Abstract

Background: Atrial fibrillation (AF) is emerging as a major health problem. The prevalence is as high as 32% in patients with renal disease. Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a frequent complication. Objective: To investigate the hazards of resumption or discontinuation of anticoagulation in renal disease patients after an episode of GIB. Design, settings, participants and measurements: This is a multicenter retrospective cohort of patients with AF on warfarin that developed an episode of GIB. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined by eGFR ≤60 mL/min and end stage renal disease (ESRD) was defined by being on hemodialysis for >3 months. Outcomes were 90-day recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB), mortality, and stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA). Results: Out of 11,513 AF patients, index GIB occurred in 96 ESRD and 159 CKD patients. Outcomes of CKD patients did not differ when compared with patients with normal kidney function. CKD patients who resumed warfarin had decreased stroke/TIA rates (p < 0.0001). There were no significant differences between CKD patients who resumed warfarin versus that did not resume warfarin (p > 0.05). ESRD patients also did not have significant differences in outcomes when compared to patients with normal kidney function restarted on warfarin. However, there was an increase in recurrent GIB and decrease in mortality as well as stroke/TIA when patients with ESRD that restarted warfarin were compared with ESRD patients who did not restart warfarin. Conclusion: Study suggests resuming warfarin after an episode of GIB in CKD patients but recommends considering the increased risk of recurrent GIB in ESRD patients.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia and currently affects 2.3 million people in United States.Citation1 Data from Medicare showed that the prevalence of AF increased from 26% in 1998 to 32% in 2005 in older patients with chronic kidney disease or end stage renal disease.Citation2 Warfarin continues to be underused with almost 51% of the patients not being on warfarin and 25% of the patients discontinued warfarin.Citation2

Chronic kidney disease itself has shown to be a predictor of incident atrial fibrillation.Citation3 Due to various comorbidities present in this population, they are also at higher risk of complications of atrial fibrillation as well as the therapy.Citation4 Patients with atrial fibrillation are at 5-fold increased risk of having a strokeCitation5 while chronic kidney disease and ESRD increase the risk of stroke by almost 4 and 6 times.Citation6

Similarly, patients with chronic kidney disease and ESRD are at higher risk of developing upper gastrointestinal bleeding that increases the mortality by 3 folds in these patients.Citation7 Atrial fibrillation patients who are anticoagulated are also at 3 folds higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.Citation8 There is currently no data available about the chronic kidney disease or ESRD patients who develop gastrointestinal hemorrhage and interrupt anticoagulation. Data is also not available in the current literature about the various reasons for not resuming anticoagulation in these patients.

This particular population is excluded from the clinical trials and due to the small numbers available, this data has not been evaluated extensively in the past. Due to increase in the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and aging population worldwide, the burden of chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation is increasing making it an important public health issue.Citation9 Various newer oral anticoagulants even though proven safer in renal disease patients,Citation10 have even higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.Citation11 Hence, warfarin may stay the main therapy for these patients. However, data are not available about the bleeding and stroke outcomes of this selective group of patients.

Hence, we aimed to analyze the bleeding and stroke outcomes of patients with chronic kidney disease and ESRD who were restarted on warfarin after a gastrointestinal hemorrhage and to evaluate the various causes of not restarting warfarin therapy in these patients.

Methods

Patients were defined to have moderate chronic kidney disease when mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was ≤60 mL/min calculated with MDRD equation over a period of 3 months prior to index gastrointestinal bleed (GIB). Patients were defined to be end stage renal disease patients if they had been on hemodialysis. Patients with peritoneal dialysis were planned to be excluded; however there were no patients in the cohort on peritoneal dialysis. Patients with renal transplantation were included also classified based on their eGFR status. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Henry Ford Health Systems, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Study population and settings

This is a retrospective cohort study at a large health system (Henry Ford Health Systems) in the south eastern Michigan that included 5 hospitals and 32 clinics serving all strata of socioeconomic status from January 2005 to December 2010.

