Abstract

Objectives: To explore the role of immunoadsorption (IA) for the treatment of idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) recurrence in the renal allograft, if applied in a personalized manner. Methods: We studied patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) due to idiopathic FSGS, transplanted between 2001 and 2010. Patients with FSGS recurrence were treated with daily sessions of IA for the first week, followed by an every other day scheme and then individualized tapering until discontinuation. Complete remission was defined as a reduction of 24-h proteinuria to ≤0.5 g/day and partial remission as a reduction of 24-h proteinuria to 50% or more from baseline. Results: Of the 18 renal transplant recipients with ESRD due to idiopathic FSGS, 12 (66.7%) experienced disease recurrence in a mean time of 0.75 months post-transplantation (KTx), with a mean proteinuria of 8.9 g/day at the time of recurrence. The mean recipient age was 30.8 years; the mean donor age was 47.4 years, while living related donors provided the allograft in seven cases. Four of the patients received therapy with rituximab in addition to IA. During a mean time of follow-up of 48.3 months, seven patients (58.3%) achieved complete remission, and five (41.7%) partial remission. At the end of follow-up, eight patients (66.7%) had functioning grafts, being in sustained remission, in contrast to four patients (33.3%), who ended up in ESRD because of FSGS recurrence. Conclusions: IA was shown efficacious in a small series of patients with recurrent FSGS in the graft. Renal function remained stable in eight of the 12 patients with FSGS recurrence.

Introduction

Recurrence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) in the transplanted kidney is usually a severe condition, occurring in ∼25% of the patients and being associated with poor graft survival.Citation1,Citation2 It is most frequently seen in the immediate phases after kidney transplantation (KTx), suggesting that podocyte injury is probably caused by a circulating factor, initially thought to be released by T cells.Citation3 A potential circulating factor, altering the glomerular permeability, has been identified as a 30–50 kd protein.Citation4,Citation5 The most recent, strongest, evidence for the presumed permeability factor relates to a soluble urokinase receptor, the soluble form of the urokinase type plasminogen (suPAR).Citation1,Citation6 Following this hypothesis, Zimmerman et al.Citation7 reported the first successful use of plasmapheresis in a patient with FSGS recurrence in 1985. Several investigators have reported results from the use of plasmapheresis in patients with FSGS recurrence in the allograft afterwards, with the majority showing that the treatment was effective in promoting partial or complete remission in a substantial proportion of them.Citation8 As an innovation of plasmapheresis, immunoadsorption (IA) columns have been developed to treat plasma, based on the ability of an immobilized antibody to selectively bind a circulating molecule and remove it from the plasma. The antibody is covalently bound to an inert and insoluble matrix, such as cellulose in a column of gel beads.Citation9

Considering the encouraging results from the use of plasmapheresis, and the advantageous features of IA, which allow more specific clearance of circulating immunoglobulins, without substitution of fresh frozen plasma or albumin,Citation10 we aimed to utilize this method in patients with FSGS recurrence in the graft.

Patients and methods

Study population and definitions

Between 2001 and 2010, 18 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), due to idiopathic FSGS, received a renal allograft at our institution, and they were subsequently monitored for disease recurrence. Disease recurrence was defined as a new onset of proteinuria, typically over 3 g/day, without evidence of acute rejection, extensive interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, transplant glomerulopathy or immunocomplex glomerular disease on allograft biopsy. During hospitalization for KTx, proteinuria was monitored daily, by 24-h urine collections. After discharge, clinical and laboratory monitoring was done twice weekly during the first month, once weekly during the second month, twice monthly during the third and fourth months and then once monthly to the end of the first year. At the outpatient unit visits proteinuria was also monitored by measurement of the 24-h protein excretion. A graft biopsy was performed at the time of recurrence suspicion, and the tissue was examined under light microscopy and immune-histochemistry. Complete remission was defined as the reduction of proteinuria to ≤500 mg/day, whereas partial remission was defined as the reduction of proteinuria to 50% or more of the baseline value, and ideally to less than 3.5 g/day. Sustained remission was defined as the prolonged over 12-month proteinuria remission. Twenty-four-hour proteinuria was checked once weekly during the first month, once monthly from then until month 6 and once every 3 months afterwards, until the end of follow-up period. Graft function was evaluated by the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), which was calculated by the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.Citation11

