Abstract

Recurrence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a major therapeutic challenge in kidney transplantation (KT). Although intensive plasmapheresis and high-dose rituximab have been introduced to treat recurrent FSGS, the most effective dosage and regimen of rituximab have not been determined. Herein we reported the first case of successful treatment of recurrent FSGS with a low-dose rituximab. The patient showed marked proteinuria (3.5 g/d) and oliguria 2 d after KT. Two courses of plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin were applied to the patient, however, nephrotic range proteinuria persisted and creatinine level increased to 3.56 mg/dL. Five months post-transplant, the patient received injection with only one dose of rituximab 100 mg, without further plasmapheresis, which resulted in immediate reduction of serum creatinine and full remission of proteinuria during the following 18 months. This case suggested that recurrent FSGS, which frequently relapses after plasmapheresis, could be treated successfully with a low-dose rituximab even without plasmapheresis.

Introduction

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a major cause of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome.Citation1 In its primary or idiopathic form, FSGS is the cause of end-stage renal disease in 5% of adult patients.Citation2 Recurrence of FSGS has been reported in over 40% of kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) and proteinuria developed within 2–4 weeks after kidney transplantation.Citation3 As a main cause of allograft failure within 5 years in 10–30% of affected patients, refractory FSGS for conventional plasmapheresis/immunoglobulin therapy was a major therapeutic challenge.Citation4

After introduction of rituximab, various treatments using intensive plasmapheresis and high-dose rituximab have been studied in recurrent FSGS after kidney transplantation and the efficacy of rituximab in treatment of recurrent steroid-resistant FSGS has been reported.Citation5–11 Although these reports were not controlled, some patients with relapsed and refractory FSGS showed complete or partial remission with sustained response to rituximab therapy.

However, the mechanism of rituximab in the treatment of FSGS was obscure. In addition, the most effective dosage and regimen of rituximab have not been determined. Herein we reported the first case of successful treatment of recurrent FSGS with a low-dose rituximab. This case suggested that recurrent FSGS, which frequently relapses after plasmapheresis, could be treated successfully with low-dose rituximab therapy.

Case description

A 29-year-old male was admitted in order to undergo kidney transplantation from a deceased donor. The patient was diagnosed with minimal change disease at the age of 6, which was steroid dependent. As he had experienced frequent relapses under steroid therapy, cyclophosphamide and cyclosporine were attempted. However, multiple relapses still occurred and hemodialysis was started at the age of 22 with a presumptive diagnosis of FSGS. Seven years after hemodialysis, he was allocated to receive kidney transplantation from a deceased donor. The transplant contained three mismatches, including one DR mismatch and pre-transplant panel reactive antibodies were negative. The patient was in anuric state and plasmapheresis was not performed before surgery. The immunosuppressive regimen consisted of two doses of basiliximab at days 0 and 4, tacrolimus with a target trough level of 8–12 ng/mL, prednisolone, and mycophenolate. The allograft showed immediate diuresis of 2.0 L/d with serum creatinine level starting to decrease. However, 2 d after transplantation, the patient developed marked proteinuria (3.5 g/d) and oliguria. The clinical course and nephrotic range of proteinuria strongly suggested recurrent FSGS. The patient underwent nine sessions of plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin (total 600 mg/kg) for the treatment of recurrent primary disease. Although serum creatinine showed a decrease to normal values (1.1 mg/dL), nephrotic range proteinuria (4.7 g/d) persisted after treatment.

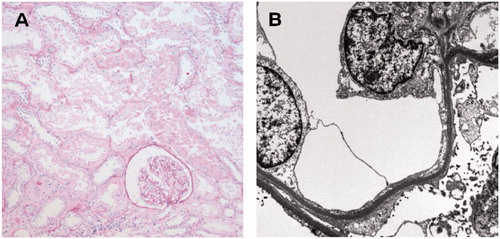

On day 54 after transplantation, the patient was readmitted for the treatment of increased serum creatinine to 1.98 mg/dL and proteinuria up to 7.5 g/d. Allograft biopsy showed recurrent FSGS with a foot process effacement of podocytes on electron microscopy and no evidence of cellular or humoral rejection was observed (). With steroid pulse therapy, another nine sessions of plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin (total 500 mg/kg) treatments were repeated and tacrolimus was changed to cyclosporine (5 mg/kg/d in two divided doses during fasting time) with a target trough level 150–300 ng/mL. After treatment, serum creatinine level returned to normal (1.0 mg/dL), however, proteinuria persisted above nephrotic range (6.2 g/d).

Figure 1. The first allograft biopsy on day 54 after transplantation showed no evidence of cellular or humoral rejection on light microscopy (A), however, revealed foot process effacement of podocytes on electron microscopy (B) which was compatible with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.

