Abstract

This article describes the anuric acute renal failure (ARF) secondary to massive pericardial effusion without tamponade in an 84 year-old man. He was referred to our emergency room with progressive dyspnea and azotemia. An electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia. A two-dimensional echocardiogram confirmed the presence of severe pericardial effusion without prominent ventricular diastolic collapse and there were no changes in his vital signs. Laboratory findings showed that his blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels were 91.8 and 3.77 mg/dL, respectively. Renal ultrasonography showed no signs of hydronephrosis. Urine output did not increase in spite of giving a saline and furosemide infusion but increased immediately after pericardiocentesis with drainage. His renal function was completely restored 3 days after the procedure. A pericardial biopsy demonstrated invasion of malignant cells. We should keep in mind that pericardial effusion is one of the causes of anuric ARF, although it is not accompanied by tamponade.

INTRODUCTION

Pericardial effusion occurs under various clinical conditions, including trauma, tumor, infections, collagen vascular disease, and metabolic disorders.Citation1,2 Hemodynamically significant pericardial effusion can cause a decrease in cardiac output and blood pressure; it can theoretically reduce renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and cause prerenal azotemia.Citation3 Seven cases of acute renal failure (ARF) associated with pericardial effusion have been reported.Citation4–8 However, ARF occurred with pericardial effusion without tamponade in only one case among them.Citation8 We describe additional case of pericardial effusion without tamponade leading to anuric ARF that completely reversed after pericardiocentesis.

CASE REPORT

An 84 year-old man was referred to our emergency room with progressive dyspnea on exertion and azotemia. The patient was previously healthy. His medical history was not notable for hypertension, diabetes, and tuberculosis. He had an 80 pack-year history of smoking, but otherwise had an unremarkable history. He had no occupation and denied current medication or a history of exposure to toxic materials.

On physical examination, he had an acute ill-looking appearance with blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg with no orthostatic change. He was afebrile and his heart rate was 102 beats/min and respiratory rate was 22 breaths/min. There were mild distended neck veins but no signs of pulsus paradoxus. His oral mucosa was mildly dried and his heart beats were rapid but had a regular rate and rhythm without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. An abdominal examination was normal without any fluid or organomegaly. The extremities did not show pitting edema, cyanosis, or clubbing. Oxygen saturation was 95% on room air.

Initial laboratory findings showed the following results: blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 91.8 mg/dL; serum creatinine, 3.77 mg/dL; serum sodium, 129.4 mmol/L; potassium, 6.9 mmol/L; bicarbonate, 8 mmol/L; calcium, 7.5 mg/dL; phosphorus, 6.5 mg/dL; total protein, 6.4 g/dL; and albumin, 3.5 g/dL. A complete blood count showed a white blood cell count of 10.28 ×103/mm3, and hemoglobin and hematocrit were 12.2 g/dL and 36%, respectively. The platelet count was 161 × 103/mm3. Thyroid function tests, including thyroid-stimulating hormone (1.64 mIU/L) and free thyroxine (1.14 ng/dL), were within the normal range. We initially could not check urine chemistry, as no residual urine was available for analysis. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia. Despite insertion of a Foley catheter, we could not collect any urine. Renal ultrasonography showed no signs of hydronephrosis but indicated a collapsed bladder without urine. The patient was initially thought to have renal failure resulting from volume depletion; thus, we infused normal saline during the initial 6 h at 200 cc/h followed by furosemide injection, but the patient remained anuric.

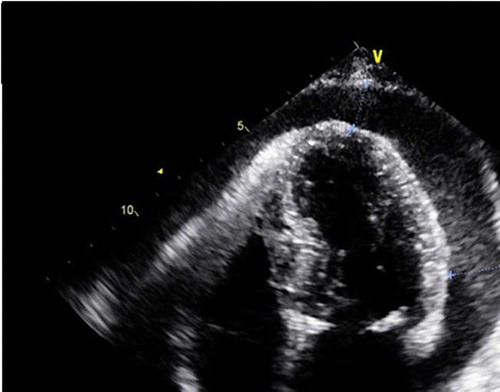

A chest radiograph showed large and globular heart (). A two-dimensional echocardiogram confirmed pericardial effusion without impending cardiac tamponade to show impaired diastolic filling of cardiac chamber and with normal systolic function (). We suspected that his ARF was due to pericardial effusion; so we conducted emergent pericardiocentesis, placed a drainage tube, and performed a pericardial biopsy. As a result, 300 mL of bloody pericardial fluid was removed. Immediately after the pericardiocentesis, urine output increased to about 2 L over the next several hours. The next day, urine output increased to 4015 mL. BUN and serum creatinine improved over the next 3 days to 25.6 and 0.88 mg/dL, respectively (). During the following 7 days, his urine output was normalized to 900 mL/day, and his blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg. He was finally diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer and malignant pericardial effusion. He denied further treatment for his lung cancer due to his old age.

