Abstract

Transplantation provides the best outcomes and quality of life for people with end-stage renal disease and therefore offers the optimum treatment of choice. Preemptive living donor (LD) transplantation is an increasingly preferable alternative to dialysis as transplantation outcomes indicate lower morbidity and mortality rates and greater graft and patient survival rates compared to those who are transplanted after dialysis has commenced. Despite nursing and medical teams giving information to patients regarding transplantation and living donation, the number of people coming forward for preemptive transplant work-up remained limited. Changing the format, environment, and quality of information given to patients and families seemed necessary in order to increase the number of preemptive transplants. Our data show that we have improved the access to the information seminars with attendance rising from 5 to 15 attendees per seminar (3 per year) in 2005 to average 65 attendees per seminar (6 per year) in 2010. By expanding the access to information for patients, their families and friends, living donation has increased with a growth in the proportion of preemptive LD transplants from 28% (23/81) in 2006 to 44% in 2010 (29/66; p = 0.05). We can conclude that expanding the pool accessing information has increased the number of preemptive (LD) transplants in our center.

INTRODUCTION

Transplantation provides the best outcomes and quality of life for people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and therefore offers the optimum treatment of choice. Preemptive living donor (LD) transplantation is an increasingly preferable alternative to dialysis as transplantation outcomes indicate lower morbidity and mortality rates and greater graft and patient survival rates compared to those who are transplanted after dialysis has commenced.Citation1–3 However, in the predialysis setting, it is not unusual for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to be overwhelmed and find it difficult to come to terms with their diagnosis of kidney disease and consequently unable to psychologically cope with considering or digesting information about dialysis and transplantation (deceased or living donation).Citation4

During 2005/2006, we noted that despite nursing and medical teams giving information to patients regarding transplantation and living donation, the number of people coming forward for preemptive transplant work-up remained limited. We considered a number of potential barriers.

The old-style seminars lacked a robust structure as held ad hoc, mid-week, often with limited notice, in small meeting rooms attracting small audiences. They were predominantly nurse-led and essentially process orientated focusing on giving detailed information about the work-up, surgery, and follow-up with limited opportunity for discussing decision-making, influences, and long-term outcomes. Patients typically initially gain information in clinical environments, such as a predialysis clinic or dialysis setting. Arguably neither method of information giving was as conducive for absorbing and assimilating the necessary facts and evidence as they could be.

Living donation is further hampered by a reticence of patients to later discuss the information with family members and a reluctance to ask someone to donate.Citation1,5 Misconceptions over who can be a donor have been observed with a common belief that only blood relatives can, whereas spouses and friends are frequently suitable. Reluctance to accept living donation is common with recipients being fearful for their donor’s post-operative pain, recovery, and potential organ failure.Citation5 Where patients do discuss living donation at home, family and friends keen to learn more were often prohibited from attending mid-week clinic sessions and the existing information seminars.

It was thought that lack of access to information and misconceptions regarding living donation were the principal barriers that prevented potential recipients and donors from coming forward for transplantation that other centers would likely concur.Citation6 Changing the structure, format, and environment was necessary to improve the quality and the way in which information was given to patients and families in order to increase the number of preemptive LD transplants. We needed to ensure patients [potential recipients] and family and friends [potential donors] had ample opportunity to make an informed decision regarding being worked-up as a transplant recipient and also opting for transplantation from a LD where there is often a myriad of psychological processes to overcome.Citation5,7,8

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of changing and expanding access to information on rate and type of donation.

METHODS

In 2006, the seminar format and location was revised using feedback from attendees and analysis of logistical barriers, to both attract and inform a wider audience of potential recipients and donors. A number of key changes were made and evaluated from 2007.

Seminars on Saturdays were introduced and have proved immensely popular for the working audience and have resulted in large groups of family members and friends attending. The seminars needed to be planned as a rolling program and now run every 2 months with dates confirmed for a full year to allow people to plan the timing of their attendance in advance.

A multi-professional team approach was adopted involving surgeons, physicians, and a range of nursing staff including consultant nurse, transplant coordinators, transplant clinic nurses, counselor, predialysis nurse specialists, and dialysis staff. The seminars are facilitated by administrators who support the interface with attendees.

