Abstract

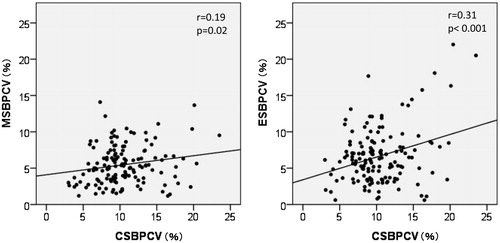

Although both clinic blood pressure (BP) variability and home BP variability are associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease, the relationship between both BP variabilities remain unclear. We evaluated the association between visit-to-visit variability of clinic BP (VVV) and day-by-day home BP variability (HBPV) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). We recruited 143 CKD patients in whom we performed HBP measurements every morning and evening over seven consecutive days. We obtained clinic BP data during 9.6 ± 1.0 consecutive visits within 24 months. The associations between the variables of VVV and HPBV were examined. The CV values of clinic systolic BP (CSBP) was significantly correlated with the mean values of morning systolic BP (MSBP) and those of evening systolic BP (ESBP) (r = 0.23, 0.20; p = 0.007, 0.02, respectively). The CV values of CSBP was significantly correlated with the CV values of MSBP and those of ESBP (r = 0.19, 0.31; p = 0.02, <0.001, respectively). On the multivariate regression analysis, the CV values of CSBP was significantly correlated with the CV values of MSBP and those of ESBP [standardized regression coefficient (β) = 0.19, 0.34; p = 0.03, <0.001, respectively]. In conclusion, VVV showed a weak but significant association with HBPV, especially the CV values of ESBP in CKD patients. Further studies are necessary to clarify whether these different BPV elements will be alternative marker of BPV.

Introduction

Recently, there has been accumulating evidence showing that blood pressure (BP) variability independent of the BP level has a prognostic significance of a risk of target organ damage or the development of cardiovascular diseases.Citation1–9 BP variability (BPV) includes different components of hours, days, weeks and months.Citation10,Citation11 BPV assessed by ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPV) is considered as a variable of short-term BPV, whereas day-by-day variability of BP assessed by home BP measurement (HBPV) and visit-to-visit variability of clinic BP (VVV) are considered as variables of medium-term or long-term BPV. At present, it remains unclear whether the causes, mechanisms and clinical significance are different between short-term BPV and medium-term or long-term BPV. In addition, scarce data regarding the relationship among these BPV elements are available. Some previous studies have assessed the correlation between ABPV and VVV.Citation2,Citation6,Citation11,Citation12 However, there are no data regarding the relationship between HBPV and VVV. It is not clear that these two BPV elements may be considered as an alternative marker of BPV each other.

Although it is not clear whether BPV is an additional target for hypertension management, several studies have shown the relationship between kidney or cardiovascular outcomes and BPV in CKD patients.Citation13–19 More studies are needed to clarify the clinical significance of BPV in CKD patients. To the best of our knowledge, there are as yet no studies regarding the relationship among the different BPV elements in CKD patients. The objective of this study is to examine the association between HBPV and VVV in CKD patients.

Methods

Patients

We enrolled 143 patients treated at our department between July 2012 and February 2013 who met the eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) CKD patients treated for at least 6 months at our clinic. CKD was diagnosed either presence of overt proteinuria or decreased kidney function according to the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)Citation20 <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. (ii) Their HBP measurements had already been obtained at regular intervals before participating in this study. We excluded those who started dialysis therapy or who had atrial fibrillation.

Of the 143 patients, 98 were men. The mean age at the time of HBP data collection was 70.4 ± 10.3 years (median 72, range: 28–98). The underlying renal diseases were as follows: chronic glomerulonephritis (n = 50), nephrosclerosis (n = 43), diabetic nephropathy (n = 41), polycystic kidney disease (n = 4), tubulointerstitial nephritis (n = 3) and reflux nephropathy (n = 2). These diseases were diagnosed on the basis of the medical history and renal biopsy findings.

