. The only trial conducted among female drug users tested a drug relapse prevention and relationship safety intervention to promote relationship safety and reduce drug use (Citation75). One trial assessed the efficacy of an intervention for psychological symptoms associated with IPV, such as suicidality (Citation77). Two more trials among pregnant women (Citation64) used a CBT intervention focusing on four risk factors (IPV, depression, and passive and active smoking), while one trial conducted among pregnant women (Citation78) focused on reproductive coercion and IPV education. Rychtarik et al. (Citation74) tested a coping skills training for women to conceptualize their distress from problematic drinking-related situations, offering problem-solving skills. The final RCT assessed a brief counselling after an IPV screening to increase women's quality of life, safety, mental health, and reduce IPV victimization (Citation82). Interventions were delivered by female facilitators (Citation73,Citation81), social workers (Citation64), family planning counsellors (Citation78), psychologists, therapists (Citation74,Citation75,Citation77,Citation79,Citation80), general practitioners (Citation82), and county health department staff (Citation76).

Assessed outcomes and evidence synthesis

There was variation in the length of time participants were followed up post intervention or post partum across trials, ranging from immediately post intervention (Citation67) to 24 months (Citation68) for advocacy. For CBT interventions this ranged from end of intervention (Citation77,Citation80) to 12 months post intervention (Citation73,Citation74,Citation77,Citation82). Various scales, subscales, and single questions were employed to measure IPV.

Physical IPV was the most frequent type of IPV assessed. All RCTs assessed this type of violence. A total of 13 trials (Citation61,Citation64,Citation65,Citation67,Citation68,Citation70,Citation74–76,Citation78–81) used various versions of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Citation83). Possible scores range from 0 to 6 for each of the Conflict Tactics subscales (physical assault, injury, psychological aggression, sexual coercion, negotiation), with higher scores indicating higher levels of IPV. One trial (Citation73) assessed physical IPV at baseline asking if women had ever been hit by a man with whom they had had a sexual relationship, and when this occurred. At each follow-up interview, participants were asked whether they had been hit by a partner since the last interview. Kaslow et al. (Citation77) assessed physical and non-physical IPV using the Index of Spouse Abuse (Citation84). McFarlane et al. (Citation69,Citation71) assessed physical IPV using the Severity of Violence Against Women Scale (SVAWS) (Citation85). Two trials (Citation72,Citation82) assessed IPV using the Composite Abuse Scale (Citation86). Data from five trials of CBT interventions (Citation73,Citation74,Citation76,Citation80,Citation81) could not be included in the meta-analysis due to the lack of available data for comparison (the means and/or standard deviations were not reported in the manuscript, and the authors were not able to supply these data). Therefore, the meta-analysis with physical IPV as the outcome included five trials of 518 randomized patients receiving advocacy (Citation61,Citation65,Citation68,Citation70,Citation71) and two trials of 45 participants receiving CBT interventions (Citation75,Citation77). Some trials reported data of this outcome disaggregated by violent acts, the higher violent act score being used to report this type of violence (Citation65,Citation66). One study reported the outcome disaggregated into severe or minor IPV; data for severe IPV were used (Citation75).

Psychological IPV was assessed in 14 RCTs (Citation61,Citation65,Citation68–72,Citation75–77,Citation79–82) using the Conflict Tactics Scale (Citation61,Citation70,Citation75,Citation76,Citation79–81), the Index of Psychological Abuse (Citation65,Citation68), the SVAWS (Citation69,Citation71), the Index of Spouse Abuse (Citation77), and the Composite Abuse Scale (Citation72,Citation82). Six trials were included in the meta-analysis where the occurrence of psychological IPV was the outcome: four trials were conducted among 447 randomized participants receiving advocacy (Citation61,Citation68,Citation70,Citation71) and two trials of CBT interventions among 45 participants (Citation75,Citation77). Studies reported this type of violence as emotional violence, psychological, threats, or non-physical outcome.

Sexual IPV was the least frequent outcome assessed, with 11 trials (Citation61,Citation64,Citation70,Citation72,Citation75,Citation76,Citation78–82) assessing it using the Conflict Tactics Scale (Citation61,Citation64,Citation70,Citation75,Citation76,Citation79–81), the Composite Abuse Scale (Citation72,Citation82), and the Sexual Experiences Survey (Citation78). Although trials assessed this type of violence using subscales, not all of them reported the outcome in this manner. Three trials were included in the meta-analysis where the frequency or occurrence of sexual IPV was the outcome: two trials of advocacy among 151 participants (Citation61,Citation70) and one trial of a CBT intervention among 16 participants (Citation75).

