Abstract

Background: The etiology of minimal-change disease is not fully known, it is believed to be mediated by the immune system. Minimal-change disease also reported as having association with atopy. In this study, atopy history, the levels of serum IgE, and skin prick test in children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome were investigated. Methods: A group of 30 children (mean age 7.7 ± 2.2 years, 56.6% male) diagnosed with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome were included in the study. Serum immunoglobulin E levels and eosinophil counts were evaluated in children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome both in relapse and remission. Skin prick test was performed in remission. Results: Of the 30 children investigated, 11 (36.7%) had a history of atopy. The median serum total IgE levels in nephrotic children in relapse, with (445 IU/mL) and without atopy (310 IU/mL) were significantly higher than those in remission (respectively, 200 IU/mL, p = 0.021, and 42 IU/mL, p = 0.001). The skin prick tests for all the allergens were evaluated as negative in all the patients. Conclusion: It was thought that increased IgE may reflect the activation of immune mechanism following various stimuli rather than a direct association with atopy in children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome.

Introduction

The most frequent cause of steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome in children is minimal-change disease. Although the etiology of minimal change disease (MCD) is not fully known, it is believed to be mediated by the immune system.Citation1,Citation2 Minimal change disease is accepted as a T-cell disorder mediated by a circulating factor that creates podocyte dysfunction and massive proteinuria.Citation1,Citation3 Thirty percent of the patients with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS) have been shown to have allergic symptoms (e.g., asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and urticaria).Citation1–4 Nephrotic syndrome may be activated by inhaled allergens (pollens, dust and mold), food allergens or allergic reactions. Fanconi et al.Citation5 were the first in 1951 to show that children with nephrotic syndrome exhibited hypersensitivity in the skin test. In 1959, Hardwicke et al.Citation5 reported an association between pollen hypersensitivity and seasonal proteinuria. Indeed, in the last half-century, many studies have pointed to a strong association between nephrotic syndrome and atopy accompanied by increased levels of serum immunoglobulin E (IgE).Citation5 Although initial studies indicated high IgE levels in SSNS and in patients with frequent relapses,Citation6 later investigations reported different results.Citation7,Citation8 These different results derive from a lack of standardization in the study procedure.

CD80 receptor involving on podocyte was also found on Antigen Presenting Cells (APCs) and the role of this receptor in T cell activation was also reported. In minimal change disease, interleukin 13 (IL-13) secreted by the increased T-effector (Teff) cells, provided the transformation of IgE from IgM and the production of CD80 on podocytes. As a result of T regulatory (Treg) cell disfunction, pathological cytokines would be produced continuously together with the increase in serum IgE levels and proteinuria.Citation9 Fusion in food processes and proteinuria were observed by the induction of CD80 in rats.Citation10,Citation11 High levels of CD80 in urine and biopsy materials of the rats with MCD were reported in different experimental studies.Citation9,Citation12 The aim of this study was to evaluate the atopy of the children with SSNS.

Materials and methods

The research was performed between January 2006 and January 2010 with 30 nephrotic children (17 boys, 13 girls) of a mean age of 7.7 ± 2.2 (3.5–12) years. Patients who enter remission in response to corticosteroid treatment alone were referred to as having steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS).Citation1 Patients who displayed hypertension, persistent hematuria, kidney dysfunction, low complement levels and those resistant to or dependent upon steroids in the follow-up were excluded from the study. The cases were followed-up in the clinic as relapse or remission. Those with edema, severe proteinuria (3 consecutive days of >40 mg/m2/h or protein/creatinine >2 g/g and +3–4 protein on the urine strip) and hypoalbuminemia (<2.5 g/dL) were defined as having a “relapse” (onset). Those experiencing 3 d of protein release in the urine (<4 mg/m2/h and 0 or trace amount of protein or protein/creatinine <0.2 g/g on the urine strip) were defined as being in remission.Citation1 Infrequent relapse was defined as having one relapse in the first 6 months or between 1 and 3 relapses in any 12-month period after the initial response to nephrotic syndrome; frequent relapsing nephrotic syndrome (FRNS) was defined as having two or more relapses in the first 6 months or four or more relapses in any 12-month period after the initial response.Citation1 Initial treatment of childhood nephrotic syndrome was handled according to the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children (ISKDC), which suggests that treatment begin with prednisone at a dose of 2 mg/kg/d (maximum of 60 mg/d) in divided doses for 4 weeks, followed by tapering to 1.5 mg/kg/d for the next 4 weeks and then tapering down over 8 weeks.Citation13 Management of relapses generally includes reinstitution of oral daily steroids at a dose of 2 mg/kg/d divided bid (maximum of 60 mg/d) until the urine protein is trace or negative for 3–4 consecutive days, followed by a tapering of the steroids to 1.5 mg/kg as a single dose on alternate mornings, and gradual tapering down over approximately the following 6 weeks (∼0.25 mg/kg/dose/week until off). Among children with FRNS, the initial tapering to 1.5 mg/kg on alternate mornings was often continued for 2 weeks, and then the dose was very gradually tapered off over 5–6 months to try to reduce the frequency of the relapses.Citation13