The mean baseline serum creatinine level was 2.87 ± 1.99 mg/dL (median 2.47, range: 0.57–10.70) and the eGFR was 26.5 ± 18.7 mL/min/1.73 m2 (median 20.5, range: 4.2–81.5, CKD stages 2, 3, 4 and 5; n = 11, 33, 52 and 47, respectively), calculated from the following formula for Japanese patients: 194 × Cr−1.094 × age−0.287 (×0.739 for women).Citation21 The mean creatinine clearance rate was 34.1 ± 26.5 mL/min (median 25.6, range: 5.1–174.0, n = 123) and the urinary protein excretion rate was 1.24 ± 1.42 g/day (median 0.83, range: 0–9.1, n = 123). The mean hemoglobin level was 12.0 ± 1.6 g/dL (median 11.8, range: 8.0–17.3) and the serum uric acid level was 7.3 ± 1.5 mg/dL (median 7.4, range: 2.0–11.9). The mean body mass index was 23.8 ± 3.4 kg/m2 (median 23.4, range: 14.4–32.1). These data were obtained at the time of HBP data collection.

HBP measurements and data collection

HBP was measured according to the guidelines for HBP measurement of the Japanese Society of Hypertension (JSH).Citation22 BP was measured using oscillometric arm devices in a seated position after at least 1 min of rest. BP was measured in the morning before dosing, within 1 h of waking and in the evening just before bedtime. The value of a single measurement was recorded at each of these time points. The patients recorded 14 BP readings as described above for 7 days preceding their clinic visit. The following three variables of morning and evening BP values in the seven daily measurements were calculated for each patient: mean values, standard deviation (SD) values and coefficient of variation (CV) values. HBP data was collected between July and November in 138 patients. Only five patients recorded HBP data in winter (between December 2012 and February 2013).

Clinic BP measurements and data collection

Clinic BP was measured by a nurse using an electronic sphygmomanometer in a sitting position after at least 2 min of rest between 9 AM and 3 PM. The value of a single measurement was recorded. We obtained clinic BP data over a series of the preceding 6 to 10 consecutive visits including the visit when HBP data were collected. The numbers of visits were 9.6 ± 1.0 (numbers of visits: 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10; n = 6, 4, 5, 6 and 122, respectively). The observational period was 18.1 ± 5.4 months (≥6 to <12 months, ≥12 to <18 months, ≥18 to <24 months and 24 months; n = 21, 36, 44 and 42, respectively). The following three variables of BP values during the observational period were calculated for each patient: mean values, SD values and CV values.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tokyo Medical University (No. 2773) and all patients provided written informed consent to use their clinical data in this study.

Treatment during the observational period

We treated the patients according to the current guidelines of the JSH.Citation22 Antihypertensive drugs were selected according to the guidelines of the JSH.Citation23 The numbers of antihypertensive drugs taken by the subjects at the start of clinic BP data collection were as follows: 0 (n = 7), 1 (n = 32), 2 (n = 54), 3 (n = 35) and >4 (n = 15). The types of antihypertensive drugs taken by the subjects at baseline were as follows: angiotensin receptor blockers (n = 108), calcium channel blockers (n = 105), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (n = 30), α1 blockers (n = 30), αβ blockers (n = 16), β1 blockers (n = 11), α2 agonists (n = 3) and direct renin inhibitor (n = 3). Furosemide, thiazide and an aldosterone blocker were given to 29, 13 and 3 patients, respectively.

