Abstract

A 43-year-old man with a cardiac device for dilated cardiomyopathy presented with fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Investigations revealed pancytopenia, acute renal failure, abnormal lung function, and raised inflammatory markers. A renal biopsy demonstrated pauci-immune necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis. He was diagnosed with pulmonary–renal antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-negative systemic small vessel vasculitis. He commenced immunosuppression with prednisolone and cyclophosphamide with recovery from pancytopenia and improvement in renal function 3 months later. Subsequently, a bone marrow culture grew Mycobacterium fortuitum. Isolation on repeat peripheral mycobacterial blood cultures prompted treatment with ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin. Four months later, he presented with neutropenic sepsis, influenza A/H1N1, and Aspergillus flavus pneumonia. Despite treatment he deteriorated. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a vegetation on the right ventricular pacing wire. The device was removed. The vegetation revealed acid and alcohol fast bacilli on Ziehl–Neelsen staining and grew M. fortuitum on culture, sensitive to ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin. Despite device removal and antimicrobial therapy, the patient succumbed to treatment-related complications. The association between glomerulonephritis and endocarditis is well known; however, this is the first case to our knowledge describing pauci-immune necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis in the context of M. fortuitum endocarditis. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for endocarditis in patients with a cardiac device who present with fever and pauci-immune necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis. Patients should be investigated with mycobacterial blood cultures, at least three sets of standard blood cultures and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Clinicians should beware the perils of immunosuppression in the face of an occult sepsis.

INTRODUCTION

With an aging population and a growing list of indications, implantable cardiac devices are used increasingly in medical practice with an estimated 200,000 now inserted worldwide per year.Citation1 Complications relate to device insertion, mechanical malfunction, or infection. One large prospective study reported an incidence of 0.68 infections per 100 patients in the 12 months subsequent to implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) insertion.Citation2 Patients with an infected cardiac device may present with fever; however, the presence of an intravascular foreign body may make them susceptible to atypical syndromes and immune complications including renal failure. On presentation the differential diagnosis in these cases is wide and includes infective, collagen vascular, autoimmune, and malignant diagnoses. These patients must be carefully assessed to avoid making an incorrect diagnosis.

CASE HISTORY

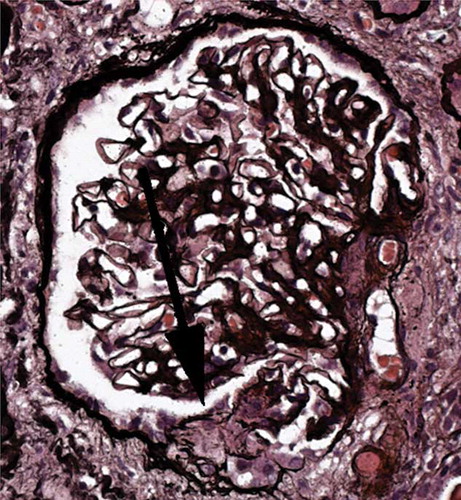

A 43-year-old ex-health services management consultant presented to his local hospital in July 2009 with a 9-month history of fever, night sweats, and weight loss. He had a biventricular pacemaker and ICD inserted in 2005 for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. On examination he was afebrile and his heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate were normal. There were no systemic features of vasculitis or endocarditis and no evidence of a pacemaker pocket infection. Aside from pansystolic murmurs of mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, general examination was normal. Initial investigations showed that he had progressive renal impairment over the previous 3 months with pancytopenia and raised inflammatory markers ( and ). Bedside urinalysis showed 4+ microscopic hematuria, 3+ proteinuria, and a urine protein and creatinine ratio quantified at 270 mg/mmol. A serum angiotensin-converting enzyme level and rheumatoid factor were elevated and tests for autoantibodies comprising antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), antihuman lysosomal membrane proteins (hLAMP), collagen vascular disease, and blood-borne viruses including human immunodeficiency virus were negative (). A chest X-ray showed increased airspace shadowing within the right and left lobes with patchy mid-zone airspace shadowing. Thoracic computed tomography (CT) revealed ground glass shadowing bilaterally with widespread ill-defined parenchymal nodularity without lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary function tests showed a mild obstructive lung defect [forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity of 72%, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) of 71% with a DLCO corrected for alveolar volume carbon monoxide transfer coefficient of 130%]. Three sets of peripheral blood culture samples were taken, of which one was reported as negative at Day 5. Sputum and early morning urine samples were negative on Ziehl–Neelsen staining for mycobacterial acid and alcohol fast bacilli (AAFB). A bone marrow aspirate taken to investigate the pancytopenia showed normal cellularity. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrated regurgitation across the mitral and tricuspid valves with an ejection fraction of 20%, and there was no evidence of valvular vegetations or a pacemaker infection. In view of his renal impairment and active urine sediment he underwent renal biopsy. This demonstrated a pauci-immune focal necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritisCitation3 ().

