Abstract

There are many infectious complications related to vascular access in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. We report two cases of endophthalmitis as a metastatic infection associated with a tunneled catheter and a temporary dual lumen catheter. Both patients were diabetic. A 61-year-old female on maintenance hemodialysis by a jugular tunnelized catheter during the past year was receiving parenteral antibiotics for catheter salvage due to fever episodes in the last 3 months. She was admitted to the hospital presenting pain, proptosis, conjunctival hyperemia, corneal infiltrate, and visual acuity of no light perception (NLP). A 51-year-old male recently undergoing hemodialysis by a temporary dual lumen catheter presented fever. His catheter was removed, but he was admitted to the hospital presenting fever, decreased vision, edema, and pain in his left eye. On examination, eyelid edema, conjunctival hyperemia, purulent secretion, hypopyon in the pupils, and visual acuity of NLP were verified. A diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis was made in both patients on clinical grounds and computed tomography. Evisceration of the left eye was the first option of treatment for both patients due to poor vision. Cultures of the eviscerated ocular globes showed Staphylococcus hemolyticus and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively. After evisceration, both patients received treatment, had a good outcome, and were discharged to continue their hemodialysis program. Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis is a rare complication of dialysis catheter-related bacteremia. When suspected, urgent ophthalmologic evaluation and treatment are needed to reduce the risk of losing vision in the affected eye.

INTRODUCTION

The use of temporary (noncuffed) and semipermanent (cuffed) dual lumen catheters remains an essential component of dialysis practice for the management of acute renal failure, as a temporary access for a patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who will need urgent dialysis therapy or even in patients who lose their native arteriovenous fistula (AVF).Citation1 AVF is the best form of access to the circulation for maintenance hemodialysis. Furthermore, AVF reduces the risk of bacteremia compared with other access devices, such as polytetrafluoroethylene grafts, tunneled dialysis catheter, and the emergency temporary dialysis catheter.Citation2

Staphylococcus sp., especially Staphylococcus aureus, have been found in approximately half of the dialysis population.Citation3 Major complications from vascular access are severe sepsis, metastatic osteoarticular infections, infective endocarditis, and, more rarely, endophthalmitis.Citation3 We report two cases of metastatic infection in the form of acute endophthalmitis in patients with catheter-related sepsis, and we make some observations on their clinical outcome.

CASES

Case 1

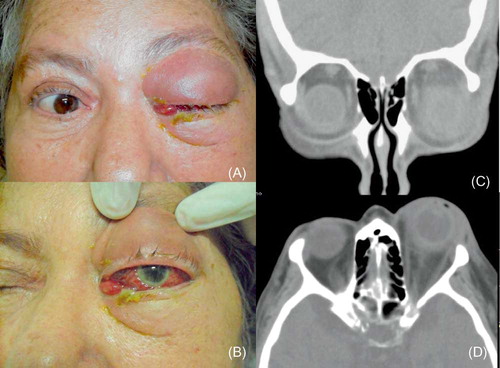

A 61-year-old female, maintained on hemodialysis during the past 3 years due to ESRD and type 2 diabetes, was referred because of an infection in the area of the left eye. She had a thrombosis in her native AVF and was submitted to hemodialysis by a tunnelized catheter in the past year (jugular vein). For the past 3 months, she presented pyrogenic episodes during hemodialysis sessions. The patient received parenteral antibiotics for catheter salvage. Eleven days before her admission to the hospital, she was treated with ceftriaxone due to pneumonia. She was admitted because of pain, proptosis, conjunctival hyperemia, corneal infiltrate (A and B), and visual acuity of no light perception (NLP). Examination of the right eye was unremarkable. Computed tomography (CT) showed proptosis and diffuse orbital infiltrate (C and D). This patient had no previous history of ocular surgery or trauma, so a diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis with orbital cellulitis was made on the basis of the clinical history, findings, and CT. Evisceration of the left eye was the first option of treatment due to poor vision. The catheter was removed, and hemocultures were collected. Endocarditis was discarded. Hemocultures were all negative, but the culture of the eviscerated ocular globe showed vancomycin-sensitive Staphylococcus hemolyticus. The patient was treated with vancomycin and meropenem, had a good outcome, and was discharged after treatment according to her dialysis program.