Preventive IA for FSGS recurrence

A protocol for the prevention of FSGS relapses was applied in all the KTx recipients with idiopathic FSGS. The pre-operation (prior to KTx) part was applied only in the case where there was a living donor, who had completed successfully the evaluation process. In such cases, IA sessions were initiated when the KTx was in schedule, and began a week before the operation. Preventive IA included three pre-operation sessions of IA, performed every other day for the week prior to KTx, followed by a second part with three sessions of IA every other day, for the 1st week post-KTx. Patients who were transplanted from deceased donors received only the post-KTx of IA part as prevention.

Therapeutic IA for FSGS recurrence

Once the FSGS recurrence was documented in a certain patient, a scheme of daily sessions of IA for 1 week was initiated. This was followed by gradual tapering to one IA session every other day for 2 weeks, and then two sessions per week for the two following weeks. Subsequently, the patients were assigned to one session per week for 2 weeks, and finally to one session per 10 days, the latter given twice. The above scheme was applied in patients who showed evident signs of clinical response, that is, decrease in proteinuria, increase in serum albumin and recover from the nephrotic state. Depending on the response, we followed an individualized protocol to taper the IA sessions in order to maintain the improvement, which had already been achieved. Individualization of the IA scheme was related to the intensity and total duration of the treatment. In this regard, if a patient did not show any improvement, in terms of proteinuria decrease, he would stay in the existing frequency of IA sessions, that is, the tapering process would slow down or even discontinue temporarily. This decision was made on the basis of new significant decrease of proteinuria (i.e., proteinuria reduction ≥25%).

All sessions of IA were performed using the Plasauto iQ device (Asahi, Tokyo, Japan), with a pair of cartridges for plasma separation and adsorption (Plasmaflo, Asahi, Tokyo, Japan and Immusorba PH-350, Asahi, Tokyo, Japan, respectively). The plasma volume processed was set at 1.5 times the individual patient plasma volume. Treatment with IA was administered through a central vein catheter and it was temporarily discontinued in case of serious infections, such as septicemia. Patients with a new flare after achievement of remission were treated in the same way. A small dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (i.e., 150 mg/kg) was administered after IA to replace some depleted antibodies. Four of the patients with recurrence (4/12) received rituximab in addition to IA using the following scheme: 375 mg/m2 BSA, which was given intravenously, once weekly for 4 weeks (patients 2, 4, 11 and 12 in ).

Immunosuppressive protocol for KTx

We administered induction treatment with basiliximab or daclizumab, in all the patients. They also received 500–1000 mg of methyl-prednisolone during surgery, followed by 20–40 mg/day orally, and a gradual steroid taper in the absence of rejection. All the patients in this study were preferably maintained with cyclosporine plus MPA formulations and methyl-prednisolone. We targeted C2 levels of 700–900 mg/dL for the 1st year post-transplant, tending to lower to 600–800 mg/dL afterwards.

This study was done in accordance with the “Declaration of Istanbul” regarding the studies related to clinical organ transplantation and thus all clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul as outlined in the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee with oversight authority for the protection of human research subjects.

