Abstract

Adolescents with chronic kidney disease (CKD) tend to be isolated from peers who also have CKD, develop non-adherent behavior with treatment recommendations, and consequently are at higher risk for poor health outcomes such as transplant rejection. At the same time, patients in this age group tend to be technologically savvy and well-versed in using Internet-based communication tools to connect with other people. In this study, we conducted semi-structured interviews among adolescents with CKD to assess their information needs and their interest in using a CKD-oriented peer-mentoring website that we are developing, kTalk.org. We interviewed 17 adolescents with CKD, ages 14–18 years old, to learn about (1) any concerns regarding transition from pediatric to adult care teams; and (2) their interest in using the Internet as a source for disease-related information and as a social networking tool for finding and interacting with their peers. The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and qualitatively analyzed. Results showed that (1) the adolescent participants are commonly concerned about transitioning to an adult clinic; (2) they are isolated from peers with the same medical condition who are of similar age; (3) they are frequent Facebook users and are highly interested in exploring the possibility of using an online community website, such as kTalk.org, to discover and communicate with peers and peer mentors; and (4) there exist divergent opinions regarding if an online community of adolescent CKD patients should be open to the public.

INTRODUCTION

The complicated treatment regimens for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) present many unique challenges to adolescents (in this article, defined as ages 14–18 years old). Restrictive diets, medication regimens, and, for some, dialysis schedules underscore how different adolescents with these conditions are from their healthy peers at a time when young people are particularly sensitive to peer group influences.Citation1–3 As a result, adolescents with CKD are more likely to be isolated from other peers who have CKD, develop non-adherent behavior with treatment recommendations, and are consequently at higher risk for poor outcomes such as transplant rejection.Citation4–6 It is no surprise then that some studies suggest that pediatric nephrologists believe many to all adolescents with chronic kidney failure are non-adherent in some fashion.Citation7–9

Peer mentors have been reported to effectively improve the educational process of integrating chronic illness and its treatments.Citation10,11 While peers can serve as a powerful source of support for young people, adolescents with CKD may resist talking face to face with peers to avoid adopting an identity that focuses on their illness. Since patients in this age group tend to be more technologically savvy and utilize social networking websites frequently,Citation12 designing a website that provides social networking for peers with CKD could be one non-threatening way that young people might interact and, in the process, develop peer relationships.Citation13 A recent study of young adults on dialysis aged 18–32, for example, revealed that young adults with ESKD demonstrated improved depression scores after using a peer-mentoring website specifically designed for this age group.Citation14 However, little is known about the specific information needs of adolescents with CKD or how they prefer to interact with peers via Internet-mediated communication technologies. In this study, we conducted semi-structured interviews among 17 adolescents with kidney disease to assess their information needs and their interest in using a CKD-oriented peer-mentoring website that we are developing, kTalk.org.

kTalk.org is a peer-driven online community designed to facilitate information sharing, exchange of social and emotional support, and distribution of patient education materials.Citation15 The pilot implementation of kTalk.org provides features such as a “Talk” function supporting threaded discussions, a “Blogs” section for participants to document and share their stories and feelings, and a “Community” section listing the profiles of all community members allowing the participants to network with each another. However, at present, kTalk.org was exclusively designed for young adults entering their earlier adulthood. The purpose of this study was to learn how the unique needs of adolescents with CKD could be addressed using kTalk.org.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Approval to interview adolescents with CKD was obtained through the University of North Carolina (UNC) Institutional Review Board. Adolescents aged 14–18 treated at the UNC Kidney Center pediatric nephrology clinic were eligible to participate. An adolescent youth worker or transition coordinator conducted individual private structured interviews with prevalent patients as part of their routine clinical care. Our group felt that this interviewing structure would better assure subject comfort to answer questions openly.

The interview protocol was jointly developed by an interdisciplinary research team. Two peer mentors with CKD helped pilot-test the protocol to refine its structure and language. The final protocol contains 12 questions and 8 probing questions covering a wide spectrum of topics such as whether the subjects know other adolescents with kidney disease and their current interactions, difficulties in coping with kidney disease, comfort level with their care providers and concerns about transitioning to an adult clinic, general and CKD-specific Internet usage, the adolescents’ interest in participating in online communities designed specifically for patients in this age group, in addition to desired as well as undesired features. The complete interview protocol is presented in Appendix. Note that because of the semi-structured nature of the study, additional questions might be asked based on participants’ responses, and the question included in the protocol might not be necessarily asked in the predetermined order.