Creatinine clearance was calculated according to the Schwartz formula.Citation14 Blood pressure measurements were taken with a suitable cuff applied to the right arm.

The patients and their first-degree relatives were questioned about asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis, recurring wheezing and urticaria.

Blood samples were taken from all of the children at the time of the nephrotic syndrome attack (before starting the steroid treatment) and at remission (4 weeks after the completion of the treatment). The total IgE measurement was taken using the immunoassay method with an IMX analyzer (Abbott Park, North Chicago, IL). The serum level of above 120 IU/mL was accepted as high. All of the patients were tested for eosinophil levels in the hemogram. Different persons administered the questionnaire and the skin test. The collected data were recorded in different places and were combined at the end of the study. Before the skin test, it was ensured that the patients had not undergone nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory, antihistaminic, decongestant or immunosuppressive treatment. None of the patients had infections and parasites. Skin prick tests were applied to all the patients during the remission period.

Prior to the start of the study, the informed consent of the families was obtained. This study was approved by the Ethics Board Committee of the University Hospital.

The skin prick test was conducted using a standard allergen extract panel (Stallergenes, France) and comprised histamine and saline respectively as positive and negative controls, 9 aeroallergens (tree mix, [maples, horse chestnuts, planes, false acacias and limes], weed mix [golden rod, dandelion, ox-eye-daisy and cocklebur], grass mix [cocksfoot, sweet vernal-grass, rye-grass, meadow grass and timothy], Dermatophagoides farinae [DF], Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus [DP], cockroaches (Blatella germanica), Alternaria alternata, cats, and feather mix [ducks, geese and hens]), and 6 common food allergens (cow’s milk, eggs, walnuts, hazelnuts, peanuts and wheat flour). Each test must be performed with separate needles. Appropriate materials were kept on hand in the light of anaphylactic risk.

No erythema, induration and pseudopod were evaluated as negative reaction. The erythema smaller than 21 mm was accepted as (+1), and bigger than 21 mm was accepted as (+2), induration without erythema and pseudopod was evaluated as (+3), and induration with erythema and pseudopod was evaluated as (+4) reaction.Citation15

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to examine the normal distribution of quantitative data. The independent sample t test was used to compare the data in normal distribution among the groups and the descriptive statistics were provided in the standard way with means. In the comparison of groups with data of non-normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney or the Wilcoxon test was used and the descriptive statistics were expressed in medians (25–75th percentiles). Chi-square analysis was used in the quantitative analysis of the data, with p < 0.05 being accepted as statistically significant.

Results

The patients' clinical and demographic data are given in . The male/female ratio was found to be 1.6. The mean age of nephrotic syndrome at diagnosis was 4.1 ± 2, and no difference was found between girls and boys according to the age of the diagnosis. Of the patients, 56.7% had infrequent relapses and 43.3% experienced frequent relapses. The average annual frequency for relapse was 2.3 ± 1years; the finding for those experiencing frequent relapse was 3.7 ± 0.4 attacks/year; that for those having infrequent relapses was 1.9 ± 0.7 (p < 0.001).

Table 1. Clinical data for children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome.

According to the history of allergy; 13.3% of patients had allergic rhinitis, 3.3% had asthma, 3.3% had food allergy. Mothers of children had all allergic rhinitis, urticaria, eczema 6.7%, 3.3%, 3.3%, respectively. The fathers of the children had all allergic rhinitis, asthma, 6.6%, 6.7%, respectively.

A history of atopy was found in 42.9% of patients and/or their families experiencing frequent relapse; this rate was 34.8% in those with infrequent relapse; and the difference was not found to be statistically significant (p > 0.05). Estimated creatinine clearance was 104 ± 7.6 mL/min (92–118 mL/min). Blood pressure measurements were found to be within the normal limits for age and gender. No significant difference was found between remission IgE (p = 0.207) and eosinophil (p = 0.190) levels when compared with the frequency of the attacks.