Volunteers who were enlisted have either received or donated a kidney giving them the expertise to provide an account of the process and provide an essential addition to the program. On average 10–12 volunteers willingly attend each seminar, which provides sufficient access for attendees to have the opportunity to discuss their questions. They formally introduce themselves to the audience as the donor or recipient, their relationship to each other, the length of time since their operation, and the type of transplant, all of which provides a powerful message and visually demonstrates the benefits of transplantation. Their transplant experiences are varied with representation from different donor groups and ethnic minority backgrounds. Donors include those who are blood relatives, non-blood relatives, for example, spouses and friends and those who have had blood group incompatible transplants. A young female donor also volunteers who has since successfully started a family which is a crucial issue for many young women who would be potential donors. They are available for informal one-to-one conversations and within a structured facilitated group discussion setting. The breakout group sessions provide a less formal opportunity to ask those pertinent questions and benefit from both the medical expert and the patient. The participation of volunteer patients is crucial to providing an opportunity to recount the reality of their transplant journey experience, add reassurance in terms of visual outcome, and act as a balance to the information given by the multi-professional team.

The new format was changed to include a mix of formal talks and facilitated discussion. By involving a larger multi-disciplinary team, the attendees have the opportunity to meet many people who are involved and responsible for the different aspects of care and appreciate that there are many people available to support them through the process. The transplant coordinators and transplant clinic nurses are available to outline the transplant work-up and post-transplant follow-up; the surgeon provides a detailed account of the operation for both the donor and recipient; and the nephrologist outlines the novel therapies available for those pairs who are blood group incompatible or a positive cross match and explains the possibilities of the paired and pooled program also giving the evidence for long-term outcome to provide reassurance for those considering living donation.

Invitations to the seminars are now sent out systematically to all patients on the national donor waiting list and all predialysis and dialysis patients not on the national waiting list yet deemed suitable for transplantation. Invitation posters are displayed in all clinic and satellite dialysis centers. Contact details for future seminar dates are included. This allows anyone who is not ready to attend (e.g., predialysis patients) or those who cannot make the date, the opportunity to factor in an alternative time to attend. The wider multi-professional team has been extensively informed and now actively encourages their patients to attend with their families and friends.

The venue was changed to accommodate a larger audience with improved facilities and audio visual aids, which have proved immensely valuable especially for those who have visual or audio impairments. Additional rooms are available to facilitate the discussion groups.

Table 1. Type of living donor.

An information pack is given out and each attendee is encouraged to give their feedback and suggestions for improvement. Attendees are encouraged to self-refer as potential donors and recipients following the seminar and are otherwise contacted by the transplant coordinators as a formal follow-up to assess whether further information is required.

Results are expressed as count and proportions. The chi-square test (Fisher’s exact) was used to compare the LD transplant groups and compare the preemptive donor and recipient relationships.

RESULTS

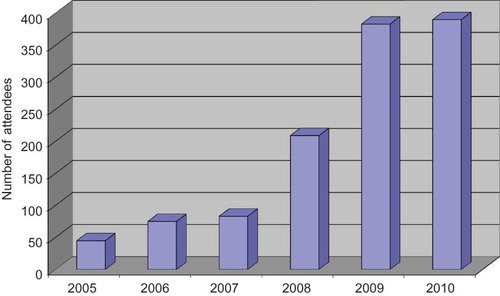

Our data show that we have increased the access to the information seminars with attendance rising steadily following improvements made during 2006 to almost 400 attendees for the past 2 years ().

shows a significant growth in the proportion of preemptive LD transplants from 28% (23/81) in 2006 to 44% in 2010 (29/66) (chi squared p = 0.05).

In 2005, the proportion non-blood-related donors within the total number of LD transplants were small at 28% (11/39) and in 2010 this has risen to 41% (27/66).

The change in the delivery of information seminars is associated with a significant increase in non-blood-related preemptive LD transplants from 25% (3/12) in 2005 to 58% (17/29) in 2010 (chi squared p < 0.05) ().

There has been an increase in donation among the ethnic minority groups with only 39% representation during 2005–2007 versus 52% during 2008–2009.