At the start of each interview, the participant was shown a brochure describing an earlier implementation of kTalk.org, a CKD-oriented website for young adults. All interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and then coded to facilitate subsequent analyses.

The analyses were performed through three steps: (1) two co-authors (KZ and LT) independently examined a few seed transcripts and derived common thematic categories from the data; the results were then consolidated and iteratively refined throughout the remaining coding process; (2) a third researcher (EEP) conducted face validation of the thematic coding results; and (3) the research team developed a consensus on salient, reoccurring themes and how the results may help inform the design of online communities, such as kTalk.org, to support this special patient population. Because the amount of the data was relatively small, we did not use any qualitative analysis software to aid in the analysis processes.

RESULTS

Sample Demographics

presents the demographics of the study sample. Among the 17 adolescents who participated, black and white were equally represented, and each race group was composed of five males and three females. Many of these adolescent participants were diagnosed with CKD at a young age as the median age of diagnosis was 2 years. All of them were either pre-ESKD (7, 41.2%) or had received a kidney transplant (10, 58.8%) when this study was conducted. On average, they took about seven different types of medications per day for CKD-related treatments.

Table 1. Patient characteristics (N = 17).

Descriptive Analysis

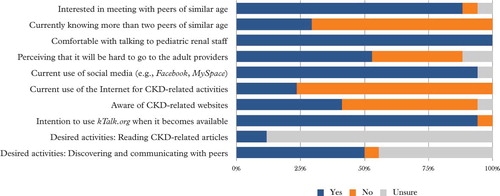

Several interview questions were phrased in a quantitative or dichotomized manner (e.g., “How many other young people, about your age, do you know with chronic kidney disease?” and “Would you be interested in trying [the website] out?”); many participants provided definitive answers to them. We analyzed such responses separately and present the results in a visual form in .

As shown in the figure, while nearly all adolescent participants expressed an interest in meeting with other CKD patients of their age, a majority of them did not know many such peers they could connect with (mean: 1.8, median: 1); 7 out of 17 (41.2%) did not know any other adolescents with CKD. Further, all participants provided a positive response to the question regarding their comfort level of talking to renal staff. However, more than half of the subjects expressed concerns regarding transferring to adult-focused health providers.

All of the adolescent participants are regular users of social media websites, for example, Facebook and MySpace. However, only four of them had used the Internet for CKD-related activities such as searching for disease-related information or connecting with other patient peers. More than half of them were not aware of any websites designed for patients with CKD; none were able to name a website that allows them to get to know and interact with other young patients of their age.

When asked if they might be interested in participating in an online community, such as kTalk.org shown to them at the beginning of the interviews, all but one expressed an interest. The person who was not interested was already connected with seven patient friends. Among the various features discussed that could be potentially provided by such a website, discovering and communicating with peers of their age was rated most useful. As for reading disease-related articles, most participants were not sure how helpful they might be because of other alternatives that they already had.

Thematic Analysis

The thematic analysis identified four major themes that further reinforced the descriptive analysis results reported earlier. We found that (1) the adolescent participants of the study are commonly concerned about transitioning to an adult-focused clinic; (2) they are isolated from peers who also have CKD; (3) they are frequent Facebook users and are highly interested in exploring the possibility of using an online community website, such as kTalk.org, to discover and communicate with peers and peer mentors; and (4) there exist divergent opinions regarding whether an online community of adolescent CKD patients should be open to the public. Below, we present each of these themes in more detail.

First, the adolescents we interviewed had a strong emotional attachment to their current renal team, which could be a major source of the concerns they expressed regarding the transition to an adult-focused clinic. For example, a participant commented that “They’re [adult providers] not going to know you so well . . . They [current renal team] watch you grow up.” Further, the data indicate that the adolescents’ perception about adult kidney care was considerably influenced by the opinions and experiences of their parents and relatives: “. . . Because they won’t treat me like how I get treated here. My mom said that when I get older and move to the adult side they are going to treat you like crap. I’ve seen the way when my uncle was in the hospital . . . They didn’t treat him so good.”