During the observational period, we changed several medication regimens to improve the BP control of the patients. The doses or numbers of antihypertensive drugs were increased in 40 patients during the study course, and the doses or numbers were decreased or the drugs were changed to another drug in the same class in 40 patients. The drugs were unchanged or continued not to be administered in 63 patients. The numbers of antihypertensive drugs taken by the subjects at the final clinic BP data collection (at the time of HBP data collection) were as follows: 0 (n = 6), 1 (n = 29), 2 (n = 52), 3 (n = 38) and >4 (n = 18). The classes of antihypertensive drugs were as follows: calcium channel blockers (n = 112), angiotensin receptor blockers (n = 111), α1 blockers (n = 35), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (n = 25), αβ blockers (n = 18), β1 blockers (n = 10), α2 agonists (n = 5) and direct renin inhibitor (n = 4). Furosemide, thiazide and an aldosterone blocker were given to 32, 18 and 4 patients, respectively. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents were given to 48 patients during the observation period.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD. p-Values of <0.05 were considered to represent statistically significant differences. Correlations between the CV values of clinic systolic BP (CSBP) and continuous variables were analyzed by the Pearson correlation coefficient. Correlations between those and categorical variables were analyzed by the Spearman’s correlation analysis. Multiple regression analysis was performed to identify the independent variables associated with the CV values of CSBP. To clarify the effect of home SBP in the morning and in the evening separately, the BP parameters of morning were included in Model 1 and those of evening are included in Model 2. Comparisons of the mean values between three or four groups were analyzed by the one-way analysis of variance. Multiple comparisons were performed by Bonferroni method. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Data of BP variables at baseline and during the follow-up period

shows the data of BP variables. Both the mean values of systolic BP and diastolic BP in the morning were significantly higher than those in the evening. The CV value of systolic BP in the evening was significantly higher than that in the morning. Both the mean values of systolic BP and diastolic BP in the morning were significantly higher than those of CSBP and diastolic BP, respectively. The SD values and CV values of all variables of clinic BP were significantly higher than those of BP in the morning and evening.

Table 1. BP parameters of the subjects.

Correlations between BPV and clinical variables

shows the univariate correlations between the CV values of CSBP and clinical variables including BP parameters.

Table 2. Univariate correlations between the coefficient variation of CSBP and clinical variables.

The CV values of CSBP were significantly correlated with the male gender, the number of antihypertensive drugs, urinary protein excretion, diabetic nephropathy and the changes of antihypertensive drugs during the observation period.

The CV values of CSBP were significantly correlated with the mean values of both morning systolic BP (MSBP) and evening systolic BP (ESBP), the CV values of both MSBP and ESBP. shows the correlations between the CV values of systolic BP in the morning and evening, and those of CSBP.

shows clinical variables and BP parameters of the groups according to the quartiles of the CV values of CSBP. The number of antihypertensive drugs and the mean values of systolic BP in the evening were significantly greater in the group of the highest quartile compared with in the group of the lowest quartile.

Table 3. Clinical variables and BP parameters of the groups according to the quartiles of the coefficient variation of CSBP.

No significant differences in the mean values and the CV values of systolic BP in the morning and evening, and those of CSBP were found among the groups of CKD stage 2 + 3, 4 and 5 (data not shown).

Multivariate regression analysis associated with BPV

shows the multivariate regression analysis of the CV values of CSBP as dependent variables.

Table 4. Multivariate regression analysis between the coefficient variation of CSBP and clinical variables (n = 123).

The CV values of CSBP was significantly correlated with the male gender and the CV values of MSBP in Model 1. Similarly, the CV values of CSBP was significantly correlated with the male gender and the CV values of ESBP in Model 2.

Because these models were analyzed in the patients who had the data of urinary protein excretion rate, the influence of the insufficiency of those data cannot be excluded. The multivariate regression analysis excluded urinary protein excretion rate as independent variable was performed. The CV values of CSBP was significantly correlated with the CV values of MSBP in Model 1 [standardized regression coefficient (β) = 0.20, p = 0.01, R2 = 0.23], and those was significantly correlated with the CV values of ESBP in Model 2 (β = 0.34, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.29).

In the group of patients without changes of antihypertensive drugs during the observational period (n = 65), the CV values of CSBP were significantly correlated with the male gender in Model 1 (β = 0.28, p = 0.048, R2 = 0.25). The CV values of CSBP were significantly correlated with the male gender and the CV values of ESBP in Model 2 (β = 0.31, 0.41; p = 0.02, 0.003, respectively; R2 = 0.34).

Discussion

We set out to clarify the association between HBPV and VVV in CKD patients. Although there were no significant differences in HBPV among the groups into the quartiles of VVV as shown in , significant associations were found between HBPV and VVV in the simple correlation and the multivariate regression analysis.