Case 2

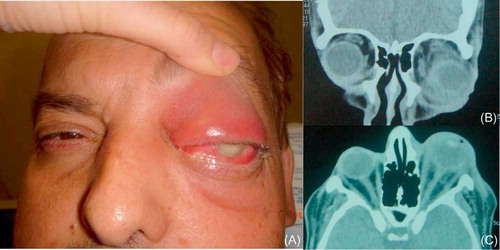

A 51-year-old man who was recently placed on hemodialysis due to ESRD and type 2 diabetes by a temporary dual lumen catheter during the past month was admitted to another hospital with fever. The catheter was withdrawn due to local infection and fever, and after the patient was discharged, the fever persisted. Three days after his discharge, he was admitted to this hospital presenting fever, decreased vision, edema, and pain in his left eye. On examination, eyelid edema and conjunctival hyperemia, purulent secretion, hypopyon in the pupils (A and B), and visual acuity of NPL were verified. This patient had no history of an ocular trauma and surgeries in the past. The other eye did not show alterations. An orbital CT showed diffuse orbital cellulitis (C). A diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis was made, and evisceration was the chosen option due to poor vision. The hemocultures were negative. Endocarditis was discarded, and the cultures of the eviscerated eye were positive for S. aureus. The patient received treatment with cefepime and vancomycin, had a good outcome, and was discharged to continue his hemodialysis program.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reported two cases of left unilateral endogenous endophthalmitis associated with access of the catheter to hemodialysis, which had a poor outcome. In both cases, the patients were diabetic, which usually is an underlying disease in patients with endogenous endophthalmitis.Citation4 Eye evisceration was needed in both cases.

Bacterial endophthalmitis can be classified as exogenous or endogenous and is a medical emergency. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis (also referred to as metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis) is a rare disease that accounts for 2–8% of all cases of endophthalmitis, depending on the clinical study.Citation5 It has been associated with a number of chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure.Citation6 In the literature, as far as we know, there are four reported cases associated with the use of prosthetic devices as access to hemodialysis ().Citation7–10 There are another few reported cases that are associated with AVF infection.Citation5,11 Gram-positive bacteria are the most common pathogens.Citation5

Table 1. Cases of endogenous endophthalmitis described in the literature as a complication of hemodialysis catheter-related bacteremia.

There is a higher incidence of involvement of the right eye, although the left eye was involved in both cases reported here.Citation5 Concurrent cellulitis and endophthalmitis that resulted from endogenous complications have been reported in the literature but are usually caused by Gram-negative microorganisms.Citation12,13

Unfortunately, the first option of treatment was evisceration in both cases because the visual acuity of these patients was NLP and, therefore, they were without visual prognosis. The evisceration can give to these patients a better outcome and fast relief of the ocular symptoms. In these cases, systemic cultures were negative, and the microorganisms were identified by ocular culture that is usually positive in 36–73% of cases.Citation4 Thus, ocular culture was essential to confirm the pathogen and guide the treatment. After evisceration was performed and prolonged antibiotic treatment was provided, the outcome of both patients was good. Most of the time, patients with some vision such as luminous perception should receive parenteral antibiotics in addition to intravitreal antibiotics and sometimes vitrectomy.Citation4,8,14

In case 1, there were many attempts at the tunneled catheter salvage with parenteral and oral antibiotics without success. The risk of salvaging the access catheter in cases of infection increases the probability of metastatic infections such as epidural abscesses, endocarditis, discitis, and myocardial abscesses.Citation15,16 In case 2, the patient was undergoing hemodialysis for the first time with a temporary dual lumen catheter, which had been withdrawn because of signs of local infection and fever. The patient most probably had bacteremia, and sometimes this bacteremia can be silent; however, catheters could already be colonized.Citation17,18