Figure 1. Changes in creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) over time.

Table 1. Results of hematological and biochemical investigations.

Table 2. Results of additional investigations.

Figure 2. Renal biopsy. Glomerulus showing an acute segmental lesion (arrowed) with a well-demarcated collection of cells in Bowman’s space, overlying a capillary loop with thrombosis and disruption of the basement membrane, characteristic of an acute necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis with an index of chronicity of 20%. The immunoperoxidase study showed no significant deposition of immunoproteins in the glomeruli.

Based on the constitutional symptoms, renal biopsy, and pulmonary pathology, the patient was diagnosed with pulmonary–renal ANCA-negative systemic small vessel vasculitis and commenced immunosuppression 17 days following presentation with prednisolone 60 mg and cyclophosphamide 100 mg orally, once daily (OD). He was discharged from hospital on Day 22. His general condition improved with recovery from pancytopenia and a corresponding fall in serum creatinine to a nadir of 1.70 mg/dL 3 months later (Day 92, and ).

The bone marrow aspirate taken on Day 17 was sent for routine mycobacterial culture. This grew a Mycobacterium species 8 days later, which was later identified as Mycobacterium fortuitum. The patient was recalled to the unit and a repeat peripheral mycobacterial blood culture was taken on Day 27. This confirmed a blood-borne Mycobacterium species on Day 39. He commenced empirical clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily (BD) and ciprofloxacin 500 mg BD on Day 42. The organism was again identified as M. fortuitum and was sensitive to both drugs. A bronchoscopy on Day 32 demonstrated free blood in the bronchial tree and hemosiderin-laden macrophages; however, culture for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial organisms of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was negative.

On Day 127, the patient presented with dyspnea and deteriorating renal function. He was neutropenic with an acute kidney injury and severe sepsis syndrome ( and ). A nasopharyngeal swab confirmed the presence of influenza A/H1N1 by polymerase chain reaction. A thoracic CT showed confluent ground glass shadowing in the right upper lobe with nodular areas of ground glass change throughout the lungs and consolidation in the apical segment of the right lower lobe. Repeat peripheral mycobacterial blood cultures were negative. The immunosuppression was discontinued. Empirical parenteral antimicrobial therapy with teicoplanin 400 mg OD and meropenem 1 g BD with oseltamivir 75 mg BD were added to his antibiotic regimen.

The patient deteriorated with severe hemoptysis and respiratory failure requiring continuous oxygen therapy via a face mask. A repeat thoracic CT 2 weeks later now demonstrated early cavity formation in the right upper lobe with progression of ground glass shadowing. Aspergillus flavus was isolated from his sputum prompting antifungal treatment with voriconazole. This was converted to liposomal amphotericin B because of visual hallucinations. He developed acute liver injury and accordingly clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin were withdrawn. A liver biopsy demonstrated cholestasis and a venostatic picture with no granulomata consistent with advanced right heart failure.

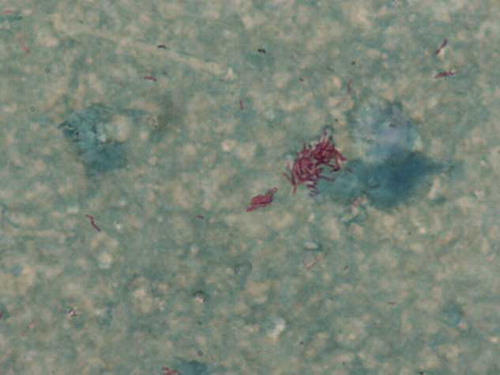

A repeat TTE on Day 157 revealed a vegetation on his right ventricular pacing lead. He recommenced clarithromycin 500 mg BD and ciprofloxacin 500 mg BD with the addition of amikacin 300 mg BD the following day. The ICD was removed on Day 163 and the vegetation recovered from the right ventricular pacing lead demonstrated AAFB on direct staining and grew M. fortuitum on culture, which remained sensitive to clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin ().