Second, while a majority of the adolescents wished to get to know and interact with other young patients of their age (e.g., “Yes that’d be exciting to meet them”), they felt inadequately supported to develop such interpersonal social networks. Geographic barriers were cited as a major obstacle: “There are none where I live,” in addition to the lack of information about other adolescents with CKD: “[do not already communicate with peers] Because I don’t know any other young people that have kidney disease.” Further, some study participants expressed that they did not have an efficient approach to stay in touch with peers they already knew: “I used to [communicate with them], but then I got a new phone and lost their numbers.”

Third, despite the fact that the adolescent participants of this study spent on average 2 h per day on the Internet, a majority of them were not aware of any websites designed for CKD patients, none targeting specifically their age group. They are, however, regular users of general-purpose social networking tools such as Facebook and MySpace. When asked if they saw the potential of using similar online tools to allow them to connect with other adolescent patients to share information and emotional support, the responses were overwhelmingly positive:

Maybe talk with other children or teens just like them, because I know I’ve been talking to other people with kidney transplants and they have been telling me their experiences. Like my creatinine fluctuated and at first I was like “oh my gosh, this is so bad.” Then somebody my mom knows said yea that happened to me and somebody else I met said yea that happened to me. They are alright now.

To learn about what kind of medicines I take and other people who have the same thing I have and how to deal with it. Find out what harm they are in if they don’t take their medicine. How long it will last and all this kind of stuff. Talk with other kids and see what their opinions [are].

Lastly, among the 17 participants, their opinions diverged regarding if such an online community designed to support adolescents with CKD should be open to the public. Three salient themes were identified from the data; each was supported by about one third of the participants. Some of the participants believed that the community should be accessible only to patients and families. Others expressed that they would not feel threatened if the website might be selectively open to certain non-patient users, for example, “People that help children and work with them . . . I guess it’s fine if they have a purpose in there,” and “Maybe people like high school people. Maybe they would want to research on it like a project on it. They could go on it and find information.” Further, a considerable proportion of the participants were explicitly in favor of opening the site up to others who may be interested, so that the issues and challenges that adolescents with CKD are confronted with will be known to other people: “A lot of family and friends are in the dark they don’t know every aspect of what’s going on. What is this? So they need to be informed about it too.”

DISCUSSION

There has been growing attention to the fact that, while adolescents constitute only 0.01% of the ESKD population,Citation4 there are no figures for the number of prevalent children, adolescent, or emerging adult patients with CKD. Yet there is considerable cost, financial and otherwise, in not addressing the needs of patients in this age group.Citation5 Part of the difficulty in the healthcare transition is that adolescents’ perception of risk differs developmentally from older adults. Young people tend to be more concerned about how their health behavior will interfere with school, recreation, and daily routines rather than the impact to their physiological well-being.Citation6 Unfortunately, many risk-taking behaviors track into young adulthood.Citation9 In addition, characteristic of this age group includes the drive to challenge the traditional power structure of adult to child,Citation13 thus late adolescents with CKD often lend “a deaf ear” to staff lectures on good health self-maintenance.Citation14

Though the majority of young people use the Internet daily,Citation16,17 a website with education as a sub-context could easily fail to effectively reach an adolescent target if it appears in the format of the traditional adult–child power hierarchy.Citation18,19 Rather, the development of a website for adolescents with CKD requires consultation with the target audience to effectively meet their needs. The results obtained from this study provide several such design implications. We show that the primary objective of such websites should be focused on supporting peer discovery, communication, and information sharing.

Further, this group of adolescent patients with CKD seems to feel quite secure in their care in their pediatric renal clinic and in the care of their pediatric renal team. They can joke with the team and feel “special.” They average a great number of medications per day and one comment about this particular stressor of CKD complained: “I’m just a little kid!” Another felt that keeping up with all the medications was very difficult. From the comments about never wanting to grow up and concerns about not receiving the same amount of help from adult-focused providers, it is clear that transition is a concern for most of them. Most do not know any other adolescent with CKD and all but one were interested in interacting with others who might have similar issues through the Internet. One subject mentioned that hearing from someone else that they also had a rise in his creatinine instantly reassured him and that having access to others with transplants could be very helpful.