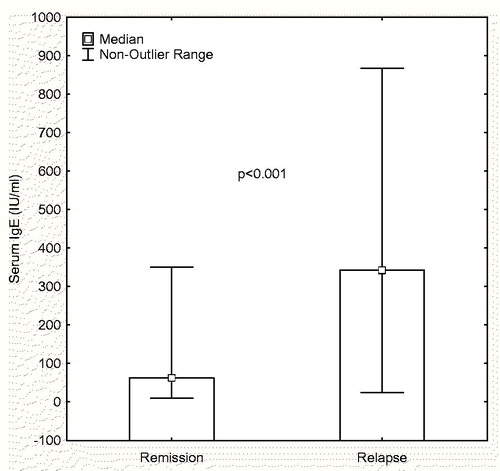

Increased serum attack IgE level was found in all of the children with frequent relapse and in 52.2% of those with infrequent relapse (p = 0.021). The high level of IgE during relapse median (25th–75th percentile) 342.5, (60.3–495) IU/mL decreased significantly in remission median (25th–75th percentile) 62.5, (34.8–210.8) IU/mL (p < 0.001) (). No difference was detected between remission and relapse eosinophil values (p > 0.05). As reported in the literature, 36.7% of the patients and/or their families had a history of atopy (11/30) ().

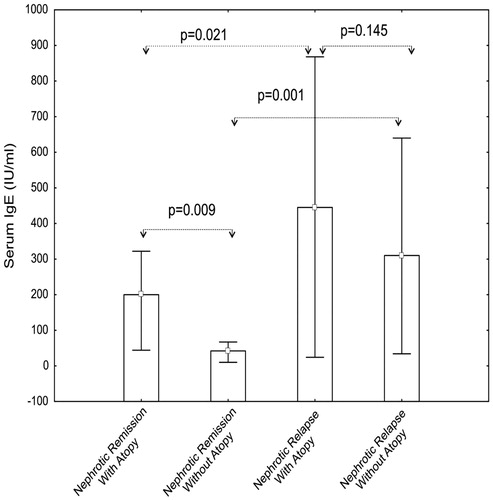

Of the 30 children with SSNS included in this study, 11 (36.7%) had a history of atopy. In order to determine whether the higher serum total IgE levels in children with SSNS in relapse were due to a higher incidence of atopy, patients were classified according to the presence or absence of a positive history of allergic conditions. The median serum total IgE levels in nephrotic children in relapse, with (445 IU/mL) and without atopy (310 IU/mL) were significantly higher than those in remission (respectively, 200 IU/mL, p = 0.021, and 42 IU/mL, p = 0.001) (). However, there was no significant difference between serum IgE levels in atopic and non-atopic patients in relapse (p = 0.145). In contrast, atopic children with SSNS in remission had a significantly higher median IgE level than non-atopic nephrotic children in remission (p = 0.009). No significant difference was seen between patients with and without a history of atopy in terms of the serum IgE levels in relapse (p = 0.145). There was no significant difference between patients with and without a history of atopy in terms of endurance in the skin prick test (p > 0.05).

Figure 2. Serum IgE levels in patients with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome with or without atopy.

As seen in (bold values), the history of frequent attacks was found to be significantly higher in those with high IgE values during attacks compared to those with normal values (36.8% vs. 0%, p = 0.021). Those with high IgE during attacks were found to respond to steroids in the second and third weeks, whereas those with normal values were seen to respond in the first week (p < 0.001). No significant difference was noticed between those with high and normal IgE values during attacks in terms of having a history of atopy either themselves and/or in their families (p = 0.979). The skin prick tests for all allergens were evaluated as negative in all of the patients. In the skin prick test, the patients with high and normal IgE values during attacks were not found to exhibit any significant difference in terms of endurance (p = 0.085).