Statistical methods

Descriptive data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and percentages of the total. Comparison between baseline and time-averaged values of the two groups was done using paired Student’s t-test, where appropriate; chi-square test was used for categorical data. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Study participants

Of 18 renal transplant recipients with a history of idiopathic FSGS, who were followed for a mean time of 48.3 months, 12 (66.7%) experienced recurrence of the disease. Detailed information regarding this patient group is provided in . Among the patients who did not experience disease recurrence (33.3%) (four males and two females), the mean recipient age at KTx was 31.2 years. In this patient group, the mean duration of hemodialysis (HD) prior to KTx was 11.2 months. The allograft came from living related donors in four cases (66.7%) and from deceased donors in two cases (33.3%). The mean human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch was 2.0 ± 1.0. In all the 18 patients this was the first KTx (). None of the patients had been diagnosed with the collapsing variant of FSGS in the native kidney biopsy.

Table 1. Characteristics of the kidney transplant recipients with idiopathic FSGS as primary disease.

Treatment of FSGS recurrence

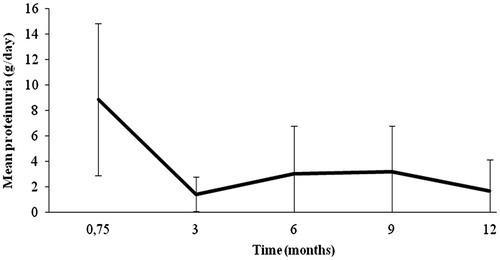

Among the 12 patients with FSGS recurrence, significant proteinuria was typically documented during the early postoperative period; the mean time to FSGS recurrence was 0.75 months () with a mean 24-h proteinuria of 8.9 g/day. These patients were treated intensively with IA but also in an individualized manner (). Remission of proteinuria was achieved in all the patients after a mean period of 2.6 months. As described earlier, 8/12 of the patients (44%), all of whom had received grafts from living related donors, had undergone a course of IA prior to KTx (preventive protocol), and 4/12 received additional therapy with rituximab for the FSGS recurrence (patients 2, 4, 11 and 12, ).

Table 2. Course of FSGS recurrence in the graft following treatment with IA.

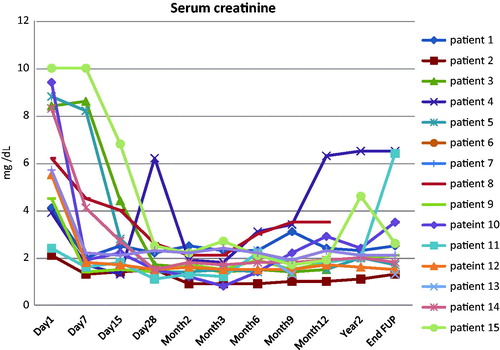

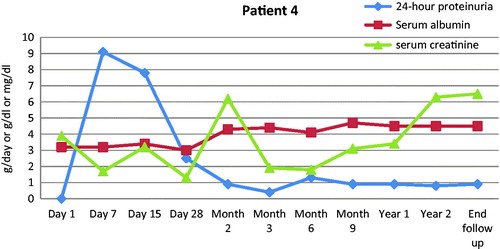

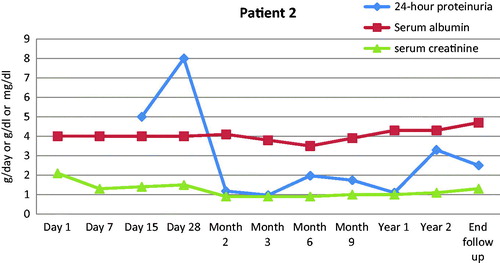

Mean 24-h proteinuria at remission was 1.4 ± 1.4 g/day. Seven patients (58.3%) achieved complete remission, whereas the remaining five (41.7%) achieved partial remission of proteinuria. Nine of the patients (75%) exhibited a new flare upon tapering of IA and thus, therapy with IA was reinstituted. The time course of 24-h proteinuria is displayed in . Three of these frequent relapsers (patients 2, 11 and 12) () were deemed IA-dependent; requiring over 100 IA sessions, to enter sustained remission (patient 2), or merely experienced delayed progression to ESRD (patients 11 and 12) (). At month 12, graft survival was 100% with satisfactory function (mean serum creatinine 2.0 ± 1.0 mg/dL) (). The mean follow-up time was 48.3 months and the mean number of IA sessions performed per patient was 83. At the end of follow-up, eight patients (66.7%) had functioning grafts, being in sustained remission, in contrast to four patients (33.3%), who ended up in ESRD because of FSGS recurrence. One of the latter patients (patient 8) () achieved complete remission after 11 sessions of IA, but he was lost from the follow-up visits and when he showed up again at month 16, he had ESRD.