All adolescents we interviewed spend time on the Internet and most are regular users of Facebook. They were very interested in participating in a customized online community where they can meet other adolescents with CKD and share information and emotional support with them. By doing so, they also want to show that “even though we had a kidney transplant it doesn’t mean we can’t be like normal people.” Comments on the need for privacy ranged from wanting only adolescents with CKD on the website to having it open to everyone depending on the issues discussed. One comment indicated that the patient did not want the website to be invaded by cyber bullies and predators. However, many were not concerned and some even wanted non-patients to join the community so that their stories could be heard widely.

There are, however, several limitations to the current study. The relatively small sample size from a single center may lead to a biased assessment of the concerns and needs of adolescent patients. Certain demographic factors, such as age at diagnosis and socioeconomic status, may likely affect which aspects of a website may be more or less preferred or whether a CKD website is even valued at all. Nonetheless, it is clear that we must develop new ways to help this population feel supported and learn ways to incorporate this complex disease and its treatment into their lives. Nephrology has several underutilized tools to help adolescents reach this goal: peer mentoring, website education, and the combination of the two. Additional study is needed to test the generalizability of these findings to other adolescents with CKD and understand specific informational needs from the perspective of pediatric and internal medicine nephrologists and other members of the healthcare team so that an effective CKD website can be developed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Renal Research Institute for a grant to help us develop a website for adolescents and emerging adults with CKD.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Ferris ME, Gipson DS, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW. Trends in treatment and outcomes of survival of adolescents initiating end-stage renal disease care in the United States of America. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(7):1020–1026.

- Dittmann RW, Hesse G, Wallis H. Psychosocial care of children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease—problems, tasks, services. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 1984;23(3):97–105.

- Bell L. Adolescents with renal disease in an adult world: Meeting the challenge of transition of care. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(4):988–991.

- NIDDKD. United States Renal Data System 2009 Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD: NIH.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. End-Stage Renal Disease: Characteristics of Kidney Transplant Recipients, Frequency of Transplant Failures, and Cost to Medicare; 2007. Report No. GAO–07–1117, Washington, D.C. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d071117.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2011.

- Harwood L, Johnson B. Weighing risks and taking chances: Adolescents’ experiences of the regimen after renal transplantation. ANNA J. 1999;26(1):17–21.

- Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Rayner HC, Nonadherence in hemodialysis: Associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):254–262.

- Watson AR, Shooter M. Transitioning adolescents from paediatric to adult dialysis units. Adv Perit Dial. 1996;26:176–178.

- Kelder SH, Perry CL, Klepp KI, Lytle LL. Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviors. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(7):1121–1126.

- Kapron K, Perry E, Bowman T, Swartz RD. Peer resource consulting: Redesigning a new future. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1997;4(3):267–274.

- Perry E, Swartz J, Brown S, Peer mentoring: A culturally sensitive approach to end-of-life planning for long-term dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(1):111–119.

- Gross EF. Adolescent internet use: What we expect, what teens report. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2004;25(6):633–649.

- Drew SE, Duncan RE, Sawyer SM. Visual storytelling: A beneficial but challenging method for health research with young people. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(12):1677–1688.

- Perry EE, Zheng K, Grogan-Kaylor A, Assessing the effect of a technology-based peer-mentoring intervention on renal teams’ perceived knowledge and comfort level working with young adults on dialysis. J Nephrol Soc Work. 2010;33:8–12.

- Zheng K, Newman MW, Veinot TC, Using online peer-mentoring to empower young adults with end-stage renal disease: A feasibility study. AMIA Annual Symp Proc. 2010;2010:942–946.

- Sarasohn-Kahn J. The Wisdom of Patients: Health Care Meets Online Social Media. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2008.

- Hawn C. Take two aspirin and tweet me in the morning: How Twitter, Facebook, and other social media are reshaping health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):361–368.

- Cosaro WA. The Sociology of Childhood. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press; 2005.

- Matthews SA. A window on the “new” sociology of childhood. Soc Compass. 2007;1:322–334.