Any IPV was reported in some trials when IPV was not disaggregated by type of violence, combining physical and sexual (Citation64,Citation75,Citation78), or presenting means and SD of the total score (Citation72,Citation79,Citation82). Six trials were included in the meta-analysis where the occurrence of any IPV was the outcome (Citation64,Citation72,Citation75,Citation78,Citation79,Citation82)—one trial of advocacy among 90 participants (Citation72), and five trials of a CBT intervention among 721 participants (Citation64,Citation75,Citation78,Citation79,Citation82).

Physical IPV results

Participants allocated to receive advocacy showed a significant reduction in the occurrence of physical IPV compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.13; 95% CI –0.25, –0.00) (). Those receiving CBT interventions (only two RCTs were included, and the significance should be considered with caution given the small effect size) showed a significant reduction in physical IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.79; 95% CI –1.26, –0.33) (). Analysed together, both interventions showed a significant reduction in physical IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.17; 95% CI –0.29, –0.05) (). For advocacy, Sullivan and Bybee's paper (Citation68) was the major contributor to this outcome with 265 IPV victims. For CBT interventions, Gilbert et al. (Citation75) was the major contributor to this outcome, with 34 IPV victims.

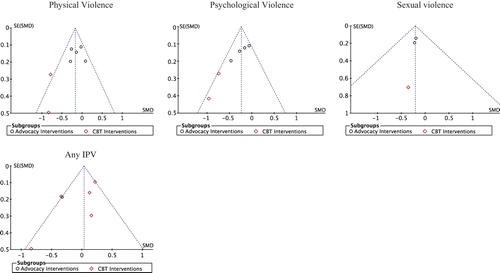

Figure 2. Physical, psychological, sexual, and any IPV: efficacy of advocacy and CBT interventions versus usual care. Weights are from fixed effects analysis. CI = confidence interval; SMD = standard mean differences.

Two potential factors that could have contributed to the efficacy of the interventions were studied—the different follow-up periods compared across trials and the heterogeneity of the interventions. Additional factors that may have contributed to the efficacy of the interventions were who delivered the intervention and the level of training or qualification of that professional. However, the manuscripts confirm that all CBT intervention facilitators were trained to provide the intervention and two CBT interventions were digitally recorded (Citation75,Citation77). For CBT interventions, the wide diversity of professionals delivering the interventions did not allow for the comparison of grouping by type of professional to determine whether the qualifications of those delivering the intervention could affect the evaluation of efficacy. Advocacy interventions were delivered by advocates with the exception of four studies (Citation69–72); only three of them were included in the meta-analysis (Citation70–72), and as a result a comparison was not possible. Experience of IPV was the eligibility criteria for inclusion in all trials included in the meta-analysis, with one exception (Citation78). The wide variety of settings (primary care, prenatal clinic, community centres, drug dependence centres, and shelters) for recruitment and delivery of the interventions and the small numbers of studies from each setting included in the meta-analysis did not allow the evaluation of efficacy to be considered by intervention setting. Future research should address the impact of intervention setting. A comparison was conducted of those interventions assessed of up to six months and over six months follow-up. Those receiving advocacy interventions showed a non-significant reduction in physical IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care, grouping by follow-up (). Those receiving CBT interventions showed a significant reduction in physical IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care, grouping by follow-up, although only one study was included where participants were followed up for over six months (). Comparing outcomes assessed at different follow-up periods did not impact on the efficacy of advocacy interventions; however, it may have impacted on CBT interventions. Regarding intensity of the interventions compared, interventions were grouped into those with up to five sessions and those with more than five sessions. For advocacy interventions, the intensity of the interventions may have affected efficacy, but this cannot be confirmed without the q statistic (). Advocacy interventions with more than five sessions were more effective (). All CBT interventions included in the meta-analysis for this type of violence had more than five sessions (). The heterogeneity was 46% and considered moderate, therefore no further analysis of the heterogeneity was conducted. Despite the low number of trials included, funnel plots of the efficacy outcome IPV were produced (). Physical IPV showed a tendency towards symmetry discharging reporting biases. Larger trials, mostly advocacy interventions, are distributed at the top of the funnel plot.