Data sources

Data were obtained from the insurance claims for warfarin for patients who were seen at anticoagulation clinic at Henry Ford Health Systems, Detroit, Michigan. Information on demographics, medication use, and other clinical variables was obtained by detailed chart reviews. The evaluation of patients was first performed on admission and then after resolution of gastrointestinal bleeding defined by stability of hemoglobin for 24–48 hours. CHADS2 and HAS–BLED scores were calculated at this time for these patients.Citation12,Citation13 Complete chart review and follow up of the patients was performed as the data were available through the warfarin anticoagulation clinic and hospital notes. Estimated GFR was calculated based on the MDRD equation:Citation14

CKD was considered if patient has an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of ≤60 mL/min by the above-mentioned method.

Warfarin use

Consecutive patients who were started on warfarin in the last one year and refilled warfarin at least twice within the last 90 days of gastrointestinal bleeding in whom the primary reason for anticoagulation was non-valvular atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they were on other long-term anticoagulants, but were included if they were on aspirin, NSAIDs or other antiplatelet agents. The study protocol was approved by institutional review board.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 1-year major gastrointestinal bleeding risk and 1-year thromboembolic risk in patients with CKD and ESRD.

Secondary outcomes were 1-year mortality, 1-year GIB risk, time to resume anticoagulation, stroke related mortality, gastrointestinal bleeding related mortality. Outcomes were adjudicated by two blind reviewers (F.K. and S.H.) for stroke, TIA, and major gastrointestinal bleeding. These were then rechecked and conflicts were resolved by consensus. Mortality data were obtained from social security death index.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed in mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were provided in percentages. Differences were analyzed using two sample t-tests for continuous variables and the Fisher Exact test or Chi-square, when appropriate. Patients who were restarted on warfarin and had CKD and ESRD were first compared with patients with normal kidney function that were restarted on warfarin. The same group of patients was then compared with patients who did not restart warfarin and had CKD or ESRD. This comparison was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model with adjustment for propensity score, ICU stay, blood transfusions, age and gender. Time dependent covariate analysis was performed in order to take into account multiple episodes of GIB and thromboembolism. The propensity score was calculated by logistic regression for each patient the conditional probability of re-initiating warfarin. The covariates used were age, gender, race, fresh frozen plasma, vitamin K use, Charlson comorbidity index, cancer, INR at GIB, time within therapeutic range prior to GIB, heart failure, aspirin, NSAIDs and clopidogrel use. Kaplan Meier’s curves were also constructed for groups given above for the outcomes of mortality, recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding and thromboembolism.

Results

A total of 1329 patients developed gastrointestinal hemorrhage within one year of restarting warfarin. There were 159 (12.0%) patients with chronic kidney disease and 96 (7.2%) patients with end stage renal disease. Patients with CKD were more likely to be younger, hypertensive, higher HAS–BLED scores, previous episodes of GIB, CAD, and had upper GIB as compared to patients with normal kidney disease. Patients with ESRD were more likely to be older, diabetic, hypertensive, higher HAS–BLED scores, have previous GIB, and had history of previous stroke/TIA. Baseline characteristics are shown in .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patient population.

Warfarin was restarted in 89 (56%) CKD patients and 34 (35.4%) ESRD patients. There were 77 (48.4%) deaths in CKD patients and 51 (53.1%) deaths in ESRD patients. There were 32 (20.1%) CKD patients who developed recurrent GIB and 19 (19.8%) ESRD patients developed recurrent GIB within 90 days. While, 49 (30.8%) CKD patients and 26 (27.0%) ESRD patients had a recurrent GIB episode within a year. Stroke/TIA occurred in 31 (21.4%) patients in CKD group and 22 (22.9%) patients in ESRD group.

Time to restart warfarin was 48.3 ± 31.7 for patients with CKD and 49.1 ± 43.5 days for ESRD patients. This was not significantly different from the patients without renal disease. There was 1 death that occurred secondary to GIB in CKD group and 1 in ESRD group. There was only 1 death secondary to stroke/TIA in Warfarin was discontinued within 1 year in 35 (23%) of CKD patients and 20 (20.8%) of ESRD patients. Patients who were not restarted on warfarin initially were restarted on warfarin in 13 (8.2%) CKD patients and 5 (5.2%) ESRD patients.

Chronic kidney disease

There were159 patients with chronic kidney disease, out of which 32 (20.1%) patients developed recurrent GIB within 90 days. The annual risk of recurrent GIB was 49 (30.8%). Restarting warfarin was not associated with higher hazard of recurrent GIB (HR 1.00; 95% CI 0.51–2.00, p = 0.98) when compared to patients with normal kidney function that were restarted on warfarin. However, there was trend towards increased hazard of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding when compared with CKD patients who were not restarted on warfarin (HR 2.50; 95% CI 0.85–7.28, p = 0.095).

