Abstract

Objective: This study aims to quantify and compare the risks of death and end stage renal disease (ESRD) in a prospective cohort of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 1–5 under renal management clinic at Peking University Third Hospital and to evaluate the risk factors associated with these two outcomes. Method: This was a prospective cohort study. Finally, 1076 patients at CKD stage 1–5 short of dialysis were recruited from renal management clinic. Patients were monitored for up to Dec, 2011 or until ESRD and death. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated (eGFR) according to the using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula. Results: At the end of follow-up, 111 patients (10.1%) developed ESRD (initiated dialysis or kidney transplantation (ESRD)) and 24 patients (2.2%) had died. There were more ESRD occurrence rate in patients with baseline diabetic nephropathy, lower eGFR, hemoglobin <100 g/L and 24 h urinary protein excretion ≥3.0 g. By multivariate Cox regression model, having heavy proteinuria and CKD stage were the risk factors of ESRD. For all-cause mortality, the most common cause was cardiovascular disease, followed by infectious disease and cancer. But we failed to conclude any significant variable as risk factors for mortality in multivariate analysis. Conclusions: Our study indicated that baseline diabetic nephropathy, lower hemoglobin level, lower baseline GFR and heavy proteinuria were the risk factors of ESRD. In this CKD cohort, patients were more likely to develop ESRD than mortality, and cardiovascular mortality was the leading cause of death, and then followed by infectious diseases and cancer in this population.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a public health problem around the world. It is reported that about 11% of people or more than 20 million in the United States have CKD.Citation1 Incidence for developing CKD differs between races and countries. It would be interesting to know the incidence of CKD and its causes in China, which is a densely populated country with low income, different food, cultural traditions and lifestyle habits. Recently, a cross-sectional survey have verified that the overall prevalence of CKD in China is 10.8% (10.2–11.3),Citation2 almost the same as USA; therefore, the number of patients with CKD in China is estimated to be about 119.5 million (112.9–125.0 million). From great majority of reports in the Western countries, the risk for mortality is similar to or even more than the risk of end stage renal disease (ESRD) in the CKD population of developed countries seen by nephrologists.Citation3,Citation4 However, the progression rate of ESRD and mortality of Chinese pre-dialysis patients have not been studied well in mainland China. This study was initiated to quantify and compare the risks of mortality and ESRD in a prospective cohort of patients with CKD stages 1–5 under renal management clinic at Peking University Third Hospital and evaluated the risk factors associated with these two outcomes.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study. From August 2006 to September 2007, we consecutively screened persons with stage 1–5 CKD without dialysis from the renal clinic. CKD patients older than 18 years of age with stable renal function for at least 3 months were included while patients expecting to start dialysis or undergo renal transplantation within 6 months were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The Peking University Third Hospital Ethics Committee approved this study protocol. A total of 1211 patients were enrolled, 133 patients lost to follow-up and two patients who refused to initiate dialysis were excluded; finally, 1076 patients finished regular clinic follow-up. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated (eGFR) according to the using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula.Citation5

Female, serum creatinine (Cr) ≤61.6 µmol/L for eGFR = 144 × (Cr/88/0.7)−0.329 × (0.993)age;

Cr > 61.6 µmol/L for eGFR = 144 × (Cr/88/0.7)−1.209 ×(0.993)age;

Male, Cr ≤79.2 µmol/L for eGFR = 141 × (Cr/88/0.9)−0.411 ×(0.993)age,

Cr > 79.2 µmol for eGFR = 141 × (Cr/88/0.9)−1.209 ×(0.993)age

CKD stage was determined as described by the National Kidney Foundation of the United States. At the time of entry, GFR of >90, 60–89, 30–59, 29–15 and <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 for more than 3 months were classified as CKD stages 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

CKD was identified by a blood test for creatinine for calculating the GFR and urinary analysis, CKD stage 1, 2 needed the evidence of renal injuries, such as proteinuria, albuminuria or hematuria showed that the kidney is allowing the loss of protein or red blood cells into the urine. To fully investigate the underlying cause of kidney damage, various forms of medical imaging, blood tests and often renal biopsy are employed (222 patients were received kidney biopsy in our current study). Historically, kidney disease has been classified according to the part of the renal anatomy that is involved. Vascular, includes large vessel disease such as bilateral renal artery stenosis and small vessel disease such as hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Glomerular, comprising a diverse group and subclassified into primary glomerular disease and secondary glomerular disease such as diabetic nephropathy and lupus nephritis. Tubulointerstitial including polycystic kidney disease, drug and toxin-induced chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis and reflux nephropathy.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) included five categories in CKD patients according to KDIGO:Citation6 (1) coronary heart disease, (2) congestive heart failure, (3) cerebrovascular infarcts or hemorrhage, and (4) peripheral vascular disease, (5) sudden cardiac death.