Table IV. Efficacy of advocacy and CBT interventions versus usual care grouping by follow-ups and intensity of interventions.

Psychological IPV results

Participants allocated to receive advocacy intervention showed a significant reduction in psychological IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.19; 95% CI –0.32, –0.05) (). Those receiving CBT interventions (only two RCTs were included) showed a significant reduction in psychological IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.80; 95% CI –1.25, –0.36) (). Analysed together both types of interventions showed a significant reduction in psychological IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.24; 95% CI –0.36, –0.11) (). Tiwari et al. (Citation70) was the major contributor to this outcome with 106 IPV victims for advocacy, and Gilbert et al. (Citation75) was the major contributor to this outcome for CBT interventions with 34 IPV victims.

We also compared outcomes for these interventions at up to six months follow-up and over six months follow-up. Comparing outcomes assessed at different follow-up periods did not appear to impact on the efficacy of advocacy interventions, but it did impact on the efficacy of CBT interventions (). All advocacy interventions (up to five and over five sessions) showed a reduction in psychological IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care (). All CBT interventions included in the meta-analysis for this type of violence consisted of more than five sessions (). The heterogeneity of 53% reported could be considered moderate. No further analysis of the heterogeneity was conducted. A tendency towards asymmetric funnel plots was found but, given the low number of trials, it was not possible to confirm this ().

Sexual IPV results

Participants allocated to receive advocacy showed a non- significant reduction in sexual IPV occurrence, compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.20; 95% CI –0.43, 0.02) (). Those receiving CBT interventions (only one study) showed a non-significant reduction in sexual IPV occurrence, compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.35; 95% CI –1.73, 1.03) (). One possible explanation for the non-significance of the outcomes for this type of violence could be the low number of trials included and the variability of the results (i.e. wide confidence intervals). Comparisons of the length of follow-up and intensity of the interventions could not be estimated due to the lack of studies for grouping. The low number of trials did not allow conclusions about publication bias to be made ().

Any IPV results

Only one advocacy trial reported data in this manner. Participants allocated to receive advocacy intervention showed a non-significant reduction in the occurrence of any IPV compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD –0.32; 95% CI –0.69, –0.04) (). Five CBT trials reported occurrence of IPV in this manner. Those receiving CBT interventions showed a non-significant reduction in any IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD 0.09; 95% CI –0.05, 0.23) (). Analysed together, both interventions showed a non-significant reduction in any IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care (SMD 0.03; 95% CI –0.10, 0.17) (). For CBT interventions, Gilbert et al. (Citation75) was the major contributor to this outcome, with 34 IPV victims.

It was not possible to compare outcomes for advocacy trials by length of follow-up due to the lack of included studies for this outcome. Those receiving CBT interventions showed a non-significant reduction in any IPV occurrence compared to those allocated to usual care at up to six months follow-up. Outcomes for over six months follow-up could not be assessed due to the lack of studies for grouping (). Comparing outcomes assessed by duration of follow-up does not appear to affect the efficacy of CBT interventions (). No advocacy trials could be assessed for the intensity of the intervention. All CBT interventions contained up to five sessions, with one exception (Citation75), and it seems there was no difference found when interventions with up to five sessions were grouped (). An increased heterogeneity was found (67%) for this outcome. Any IPV showed a tendency towards symmetry discarding reporting biases (). Despite this, the small numbers of trials included did not allow firm conclusions to be drawn regarding whether publication biases existed.

Discussion

Summary of key evidence

This is the first meta-analysis to consider the efficacy of advocacy and CBT interventions independently in reducing the occurrence of IPV, and it is the first to discriminate the type of intervention indicated for each type of IPV experienced (physical, psychological, sexual, and any IPV). Nineteen RCTs were identified; however, only six RCTs of advocacy and six RCTs of CBT interventions were included in the meta-analysis. The current evidence suggests that both advocacy and CBT interventions may be significantly more efficacious in reducing physical and psychological IPV than usual care. The small effect size and the heterogeneity of interventions do not allow us to draw firm conclusions. Sexual IPV was not reduced by either advocacy or CBT interventions in the few studies included in our review for this outcome.