Table 2. Comparison of children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome with high or normal IgE values during relapse.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of minimal-change disease is still unclear. As it has been stated in the past, the belief today too is that the immune system plays an important role in this condition.Citation5–9 In particular, there is strong evidence pointing to T-cell disorder mediated by a circulating factor that creates podocyte dysfunction and massive proteinuria.Citation2,Citation3 In many studies, increased incidence of allergic diseases and high serum IgE levels have been reported in SSNS.Citation2,Citation4–6,Citation9,Citation16–19 These findings support the existence of a dysfunction of the humoral immune response in the nephrotic syndrome.Citation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation18,Citation19 The term “atopy” is used to define IgE-mediated diseases. Atopic individuals are genetically sensitive toward widespread allergens and produce IgE antibodies; cytokines like IL-4 and IL-13 produced by T helper 2 (Th-2) cells.Citation20 IgE is basically produced by the action of two cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. In the absence of Treg cells suppression, the IL-4 and IL-13 secreted from the Teff cells result in an IgM→IgE switch inside the B cell. Increased IL-13 levels have been found in children with MCD in relapse when compared with remission and control group.Citation6,Citation15,Citation21–23 Although the IL-13 secreted from the T-cell was found to be directly associated with IgE, studies on IL-4 revealed different results.Citation18,Citation24–28 Podocytes express the CD80 receptor for IL-13 binding.Citation29,Citation30 The CD80 is a transmembrane protein that is also found in APC and plays a key role in the activation of T-cells. And also, in many studies showed that induction of CD80 by podocytes results in cell foot-process fusion and proteinuria.Citation10,Citation11,Citation29 In the present study, similar to other studies,Citation6–8 elevated IgE levels were found in nephrotic syndrome patients in relapse. But, as an assessment was not made for the cytokine levels and tissue biopsies, we were unable to make an interpretation.

Although the prevalence of atopy ranges were found between 10% and 50% in different series of nephrotic syndrome, the highest that has been reported is 30% to 40%.Citation1,Citation4,Citation9 The different rates related to patients' histories of atopy seem to be resulting from the use of different criteria in the defining of the condition. The present study found an atopic rate of 36% in children with SSNS, a finding that is consistent with the literature.

Due to the strong association between SSNS and atopy, the high IgE levels found in some studies have been thought to be a predictive factor for atopy in children with nephrotic syndrome.Citation4,Citation8 Most studies, in fact,Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation9,Citation18,Citation21,Citation22 have reported higher IgE levels in MCD patients compared to the control group. Fuke et al.Citation6 have shown that high IgE levels in nephrotic relapse, instead of playing a direct role in pathogenesis, are in fact a result of a dysfunction of the humoral immune system. Furthermore, it is also known that treatment with steroids has an impact on the IgE level and that hydrocortisone increases the production of IgE in mature B-cells in non-atopic individuals through the mediation of IL-4.Citation9 In the present study, in both atopic and non-atopic children with SSNS, IgE levels were found to be higher in relapse compared to remission, but no significant difference was found between those with and without a history of atopy in terms of their IgE levels. Moreover, atopic children with SSNS in remission were found to have higher IgE levels compared to non-atopic children. Many published studies report an association between high serum IgE levels with frequent relapse or a poor response to steroid treatment in children with nephrotic syndrome.Citation4,Citation5,Citation18 In our study, we showed that increased IgE level was associated with a late response to steroid treatment and with frequent relapses.

Nephrotic syndrome has been associated with allergies in many studies. Relapses have been reported in nephrotic patients after exposure to bee stings, pollen and other allergens, after vaccinations.Citation9,Citation31 Although increased IgE levels were found in MCD, this was not the case in other glomerular diseases.Citation9 It is known that the skin prick test has a 95% negative and a 50% positive predictive value in atopic patients.Citation32 In our study, we determined no positive reaction in the skin test in any of the children with SSNS. These results support the finding that atopy plays an indirect role in the pathogenesis of MCD, and that allergens and serum IgE seem to trigger the proteinuria.

In conclusion, allergic conditions are frequently found in children with MCD. This study showed that increased IgE levels in patients with SSNS in relapse and cases with high IgE experienced frequent relapses and showed a late response to treatment. We know that the immune system is the underlying reason for both SSNS and allergic diseases. We believe that, rather than having a direct association with atopy, the increase in serum IgE has more to do with various stimuli and is most likely mediated by immunological mechanisms. More research on a molecular level will contribute to revealing the association, which will in turn be beneficial in treating the condition.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Gbadegesin R, Smoyer WE. Nephrotic syndrome. In: Geary DF, Schaefer F, eds. Comprehensive Pediatric Nephrology, 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:205–218

- Shalhoub RJ. Pathogenesis of lipoid nephrosis: A disorder of T-cell function. Lancet. 1974;2:556–560

- Koyama A, Fujisaki M, Kobayashi M, Igarashi M, Narita M. A glomerular permeability factor produced by human T cell hybridomas. Kidney Int. 1991;40:453–460