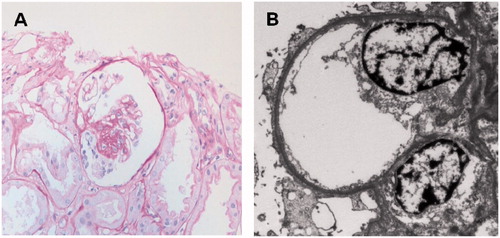

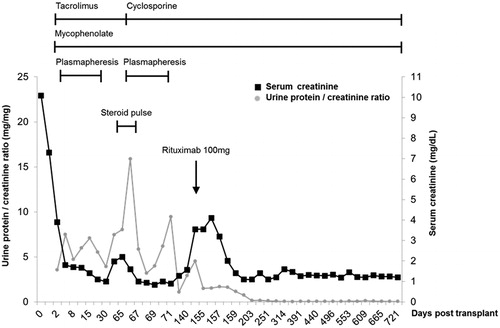

Three months later (on day 144 after transplantation), azotemia became aggravated, with serum creatinine of 3.56 mg/dL and proteinuria of 4.5 g/d. The second allograft biopsy showed definite focal segmental glomerular sclerosis with a foot process effacement of podocytes (). Only one dose of rituximab 100 mg was injected without further plasmapheresis. Azotemia showed rapid improvement with serum creatinine reaching 1.1 mg/dL on day 8 after injection of rituximab. Proteinuria also decreased consistently and showed complete remission (defined as spot urine protein/creatinine ratio <0.2) at 1.5 months after treatment. B cell count was 0% of peripheral blood when measured at 15 d after rituximab. The patient had maintained complete remission state of proteinuria with normal creatinine level (1.2 mg/dL) for 18 months ().

Figure 2. The second allograft biopsy on day 144 after transplantation showed a glomerulus with focal segmental sclerosis on light microscopy (A). Prominent foot process effacement of podocytes was also noted on electron microscopy (B).

Figure 3. Clinical course in terms of serum creatinine (mg/dL, black line) and urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (mg/g, gray line). After a single dose of rituximab 100 mg without further plasmapheresis, the patient maintained complete remission state of proteinuria with normal creatinine level for 18 months.

Discussion

Recurrent FSGS is a major problem in kidney transplantation for KTRs with FSGS. Plasmapheresis, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide have been the most frequently used therapeutic approaches. Clinical effectiveness of theses modalities is quite variable and allograft failure can occur in refractory FSGS patients.Citation4 In addition, the recurrence rate of FSGS increases up to 80% after the second kidney transplantation.Citation12

Pescovitz et al.Citation13 reported on the first case of recurrent FSGS in a KTR, which was treated with rituximab. The patient was diagnosed as recurrent FSGS and post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) after kidney transplantation. Six weekly doses of rituximab (375 mg/m2) were administered for the management of PTLD, resulting in concurrent ablation of proteinuria. After the report, various rituximab regimens consistently used a standard dose (375 mg/m2) or fixed dose (500–1000 mg) for treatment of recurrent FSGS and the number of injections varied from one to more than four times.Citation5–11 However, the dosage has been set for highly proliferative B cell diseases such as PTLD and lymphoma.Citation14 In KTRs, administration of a single dose of 35–150 mg/m2 (actual dose, 50–250 mg) rituximab resulted in complete elimination of B cells from the circulation within 3 d and B cell depletion was sustained for more than 1 year after injection.Citation15,Citation16 The current case also showed complete suppression of B cell count of peripheral blood after administration of a single low dose of rituximab. Therefore, in terms of B cell depletion, it was not supported that a higher dose of rituximab (>375 mg/m2) was more effective than a low dose of rituximab.

However, the role of B cells in pathogenesis of FSGS was controversial and the mechanism by which rituximab could induce remission in recurrent FSGS remained unknown. It was hypothesized that rituximab reduced a circulating permeability factor involved in the development of FSGS by direct depletion of CD20-positive B cells or indirect suppression of T cells or other cell types that interact with B cells.Citation17 Although soluble urokinase receptor was recently identified as a potential circulating factor involved in pathogenesis of FSGS,Citation18 more research is needed in order to establish the role of rituximab in decreasing the circulating factor and further reducing proteinuria in FSGS.

An off-target therapeutic effect of rituximab has recently been reported.Citation19 Rituximab showed cross-reactivity with sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase acid-like 3b (SMPDL-3b) protein, which was present in podocytes.Citation20 Treatment of recurrent FSGS with rituximab prevented disruption of the cytoskeleton and podocyte apoptosis by the inhibition of SMPDL-3b down-regulation. Results of this study suggested rituximab-medicated preservation of CD20-negative podocyte injury, rather than modulation of CD20-positive B cells, as a new pathogenic mechanism for recurrent FSGS. Further study of the dose- and frequency-dependent effects of rituximab on SMPDL-3b activity might reveal more effective rituximab regimens for use in the treatment of recurrent FSGS.