These findings serve to update previous systematic reviews (Citation15) and try to report an evidence base on the effectiveness of CBT interventions that was previously unknown, enhancing our understanding of what works to reduce specific types of IPV victimization. A different number of studies were included in our review compared to a previous review on advocacy interventions (Citation15). This is due to the fact that we excluded interventions focused on mothers and children. Due to the low number of studies included in the meta-analysis, the results should be interpreted with caution. Therefore, while the current evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of CBT interventions in reducing or eliminating IPV, some recommendations and implications for future research can be made. One previous meta-analysis conducted in 2009 evaluated the effectiveness of advocacy interventions (Citation15). Our findings are consistent with that meta-analysis (Citation15), which also found that advocacy was effective for women who actively sought help. The current meta-analysis adds to these findings by confirming that intensive advocacy interventions were effective in reducing physical IPV, but evidence is equivocal regarding psychological and sexual IPV. While screening ‘asymptomatic individuals’ for IPV does not improve the health status of those screened, there remains a need for more evidence regarding the types of intervention that may be effective in specific settings (Citation87).

Psychological IPV is frequently reported as part of violent intimate relationships, and it has been found to affect negatively women's health as significantly as the other types of IPV (Citation88). Our findings show that CBT interventions were effective for physical and psychological IPV but were not found to be effective when the outcome was any IPV victimization. The CBT studies that assessed psychological IPV showed encouraging results in reducing this type of violence, but the small number of studies (only two) needs to be considered. CBT interventions aim to provide the necessary skills (e.g. cognitive restructuring, motivational interviewing techniques, thought-stopping, coping skills, problem-solving, etc.) to protect IPV victims from further psychological IPV. Whilst women are in still in relationships where IPV is happening, counselling interventions may increase women's perceived support and comfort to discuss abuse with trusted others. This in turn may lead to positive changes in women's readiness to take some action and their own self-efficacy, and these ‘internal’ changes may collectively lead to increases in safety behaviours and improvement in women's mental health (Citation89). Furthermore, CBT interventions are recommended for women who are no longer experiencing violence (Citation18). It may be that these CBT skills assist women to re-evaluate their relationships and that this in turn changes the dynamic of psychological abuse. Furthermore, CBT interventions may also be effective for physical IPV when disaggregated by types of violence. CBT interventions varied between integrated approaches where at least two health topics were addressed (HIV/IPV prevention intervention; relationship safety and relapse prevention; cigarette exposure, prenatal outcomes, and IPV; PTSD and IPV) and those that focused on IPV only. The use of mental health interventions with women experiencing IPV is supported by this meta-analysis and by research suggesting that PTSD symptoms among IPV victims are associated with an increased risk of re-abuse (Citation90). Moreover, the recent WHO guidelines recommend CBT interventions for women who are experiencing PTSD and have experienced IPV in the past (Citation7). The findings by Johnson et al. (Citation80) advocate that integrated interventions for PTSD and IPV may be a promising treatment for recent IPV victims living in shelters. The research question here implies CBT would be provided to reduce abuse primarily or its effect on mood or PTSD symptoms. Future research should answer this question assessing outcomes other than IPV occurrence, to understand whether the reduction in IPV victimization is the effect of recovery in other domains such as mental health symptoms and/or quality of life. However, the efficacy of advocacy interventions, which reduced both physical and psychological IPV, was also supported by our analyses. Our findings suggest that a combination of both types of intervention should be considered to enhance outcomes for IPV victims. The World Health Organization's recent clinical guidelines recommend aspects of advocacy and cognitive behaviour therapy. While IPV is not a medical disorder, it is a relevant topic for medical professionals who may assist women experiencing IPV victimization within their practice, primary care being a setting for early intervention in IPV (Citation2). Lifetime rates of IPV victimization in women attending general practice range from 21% to 53% (Citation91); from 1.0% to 20% (Citation17) during pregnancy; and the prevalence of physical abuse among female drug users ranges from 25% to 57% (Citation75). The findings from this systematic review and meta-analysis could help them be more aware of available interventions and the efficacy of interventions and, therefore, make appropriate referrals. An increased understanding is crucial to assist professionals to provide appropriate assistance in terms of screening, assessment, offering support, and referral to interventions for women suffering IPV. Many of the interventions included in this review were conducted in health care settings including: primary care (Citation82), specialized medical settings such as drug treatment centres (Citation75), prenatal care sites (Citation64,Citation70), and community centres (Citation61).

