Abstract

Background: Elderly patients are particularly susceptible to polypharmacy. The present study evaluated the renal effects of optimizing potentially nephrotoxic medications in an older population. Methods: Retrospective study of patients’ ≥60 years treated between January of 2013 and February of 2015 in a Nephrology Clinic. The renal effect of avoiding polypharmacy was studied. Results: Sixty-one patients were studied. Median age was 81 years (range 60–94). Twenty-five patients (41%) were male. NSAIDs alone were stopped in seven patients (11.4%), a dose reduction in antihypertensives was done in 11 patients (18%), one or more antihypertensives were discontinued in 20 patients (32.7%) and discontinuation and dose reduction of multiple medications was carried out in 23 patients (37.7%). The number of antihypertensives was reduced from a median of 3 (range of 0–8) at baseline to a median of 2 (range 0–7), p < 0.001 after intervention. After intervention, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) improved significantly, from a baseline of 32 ± 15.5 cc/min/1.73m2 to 39.5 ± 17 cc/min/1.73m2 at t1 (p < 0.001) and 44.5 ± 18.7 cc/min/1.73m2 at t2 (p < 0.001 vs. baseline). In a multivariate model, after adjusting for ACEIs/ARBs discontinuation/dose reduction, NSAIDs use and change in DBP, an increase in SBP at time 1 remained significantly associated with increments in GFR on follow-up (estimate = 0.20, p = 0.01). Conclusions: Avoidance of polypharmacy was associated with an improvement in renal function.

Introduction

Elderly patients are particularly susceptible to polypharmacy due to a combination of altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and the increased number of medications prescribed to them. It is estimated that 20% of the Medicare beneficiaries have five or more chronic conditions and 50% receive five or more medications.Citation1

These patients are more likely to be taking medications that are often redundant, ineffective or at higher than recommended doses. All these factors increase the risk of adverse side effects. Around one third of the patients older than 65 years receive potentially dangerous or inappropriate medications.Citation2

Some medications prescribed to these patients include antihypertensives and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs). These might be associated with hypotension, electrolyte imbalances and acute kidney injury.

Although under recognized, community acquired acute kidney injury (AKI) might be more common than hospital acquired AKI with similar poor long-term outcomes.Citation3

The present study evaluated the renal effects of optimizing potentially nephrotoxic medications in an older population. The hypothesis is that avoidance of polypharmacy is associated with improved renal function.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of the patients seen between January 2013 and February 2015. The study was approved by the Rice Memorial Hospital (Willmar, MN) Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged 60 years or older referred to the Nephrology Clinic because of chronic kidney disease and/or hypertension. These patients had follow-up with physical exams and laboratory tests.

As a standard practice, the nephrologists review the medication list, targeting excessive use (daily) of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and or antihypertensives. Some of these medications were discontinued or tapered down, based on each patient-specific situation. Indications for down-titration or discontinuation of medications include orthostatic hypotension, hypotension, weakness, dry mouth, daily use of NSAIDS, duplication of antihypertensive medications with the same mechanism of action and electrolyte imbalances attributed to medications.

Exclusion criteria

Patients on renal replacement therapy, history of organ transplant, vasculitis, biopsy proven glomerulonephritis or primary glomerular disease, autoimmune disease, hospitalization in the prior month, patients younger than 60 years, hospital acquired acute kidney injury and or renal replacement therapy in the prior month.

Variables collected

Age, gender, comorbidities, medication list, blood pressure (BP) before and after intervention, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) before and after intervention, proteinuria before and after intervention, mortality.

Estimation of glomerular filtration rate

GFR before and after the adjustment of the medication regimen was estimated by the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula (MDRD).Citation4

Estimation of proteinuria

Random urine albumin (albumin-to-creatinine ratio, expressed as mg/g) and total protein (protein-to-creatinine ratio, expressed as mg/g) were obtained after reviewing the medical records whenever available, before and after the intervention.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation if normally distributed and median [25% and 75% percentiles] or range if not. For parametric data, differences in means were compared by the paired t test. For highly skewed data, the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test was used.

Pearson`s or Spearman’s were used to test correlations. Differences in proportions were assessed by the Chi square or Fisher’s exact test (for parametric and non-parametric data respectively).

Multivariate linear and logistic models were used to study associations and adjust for confounding factors.

p Values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. All the analyses were performed using SOFA Statistics version 1.4.0 (Paton-Simpson & Associates Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) and JMP statistical software version 11.2.0 (SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC).

Results

The baseline patient characteristics are described in . Ninety-eight percent of the patients studied were Caucasian.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (N = 61).

Initially 61 patients were included in the study (time 0, t0), of these, 58 patients had complete follow-up at time 1 (t1) and 43 patients had complete follow-up at time 2 (t2), with a physical examination and electrolyte panel.

The median time to the first follow-up after the intervention (t1) was 29 days (range of 5–223). The median time to follow-up 2 (t2) was 99 days (range of 28–290).