Figure 1. Time course of mean 24-h proteinuria (g/day) in patients with FSGS recurrence in the graft following treatment with IA.

Figure 2. Serum creatinine (mg/dl) alterations from the time of FSGS recurrence to the end of follow-up.

As mentioned before, 8/18 (44%) renal transplant recipients with idiopathic FSGS in the native kidneys underwent prophylactic pre-transplant IA (). The recurrence rate in this group was 50% (4/8). In patients that did not receive preventive IA, the recurrence rate was higher (80%, 8/10). However, this result did not reach statistical significance and apparently the small numbers in both the groups do not permit certain considerations. No serious adverse events occurred during the IA procedure even in cases that needed long-term therapy.

Table 3. Rate of FSGS recurrence in the graft among kidney transplant recipients, who received or not IA pre-operatively.

Discussion

This study reports results from KTx recipients, who ended up in dialysis due to idiopathic FSGS and describes the rate of disease recurrence in the graft, and the effect of treatment with IA. During a follow-up time longer than 4 years it was shown that intensive and occasionally prolonged IA was effective in inducing sustained remission and preventing graft loss in 66.7% of the patients. We consider two characteristics as the most important in our series of patients: (i) the therapeutic IA protocol was initiated early and aggressively and (ii) it was gradually tapered or reinstituted following disease response and relapse individually. Prompt initiation of IA, in patients with established FSGS recurrence in the graft is pivotal, as the cycle of podocyte loss and unremitting proteinuria is associated with upregulation of transforming growth factor-β, and down regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor, thus mediating progressive glomerular scarring swiftly.Citation12 This is critical for KTx recipients, where nephron mass, which is provided with a single graft, is by designation reduced due to ischemia–reperfusion injury and immunosuppressive agent nephrotoxicity. This partially accounts for the accelerated loss of renal function in FSGS recurrence, compared to primary disease.Citation1 Reverse of the podocyte loss process is probably feasible only in the very early stage of disease recurrence, when the nephrin signaling or the enhanced angiotensin II, shear stress, or cell death gap junction signaling, has not touched many glomeruli.Citation1 If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, recurrent patients have already developed components of both primary and adaptive FSGS lesions, representing stages of the secondary form of the disease, which is by definition irretrievable.

Prophylactic IA was applied in all cases, still more intensively in those who were transplanted from a living donor. A protective role, basically for plasmapheresis before KTx, has been previously reported.Citation13,Citation14 Plasmapheresis and IA have mainly been used in the treatment of patients with documented recurrence. Ponticelli and GlassockCitation8 found that 70% of children (70%),Citation15–25 and 63% adults with recurrent FSGS, who received plasmapheresis, entered complete or partial remission.Citation8 The best results were obtained when aphaeresis was started early after KTx. In a study of 10 patients with FSGS recurrence, a 14-day course of high-dose cyclosporine and high-dose steroids associated with rigorous plasmapheresis for up to 9 months, lead to complete or partial remission in nine of them.Citation26