In clinical practice, these are easily combined in a women- centred approach (Citation82), where the clinician provides over a series of consultations a mixture of information-giving, safety promotion and planning, motivational interviewing and non-directive problem-solving, and facilitating access to resources and support.

Our study has some limitations. The heterogeneity of the interventions studied and their duration, the differences in the sample sizes, length of follow-up, and the use of various scales to assess IPV limited the pooling of data. We tried to discriminate by conducting comparisons with similar follow-up time-frames and similar numbers of sessions in terms of intensity, but these appeared not to impact significantly on the results. However, the fact that there were only a few studies included may have contributed to this finding. Intensive advocacy interventions (five or more sessions) may be more effective than those with up to five sessions in reducing physical and psychological IPV. Brief CBT interventions (up to five sessions) may be not effective in reducing any IPV, but CBT interventions with over five sessions significantly reduced physical and psychological IPV, suggesting that CBT interventions of longer duration are more effective. However, the low number of CBT trials with interventions of more than five sessions included in the meta-analysis did not allow this to be tested.

These limitations resulted in a limited number of six studies included in the meta-analyses, and the inability to determine the efficacy of some interventions for some types of violence. This in turn may account for the lack of positive results for all trials included. In addition, only one outcome was considered, the frequency or occurrence of IPV, whereas the primary outcome for many trials was quality of life or mental health as it was hypothesized that brief CBT interventions may take longer to affect IPV (Citation82). Therefore, we found a reasonable degree of clinical dissimilarity across trials. Study populations were also heterogeneous: from recruiting from shelters once the victim had already left the abusive relationship (Citation65,Citation67,Citation68,Citation80) to recruiting IPV victims identified using screening tools (Citation61,Citation64,Citation69–71,Citation82). Furthermore, it should be taken into account that, with the exception of Mongolia, the remaining 18 RCTs included in our systematic review were conducted in developed countries such as USA, Australia, and Hong Kong; and one study included African-American women. The results from this meta-analysis could assist professionals in referring IPV victims to the most appropriate intervention modality.

There are several recommendations for future research. Firstly, due to the low number of RCTs, future reviews may consider including other study designs, such as quasi-experimental studies which employed controlled trials without randomization, to increase the statistical power. For sexual IPV, we were unable to conclude whether advocacy and CBT interventions were effective due to insufficient evidence as there were too few studies included in the meta-analysis. Further RCTs are needed to examine effectiveness of CBT interventions in reducing IPV, and whether both (advocacy and CBT) interventions are effective in reducing sexual IPV. A three-arm RCT comparing advocacy and CBT interventions with usual care to reduce IPV should be considered to compare directly the efficacy of these two interventions. No trial reported any adverse effects as a result of participating in their trials. No trial has considered the cost-effectiveness of addressing IPV among victims. This should be included in future trials.

This systematic review and meta-analysis found some support for the effectiveness of advocacy and CBT interventions in reducing physical and psychological IPV. However, the heterogeneous trials and the small effect sizes reported suggest these results should be interpreted with caution. Future intervention trials should include a combination of both types of intervention (advocacy and CBT) to improve outcome for IPV victims over the longer term. For clinicians, it is reassuring to know that the use of CBT interventions have small but encouraging positive effects on IPV, especially for psychological IPV due to the psychological nature of CBT interventions, and should be combined with advocacy and empowerment of women to keep women safe from IPV.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants: RD12/0028/009 from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, Instituto Carlos III-FEDER and INT 12/318. All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and were involved in the interpretation of data.

Declaration of interest: All the authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- World Health Organization. WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

- Vos T, Astbury J, Piers LS, Magnus A, Heenan M, Stanley L, et al. Measuring the impact of intimate partner violence on the health of women in Victoria, Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84: 739–44.

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a metanalysis. J Fam Violence. 1999;14:99–132.

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–6.

- Sarkar NN. The impact of intimate partner violence on women's reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008; 28:266–71.

- Feder G, Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. An evidence-based response to intimate partner violence: WHO guidelines. JAMA. 2013;310:479–80.

- Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Interventions for violence against women: scientific review. JAMA. 2003;289:589–600.

- Stuart GL, O’Farrell TJ, Temple JR. Review of the association between treatment for substance misuse and reductions in intimate partner violence. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:1298–317.

- Trevillion K, Oram S, Feder G, Howard LM. Experiences of domestic violence and mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51740.

- Okuda M, Olfson M, Hasin D, Grant BF, Lin KH, Blanco C. Mental health of victims of intimate partner violence: results from a national epidemiologic survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:959–62.

- Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, Bonomi AE, Reid RJ, Carrell D, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:89–96.

- Liebschutz JM, Rothman EF. Intimate-partner violence—what physicians can do. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2071–3.

- Stover CS, Meadows AL, Kaufman J. Interventions for intimate partner violence: review and implications for evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40: 223–33.

- Ramsay J, Carter Y, Davidson L, Dunne D, Eldridge S, Feder G, et al. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3): CD005043.

- O’Reilly R, Beale B, Gillies D. Screening and intervention for domestic violence during pregnancy care: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11:190–201.

- Jahanfar S, Janssen PA, Howard LM, Dowswell T. Interventions for preventing or reducing domestic violence against pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD009414.

- World Health Organization. Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;23:1023–53.

- Feder L, Wilson D. A meta-analytic review of court-mandated batterer intervention programs: can courts affect abusers’ behavior? Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2005;1:239–62.

- Smedslund G, Dalsbø TK, Steiro A, Winsvold A, Clench-Aas J. Cognitive behavioural therapy for men who physically abuse their female partner. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(3):CD006048.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12.

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley, 2008. p. 187–241.

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008.

- Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19:3127–31.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes. The odds ratio. BMJ. 2000;320:1468.

- Saunders DG. Posttraumatic stress symptom profiles of battered women: a comparison of survivors in two settings. Violence Vict. 1994;9:31–44.

- Zust BL. Effect of cognitive therapy on depression in rural, battered women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2000;14:51–63.

- Kim S, Kim J. The effects of group intervention for battered women in Korea. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2001;15:257–64.

- McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J, Watson K, Batten E, Hall I, et al. An intervention to increase safety behaviors of abused women: results of a randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2002;51:347–54.

- Kubany ES, Hill EE, Owens JA. Cognitive trauma therapy for battered women with PTSD: preliminary findings. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16: 81–91.

- Kubany ES, Hill EE, Owens JA, Iannce-Spencer C, McCaig MA, Tremayne KJ, et al. Cognitive trauma therapy for battered women with PTSD (CTT-BW). J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:3–18.

- Constantino R, Kim Y, Crane PA. Effects of a social support intervention on health outcomes in residents of a domestic violence shelter: a pilot study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005;26:575–90.

- Cruz–Almanza MA, Gaona–Márquez L, Sánchez–Sosa, JJ. Empowering women abused by their problem drinker spouses: effects of a cognitive–behavioral intervention. Salud Mental. 2006;29:25–31.

- Curry MA, Durham L, Bullock L, Bloom T, Davis J. Nurse case management for pregnant women experiencing or at risk for abuse. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:181–92.

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C. A cognitive-behavioral treatment for battered women with PTSD in shelters: findings from a pilot study. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:559–64.

- Resick PA, Galovski TE, O’Brien Uhlmansiek M, Scher CD, Clum GA, Young-Xu Y. A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008; 76:243–58.

- Calderon SH, Gilbert P, Jackson R, Kohn MA, Gerbert B. Cueing prenatal providers effects on discussions of intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:134–7.

- Gillum TL, Sun CJ, Woods AB. Can a health clinic-based intervention increase safety in abused women? Results from a pilot study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18:1259–64.

- Iverson KS, Shenk C, Fruzzetti AE.Dialectical behavior therapy for women victims of domestic abuse: A pilot study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:242–8.

- Crespo M, Arinero M. Assessment of the efficacy of a psychological treatment for women victims of violence by their intimate male partner. Span J Psychol. 2010;13:849–63.

- Cripe SM, Sanchez SE, Sanchez E, Ayala Quintanilla B, Hernandez Alarcon C, Gelaye B, et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: a pilot intervention program in Lima, Peru. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25:2054–76.

