Abstract

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS) is due to gain-of-function mutations in the cryopyrin gene, which determines an overactive inflammatory response. AA amyloidosis is a complication of this syndrome.

A 53-year-old man was referred to us because of lower limb edema. Past history: at the age of 20, he complained of arthralgia/arthritis and bilateral hypoacusis. At the age of 35, he presented posterior uveitis, several episodes of conjunctivitis, and progressive loss of visual acuity. Laboratory tests disclosed nephrotic syndrome, and renal biopsy showed AA amyloidosis. He was given anakinra with improvement of arthritis. A genetic study revealed the p.D303N mutation in the cryopyrin gene, and he was diagnosed as having AA amyloidosis due to CAPS. Twenty-one months after starting anakinra, the arthritis has disappeared, although nephrotic-range proteinuria persisted.

It is important to be aware of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome because it can cause irreversible complications, and there is effective therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Cryopyrin is a protein that forms part of a multiprotein complex called inflammasome. This complex, the intracellular equivalent of Toll-like receptors, is part of the innate immune system. Mutations in the gene (NLRP3, former CIAS1) coding cryopyrin underlie cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS), a monogenic auto inflammatory disorder characterized by an overactive inflammatory response in the absence of autoantibodies or specific T lymphocytes. CAPS consists of three phenotypes increasing in severity: familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle Wells syndrome (MWS), and chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous articular syndrome (CINCA/NOMID).Citation1–3 Reactive AA amyloidosis is a severe complication of CAPS.

We describe a patient with nephrotic syndrome and AA amyloidosis due to CAPS.

CASE REPORT

A 53-year-old man was referred for occasional lower limb edema that had increased over the preceding days.

Past history: Onset of arthralgia and arthritis, at the age of 20 years, in elbows, wrists, knees, and ankles, was treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Onset of bilateral hypoacusis at the same time had progressed to the point of requiring hearing aids. Since the age of 35, the patient has presented one episode of posterior uveitis and several episodes of conjunctivitis, being subsequently diagnosed with severe myopia; visual acuity has progressively worsened since then. Physical examination revealed: afebrile, blood pressure (160/80 mm Hg), clubbing of the fingers, rales at the base of both lungs, and lower limb edema, extending to the knees.

Laboratory tests disclosed: fibrinogen 1124 mg/dL (normal values (nv) 150–500), hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL (nv 13–17), leukocytes 12,460/mm3 (nv 4000–11,000), neutrophils 10,600/mm3 (nv 2000–7200), platelets 830,000/mm3 (nv 130,000–450,000), urea 122 mg/dL (nv 19–43), creatinine 3.50 mg/dL (nv 0.66–1.25), uric acid 9.8 mg/dL (nv 2.5–8.5), corrected calcium 9.12 mg/dL (nv 8.40–10.20), phosphate 6.9 mg/dL (nv 2.5–4.5), potassium 6.1 mEq/L (nv 3.5–5.10), chloride 109 mEq/L (nv 98–107), bicarbonate 17.3 mEq/L (nv 23–28), albumin 2.60 g/dL (nv 3.50–5), GT 214 U/L (nv 15–73), and alkaline phosphatase 507 U/L (nv 38–126). Other basic hematology and coagulation tests were within normal limits. C-reactive protein was 228.1 mg/L (nv < 5) and IgG was 1570 mg/dL (nv 680–1530). The following were normal/negative: IgA, IgM, C3-C4, RF, Ac anti-CCP, ANA, Ro, LA, RNP, ANCA, anti-GBM, TSH, and anti-TPO. High-resolution serum and urine electrophoresis did not reveal monoclonal components. Twenty-four- h proteinuria was 5.30 g (nv <0.15 g) with a non-selective glomerular pattern, urinary sediment: 20–30 leukocytes/HPF and granular casts, urine culture was negative.

HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBs, HCV Ab, HIV, RPR, and Quantiferon test were negative. Chest x-ray disclosed bilateral pleural effusion. X-ray of elbows, wrists, and knees showed no significant findings; x-ray of the ankles revealed a non-aggressive periosteal reaction in tibia and fibula (). The abdominal ultrasound, ECG, and echocardiogram were all normal. CT scan of the brain showed cortical cerebral atrophy.

Figure 1. Anteroposterior radiographs of both ankles showing: Left: Non-aggressive periosteal reaction in left tibia and right tibia and fibula. Right: Improvement after anakinra therapy.

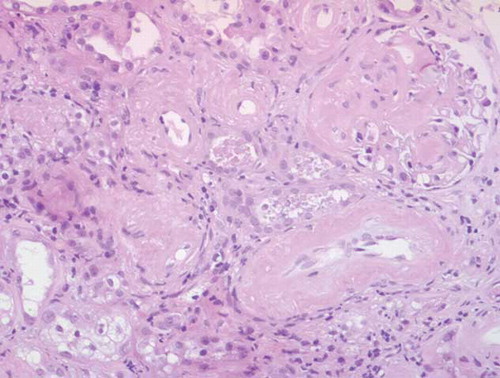

Figure 2. Light microscopy. Amyloid deposits in glomerulus (nodular mesangiocapillary pattern) and vascular walls (HE ×10).