Figure 3. Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) staining of right ventricular pacing lead vegetation. This shows numerous acid and alcohol fast bacilli (AAFB) on direct staining and grew Mycobacterium fortuitum upon culture.

As previous ICD interrogations had not indicated any arrhythmias, a further ICD insertion was planned at a later date once the mycobacterial infection had fully resolved. However, 4 days after removal of the device, the patient deteriorated with cardiac and renal failure requiring hemodialysis (). On Day 186 he suffered from a cardiopulmonary arrest from which he could not be resuscitated. A postmortem examination was declined.

DISCUSSION

We discuss here a case of a man with chronic infection due to M. fortuitum, who presented with an ANCA-negative pulmonary–renal vasculitic syndrome. Initially there was no evidence of a pacemaker pocket infection, the TTE did not show evidence of endocarditis, and the patient did not meet Duke’s criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. M. fortuitum is not an organism typically associated with infective endocarditis, although appropriate empirical therapy was commenced. The relationship between the start of the immunosuppression and the isolation of the atypical Mycobacterium was unclear and the atypical Mycobacterium was initially thought to be related to immunosuppression. Immunosuppressive therapy was withdrawn when the patient presented with neutropenic sepsis. Unfortunately, by then the infection had progressed and the patient eventually succumbed.

It is well known that endocarditis can cause glomerulonephritis, the commonest type being vasculitic, without deposition of immune complexes in the glomeruli,Citation4 contrary to the commonly held view of hypocomplementemic immune complex deposition renal injury. This case emphasizes that all cases of pauci-immune necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis should be assessed fully to exclude endocarditis. This should include mycobacterial blood cultures and at least three sets of standard blood cultures prolonged for at least 21 days to exclude fastidious organisms and facilitate the detection of atypical mycobacteria and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography.

Although the patient described was consistently anti-nuclear antibody-negative, anti-glomerular basement membrane-negative, and ANCA-negative, there was a high titer of rheumatoid factor, which was shown in a prospective study to improve the specificity of the diagnosis of culture-negative endocarditis where 8% of cases had a positive result.Citation5 Extrarenal manifestations in ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis are rare.Citation6,7 Testing for hLAMP antibodies, which have recently been shown to be associated with pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis and infections with fimbriated pathogens,Citation8 was also negative. There are similarities to another reported case where polyclonal rheumatoid factor was linked to the presence of hemolytic anemia and pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis in a patient with right-sided mixed staphylococcal and streptococcal endocarditis. The authors postulated that the clearance of immune complexes by liver and spleen led to reduced deposition in the kidneys.Citation9

Cardiac device infections (CDIs) can present in the pacemaker pocket, blood stream, or as endocarditis. Endocarditis in this context is difficult to diagnose and occurs in approximately 10% of all cases.Citation10 The European Society of Cardiology recommends that all patients with an unexplained fever and implantable cardiac device be investigated for endocarditis with at least three sets of blood cultures and echocardiography.Citation11 Management with medical therapy alone is associated with higher relapse ratesCitation12 and mortality rates of 31–66% compared with 13–21% when the device is explanted.Citation13 Thus, complete device removal with antibiotic therapy guided by the organism and antibiotic sensitivities is the standard of care. Most patients should wait days to weeks before reimplantation to reduce the risk of reinfection.

Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci cause most CDIs.Citation14 Rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM) rarely cause CDIs, with only 12 other reported cases in the literature (2 Mycobacterium abscessus, 8 M. fortuitum, 1 Mycobacterium mageritense, and 1 mixed Mycobacterium chelonae and M. fortuitum infections).Citation15,16 A pacemaker pocket infection was present in all cases; half had accompanying systemic features, five (42%) had involvement of the pacemaker leads, five (42%) had bacteremia, and one patient (8%) had myocardial abscess. Only one patient had a lead-tip vegetation from which AAFB were identified. Fluoroquinolone and macrolide antibiotics were used to treat most infections. This empirical combination is prudent in most cases as RGMs are generally resistant to standard antituberculosis drugs and definitive treatment should be guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. The pacemaker system was removed in 10 cases (83%) with median treatment duration of 6 months. The American Thoracic Society recommends that RGM infections should be treated for at least 4 months with device removal to improve cure rates.Citation17