Urinalysis of 24-h urine protein quantitative was performed with the whole day urine. We defined 24-h urinary protein excretion <0.15 g/24 h or urinary protein negative in urine strip test as no proteinuria, 0.15 g/24 h to 2.9 g/24 h as mild proteinuria, and ≥3.0 g/24 h as heavy proteinuria.

Outcome data

The observation period of each patient was defined to start immediately after the registered measurement of serum creatinine and lasted until Dec, 2011 or ESRD (initiated dialysis or kidney transplant), death. Criteria of initiation of dialysis: (1) GFR ≪10 mL/min or (2) refractory heart failure, lung edema, severe metabolic acidosis, or hyperkalemia, (3) pericarditis, (4) uremic encephalopathy, and (5) uncontrolled nausea, vomiting, or cachexia. Outcome data such as dialysis or kidney transplantation were collected by medical record. Death data were collected by renal nurse by telephone follow-up or other documentary such as certificate of habitant death.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. Comparison of continuous variables were performed using ANOVA or independent sample-t test. Categorical and nominal data were compared using the Chi-square test. The Kaplan–Meier method and K–M plot were to estimate the cumulative incidence of ESRD l disease and to add the K–M plot with information of no. at risk in each time interval and multivariable Cox regression model were performed. All analyses were performed with SPSS, version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline demographic characteristics

We studied 1076 of the 1211 patients, 135 patients were excluded because of lack of follow-up information (n = 133) and refusing initiation of dialysis (n = 2). Their baseline demographic characteristics are summarized in . At the start of the study, 52 (4.7%) patients were at stage 1, 288 (26.3%) at stage 2, 483 (44.1%) at stage 3, 157 (14.3%) at stage 4, and 115 (10.5%) at stage 5 without dialysis. 580 (53.9%) patients were male, 170 (15.7%) had CVD and 127 (11.8%) were diabetic nephropathy. More male patients were at stage 1 and 3 CKD, but percentages became opposite at CKD stage 2, 4 and 5. The most common primary etiology of CKD at all patients was likely related to glomerulonephritis, followed by hypertensive nephrosclerosis, diabetic nephropathy. But the most common primary etiology was glomerulonephritis at stage 1 and 2 CKD (82.6–80%) whereas the most common primary etiology was hypertensive nephrosclerosis at stage 3 and 4 CKD (38.7–33%). On the other hand, the most common cause of CKD was chronic interstitial nephritis (28.7%), followed by diabetic nephropathy (21.8%) and glomerulonephritis (21.8%) at CKD stage 5. Patients with stage 4 CKD had significantly higher systolic blood pressure (BP). The diastolic BP, body mass index (BMI), serum albumin, blood glucose and triglyceride levels were similar across all five CKD stages. Patients with stage 5 CKD had significantly lower hemoglobin, lower cholesterol, lower high-density lipoprotein and higher serum creatinine, when compared to patients at CKD stage 1–4.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients by CKD staging.

Three hundred thirty-seven patients for stage 1 and 2 CKD and 739 patients for CKD stage 3, 4 and 5. There was no different significance in all-cause mortality between CKD stage 1–2 CKD and CKD stage 3, 4 and 5 while there were more patients to develop ESRD in CKD stage 3, 4 and 5 than CKD stage 1 and 2.

Patient outcomes

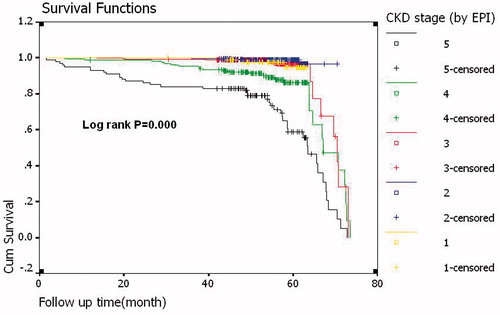

Totally 1076 patients completed the follow-up or were followed until they reached ESRD or death. The mean followed time was 55 ± 9 (months), summarizes the progression rates and clinical outcomes for patients by CKD stage. From CKD stage 1–5, progression rates to ESRD increased gradually. At the end of the study, 111 patients (10.3%) had started RRT (53 patients for hemodialysis; 54 patients for peritoneal dialysis; 4 patients for renal transplantation), and 24 patients had died (2.2%). The major causes of mortality were CVD (41.7%), followed by infectious disease (12.5%) and cancer (8.3%). Cumulative outcomes grouped by baseline stages of CKD are depicted in .

Table 2. Clinical outcomes of patients by baseline CKD stages (By CKD–EPI equation).

Table 3. Multivariate Cox regression model for the effect of base line variables on risk of ESRD.