There was also no difference in thromboembolism when warfarin was when compared with patients with normal kidney function that were restarted on warfarin (HR 0.97; 95% CI 0.71–1.33, p = 0.86). However, there was a significant better outcomes when these patients were compared with CKD patients who were not restarted on warfarin (HR 0.06; 95% CI 0.02–0.16, p < 0.0001) in terms of thromboembolic outcomes.

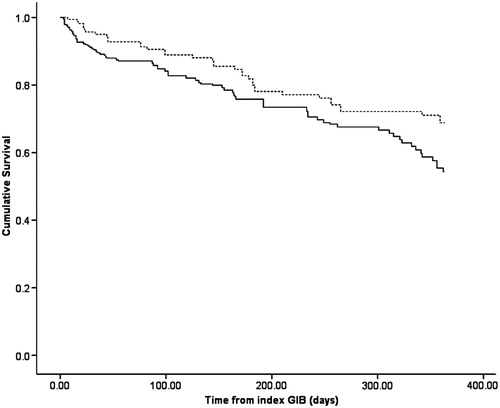

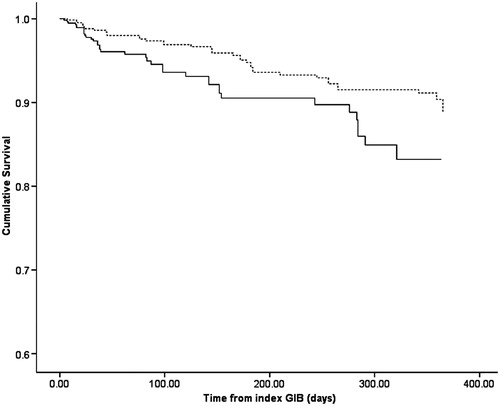

There was no decrease in mortality between CKD and patients who were not restarted on warfarin (HR 1.06; 95% CI 0.96–1.15, p = 0.25) while there was a trend toward decrease in mortality in patients with CKD who were restarted on warfarin compared to patients who were not restarted on warfarin (HR 0.70; 95% CI 0.46–1.07, p = 0.10), as shown in . demonstrate the survival analysis of CKD patients who restarted warfarin versus normal patients who were restarted on warfarin. shows the survival analysis of CKD patients who restarted warfarin versus CKD patients who did not restart warfarin.

Figure 1. Kaplan Meier’s survival curve of patients who were restarted on warfarin with normal kidney function (broken line) and chronic kidney disease patients (solid line).

Figure 2. Kaplan Meier's survival curve of patients with chronic kidney disease that were restarted on warfarin (broken line) versus chronic kidney disease patients who were not restarted on warfarin (solid line).

Table 2. Risk of various outcomes in CKD patients.

End stage renal disease

There were 96 patients with ESRD in the cohort who developed gastrointestinal bleeding. Out of these, 26 (27.1%) developed recurrent GIB within first year. There were 19 (19.8%) patients with recurrent GIB within first 90 days of restarting warfarin. The risk of recurrent GIB was not higher when compared with patients with normal kidney function that restarted warfarin (HR 1.12; 95% CI 0.99–1.26, p = 0.07). The recurrent risk of GIB was higher for ESRD patients who were restarted on warfarin versus ESRD patients who were not restarted on warfarin (HR 1.72; 95% CI 1.29–2.30, p < 0.0001).

The risk of thromboembolism was reduced when warfarin was restarted in ESRD patients compared with ESRD patients not restarted on warfarin (HR 0.44; 95% CI 0.27–0.73, p = 0.002) while the decrease in the risk of thromboembolism was not different from the normal kidney patients who restarted warfarin (HR 0.70; 95% CI 0.45–1.1, p = 0.12).