There are few data available regarding the relationship between different BPV elements. Several studies have shown a low correlation between ABPV and VVV.Citation2,Citation6,Citation11,Citation12 It is not clear whether the mechanisms are different among the different BPV elements. One recent study has shown significant associations between decreased vascular endothelial function and both ABPV and VVV in African Americans.Citation24 The etiology of both HBPV and VVV remain speculative. Increased arterial stiffness, decreased vascular endothelial function and increased sympathetic neural activity are the putative mechanisms of BPV.Citation8,Citation24–29 In addition, various physiological or behavioral factors, including waking and sleep cycles, mental and physical stress, temperature, and alcohol intake can affect both HBPV and VVV.Citation30–34

Previous studies have shown the factors affecting HBPV, including older age, female gender, high HBP and alcohol intake.Citation25,Citation30–32 The factors affecting VVV were almost similar to those affecting HBPV in several studies, including older age, female gender, high mean systolic clinic BP and history of myocardial infarction.Citation2,Citation3 In the current study, the male gender was associated with the CV values of CSBP, which is inconsistent with previous studies. Unfortunately, the numbers of female patients were about half of the male patients in the present study. The effect of gender might be inconclusive.

In the current study, the association between VVV and HBPV was greater in the evening than in the morning. The significance of this result is not clear. The current study and some previous studies have shown that HBPV is greater in the evening than in the morning.Citation35,Citation36 We speculate that BPV might increase more in the evening than in the morning because of the enhancing effect of various physiological or behavioral factors. Therefore, the correlation between VVV and HBPV might tend to appear greater in the evening.

In the current study, eGFR and CKD grade had no significant associations with VVV and HBPV. Previous studies have shown inconsistent results regarding the associations between eGFR and VVV.Citation8,Citation14,Citation16 Decreased GFR is associated with increased arterial stiffness and increased sympathetic neural activity.Citation37,Citation38 However, we speculate that the effect of decreased GFR itself on BP variabilities is weak, and the effect of antihypertensive treatment might attenuate the influence of GFR in the current study. It is necessary to evaluate the hypertensive subjects without CKD. Some previous studies have shown the association between albuminuria and VVV in CKD patients or patients with diabetic nephropathy.Citation15,Citation19 In the current study, the association between urinary protein excretion and VVV might be caused by the patients’ characteristics of underlying renal diseases, especially diabetic nephropathy.

In the current study, the change of antihypertensive drugs during the observational period was associated with VVV in the univariate correlations. Unfortunately, it is impossible to assess the specific effect of the changes of antihypertensive drugs on BPV in the current study. The timing of the changes or the classes of drugs was not uniform. It is difficult to evaluate the changes of VVV between before and after the changes of drugs. We speculate that the improvement of clinic and HBP might increase VVV in some patients whose antihypertensive drugs had been changed during the observational period of VVV. Several previous studies have shown the effects of the classes of antihypertensive drugs on BPV.Citation32,Citation39–42 Many CKD patients receive a combination of several antihypertensive drugs. In the current study, 73% of the patients (n = 105) received two or more antihypertensive drugs which consisted of a combination of a calcium channel blocker and a renin–angiotensin system inhibitor. Prospective study is necessary to clarify the effects of the change of the classes of antihypertensive drugs on BPV.

We examined HBPV at the final visit to our clinic. An important matter is when the data of HBP measurements should be obtained during the observational period of VVV. Although few data were available regarding HBPV reproducibility, our previous study has shown a significant correlation between the BPV of HBP measurements at baseline and those during the follow-up period in CKD patients.Citation36,Citation43 Therefore, some populations might have the characteristics of consistently high BPV.

It is not clear whether the information obtained by the measurements of the different BPV is considered as similar predictive role. However, the detection of patients with high BPV using HBPV instead of VVV or ABPV might be easy and useful for identifying patients of the risk of cardiovascular disease. More studies are necessary to clarify the relationship and clinical significance of the different BPV.