Systematic IA alone was shown sufficient to induce sustained remission in 2/3 of our patients. Since management of FSGS recurrence remains largely anecdotal due to the absence of multicentered controlled studies, most centers, use variable regimens, which include plasmapheresis in combination with pulse steroids, cyclophosphamide, high-dose cyclosporine or rituximab.Citation1,Citation27–30 The use of IA is superior to plasmapheresis, in terms of adverse events and the need for substitutive interventions afterwards. Plasmapheresis is a non-selective aphaeretic procedure, and preservation of several essential plasma components including albumin, immunoglobulins and clotting factors is not feasible.Citation9 Disadvantages of the selective aphaeretic procedures include high cost, complexity of procedures, limited availability and uncertainty of half life and stability of antibody-based IA columns.Citation31 The most recent technique in this type of aphaeretic modality is using immobilized antigens and synthetic epitopes applying secondary purification of plasma with columns containing immobilized antigen. These columns are designed to remove only the antibodies that are reactive with that specific antigen, that is, the pathogenic antibodies of specific antibody-mediated diseases. Such columns should leave untouched all other antibodies and other plasma constituents. This approach was pursued initially in dogs with anti-glomerular basement membrane diseaseCitation32,Citation33 and thus, the IA columns contained fixed preparations of glomerular basement membrane antigen. One potential problem is the possibility of antigen leaching out of the perfusion column, entering the patient and stimulating the immune system to produce more of the very antibody that is the cause of the disease. To overcome this problem, stable artificial epitopes have been built by synthetically combining peptide ligands covalently linked to Sepharose; these constructs mimic the antigenic sites with which specific pathogenic antibodies react, but they resist leaching when perfused with plasma.Citation9 IA columns constructed in this manner have been proved highly effective in the treatment of diseases such as idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, when used for secondary purification of separated plasma.Citation9 The optimal IA regimen, in terms of time of institution, frequency and total duration are not known. We rely on the clinical phenotype of the disease, plus a negative graft biopsy for any other pathology, to decide initiation therapy with of IA, since the typical histopathological lesions of FSGS may not be observed until 4–6 weeks after recurrence.Citation34 Likewise, most case series suggest that removal therapies are beneficial when used immediately after disease recurrence in the graft.Citation19,Citation22,Citation35–38 On the contrary, cessation of IA is decided if the patient shows no sign of improvement of proteinuria and/or declining renal function, which is associated with significant glomerulosclerosis on sequential graft biopsies.

The role of circulating factors in FSGS is supported by the rapidity of recurrence of after KTx. The fast recovery of allograft function after re-KTx into a patient without FSGS further supports this hypothesis.Citation2 Interestingly, Beaudreuil et al.Citation39 reported that the concentration of suPAR, although higher in the plasma of patients with recurrent FSGS, compared to HD patients, was shown similar before and after IA on protein A for the FSGS and HD samples. The suPAR concentration was very low in the eluates from protein A columns incubated with plasma from HD or FSGS patients, but still 85% of the patients with recurrent FSGS showed a decrease in immunoglobulin G and proteinuria.Citation39,Citation40 Notably, a study of 25 patients with recurrent FSGS showed that plasmapheresis with or without rituximab resulted in a significant reduction in proteinuria, decreased suPAR concentration and resolution or significant decrease in podocyte effacement.Citation40

Other interventions, which have been proposed for FSGS recurrence in the graft, consist of bilateral nephrectomy prior to KTx, intravenous cyclosporine or plasmapheresis followed by substitutive immunoglobulins in association with methyl-prednisolone pulses and cyclophosphamide.Citation38 Saleem et al. reported three children with severe, recurrent FSGS in their first allograft, treated with intravenous pulses of methyl-prednisolone, plasma exchange and cyclophosphamide on top of regular transplant immunosuppression with cyclosporine A and prednisolone.Citation21 Despite the good outcome in all the three cases, the authors underlined the substantial risks associated with heavy immunosuppression. Besides, the role of these extra immunosuppressants in the achievement of remission in each of these case series is difficult to be determined. As the total burden of immunosuppression in such patients is seriously increased by the time of FSGS recurrence in the graft, cumulative toxicity from any extra immunosuppression and its deleterious consequences should be considered cautiously.