Diagnostic thoracentesis, according to Light’s criteria and gradient of protein between serum and pleural fluid, was consistent with exudate (adenosine deaminase 16 IU/L (nv < 40); PCR for tuberculosis DNA, cultures, and cytology were negative). Percutaneous kidney biopsy (20 glomeruli) showed deposits of amorphous hyaline material in glomeruli and vessel walls (); the deposits were Congo red positive and apple green birefringent under polarized light; immunohistochemical testing was positive for AA amyloid; there were also isolated interstitial foci of inflammatory cells; interstitial fibrosis in 10% of the sample.

Given the combination of AA amyloidosis, polyarthritis, and hearing loss, the possibility of an auto-inflammatory syndrome was considered. The patient received conservative treatment for the nephrotic syndrome. He developed polyarthritis with functional impotence and intense pain. He was started on a 2-week course of prednisone (40 mg/day), and then tapered, and colchicine (1 mg/day). The polyarthritis did not improve, but creatinine levels fell to 1.40 mg/dL. Empirical therapy with anakinra (100 mg/day) was started, followed by rapid clinical improvement (relief from pain and walking with a stick), and C-reactive protein fell to 20 mg/L; chest x-ray was normal.

A genetic study revealed the p.D303N mutation in NLRP3, exon 3, in a heterozygous state.

The patient was questioned again specifically about fever or skin lesions, but denied the presence of either. He had no family history of nephropathy and fever or arthritis; his father died at 37 of liver cancer, his mother died at 80, and one brother died at 45 from a head injury.

Twenty-one months after starting anakinra therapy the arthritis has disappeared, and the periosteal reaction has improved. Kidney function remained stable (eGFR, CG/MDRD-4, around 45 mL/min/1.73 m2), nephrotic-range proteinuria persisted, and C- reactive protein ranges from 10 to 30 mg/L.

DISCUSSION

Cryopyrin activation in the inflammasome complex determines pro-caspase activation to caspase 1, which in turn determines the conversion of pro-IL-1beta and pro-IL-18 to IL-1beta and IL-18, respectively, which are essential to the inflammatory response.1 NLRP3 gene mutations are usually located in exon 3 of the NACHT domain and transmission is autosomal dominant, although it can also be sporadic.Citation2,Citation4,Citation5 These are gain-of-function mutations and involve constitutive cryopyrin activation, which causes a sustained and uncontrolled inflammatory response. A single mutation can cause different clinical phenotypes, probably due to the action of modifier genes and environmental factors.Citation1,Citation6,Citation7

FCAS is characterized by self-limited episodes of fever and rash (urticaria-like) caused by exposure to cold, but generally with no amyloidosis or hearing loss.Citation1MWS usually starts in infancy, generally with a family history, with recurrent, rarely sustained, episodes of fever, rash, arthralgia/arthritis, conjunctivitis/uveitis; 25% of cases present AA amyloidosis and 70% have sensorineural hearing loss.Citation1,Citation4

CINCA syndrome presents in the neonatal period, generally with no family history, and follows a chronic course with almost permanent symptoms. Central nervous system disorders (headache, aseptic meningitis, cerebral atrophy, and intracranial hypertension) are frequent. Two-thirds of the patients present arthralgia/arthritis, while the remainder develops a severe arthropathy due to overgrowth of the patella and epiphyses of the long bones. They also present fever, rash, anterior and posterior uveitis, progressive vision loss, sensorineural hearing loss from infancy, and AA amyloidosis.Citation3,Citation6,Citation8

Today, CAPS is considered to be a continuous spectrum of clinical manifestations rather than three separate phenotypes.Citation9 Our patient presents manifestations of CINCA (no family history, almost continuous arthritis, periosteal reaction, and cerebral atrophy) and MWS (onset relatively late in adult life); clubbing fingers, AA amyloidosis, and sensorineural hearing loss occurs in both, although onset of hearing loss is earlier in the case of CINCACitation3. An atypical feature of this case is the lack of rash.

A genetic study of this patient revealed the p.D303N mutation that consists in a G907A transition in DNA sequence by which aspartic acid is replaced with asparagine in the peptid chain.Citation8,Citation10 This mutation has been described in MWS, CINCA, and MWS/CINCA overlap;4–6,8,9,11 we believe our patient fits the latter profile.

In this case, we observed bilateral exudative pleural effusion. Serositis is not typically associated with CAPS, although pericarditis has been described in MWS with E311K mutation.Citation12 The possibility of this being merely incidental or due to a false positive exudate cannot be ruled out.