- Meadow SR, Sarsfield JK, Scott DG, Rajah SM. Steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome and allergy: Immunological studies. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56:517–524

- Salsano ME, Graziano L, Luongo I, Pilla P, Giordano M, Lama G. Atopy in childhood idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:561–566

- Cheung W, Wei CL, Seah CC, Jordan SC, Yap HK. Atopy, serum IgE, and interleukin-13 in steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:627–632

- Rebien W, Müller-Wiefel DE, Wahn U, Schärer K. IgE mediated hypersensitivity in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Int J Pediatr Nephrol. 1981;2:23–28

- Lin CY, Lee BH, Lin CC, Chen WP. A study of the relationship between childhood nephrotic syndrome and allergic diseases. Chest. 1990;97:1408–1411

- Abdel-Hafez M, Shimada M, Lee PY, Johnson RJ, Garin EH. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome and atopy: Is there a common link? Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:945–953

- Reiser J, von Gersdorff G, Loos M, et al. Induction of B7-1 in podocytes is associated with nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1390–1397

- Reiser J, Mundel P. Danger signaling by glomerular podocytes defines a novel function of inducible B7-1 in the pathogenesis of nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2246–2248

- Garin EH, Diaz LN, Mu W, et al. Urinary CD80 excretion increases in idiopathic minimal-change disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:260–266

- Valentini RP, Smoyer WE. Nephrotic syndrome. In: Kher KK, Schnaper HW, Makker SP, eds. Clinical Pediatric Nephrology, 2nd ed. Oxon: Informa Healthcare; 2006:155–194

- Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM Jr, Spitzer A. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics. 1976;58:259–263

- Carr WW. Improvements in skin-testing technique. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2006; 27:100–103

- Wei CL, Cheung W, Heng CK, et al. Interleukin-13 genetic polymorphisms in Singapore Chinese children correlate with long-term outcome of minimal-change disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:728–734

- Florido JF, Díaz Pena JM, Belchi J, Estrada JL, García Ara MC, Ojeda JA. Nephrotic syndrome and respiratory allergy in childhood. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1992;2:136–140

- Yap HK, Yip WC, Lee BW, et al. The incidence of atopy in steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome: Clinical and immunological parameters. Ann Allergy. 1983;51:590–594

- Mishra OP, Ibrahim N, Usha, Das BK. Serum immunoglobulin E in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50:149–152

- Demoly P, Bousquet J, Romano A. In vivo Methods for the study of Allergy. In: Adkinson NF Jr, Broncher BS, eds. Middleton’s Allergy Principles & Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2009:1267–1279

- Tain YL, Chen TY, Yang KD. Implication of serum IgE in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:1211–1215

- Takei T, Koike M, Suzuki K, et al. The characteristics of relapse in adult-onset minimal-change nephrotic syndrome. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2007;11:214–217

- Kimata H, Fujimoto M, Furusho K. Involvement of interleukin (IL)-13, but not IL-4, in spontaneous IgE and IgG4 production in nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1497–1501

- Shimoyama H, Nakajima M, Naka H, et al. Up-regulation of interleukin-2 mRNA in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:1115–1121

- Neuhaus TJ, Wadhwa M, Callard R, Barratt TM. Increased IL-2, IL-4 and interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) in steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:475–479

- Adrogue HE, Borillo J, Torres L, et al. Coincident activation of Th2 T cells with onset of the disease and differential expression of GRO-gamma in peripheral blood leukocytes in minimal change disease. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:253–261

- Cho BS, Yoon SR, Jang JY, Pyun KH, Lee CE. Up-regulation of interleukin-4 and CD23/FcepsilonRII in minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:199–204

- Kaneko K, Tuchiya K, Fujinaga S, et al. Th1/Th2 balance in childhood idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Clin Nephrol. 2002;58:393–397

- Lai KW, Wei CL, Tan LK, et al. Overexpression of interleukin-13 induces minimal-change-like nephropathy in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1476–1485

- Parry RG, Gillespie KM, Mathieson PW. Effects of type 2 cytokines on glomerular epithelial cells. Exp Nephrol. 2001;9:275–283

- Kark RM, Pıranı Cl, Pollak VE, Muehrcke RC, Blaıney JD. The nephrotic syndrome in adults: A common disorder with many causes. Ann Intern Med. 1958;49:751–754

- Ballmer-Weber BK. Value of allergy tests for the diagnosis of food allergy. Dig Dis. 2014;32:84–88