We added rituximab in the treatment of four patients, while the remaining eight did not receive any supplementary immunosuppressant beyond the IA protocol. Two of these patients achieved remission and preserved renal function while the other two progressed to ESRD ( and ). The reason of rituximab addition was related to the fact that all the four patients had a history refractory disease in the native kidneys, despite utilization of all available therapies at that moment, and they had shown no sign of clinical response to IA by the time rituximab was instituted. Rituximab has been tried in patients with recurrent FSGS in the graft with variable success.Citation41–45 A recent study compared the relative risk of recurrence among patients, who were treated or not with this agent pre-transplant, but did not show any difference in the risk of FSGS recurrence post-transplant.Citation45

Figure 3. Time course of 24-h proteinuria (g/day), serum albumin and renal function for one of the four patients who received rituximab in addition to IA. He progressed to ESRD.

Figure 4. Time course of 24-h proteinuria (g/day), serum albumin (g/dl) and serum creatinine (mg/dl) for one of the four patients who received rituximab in addition to IA. Renal function remained stable while proteinuria went into remission.

It is in our strategy to maintain patients with a history idiopathic FSGS with cyclosporine, with the titration of the medication starting two weeks prior to the KTx. The anti-proteinuric effect of cyclosporine is attributed to suppression of T cells and inhibited production of cytokinesCitation46–48 but also to the inhibition of calcineurin mediated dephosphorylation of synaptopodin, a protein critical for stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton in kidney podocytes.Citation42 There are also reports confirming the reversing effect in proteinuria by giving oral or intravenous cyclosporine in high doses in children with recurrent FSGS.Citation38,Citation49,Citation50 Efforts to balance between nephrotoxicity and therapeutic effect are required. Shishido et al. in a recent report described the use of pulse methyl-prednisolone infusions for 6 months along with cyclosporine-based immunosuppression in pediatric patients with FSGS recurrence in the graft. Seven out of ten patients achieved remission of proteinuria while renal functionCitation28 remained stable. The usual triple immunosuppressive regimen, which is given to maintain KTx, is probably capable of inducing clinical remission in some patients by cessation the permeability factor production. Until then, the deleterious burden of the permeability factor should be removed speedily and aggressively. Yet, depending on the pathogenesis, the time for the adequate suppression of the “presumed” factor may be variable. FSGS is a lesion, not a disease, and thus different pathways maybe involved. If an “abnormal” clone of T cells has been secreting the circulating factor, then several parameters may play a role until clinical remission is achieved.Citation51

Limitations for this study pertain to the small number of patients included, which is an issue attributed to the low incidence of this disease. It is also reflected in the lack of data in the literature.Citation8 The lack of controls and the retrospective analysis of this data also preclude certain conclusions. It might be unethical to deprive a potentially beneficial therapy, especially considering that the two thirds of the patients responded well, and were able to preserve graft function in long term.

An aggressive scheme of IA, which was initiated instantly post-disease recurrence and was tapered gradually following the rate of disease response, was shown efficacious in the majority of the patients with FSGS recurrence in the graft. Cyclosporine was decisively part of the maintenance regimen, while the majority of the patients in this small series responded well, without any additional immunosuppressant. In cases of multiple relapses or refractory disease, a prolonged scheme of IA is probably justified, while the addition of rituximab may be beneficial for some patients.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- D'Agati VD, Kaskel FJ, Falk RJ. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(25):2398–2411

- Cravedi P, Kopp JB, Remuzzi G. Recent progress in the pathophysiology and treatment of FSGS recurrence. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(2):266–274

- Moriconi L, Lenti C, Puccini R, et al. Proteinuria in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Role of circulating factors and therapeutic approach. Ren Fail. 2001;23(3–4):533–541

- Zimmerman SW. Increased urinary protein excretion in the rat produced by serum from a patient with recurrent focal glomerular sclerosis after renal transplantation. Clin Nephrol. 1984;22(1):32–38