Considering the relationship between the donor and the recipient, we noticed that wives were the most common relationship. Interestingly, husbands and friends are equally matched in frequency of donation in both the total number of transplants and the preemptive LD transplant group. They are similar in the frequency of each type of blood-related donor, although the relationship (e.g., parent, child, and sibling) varies from year to year with less consistency than the non-blood-related donors.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that a predialysis education program is a significant element of care for patients with ESRD.Citation9 The aim of such a program is to decrease the mystique surrounding treatment, provide patients with objective information about ESRD treatment options, help them make suitable choices, and promote self-care. One study looking at renal replacement therapy choice with a predialysis education program however resulted in only 8 out of 235 having a preemptive transplantCitation9 indicating that additional factors are required to increase preemptive transplantation. Where it is a common belief among renal professionals that self-care therapies are under-used, preemptive transplantation is similarly underutilized. Increasing staff awareness of its benefits was important to achieve our aim.

A prior concern was that performing coronary angiography to assess the suitability for transplantation in CKD patients should be restricted as this test is thought to have an increased risk of complications including a rapid decline to ESRD. However, a study in 2007 provided reassurance as it demonstrated that coronary angiography testing performed using a strict renal protocol did not affect the rate of kidney function decline.Citation10 An additional positive influence has been the emerging local data on the benefits of early transplantation which demonstrate a 98.6% patient survival at 5 years with a preemptive transplant against a 95.5% patient survival when transplanted after dialysis has commenced. Increasing evidence-based knowledge and awareness among our multi-professional colleagues has improved the information given to patients and families and encouraged the referrals of CKD patients to seminars and for work-up.

Non-blood-related, also described as emotionally related living kidney donors,Citation11 have been seen as a valuable option for transplant recipients for some time especially where this avoids the need for dialysis. We have seen a high level of motivation of spouse donation in our center, with wives donating most frequently. It may be argued that the wife component is elevated due to the higher male:female incidence with ESRDCitation12 and be a consequence of sensitization of child-bearing female recipients against their husbands which reduces the likelihood of husbands as potential donors. We deduce that the spousal element of donation relates to the benefit of not only the recipient’s quality of life but the quality-of-life effect this has on the marital and family life with a rise in self-esteem for the donor who has contributed to this improvement as previously reported by Binet et al.Citation11

It is well documented that education is necessary to enable patients to make informed treatment decisionsCitation13 and providing appropriate decision aids is crucial for this to be fully effective. Using decision aids in the form of pamphlets, videos, and discussion in a clinical session has the advantage of outlining the main risks and benefits of transplantation.Citation14 Nevertheless, people learn and make decisions differently and for some it can be too overwhelming to assimilate the information and form a systematic decision about their treatment; instead they rely on a heuristic decision process.Citation15 Decision-making is complex and aids must encompass idiosyncratic values.Citation16 The revision of the seminar format and attention to patient feedback has allowed us to present medical data consistently, clearly explaining the benefits and risks, backed up by pamphlets, and combining this with what patients tell us they want to know.

We know that adults learn continuously from the complex interplay of experiences in their day-to-day lives. Once a patient is equipped with basic information, the foundation is established that allows informal and incidental learning to further occur outside of the formal learning environment.Citation17 The incidental learning is achieved here by focusing discussions in an informal group setting, drawing on the transplant volunteers to help attendees address their personal values and concerns such as how this will impact on their lifestyle.Citation18,19 Having a range of volunteers from different ethnic groups with different experiences allows people to discuss their concerns with someone with similar cultural beliefs and values. Where people are unable to make systematic decisions, the learnt experience of others (transplant volunteers) adds to their otherwise heuristic decision-making.Citation20 Reassurance to alleviate common recipient fears of their donor having pain or long-term health risks is given by presenting scientific outcome data coupled with seeing and hearing how well the donors are from early recovery phase to those who donated many years ago.