The association between mycobacterial infection and vasculitis has been noted in several case reports but these largely involve a cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) in the context of tuberculosis. There are two case reports of vasculitis associated specifically with M. fortuitum: the first was a cutaneous LCV in a previously immunocompetent hostCitation18 and the second was a pulmonary vasculitis with interstitial pneumonitis in a child treated with chemotherapy for Wilms’ tumor, with a probable intravascular infection from an indwelling central venous catheter.Citation19 We believe that our case is therefore the first report of pauci-immune ANCA-negative necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis in the context of M. fortuitum infection.

It is likely that the chronic infection caused the immune disorder that resulted in the renal disease. This case illustrates the importance of maintaining a high clinical suspicion for occult sepsis in patients who present with a history of fever and pauci-immune necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis in whom an implantable cardiac device is present. These patients should be thoroughly investigated and treated prior to commencing immunosuppressive therapy. Clinicians should beware the simultaneous use of immunosuppressive and antimicrobial therapy if the initial diagnosis is unclear to avoid precipitating overwhelming sepsis and its accompanying complications.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Albouaini K, Mudawi J, Pyatt J, Wright D. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator: What a hospital practitioner needs to know. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(6):591–597.

- Klug D, Balde M, Pavin D, . Risk factors related to infections of implanted pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators: Results of a large prospective study. Circulation. 2007;116(12):1349–1355.

- Howie AJ, Ferreira MA, Adu D. Prognostic value of simple measurement of chronic damage in renal biopsy specimens. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(6):1163–1169.

- Majumdar A, Chowdhary S, Ferreira MAS, . Renal pathological findings in infective endocarditis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(11):1782–1787.

- Raoult D, Casalta JP, Richet H, . Contribution of systematic serological testing in diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(10):5238–5242.

- Eisenberger U, Fakhouri F, Vanhille P, . ANCA-negative pauci-immune renal vasculitis: Histology and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1392–1399.

- Chen M, Feng Y, Wang S-X, . Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-negative pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:599–605.

- Kain R, Exner M, Brandes R, . Molecular mimicry in pauci-immune focal necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Nat Med. 2008;14(10):1088–1096.

- Agarwal A, Clements J, Sedmak DD, . Subacute bacterial endocarditis masquerading as type III essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8(12):1971–1976.

- Arber N, Pras E, Copperman Y, . Pacemaker endocarditis: Report of 44 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1994;73:299–305.

- , Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology; European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; International Society of Chemotherapy for Infection and CancerHabib G, Hoen B, . Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): The Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(19):2369–2413.

- Rundström H, Kennergren C, Andersson R, Alestig K, Hogevik H. Pacemaker endocarditis during 18 years in Göteborg. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36(9):674–679.

- Sohail MR, Uslan DZ, Khan AH, . Infective endocarditis complicating permanent pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infection. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(1):46–53.

- Chua JD, Wilkoff BL, Lee I, . Diagnosis and management of infections involving implantable electrophysiological cardiac devices. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:604–608.

- Al Soub H, Al Maslamani M, Al Khuwaiter J, El Deeb Y, Abu Khattab M. Myocardial abscess and bacteremia complicating Mycobacterium fortuitum pacemaker infection: Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(11):1032–1034.

- Hemmersbach-Miller M, Cárdenes-Santana MA, Conde-Martel A, Bolaños-Guerra JA, Campos-Herrero MI. Cardiac device infections due to Mycobacterium fortuitum. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(3):183–185.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, . An official ATS/IDSA statement: Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(4):367–416.

- Chen HH, Hsiao CH, Chiu HC. Successive development of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, leucocytoclastic vasculitis and Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with cervical lymphadenitis caused by Mycobacterium fortuitum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(5):1096–1100.

- Al Shaalan M, Law BJ, Israels SJ, Pianosi P, Lacson AG, Higgins R. Mycobacterium fortuitum interstitial pneumonia with vasculitis in a child with Wilms’ tumor. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16(10):996–1000.