- Tiwari AF, Salili F, Chan RY, Chan EK, Tang D. Effectiveness of an empowerment intervention in abused Chinese women. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:25–8.

- Humphreys J, Tsoh JY, Kohn MA, Gerbert B. Increasing discussions of intimate partner violence in prenatal care using Video Doctor plus Provider Cueing: a randomized, controlled trial. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21:136–44.

- Iverson KM, Resick PA, Suvak MK, Walling S, Taft CT. Intimate partner violence exposure predicts PTSD treatment engagement and outcome in cognitive processing therapy. Behav Ther. 2011;42:236–48.

- DePrince AP, Belknap J, Labus JS, Buckingham SE, Gover AR. The impact of victim-focused outreach on criminal legal system outcomes following police-reported intimate partner abuse. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:861–81.

- Tiwari A, Fong DY, Wong JY, Yuen KH, Yuk H, Pang P, et al. Safety-promoting behaviors of community-dwelling abused Chinese women after an advocacy intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:645–55.

- Mitrani VB, McCabe BE, Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Florom-Smith A, Peragallo N. Participation in SEPA, a sexual and relational health intervention for Hispanic women. West J Nurs Res. 2013;35:849–66.

- Wong JY, Tiwari A, Fong DY, Yuen KH, Humphreys J, Bullock L. Intimate partner violence, depressive symptoms, and immigration status: does existing advocacy intervention work on abused immigrant women in the Chinese community? J Interpers Violence. 2013;28: 2181–202.

- McFarlane J, Soeken K, Reel S, Parker B, Silva C. Resource use by abused women following an intervention program: associated severity of abuse and reports of abuse ending. Public Health Nurs. 1997;14:244–50.

- Parker B, McFarlane J, Soeken K, Silva C, Reel S. Testing an intervention to prevent further abuse to pregnant women. Res Nurs Health. 1999; 22:59–66.

- McNutt LA, Carlson BE, Rose IM, Robinson DA. Partner violence intervention in the busy primary care environment. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:84–91.

- Morrissey JP, Jackson EW, Ellis AR, Amaro H, Brown VB, Najavits LM. Twelve-month outcomes of trauma-informed interventions for women with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1213–22.

- Ford-Gilboe M, Wuest J, Varcoe C, Merritt-Gray M. Developing an evidence-based health advocacy intervention for women who have left an abusive partner. Can J Nurs Res. 2006;38:147–67.

- Laughon K, Sutherland MA, Parker BJ. A brief intervention for prevention of sexually transmitted infection among battered women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40:702–8.

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Whitaker DJ, Le B, Crawford TN, Flerx VC. Effect of an in-clinic IPV advocate intervention to increase help seeking, reduce violence, and improve well-being. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:118–31.

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Spiller L, Norwood WD, Swank PR, Stephens N, et al. Reducing conduct problems among children of battered women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:774–85.

- Sullivan CM, Bybee DI, Allen NE NE. Findings from a community-based program for battered women and their children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:915–36.

- Bair-Merritt MH, Jennings JM, Chen R, Burrell L, McFarlane E, Fuddy L, et al. Reducing maternal intimate partner violence after the birth of a child: a randomized controlled trial of the Hawaii Healthy Start Home Visitation Program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:16–23.

- Tiwari A, Yuk H, Pang P, Fong DY, Yuen F, Humphreys J, et al. Telephone intervention to improve the mental health of community-dwelling women abused by their intimate partners: a randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18:14–17.

- Tiwari A, Fong DY, Yuen KH, Yuk H, Pang P, Humphreys J, et al. Effect of an advocacy intervention on mental health in Chinese women survivors of intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:536–43.

- El-Mohandes AA, Kiely M, Joseph JG, Subramanian S, Johnson AA, Blake SM, et al. An intervention to improve postpartum outcomes in African-American mothers: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:611–20.

- Joseph JG, El-Mohandes AA, Kiely M, El-Khorazaty MN, Gantz MG, Johnson AA, et al. Reducing psychosocial and behavioral pregnancy risk factors: results of a randomized clinical trial among high-risk pregnant african american women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99: 1053–61.

- Kiely M, El-Mohandes AA, El-Khorazaty MN, Blake SM, Gantz MG. An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:273–83.