Risk factors for ESRD (initiation of dialysis or kidney transplantation)

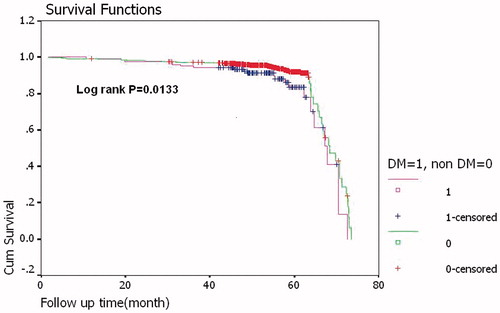

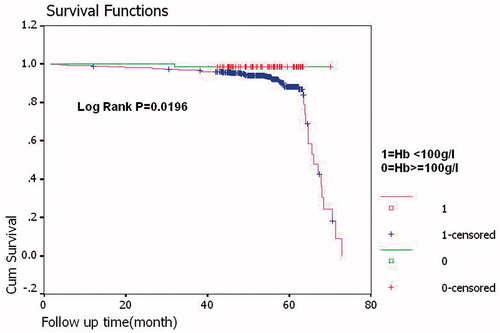

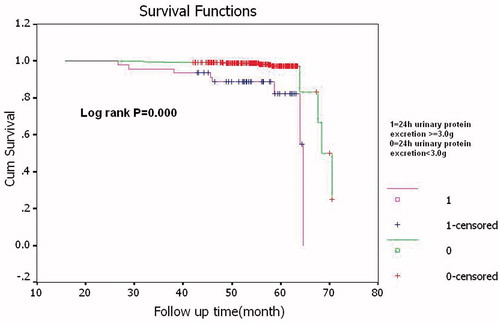

We compared with the ESRD occurrence rate by Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis (Log rank analyzed the differences). Our results showed that there were higher ESRD occurrence rate in diabetic nephropathy patients; lower eGFR (CKD stage 5 versus stage 1, 2, 3 and 4); low hemoglobin (hemoglobin <100 g/L compared with ≥100 g/L), heavy proteinuria (24 h urinary protein excretion ≥3.0 g), please see , , and . Using multivariate Cox egression model, we found heavy proteinuria and CKD stage were independent risk factor for ESRD, please see .

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier curve for ESRD occurrence rate according to CKD patients with baseline diabetic nephropathy or not.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier curve for ESRD occurrence rate according to CKD patients with baseline hemoglobin lower than 100 g/l or not.

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier curve for ESRD occurrence rate according to CKD patients with baseline 24 h urinary protein excretion ≥ 3.0 g or not.

Mean eGFR at dialysis initiation in these patients was 8.7 ± 5.2 mL/min [Median 7.1 min/mL, (5.0–10.3 min/mL) for 25th percentile–75th percentile].

Risk factors for all-cause mortality

For all-cause mortality, as there was only 24 mortality cases (death rate 2.2%), the most common cause for all-cause mortality was CVD, followed by infectious disease and cancer. Univariate analysis mortality group had higher systolic BP (141 ± 27 mmHg vs. 127 ± 19 mmHg, p = 0.048) and increased pulse pressure (63 ± 26 vs. 49 ± 16 mmHg, p = 0.014) compared with the survival group, but we failed to conclude any significant variables as predictors for mortality in multivariate analysis.

Discussion

This study was the first to demonstrate renal progression and mortality in a prospective cohort of mild-to-severe CKD patients over mean 55 months in China. At the end of study, a significant portion of patients remained alive and dialysis free. Patients with CKD in Western countries frequently die of CVD before developing ESRD.Citation3,Citation4 By contrast, this study showed that Chinese CKD patients were more likely to develop ESRD than to die. Reasons for this differential mortality were not clear but may be related to racial disparities and different CKD primary disease. Such as the more Chinese CKD patients with glomerulonephritis whereas more Western countries’ patients with diabetes. Another reason might result from establishing of our renal management clinic as we previously reported,Citation7 and Italian’ study also showed that CKD patients under regular nephrology care ESRD were more frequent developing ESRD than dying in patients at CKD stage 4 and 5.Citation8 After multidisciplinary care, Taiwan CKD patients also had a better survival rate and were more likely to initiate renal replacement therapy instead of mortality.Citation9 On the other hand, we must considerate it would overestimate the numbers of patients entering dialysis instead of death when we used hospital data compared with data of community population.