The present study has several limitations. First, the study cohort was small, possibly limiting the statistical power. Also, only patients who continued HBP measurements regularly were included in the study, thus bias in the selection of the study population cannot be completely ruled out. Second, the number of BP measurements both at home and in the clinic was only one on each occasion. Several studies have used one BP value on each occasion at home or in the clinic.Citation1,Citation40,Citation43 For a more definitive BP evaluation, it is recommendable to have 2 or more measurements of BP. Notably, the SD and CV values of HBP in the current study were almost similar to those of previous studies.Citation1,Citation4,Citation14,Citation35,Citation36,Citation43 The CV values of clinic BP in our study were also almost similar to those of previous studies.Citation6,Citation17,Citation18 Third, the study population had different numbers and classes of antihypertensive drugs as well as different underlying renal diseases. During follow-up, medication regimens were changed in about half of the patients. Thus, the possible effects of antihypertensive drugs on changes in VVV cannot be excluded. As it is essential to evaluate the relationship between HBPV and VVV in patients with hypertension without renal diseases, it is ideal to limit the enrolled patients to those without changes in antihypertensive drugs during the study. Fourth, we could not assess the influence of the season on BPV. HBP data was collected in summer and autumn in a majority of patients.

In conclusion, VVV of clinic BP and day-by-day HBPV showed a weak but significant association in CKD patients. There are some populations who have the characteristics of high BPV in both home and clinic. Further studies are necessary to clarify whether these different BPV elements will be alternative and complementary marker of BPV.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Associate Professor Edward F. Barroga, Senior Editor of the Department of International Medical Communications of Tokyo Medical University, for the editorial review of the article.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Metoki H, et al. Day-by-day variability of blood pressure and heart rate at home as a novel predictor of prognosis, the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2008;52:1045–1050

- Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, et al. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375:895–905

- Munter P, Shimbo D, Tonelli M, Reynolds K, Arnett DK, Oparil S. The relationship between visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure and all-cause mortality in the general population: Findings from NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Hypertension. 2011;57:160–166

- Matsui Y, Ishikawa J, Eguchi K, Shibasaki S, Shimada K, Kario K. Maximum value of home blood pressure: A novel indicator of target organ damage in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:1087–1093

- Johansson JK, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Jula AM. Prognostic value of the variability in home-measured blood pressure and heart rate: The Finn-home study. Hypertension. 2012;59:212–218

- Eguchi K, Hoshide S, Schwartz JE, Shimada K, Kario K. Visit-to-visit and ambulatory blood pressure variability as predictors of incident cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:962–968

- Leoncini G, Viazzi F, Storace G, Deferrari G, Pontremoli R. Blood pressure variability and multiple organ damage in primary hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:663–670

- Kawai T, Ohishi M, Ito N, et al. Alteration of vascular function is an important factor in the correlation between visit-to-visit blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1387–1395

- Stergiou GS, Ntineri A, Kollias A, Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Parati G. Blood pressure variability assessed by home measurements: A systematic review. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:565–572

- Rothwell PM. Does blood pressure variability modulate cardiovascular risk? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13:177–186

- Mancia G. Short- and long-term blood pressure variability, present and future. Hypertension. 2012;60:512–517

- Muntner P, Shimbo D, Diaz K, Newman J, Sloan RP, Scwartz JE. Low correlation between visit-to-visit variability and 24-h variability of blood pressure. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:940–946

- Kilpatrick ES, Rigby AS, Atkin SL. The role of blood pressure variability in the development of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2442–2447

- Ushigome E, Fukui M, Hamaguchi M, et al. The coefficient variation of home blood pressure is a novel factor associated with macroalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:1271–1275

- Kawai T, Ohishi M, Kamide K, et al. The impact of visit-to-visit variability in blood pressure on renal function. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:239–243

- Okada H, Fukui M, Inaba S, et al. Visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure is correlated with diabetic nephropathy and atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2012;220:155–159

- Mallamaci F, Minutolo R, Leonardis D, et al. Long-term visit-to-visit office blood pressure variability increases the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;84:381–389

- Yokota K, Fukuda M, Matsui Y, Hoshide S, Shimada K, Kario K. Impact of visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure on deterioration of renal function in patients with non-diabetic chronic kidney disease. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:151–157

- Okada H, Fukui M, Tanaka M, et al. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability is a novel risk factor for the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1908–1912