- Dantal J, Bigot E, Bogers W, et al. Effect of plasma protein adsorption on protein excretion in kidney-transplant recipients with recurrent nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(1):7–14

- Wei C, El Hindi S, Li J, et al. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17(8):952–960

- Zimmerman SW. Plasmapheresis and dipyridamole for recurrent focal glomerular sclerosis. Nephron. 1985;40(2):241–245

- Ponticelli C, Glassock RJ. Posttransplant recurrence of primary glomerulonephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(12):2363–2372

- Sanchez AP, Cunard R, Ward DM. The selective therapeutic apheresis procedures. J Clin Apher. 2013;28(1):20–29

- Belak M, Borberg H, Jimenez C, et al. Technical and clinical experience with protein A immunoadsorption columns. Transfus Sci. 1994;15:419–422

- Levey AS, Greene T, Beck GJ, et al. Dietary protein restriction and the progression of chronic renal disease: What have all of the results of the MDRD study shown? Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study group. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(11):2426–2439

- Ichikawa I, Ma J, Motojima M, et al. Podocyte damage damages podocytes: Autonomous vicious cycle that drives local spread of glomerular sclerosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14(3):205–210

- Ohta T, Kawaguchi H, Hattori M, et al. Effect of pre- and postoperative plasmapheresis on posttransplant recurrence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in children. Transplantation. 2001;71(5):628–633

- Gohh RY, Yango AF, Morrissey PE, et al. Preemptive plasmapheresis and recurrence of FSGS in high-risk renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(12):2907–2912

- Dall'Amico R, Ghiggeri G, Carraro M, et al. Prediction and treatment of recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis after renal transplantation in children. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34(6):1048–1055

- Laufer J, Ettenger RB, Ho WG, et al. Plasma exchange for recurrent nephrotic syndrome following renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1988;46(4):540–542

- Kawaguchi H, Hattori M, Ito K, et al. Recurrence of focal glomerulosclerosis of allografts in children: The efficacy of intensive plasma exchange therapy before and after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1994;26(1):7–8

- Mowry J, Marik J, Cohen A, et al. Treatment of recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with high-dose cyclosporine A and plasmapheresis. Transplant Proc. 1993;25(1 Pt 2):1345–1346

- Cochat P, Kassir A, Colon S, et al. Recurrent nephrotic syndrome after transplantation: Early treatment with plasmaphaeresis and cyclophosphamide. Pediatr Nephrol. 1993;7(1):50–54

- Cheong HI, Han HW, Park HW, et al. Early recurrent nephrotic syndrome after renal transplantation in children with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(1):78–81

- Saleem MA, Ramanan AV, Rees L. Recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in grafts treated with plasma exchange and increased immunosuppression. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(5):361–364

- Pradhan M, Petro J, Palmer J, et al. Early use of plasmapheresis for recurrent post-transplant FSGS. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(9):934–938

- Häffner K, Zimmerhackl LB, von Schnakenburg C, et al. Complete remission of post-transplant FSGS recurrence by long-term plasmapheresis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(7):994–997

- Garcia CD, Bittencourt VB, Tumelero A, et al. Plasmapheresis for recurrent posttransplant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(6):1904–1905

- Fencl F, Simková E, Vondrák K, et al. Recurrence of nephrotic proteinuria in children with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis after renal transplantation treated with plasmapheresis and immunoadsorption: Case reports. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(10):3488–3490

- Canaud G, Zuber J, Sberro R, et al. Intensive and prolonged treatment of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis recurrence in adult kidney transplant recipients: A pilot study. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(5):1081–1086

- Canaud G, Martinez F, Noël LH, et al. Therapeutic approach to focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis recurrence in kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Rev. 2010;24(3):121–128

- Shishido S, Satou H, Muramatsu M, et al. Combination of pulse methylprednisolone infusions with cyclosporine-based immunosuppression is safe and effective to treat recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis after pediatric kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(2):E143–E150