- Sullivan CM, Tan C, Basta J, Rumptz M, Davidson WS 2nd. An advocacy intervention program for women with abusive partners: initial evaluation. Am J Community Psychol. 1992;20:309–32.

- Sullivan CM, Campbell R, Angelique H, Eby KK, Davidson WS 2nd. An advocacy intervention program for women with abusive partners: six-month follow-up. Am J Community Psychol. 1994;22:101–22.

- Sullivan CM, Davidson WS 2nd. The provision of advocacy services to women leaving abusive partners: an examination of short-term effects. Am J Community Psychol. 1991;19:953–60.

- Sullivan CM, Bybee DI. Reducing violence using community-based advocacy for women with abusive partners. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:43–53.

- McFarlane J, Soeken K, Wiist W. An evaluation of interventions to decrease intimate partner violence to pregnant women. Public Health Nurs. 2000;17:443–51.

- Tiwari A, Leung WC, Leung TW, Humphreys J, Parker B, Ho PC. A randomised controlled trial of empowerment training for Chinese abused pregnant women in Hong Kong. BJOG. 2005;112:1249–56.

- McFarlane JM, Groff JY, O’Brien JA, Watson K. Secondary prevention of intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2006;55:52–61.

- Taft AJ, Small R, Hegarty KL, Watson LF, Gold L, Lumley JA. Mothers’ AdvocateS In the Community (MOSAIC)–non-professional mentor support to reduce intimate partner violence and depression in mothers: a cluster randomised trial in primary care. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:178.

- Melendez RM, Hoffman S, Exner T, Leu CS, Ehrhardt AA. Intimate partner violence and safer sex negotiation: effects of a gender-specific intervention. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:499–511.

- Rychtarik RG, McGillicuddy NB. Coping skills training and 12-step facilitation for women whose partner has alcoholism: effects on depression, the partner's drinking, and partner physical violence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:249–61.

- Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Manuel J, Wu E, Go H, Golder S, et al. An integrated relapse prevention and relationship safety intervention for women on methadone: testing short-term effects on intimate partner violence and substance use. Violence Vict. 2006;21:657–72.

- Weir BW, O’Brien K, Bard RS, Casciato CJ, Maher JE, Dent CW, et al. Reducing HIV and partner violence risk among women with criminal justice system involvement: a randomized controlled trial of two motivational interviewing-based interventions. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:509–22.

- Kaslow NJ, Leiner AS, Reviere S, Jackson E, Bethea K, Bhaju J, et al. Suicidal, abused African American women's response to a culturally informed intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:449–58.

- Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Levenson RR, Waldman J, et al. A family planning clinic partner violence intervention to reduce risk associated with reproductive coercion. Contraception. 2011;83:274–80.

- Zlotnick C, Capezza NM, Parker D. An interpersonally based intervention for low-income pregnant women with intimate partner violence: a pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:55–65.

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Perez S. Cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD in residents of battered women's shelters: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:542–51.

- Carlson CE, Chen J, Chang M, Batsukh A, Toivgoo A, Riedel M, et al. Reducing intimate and paying partner violence against women who exchange sex in Mongolia: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27:1911–31.

- Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, Chondros P, Brown S, Valpied J, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:249–58.

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflicted violence: the Conflicts Tactics (CT) Scales. J Marriage Fam. 1981;41:75–88.

- Hudson WW, McIntosh SR. The assessment of spouse abuse: two quantifi able dimensions. J Marriage Fam. 1981;43:873–85.

- Marshall LL. Development of the severity of violence against women scales. Journal of Family Violence. 1992;7:103–21.

- Hegarty K, Sheehan M, Schonfeld C. A multidimensional defi nition of partner abuse: development and preliminary validation of the composite abuse scale. J Fam Violence. 1999;14:399–415.

- Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: the end of routine screening. Lancet. 2013;382:190–1.

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, King MR, McKeown RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:451–7.

- Chang JC, Dado D, Ashton S, Hawker L, Cluss PA, Buranosky R, et al. Understanding behavior change for women experiencing intimate partner violence: mapping the ups and downs using the stages of change. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:330–9.

- Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman L, Dutton MA. Role of distinct PTSD symptoms in intimate partner reabuse: a prospective study. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:507–16.

- Hegarty K. What is intimate partner abuse and how common is it? In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G, editors. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals: new approaches to domestic violence. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2006. p. 19–40.