Recurrent FSGS might show drastic recovery from advanced state if pathogenic environment such as FSGS serum was removed.Citation21 This suggested podocyte injury before scar formation was a reversible and curable lesion. It could be postulated that rituximab provided favorable environment to recover podocyte injury. The mechanism of rituximab therapy in recurrent FSGS was not related to antibody depletion because serum immunoglobulins maintained the levels after rituximab therapy.Citation17 The effect of rituximab on FSGS treatment would be attributed to reduction of B-cell-mediated immune activation, removal of circulating factor, and other unrevealed pathogenic mechanisms. Although the exact mechanisms were not fully understood, it seems certain that, in some cases, rituximab could induce podocyte recovery and maintain the remission state for a substantial period.

The current case suggested that recurrent FSGS, which frequently relapsed after plasmapheresis, could be treated successfully with a low-dose rituximab, even without plasmapheresis. Treatment with low-dose rituximab might result in the improvement of recurrent FSGS, not only in a B cell-dependent manner but also by B cell-independent preservation of podocyte function. Low-dose rituximab therapy is applicable to patients with recurrent FSGS, especially those who are refractory to conventional treatment and worried about over-immunosuppression.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R & D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affair, Republic of Korea (HI10C2020).

References

- Gipson DS, Gibson K, Gipson PE, Watkins S, Moxey-Mims M. Therapeutic approach to FSGS in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;22(1):28–36

- Kitiyakara C, Eggers P, Kopp JB. Twenty-one-year trend in ESRD due to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(5):815–825

- Floege J. Recurrent glomerulonephritis following renal transplantation: an update. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1260–1265

- Newstead CG. Recurrent disease in renal transplants. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(90006):68vi–74vi

- Nakayama M, Kamei K, Nozu K, et al. Rituximab for refractory focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;23(3):481–485

- Yabu JM, Ho B, Scandling JD, Vincenti F. Rituximab failed to improve nephrotic syndrome in renal transplant patients with recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(1):222–227

- Rodríguez-Ferrero M, Ampuero J, Anaya F. Rituximab and chronic plasmapheresis therapy of nephrotic syndrome in renal transplantation patients with recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(6):2406–2408

- Strologo LD, Guzzo I, Laurenzi C, et al. Use of rituximab in focal glomerulosclerosis relapses after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88(3):417–420

- Bayrakci US, Baskin E, Sakalli H, Karakayali H, Haberal M. Rituximab for post-transplant recurrences of FSGS. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13(2):240–243

- Stewart ZA, Shetty R, Nair R, Reed AI, Brophy PD. Case report: successful treatment of recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with a novel rituximab regimen. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(10):3994–3996

- Audard V, Kamar N, Sahali D, et al. Rituximab therapy prevents focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis recurrence after a second renal transplantation. Transplant Int. 2012;25(5):e62–e66

- Meyer TN, Thaiss F, Stahl RA. Immunoadsorbtion and rituximab therapy in a second living-related kidney transplant patient with recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Transplant Int. 2007;20(12):1066–1071

- Pescovitz MD, Book BK, Sidner RA. Resolution of recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis proteinuria after rituximab treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(18):1961–1963

- Evens AM, Roy R, Sterrenberg D, Moll MZ, Chadburn A, Gordon LI. Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: diagnosis, prognosis, and current approaches to therapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12(6):383–394

- Toki D, Ishida H, Horita S, Setoguchi K, Yamaguchi Y, Tanabe K. Impact of low-dose rituximab on splenic B cells in ABO-incompatible renal transplant recipients. Transplant Int. 2009;22(4):447–454

- Genberg H, Hansson A, Wernerson A, Wennberg L, Tyden G. Pharmacodynamics of rituximab in kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84(12 Suppl):S33–S36

- Pescovitz MD. Rituximab, an anti-cd20 monoclonal antibody: history and mechanism of action. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(5 Pt 1):859–866

- Wei C, El Hindi S, Li J, et al. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17(8):952–960

- Perosa F, Favoino E, Caragnano MA, Dammacco F. Generation of biologically active linear and cyclic peptides has revealed a unique fine specificity of rituximab and its possible cross-reactivity with acid sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3b precursor. Blood. 2006;107(3):1070–1077

- Fornoni A, Sageshima J, Wei C, et al. Rituximab targets podocytes in recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(85):85ra46

- Gallon L, Leventhal J, Skaro A, Kanwar Y, Alvarado A. Resolution of recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis after retransplantation. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1648–1649