It should be admitted that this cohort was collected in a major medical center which may be not the main choices for the end-stage CKD in order to save money and escape the difficult register, then the mortality rate might be underestimated in our study, in China which is a densely populated country with low income and low medical insurance coverage. The most common cause for mortality was CVD, followed by infectious disease and cancer. There were emerging studies showed that there was an excess risk of cancer in patients in early CKD stages,Citation10 and after dialysis, cancer risk increased 10–80% according to studies, with relative risks significantly higher than in the general population.Citation10,Citation11

For occurrence rate of ESRD, four baseline characteristics were identified as risk factors by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis: diabetic nephropathy, lower hemoglobin level, lower eGFR (CKD stage 5 vs. CKD stage 1, 2, 3 and 4), and heavy proteinuria. Previous study showed that at elevated urine total protein was shown to be an independent risk factor for more rapid decline in kidney function.Citation12 Our results also showed that heavy proteinuria were independent risk factor for ESRD by multivariate Cox regression model.

In our cohort, chronic interstitial nephritis was the common cause of CKD stage 5 and might result from its neglect or difficulty in early detection. The main cause of chronic interstitial nephritis were Chinese herbs contained aristolochic acid (AA).Citation13 Chronic interstitial nephritis was the important cause of ESRD ranked after glomerulonephritis, hypertensive nephrosclerosis and diabetic nephropathy in China.Citation2

In our cohort, lower hemoglobin level at baseline is a risk factor for ESRD, but it was deleted after multivariable adjustment for other established risk factors. Very few studies had investigated the role of hemoglobin level as an independent risk factor for CKD progression and ESRD development.

Previous studiesCitation14 reported that the DM was risk factor of developing ESRD after adjusting for possible confounding variables, among participants with CKD progressing, presence of diabetes at baseline is a strong predictor for ESRD.Citation14,Citation15 Recently, diabetes is becoming a worldwide epidemic in both developed and developing countries, early detection and treatment of diabetes might prevent diabetes-related ESRD. Diabetes also is the risk factor for ESRD by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis in our cohort.

Any candidate factors were measured in this study, but they were not associated independently with renal progression in Multivariate Cox regress model (such as baseline diabetic nephropathy, hemoglobin level).

There are several limitations to this study that deserve mention. Our study did not include a large number of participants at highest risk for progression to death, as there is only 2.2% of the cohort progressed to death, our ability to contrast the relative impact of a predictor on the risk of mortality as compared to ESRD is limited, so we failed to conclude any significant variables as predictors for mortality in multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

This study showed CKD outcomes in a prospective cohort under nephrologic care for mean 55 months, and this study indicated that baseline diabetic nephropathy, lower hemoglobin level, lower baseline eGFR and heavy proteinuria were the risk of progression to ESRD. In this CKD cohort, patients were more likely to develop ESRD than death, and cardiovascular mortality was the leading cause of death, and then followed by infectious diseases and cancer in this population.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no competing interests. This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 81170706) (Grant No. 81341022) and Peking University Third Hospital Key Program Grant to AH Zhang (YZZ05-5-34). Major diseases of fund of Beijing Municipal Science & Technology commission (No. SCW 2009-08).

Acknowledgements

The Peking University Third Hospital Ethics Committee approved this study protocol.

References

- Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(1):1–12

- Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):815–822

- Dalrymple LS, Katz R, Kestenbaum B. Chronic kidney disease and the risk of end-stage renal disease versus death. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:379–385

- Landray MJ, Emberson JR, Blackwell L. Prediction of ESRD and death among people with CKD: the Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham (CRIB) prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(6):1082–1094

- Levey AS, Schmid CH, Zhang YP. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612

- Herzog CA, Asinger RW, Berger AK, et al. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. A clinical update from Kidney Disease: improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80(6):572–586.10

- Zhang AH, Zhong H, Tang W, et al. Establishing a renal management clinic in China: Initiative, challenges, and opportunities. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;l40(4):1053–1058

- Nicola LD, Chiodini P, Zoccali C. For the SIN-TABLE CKD Study Group: prognosis of ckd patients receiving outpatient nephrology care in Italy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2421–2428

- Chen YR, Yang Y, Wang SC, et al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for chronic kidney disease in Taiwan: a 3-year prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(3):671–682

- Stenge B. Chronic kidney disease and cancer: a troubling connection. J Nephrol. 2010;23(3):253–262

- Maisonneuve P, Agodoa L, Gellert R, et al. Cancer in patients on dialysis for end-stage renal disease: an international collaborative study. Lancet. 1999;354(9173):93–99

- Ardissino G, Testa S, Dacco V. Proteinuria as a predictor of disease progression in children with hypodysplastic nephropathy. Data from the Ital Kid Project. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:172–177

- Lai MN, Lai JN, Chen PC, et al. Risks of kidney failure associated with consumption of herbal products containing Mu Tong or Fangchi: a population-based case-control study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):507–518

- Iseki K. Predictors of diabetic end-stage renal disease in Japan. Nephrology (Carlton). 2005;10 Suppl:S2–S6

- Shurraw S, Hemmelgarn B, Lin M. Association between glycemic control and adverse outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(21):1920–1927