Table 1. Clinical and laboratory changes before and after pericardiocentesis.

Figure 2. A two-dimensional echocardiogram showing large pericardial effusion around the whole heart with a thickness of 16–19 mm and no diastolic collapse.

We should remember that severe pericardial effusion is a cause of anuric ARF, although it was not accompanied by cardiac tamponade and that a pericardiocentesis should be conducted urgently for diagnosis and treatment.

DISCUSSION

ARF secondary to severe congestive heart failure originates from reduced renal perfusion, leading to reduced GFR. Worsening of heart failure per se is a common cause of prerenal azotemia. Pericardial effusion can also cause decreased cardiac output, low blood pressure, and heart failure.Citation6 Although pericardial effusion is suspected to induce ARF, few reports of pericardial effusion associated with ARF are available.Citation4–8

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition in which a large volume of blood or other fluid inside the pericardial sac around the heart interferes with heart performance. A diagnosis of cardiac tamponade is usually based on the clinical presentation and physical findings and is confirmed by echocardiography and cardiac catheterization,Citation7 although echocardiography is not always sensitive enough to detect clinical tamponade.Citation8 No evidence of cardiac tamponade in terms of clinical setting including absence of hypotension, pulsus paradoxus, distant heart sound on auscultation, and no QRS change on ECG in our patient. No ventricular collapse occurred during the diastolic period, and no abnormality in systolic function was observed on echocardiography. Except for one case,Citation8 six cases of ARF associated with pericardial effusion in the English literature had a hemodynamic collapse resulting from cardiac tamponade.

The exact mechanism of ARF resulting from pericardial effusion without tamponade cannot be clearly explained. Previous reports have shown that increasing the pericardial pressure by 5 mmHg decreases urinary sodium excretion and increases the renin secretion rate without changing the mean arterial pressure, renal blood flow, or GFR. A further increase in pericardial pressure to 10 mmHg decreases urinary sodium excretion and mean arterial pressure and GFR.Citation9 These results partially explain that the small increase in pericardial pressures caused by pericardial effusion, even if without overt cardiac tamponade to decrease systemic hypotension, might change renal hemodynamics leading to reduced GFR and oliguric ARF.

Because of its rareness, diagnostic criteria for pericardial effusion associated with ARF are not well established. All reported cases have shown that pericardial effusion with or without pericardial tamponade changes renal hemodynamics, resulting in oliguric or anuric azotemia. Oliguria or anuria completely recovers after decompression of the pericardial effusion and improving the azotemia.Citation4–8 These results suggest that the clinical presentation and laboratory findings are sufficient to diagnose pericardial effusion associated with ARF. Only one report showed ARF accompanying pericardial effusion without cardiac tamponade.Citation8 In that report, ARF was initially caused by the pericardial effusion. However, pericardial effusion was assumed to be the etiology of ARF after systemic hypotension due to cardiac tamponade that occurred later. Our patient definitely did not show pericardial tamponade because we initially suspected that the ARF resulted from pericardial effusion; thus, the pericardiocentesis was performed early.

We should consider severe pericardial effusion with or without cardiac tamponade as an etiology of anuric ARF, and appropriate decompression procedures should be conducted immediately to manage ARF.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- Corey GR, Campbell PT, Van Trigt P, . Etiology of large pericardial effusions. Am J Med. 1993;95:209–213.

- Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, . Incidence of specific etiology androle of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardio. 1995;75:378–382.

- Reddy PS, Curtiss EI, Uretsky BF. Spectrum of hemodynamic changes in cardiac tamponade. Am J Cardio. 1990;66:1487–1491.

- Ramsdale DR, Kaul TK, Coulshed N. Primary immungococcal pericarditis with tamponade. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61: 1067–1068.

- Queffeulou G, Vrtovsnik F, Mignon F. Acute renal failure and hepatic failure: Do not miss pericardial tamponade!. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2260–2263.

- Saklayen M, Anne VV, Lapuz M. Pericardial effusion leading to acute renal failure: Two case reports and discussion of pathophysiology. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:837–841.

- Giljaca V, Mavrić Z, Zaputović L, . Acute renal failure due to pericardial tamponade in a 60-year-old male patient. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009;43:509–511.

- Gluck N, Fried M, Porat R. Acute renal failure as the presenting symptom of pericardial effusion. Intern Med. 2011;50:719–721.

- Osborn JL, Lawton MT. Neurogenic antinatriuresis during development of acute cardiac tamponade. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:H195–H201.