The greater multi-professional staff involvement and their commitment together with patients’ feedback at subsequent clinic sessions have perpetuated a word-of-mouth system of encouraging other patients and families to attend. People of other renal centers have been invited to attend by friends and family as a highly informative opportunity. A mixed formal and informal approach to education with the multi-professional team and patient volunteers helps to de-mystify misconceptions such as not having to have dialysis before having a transplant; that risks of transplantation are less than complications of dialysis; and that blood relatives and non-blood relatives can donate.Citation1 By making attendance more accessible for patients’ families and friends to attend, information as to who can donate along with the advantages of living donation often acts as a catalyst for potential donors to offer thus overcoming recipients’ reluctance to ask. It opens up communication with families sharing and supporting patients’ decisions.Citation20

Having the opportunity to speak personally to the recipients and donors is always highly evaluated and for many a crucial decision aid. The overall feedback has been hugely positive with many describing themselves as having better knowledge and reassurance as reported by one individual as “very interesting, [I am] feeling much better about the donor/transplant. Thank you for making it easier to understand and therefore [allowing me] to make the right decision”. Patients and their families attending clinics following seminar attendance to discuss possible LD transplantation are noticeably more knowledgeable and the consultation therefore takes place at an advanced level.

CONCLUSION

We can conclude that changing the structure, format, and timing of the transplant seminar, and formalizing the invitation process has led to an increase in the proportion of preemptive transplants and the proportion of non-related donors in our center. The changes along with increased staff awareness have improved access to information for families and friends. The success of the change has involved attention to feedbacks and a continuous improvement process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has been carried out with the support of B. Rice, O. Ferres, H. Dulku, H. Nunez, K. Tansey, J. Pearson, the transplant recipient and donor volunteers, S. Singh, P. Choi, T. Cairns, R. Charif, D. Taube, and N. Hakim.

Declaration of Interest/Funding: A. Figueiredo received a scholarship from CAPES.

References

- Coorey GM, Paykin C, Singleton-Driscoll LC, Gaston RS. Barriers to preemptive kidney transplantation. Am J Nurs. 2009;109(11):28–37.

- Wolfe R, Valarie B, Ashby MA, Comparison of mortality on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipient of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–1730.

- Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1996;50:235–242.

- Hays R, Waterman AD. Improving preemptive transplant education to increase living donation rates: Reaching patients earlier in their disease adjustment process. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(4):251–256.

- Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC. Living donation decision making: Recipients’ concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(1):17–23.

- Gordon EJ, Caicedo JC, Ladner DP, Reddy E, Abercassis M. Transplant center provision of education and culturally and linguistically competent care: A national study. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2701–2707.

- Symvoulakis E, Komninos ID, Antonakis N, Attitudes to kidney donation among primary care patients in rural Crete, Greece. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:54.

- Burroughs TE, Waterman A, Hong BA. One organ donation, three perspectives; experiences of donors, recipients, and third parties with living donation. Prog Transplant. 2003;13(2):42–50.

- Goovaerts T, Jadoul M, Goffin E. Influence of a pre-dialysis education programme (PDEP) on the mode of renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1842–1847.

- Kumar N, Dahri L, Brown W, Effect of elective coronary angiography on glomerular filtration rate in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009; doi: 0.2215/CJN.01480209.

- Binet I, Bock A, Vogelbach P, Outcome in emotionally related living kidney donor transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;2:1940–1948.

- Tomson C. Chapter 1: Summary of findings in the 2009 UK renal registry report. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;115(Suppl. 1):c1–c2.

- Gordon EJ, Calcedo JC, Ladner DP, Reddy E, Abecassis MM. Transplant center provision of education and culturally and linguistically competent care: A national study. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2701–2707.

- O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD00001431.

- Gigerenzer G, Gaissmaier W. Heuristic decision making. Annual Rev Psychol. 2011;62:451–482.

- Cantillon P. Is evidence based patient choice feasible? BMJ. 2004;329(7456):39.

- Keeping L, English LM. Informal and incidental learning with patients who use continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2001;28(3):313–322.

- Morton RL, Devitt J, Howard K, Anderson K, Snelling P. Patient views about treatment of stage 5 CKD: A qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):431–440.

- Cranney A. Commentary: Decision aids in clinical practice. BMJ. 2004;329(7456): 39–40.

- Morton R, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ. 2010;340:c112, doi:10.1136/bmj.c112.