The use of temporary or semipermanent hemodialysis catheters remains an essential component of dialysis, especially in patients who need urgent dialysis therapy or even in patients who lose their native AVF. Unfortunately, the use of these devices often involves mechanical or infectious complications. Using fewer prosthetic devices can reduce catheter-related bacteremia and colonization. AVF should be the preferential access to patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis in all cases, although it could be also a source of infection. In fact, bacteremia caused by mostly Gram-positive bacteria and provoked by many causes, including peritonitis, endocarditis, kidney infection, hemodialysis catheters, and even AVFs, could cause a metastatic infection in the eyes.Citation4–7

Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis is supposed to be a rare complication of dialysis catheter-related bacteremia, but it could be simply less reported than other severe infections such as sepsis, osteoarticular infections, and endocarditis. When suspected, urgent ophthalmologic evaluation and treatment is needed to reduce the risk of the loss of patient vision in the affected eye as reported in both cases in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Fundação de Assistência ao Ensino, Pesquisa e Assistência (FAEPA).

Authors’ contributions. All authors were involved in writing/reviewing the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Mermel LA. Prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:391–402.

- Vas SI. Infections related to prosthetic materials in patients on chronic dialysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8:705–708.

- Vandecasteele SJ, Boelart JR, De Vriese AS. Staphylococcus aureus infections in hemodialysis: What a nephrologist should know. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1388–1400.

- Lemley CA, Han DP. Endophthalmitis, a review of current evaluation and management. Retina. 2007;27:662–680.

- Okada AA, Johnson RP, Liles C, D´Amico DJ, Baker AS. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis; Report of a ten-year retrospective study. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:832–838.

- Faeber BP, Weinbaum DL, Dummer JS. Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:62–64.

- Bloomfield SE, David DS, Cheigh JS, . Endophthalmitis following Staphylococcal sepsis in renal failure patients. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138:706–708.

- Smith KGC, Ihle BU, Heriot WJ, Becker GJ. Metastatic endophthalmitis in dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 1995;15:78–81.

- Saleem MR, Mustafa S, Drew PJT, . Endophthalmitis, a rare metastatic bacterial complication of hemodialysis catheter-related sepsis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:939–941.

- Sychev DS, Maya ID, Allon M. Clinical outcomes of dialysis-catheter related candidemia in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;4:1102–1105.

- Madhav D, Rapoor R, Gudithi SL, Kumar R, Prasad N, Dakshinamurty KV. Endophthalmitis: A rare complication of arteriovenous fistula infection. Hemodial Int. 2008;12:227–229.

- Luemsamran P, Pornpanich K, Vangveeravong S, Mekanandha P. Orbital cellulitis and endophthalmitis in pseudomonas septicemia. Orbit. 2008;27:455–457.

- Argelich R, Ibáñez-Flores N, Bardavio J, Burés-Jelstrup A, García-Segarra G. Orbital cellulitis and endogenous endophthalmitis secondary to Proteus mirabilis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64(4):442–444.

- Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. A randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1479–1496.

- Kovalik EC, Raymond JR, Albers FJ, . A clustering of epidural abscesses in chronic hemodialysis patients: Risks of salvaging access catheters in cases of infection. J Am Soc Nephrology. 1996;7:2264–2267.

- Troidle L, Eisen T, Pacelli L, Filkenstein F. Complications associated with the development of bacteremia with Staphylococcus aureus. Hemodial Int. 2007;11:72–75.

- Dittmer ID, Sharp D, McNully CAM, Williams AJ, Banks RA. A prospective study of central venous hemodialysis catheter colonization and peripheral bacteremia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;51:34–39.

- Freitas LWC, Moyses Neto M, Nascimento MMP, Figueiredo JFC. Bacterial colonization in hemodialysis temporary dual lúmen catheters: A prospective study. Ren Fail. 2008;30:31–35.