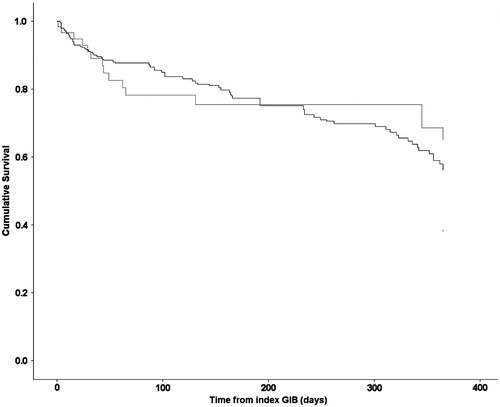

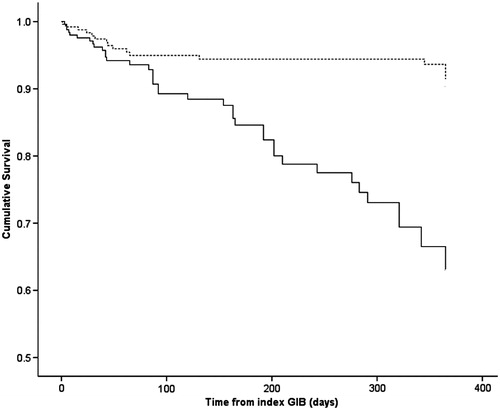

The mortality risk was also not different from patients with normal kidney function that restarted warfarin (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.52–1.14, p = 0.19) and was better than ESRD patients who did not restart warfarin (HR 0.22; 95% CI 0.13–0.40, p < 0.0001) as shown in . demonstrates the survival analysis of ESRD patients who restarted warfarin versus normal patients who were restarted on warfarin. shows the survival analysis of ESRD patients who restarted warfarin versus ESRD patients who did not restart warfarin.

Figure 3. Kaplan Meier’s survival curve of patients who were restarted on warfarin with normal kidney function (broken line) and end stage renal disease patients on hemodialysis (solid line).

Figure 4. Kaplan Meier's survival curve of patients with end stage renal disease patients on hemodialysis that were restarted on warfarin (broken line) versus end stage renal disease patients on hemodialysis that were not restarted on warfarin (solid line).

Table 3. Risk of various outcomes in ESRD patients.

Discussion

In our study, we demonstrated that restarting warfarin in both CKD patients as well as ESRD provides benefit in terms of preventing subsequent thromboembolic event with a significant increase in risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in only in ESRD patients but not CKD patients. We also showed that there was no additional benefits over the normal population that was restarted on warfarin but the main benefits are in the renal disease population that was not restarted on warfarin. Also, another highlight of the study is the huge treatment gap in a multicenter setting of these elderly patients who are not restarted on warfarin therapy after an episode of gastrointestinal bleeding exposing them to a higher risk of thromboembolism.

Previous studies including patients with hemodialysis demonstrated either no benefitsCitation15−17 or harmful effectsCitation18 from warfarin. Our study also demonstrates no benefits of using warfarin in patients when compared with patients with normal renal function, rather there is a higher risk of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding however most of the bleedings in our population were self-limiting and only two patients had a gastrointestinal bleeding related death. We did find a statistically significant higher number of blood product transfusion in this group of patients (data not shown), particularly because these patients have impaired renal erythropoietin formation, and hence requiring longer lengths of stay due to blood transfusions.Citation19 However, when the analysis was adjusted for length of stay, intensive care unit stay, blood product transfusion, and vitamin K use, the associations did not differ. This study recommends considering risks and benefits prior to reinitiating warfarin in End stage renal disease patients since re-initiation is also leading to increase in recurrent GIB, which most probably will increase the cost and health care utilization.Citation20

On the other hand, our study showed only trends towards increased bleeding and decreased mortality in patients who resumed warfarin therapy, but a significant decrease in thromboembolism when compared with CKD patients not restarted on warfarin. There were no significant differences in the outcomes when compared with normal patients. This is particularly interesting since it implies in a way that the bleeding complications are more severe in ESRD patients. This conferred with the findings from a large observational study.Citation7 Uremia was long thought as one of the most important reasons for bleeding in renal disease patients.Citation21,Citation22 However, even with adjustment of uremia in our study population ESRD continued to have a higher degree of recurrent GIB. This brings forth the other hemostatic mechanisms that kidneys might play even when there is some degree of renal disease.Citation23 Furthermore, ESRD patients are routinely exposed to heparin used to prevent thrombosis in the extracorporeal hemodialysis circuit that might also lead to this accentuation of recurrent GIB.Citation24

Chan et al. previously demonstrated in a large study of hemodialysis patients that warfarin use in ESRD may actually lead to increase in strokes.Citation25 Even though counterintuitive, they explained these findings on the basis of warfarin leading to worsening of vascular calcification eventually leading to thromboembolism. Our findings are not in agreement with their findings and show that warfarin leads to decrease in thromboembolic episodes. Chan et al also noticed that there was higher number of strokes in patients who did not have in-facility INR monitoring.Citation25 Our patients were monitored for INR very carefully at a warfarin monitoring clinic and this might be a reason for the beneficial response of warfarin seen in our patients.