The inflammatory response in CAPS increases hepatic synthesis of SAA, a precursor of AA amyloid. In addition to increased SAA, the SAA1 genotype confers susceptibility to amyloidosis. MWS and CINCA are highly amyloidogenic,Citation13 although they are a rare etiology of AA amyloidosis. The Lachmann et al. series of 374 patients with AA amyloidosis revealed that CAPS (MWS) was the underlying condition in only four of them.Citation14 In our patient, kidney function improved after corticosteroid administration, which might suggest NSAID-induced interstitial nephritis. Kidney expression of NLRP3 increases in acute and chronic kidney disease, and IL-1 beta and IL-18 can cause renal fibrosis, suggesting that cryopyrin-inflammasome activation could cause kidney damage.Citation15

Currently, IL-1 blocking drugs (anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab) have replaced corticosteroids and NSAIDs in the treatment of CAPS with good results. Anakinra, a recombinant homologue of the human IL-1 receptor antagonist, is initially administered at a dose of 100 mg/dayCitation13 or 1 mg/kg/day,Citation16 although higher doses have been used in resistant cases.Citation16,Citation17 Anakinra is eliminated through the kidneys; and with severe kidney failure, dosage should be adjusted to 100 mg on alternate days; for clearance similar to that of our patient, elimination of anakinra through the kidney is reduced by 70%–75%.Citation18 The most common adverse effect is injection site reaction,Citation19 and infections and neutropenia have also been described; and experience is limited to five years.Citation17,Citation20 This patient presented a partial response to anakinra,Citation21 as was the case with 34% of the patients on the Euro fever Registry;Citation22 C-reactive protein presents fluctuations similar to those already described by other authors.Citation23 The partial response in our case could be due to starting treatment 30 years after onset of the disease.

To sum up, CAPS can have serious complications and should be diagnosed as rapidly as possible before irreversible damage occurs, because effective therapy is available. CAPS should be considered in patients with AA amyloidosis and arthritis, hearing loss, and eye or skin abnormalities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Dr. J.I Aróstegui (Servicio de Immunología, Hospital Clínico de Barcelona).

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Neven B, Prieur AM, Quartier dit Maire P. Cryopyrinopathies: update on pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:481–489.

- Henderson C, Goldbach-Mansky R. Monogenic auto inflammatory diseases: new insights into clinical aspects and pathogenesis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:567–578.

- Goldbach-Mansky R. Current status of understanding the pathogenesis and management of patients with NOMID/CINCA. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13:123–131.

- Dodé C, Le Dû N, Cuisset LNew mutations of CIAS1that are responsible for Muckle-Wells syndrome and familial cold urticaria: a novel mutation underlies both syndromes. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1498–1506.

- Kümmerle-Deschner JB, Tyrrell PN, Reess FRisk factors for severe Muckle-Wells syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3783–3791.

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah MDe novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrin-associated auto inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3340–3348.

- Aksentijevich I, Putnam CD, Remmers EFThe clinical continuum of cryopyrinopathies: novel CIAS1 mutations in North American patients and a new cryopyrin model. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1273–1285.

- Feldmann J, Prieur AM, Quartier PChronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome is caused by mutations in CIAS1, a gene highly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells and chondrocytes. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:198–203.

- Aróstegui JI, Aldea A, Modesto CClinical and genetic heterogeneity among Spanish patients with recurrent auto inflammatory syndromes associated with the CIAS1/PYPAF1/NALP3 gene. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:4045–4050.

- Aróstegui JI. Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: genetic and molecular basis and the inflammasome). Med Clin (Barc). 2011;136(Suppl. 1):22–28.

- Granel B, Philip N, Serratrice JCIAS1 mutation in a patient with overlap between Muckle-Wells and chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndromes. Dermatology. 2003;206:257–259.

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Lohse P, Koetter INLRP3 E311K mutation in a large family with Muckle-Wells syndrome–description of a heterogeneous phenotype and response to treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R196.

- Leslie KS, Lachmann HJ, Bruning EPhenotype, genotype, and sustained response to anakinra in 22 patients with auto inflammatory disease associated with CIAS-1/NALP3 mutations. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1591–1597.

- Lachmann HJ, Goodman HJ, Gilbertson JANatural history and outcome in systemic AA amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2361–2371.

- Vilaysane A, Chun J, Seamone METhe NLRP3 inflammasome promotes renal inflammation and contributes to CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1732–1744.

- Neven B, Marvillet I, Terrada CLong-term efficacy of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in ten patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease/chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:258–267.

- Sibley CH, Plass N, Snow JSustained response and prevention of damage progression in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease treated with anakinra: A cohort study to determine three- and five-year outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2375–2386.

- Yang BB, Baughman S, Sullivan JT. Pharmacokinetics of anakinra in subjects with different levels of renal function. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:85–94.

- Kaiser C, Knight A, Nordström DInjection-site reactions upon Kineret (anakinra) administration: experiences and explanations. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:295–299.

- Direz G, Noël N, Guyot C, Toupance O, Salmon JH, Eschard JP. Efficacy but side effects of anakinra therapy for chronic refractory gout in a renal transplant recipient with preterminal chronic renal failure. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:631.

- Caorsi R, Federici S, Gattorno M. Biologic drugs in auto inflammatory syndromes. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:81–86.

- Ter Haar N, Lachmann H, Ozen STreatment of auto inflammatory diseases: results from the Euro fever registry and a literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:678–685.

- Lovell DJ, Bowyer SL, Solinger AM. Interleukin-1 blockade by anakinra improves clinical symptoms in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1283–1286.