- Japanese Society of Nephrology. Clinical Practice Guidebook for Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease. Chapter 2. Definition and classification of CKD. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:196

- Japanese Society of Nephrology. Clinical Practice Guidebook for Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease. Chapter 9. Evaluation method for kidney function and urinary findings. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:209–211

- Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2009). Chapter 2. Measurement and clinical evaluation of blood pressure. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:11–23

- Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2009). Chapter 5. Treatment with antihypertensive drugs. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:33–39

- Diaz KM, Veerabhadrappa P, Kashem MA, et al. Relationship of visit-to-visit and ambulatory blood pressure variability to vascular function in African Americans. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:55–61

- Imai Y, Aihara A, Ohkubo T, et al. Factors that affect blood pressure variability, a community-based study in Ohasama, Japan. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:1281–1289

- Monaham KD. Effect of aging on baroreflex function in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integ Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R3–R12

- Grassi G. Sympathetic neural activity in hypertension and related diseases. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:1052–1060

- Shimbo D, Shea S, McClelland RL, et al. Associations of aortic distensibility and arterial elasticity with long-term visit-to-visit blood pressure variability: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:896–902

- Liu Z, Zhao Y, Lu F, Zhang H, Diao Y. Day-by-day variability in self-measured blood pressure at home: Effects on carotid artery atherosclerosis, brachial flow-mediated dilation, and endothelin-1 in normotensive and mild-moderate hypertensive individuals. Blood Press Monit. 2013;18:316–325

- Johansson JK, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Jula AM. Factors affecting the variability of home-measured blood pressure and heart rate: The Finn-home study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1836–1845

- Kato T, Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, et al. Factors associated with day-by-day variability of self-measured blood pressure at home: The Ohasama study. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:980–986

- Ishikura K, Obara T, Kato T, et al. Associations between day-by-day variability in blood pressure measured at home and antihypertensive drugs: The J-HOME-Morning study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2012;34:297–304

- Murakami S, Otsuka K, Kono T, Soyama A, Umeda T, Yamamoto N. Impact of outdoor temperature on prewaking morning surge and nocturnal decline in blood pressure in a Japanese population. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:70–73

- Kawano Y. Diurnal blood pressure variation and related behavioral factors. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:281–285

- Imai Y, Nishiyama A, Sekino M, et al. Characteristics of blood pressure measured at home in the morning and in the evening: The Ohasama study. J Hypertens. 1999;17:889–898

- Okada T, Nakao T, Matsumoto H, et al. Day-by-day variability of home blood pressure in patients with chronic kidney disease. Jpn J Nephrology. (in Japanese) 2008;50:588–596

- Kawamoto R, Kohara T, Tabara Y, et al. An association between decreased glomerular filtration rate and arterial stiffness. Intern Med. 2008;47:593–598

- Neumann J, Ligtenberg G, Klein IH, et al. Sympathetic hyperactivity in hypertensive chronic kidney disease patients is reduced during standard treatment. Hypertension. 2007;49:506–510

- Webb AJ, Fischer U, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM. Effects of antihypertensive-drug class on interindividual variation in blood pressure and risk of stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:906–915

- Smith TR, Drozda JP Jr., Vanslette JA, Hoeffken AS, Nicholson RA. Medication class effects on visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure measurements: Analysis of electronic health record data in the “real world”. J Clin Hypertens. 2013;15:655–662

- Matsui Y, O’Rourke MF, Hoshide S, Ishikawa J, Shimada K, Kario K. Combined effect of angiotensin II receptor blocker and either a calcium channel blocker or diuretic on day-by-day variability of home blood pressure: The Japan Combined Treatment With Olmesartan and a Calcium-Channel Blocker Versus Olmesartan and Diuretics Randomized Efficacy Study. Hypertension. 2012;590:1132–1138

- Levi-Marpillat N, Macquin-Mavier I, Tropeano AI, Parati G, Maison P. Antihypertensive drug classes have different effects on short-term blood pressure variability in essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:585–590

- Okada T, Matsumoto H, Nagaoka Y, Nakao T. Association of home blood pressure variability with progression of chronic kidney disease. Blood Press Monit. 2012;17:1–7