Many of our patients were also on aspirin. We found that recurrent bleeding was more common in patients on aspirin. However, there was no statistically significant difference in any of the population subgroups when compared with each other. This is probably because of small sample size of the patients but does propose that aspirin use might be safe in patients with very high CHADS2 scores and low HAS – BLED scores. This is in line with the findings of a recent meta-analysis in which use of antiplatelet medications did not worsen the outcomes.Citation26 Future studies might be required to investigate the effects of aspirin and warfarin combination in renal disease patients.

The event rates for thromboembolism in our population were significantly higher than the original CHADS2 observational cohort.Citation12 This may be explained by the pro-coagulant milieu in patients with renal disease. These patients have higher levels of prothrombin and hence thrombin levels.Citation27 These patients also have higher comorbidity burden which may lead to poor outcomes.Citation28

There are several strengths of our study particularly the uniqueness of these patients, the robustness of the data collection strategies, the use of insurance claims and using the patients’ data from the warfarin follow up clinic. Since the data from the insurance were available, even if these patients were admitted in another hospital, their information was available thus leading to reduction in follow up bias. The data regarding the compliance was also available as well as the time in therapeutic range. This kind of fine granularity of data is usually not available via larger Medicare-based populations.Citation3,Citation29

There was a significant reduction in mortality only demon-strated in ESRD population, however there was a trend toward decreased mortality in CKD population who were restarted on warfarin. This was attributed to the beneficial cardiovascular effects of warfarin which are very similar to aspirin.Citation30,Citation31

Clinical implications

The study provides event rates for gastrointestinal bleeding and thromboembolism as well as mortality. These event rates and lack of gastrointestinal bleeding related deaths favor the use of re-initiation of warfarin in all the patients with renal disease. However, the study data suggests caution in patients with chronic kidney disease. However, the mortality benefit in these patients might be important. We suggest performing a decision analysis model study based on a similar population to answer this question in better detail. We also observed that using concomitant aspirin with warfarin did not increase the events of gastrointestinal bleeding; however, it will require a study with larger sample size with adequate power to confirm the safety.

Limitations

The retrospective design of the study as well as initial use of database search might have led to some bias, however all the patients included in the study had a detailed chart review performed afterwards. Data regarding the endoscopic evaluation, physician decision making and reasons for not resuming warfarin were not included in the study. However, due to large data size, they were quite uniform in all the patients (data not presented). We also did not perform a decision model in our study due to smaller number of patients and this could be addressed in a larger study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings suggest the re-initiation of warfarin in patients with chronic kidney disease, however in patients with end stage renal disease, a formal discussion about risks and benefits of re-initiation of warfarin should be considered due to significant increase in recurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Lip GY, Brechin CM, Lane DA. The global burden of atrial fibrillation and stroke: a systematic review of the epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in regions outside North America and Europe. Chest. 2012;142(6):1489--1498

- Winkelmayer WC, Liu J, Patrick AR, Setoguchi S, Choudhry NK. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation and warfarin use in older patients receiving hemodialysis. J Nephrol. 2012;25:341–353

- Nelson SE, Shroff GR, Li S, Herzog CA. Impact of chronic kidney disease on risk of incident atrial fibrillation and subsequent survival in medicare patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e002097 . doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.002097

- Schonburg M, Ziegelhoeffer T, Weinbrenner F, et al. Preexisting atrial fibrillation as predictor for late-time mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing cardiac surgery – a multicenter study. Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgeon 2008;56:128–132

- Laupacis A, Boysen G, Connolly S, et al. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Internal Med. 1994;154(13):1449–1457

- Collins AJ, Foley RN, Chavers B, et al. United States Renal Data System 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease & end-stage renal disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis: Official J Natl Kidney Foundation. 2012;59:A7, e1–e420