- Sethna C, Benchimol C, Hotchkiss H, et al. Treatment of recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: Effect of rituximab. J Transplant. 2011;2011:389542

- Stewart ZA, Shetty R, Nair R, et al. Case report: Successful treatment of recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with a novel rituximab regimen. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(10):3994–3996

- Balogun RA, Ogunniyi A, Sanford K, et al. Therapeutic apheresis in special populations. J Clin Apher. 2010;25(5):265–274

- Terman DS, Tavel T, Petty D, et al. Specific removal of antibody by extracorporeal circulation over antigen immobilized in collodion-charcoal. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977;28(1):180–188

- Terman DS, Buffaloe G, Mattioli C, et al. Extracorporeal immunoadsorption: Initial experience in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 1979;2(8147):824–827

- Shimizu A, Higo S, Fujita E, et al. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis after renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2011;25(Suppl 23):6–14

- Vinai M, Waber P, Seikaly MG. Recurrence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in renal allograft: An in-depth review. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14(3):314–325

- Dantal J, Baatard R, Hourmant M, et al. Recurrent nephrotic syndrome following renal transplantation in patients with focal glomerulosclerosis. A one-center study of plasma exchange effects. Transplantation. 1991;52(5):827–831

- Greenstein SM, Delrio M, Ong E, et al. Plasmapheresis treatment for recurrent focal sclerosis in pediatric renal allografts. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(12):1061–1065

- Cochat P, Schell M, Ranchin B, et al. Management of recurrent nephrotic syndrome after kidney transplantation in children. Clin Nephrol. 1996;46(1):17–20

- Beaudreuil S, Zhang X, Kriaa F, et al. Protein A immunoadsorption cannot significantly remove the soluble receptor of urokinase from sera of patients with recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(2):458–1456

- Alachkar N, Wei C, Arend LJ, et al. Podocyte effacement closely links to suPAR levels at time of posttransplantation focal segmental glomerulosclerosis occurrence and improves with therapy. Transplantation. 2013;96(7):649–656

- Cho JH, Lee JH, Park GY, et al. Successful treatment of recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with a low dose rituximab in a kidney transplant recipient. Ren Fail. 2014;36(4):623–626

- Hickson LJ, Gera M, Amer H, et al. Kidney transplantation for primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Outcomes and response to therapy for recurrence. Transplantation. 2009;87(8):1232–1239

- Meyer TN, Thaiss F, Stahl RA. Immunoadsorption and rituximab therapy in a second living-related kidney transplant patient with recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Transplant Int. 2007;20(12):1066–1071

- Kamar N, Faguer S, Esposito L, et al. Treatment of focal segmental glomerular sclerosis with rituximab: 2 case reports. Clin Nephrol. 2007;67(4):250–254

- Park HS, Hong Y, Sun IO, et al. Effects of pretransplant plasmapheresis and rituximab on recurrence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adult renal transplant recipients. Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29(4):482–488

- Tejani AT, Butt K, Trachtman H, et al. Cyclosporine A induced remission of relapsing nephrotic syndrome in children. Kidney Int. 1988;33(3):729–734

- Le Berre L, Godfrin Y, Perretto S, et al. The Buffalo/Mna rat, an animal model of FSGS recurrence after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(7–8):3338–3340

- Faul C, Donnelly M, Merscher-Gomez S, et al. The actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes is a direct target of the antiproteinuric effect of cyclosporine A. Nat Med. 2008;14(9):931–938

- Salomon R, Gagnadoux MF, Niaudet P. Intravenous cyclosporine therapy inrecurrent nephrotic syndrome after renal transplantation in children. Transplantation. 2003;75(6):810–814

- Raafat RH, Kalia A, Travis LB, et al. High-dose oral cyclosporin therapy for recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in children. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(1):50–56

- Shalhoub RJ. Pathogenesis of lipoid nephrosis: A disorder of T-cell function. Lancet. 1974;2(7880):556–560