- Sood P, Kumar G, Nanchal R, et al. Chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease predict higher risk of mortality in patients with primary upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:216–224

- Coleman CI, Sobieraj DM, Winkler S, et al. Effect of pharmacological therapies for stroke prevention on major gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Clin Practice. 2012;66:53–63

- McCullough K, Sharma P, Ali T, et al. Measuring the population burden of chronic kidney disease: a systematic literature review of the estimated prevalence of impaired kidney function. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant: Official Publ Eur Dialysis Transplant Assoc – Eur Renal Assoc. 2012;27:1812–1821

- Fox KA, Piccini JP, Wojdyla D, et al. Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism with rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and moderate renal impairment. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2387–2394

- Boland M, Murphy M, McDermott E. Acute-onset severe gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage in a postoperative patient taking rivaroxaban after total hip arthroplasty: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:129

- Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001;285:2864–2870

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010;138:1093-1100

- Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Internal Med. 1999;130:461–470

- Genovesi S, Vincenti A, Rossi E, et al. Atrial fibrillation and morbidity and mortality in a cohort of long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis: Official J Natl Kidney Foundation. 2008;51:255–262

- To AC, Yehia M, Collins JF. Atrial fibrillation in hemodialysis patients: do the guidelines for anticoagulation apply? Nephrology (Carlton). 2007;12:441–447

- Wizemann V, Tong L, Satayathum S, et al. Atrial fibrillation in hemodialysis patients: clinical features and associations with anticoagulant therapy. Kidney Intl. 2010;77:1098–1106

- Nair M, Nayyar S, Rajagopal S, Balachander J, Kumar M. Results of radiofrequency ablation of permanent atrial fibrillation of >2 years duration and left atrial size >5 cm using 2-mm irrigated tip ablation catheter and targeting areas of complex fractionated atrial electrograms. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:683–688

- Pattakos G, Koch CG, Brizzio ME, et al. Outcome of patients who refuse transfusion after cardiac surgery: a natural experiment with severe blood conservation. Arch Internal Med. 2012;172:1154–1160

- Viviane A, Alan BN. Estimates of costs of hospital stay for variceal and nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the United States. Value Health: J Intl Soc Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;11:1–3

- Andrassy K, Ritz E. Uremia as a cause of bleeding. Am J Nephrol. 1985;5:313–319

- Sagripanti A, Barsotti G. Bleeding and thrombosis in chronic uremia. Nephron 1997;75:125–139

- Linne T. Prolonged bleeding time in non-uremic acute glomerulonephritis. Thrombosis Hemostasis 1979;42:1060–1061

- Sagedal S, Hartmann A, Sundstrom K, Bjornsen S, Brosstad F. Anticoagulation intensity sufficient for hemodialysis does not prevent activation of coagulation and platelets. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant: Official Publ Eur Dialysis Transplant Assoc – Eur Renal Assoc. 2001;16:987–993

- Chan KE, Lazarus JM, Thadhani R, Hakim RM. Warfarin use associates with increased risk for stroke in hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2223–2233

- Kussmaul W. Effects of antiplatelet therapy on mortality and cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes in persons with chronic kidney disease. Ann Internal Med. 2012;157:302; author reply 3–4

- Erdem Y, Haznedaroglu IC, Celik I, et al. Coagulation, fibrinolysis and fibrinolysis inhibitors in hemodialysis patients: contribution of arteriovenous fistula. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant: Official Publ Eur Dialysis Transplant Assoc – Eur Renal Assoc. 1996;11:1299–1305

- Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic disease in patients starting end-stage renal disease therapy. Kidney Intl. 1995;47:186–192

- Knight TG, Ryan K, Schaefer CP, D'Sylva L, Durden ED. Clinical and economic outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries with stage 3 or stage 4 chronic kidney disease and anemia: the role of intravenous iron therapy. JMCP. 2010;16:605–615

- Rothberg MB, Celestin C, Fiore LD, Lawler E, Cook JR. Warfarin plus aspirin after myocardial infarction or the acute coronary syndrome: meta-analysis with estimates of risk and benefit. Ann Internal Med. 2005;143:241–250

- Schreiber TL, Miller DH, Silvasi D, McNulty A, Zola BE. Superiority of warfarin over aspirin long term after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1990;119:1238–1244