At time 0, NSAIDs alone were stopped in 7 patients (11.4%), a dose reduction in antihypertensives was done in 11 patients (18%), one or more antihypertensives were discontinued in 20 patients (32.7%) and discontinuation and dose reduction of multiple medications was carried out in 23 patients (37.7%).

ACEIs/ARBs were discontinued or their dose reduced in 22 patients (36%). The number of antihypertensives was reduced from a median of 3 (range of 0–8) at baseline to a median of 2 (range 0–7), p < 0.001 after intervention.

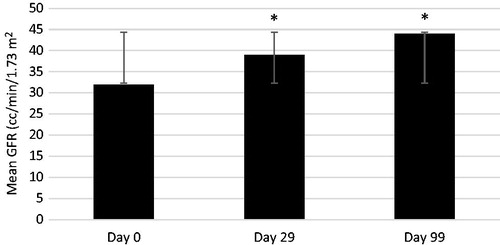

After intervention, the GFR improved significantly, from a baseline of 32 ± 15.5 cc/min/1.73m2 to 39.5 ± 17 cc/min/1.73m2 at t1 (p < 0.001) and 44.5 ± 18.7 cc/min/1.73m2 at t2 (p < 0.001 vs. baseline) ().

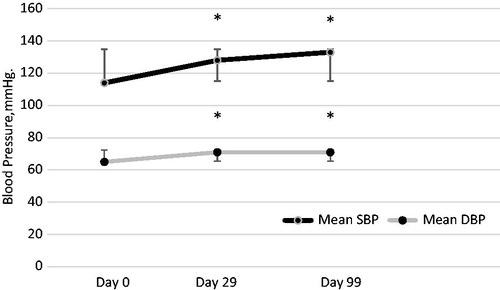

The systolic blood pressure increased from 114.4 ± 14 mmHg at baseline to 127.8 ± 14.3 mmHg at t1 (p < 0.001) and 132.9 ± 16.6 mmHg at t2 (p < 0.001). The same applies to the diastolic blood pressure; 64.5 ± 9.8 mmHg at baseline versus 70.9 ± 10.1 mmHg at t1 (p = 0.001) and 70.6 ± 8.8 mmHg at t2 (<0.001) ().

Systolic blood pressure values at t2 were significantly higher when comparing to values at t1 (p = 0.01). No significant differences were noted between diastolic blood pressures at t1 and t2.

In the entire cohort, the glomerular filtration rate at t1 improved or remained stable in 53 patients, and got worse in 5 patients. There was no significant difference in these patients in baseline characteristics, comorbidities, blood pressure values or baseline renal function (not shown).

At t2, renal function remained stable or improved comparing to baseline in 37 of 43 patients (86%).

In the entire cohort, there was no statistically significant difference in proteinuria after intervention: 66 mg/g [3.9, 192] at baseline versus 77.3 mg/g [2.6, 167] on follow-up, p = 0.35.

Among those in whom the ACEIS/ARBs were discontinued or their dose reduced, the median proteinuria at baseline was 100 mg/g [7.1, 449], on follow-up it was 78 mg/g [0, 300] p = 0.94.

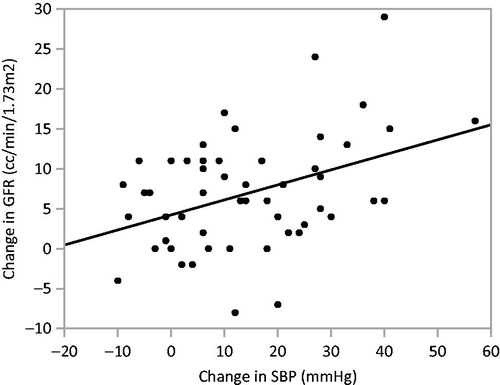

An increment in systolic blood pressure at t1 was associated with increased GFR at t1 (R2 = 0.16, p = 0.003), and time 2 (R2 = 0.13, p = 0.003, not shown).

Figure 3. Association between systolic blood pressure and renal function. Note: R2 = 0.16, p = 0.003. SBP = systolic blood pressure; GFR = glomerular filtration rate.

In a multivariate model, after adjusting for ACEIs/ARBs discontinuation/dose reduction (since one could argue this could be a hemodynamic effect), NSAIDs use and change in DBP, an increase in SBP at time 1 remained significantly associated with increments in GFR at t1 (estimate = 0.20, p = 0.01).

There were five deaths, but a significant conclusion cannot be reached about this. Three patients died from GI bleed, one from sepsis in the setting of colon cancer and one from end stage liver disease. This further suggests the extensive number of comorbidities in this population.

Discussion

Among patients with hypertension in the United States, more than half are ≥60 years. These patients are more likely to receive care from several healthcare providers, each of whom may prescribe a different medication.Citation5

Avoidance of polypharmacy is of paramount importance in the elderly, as the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of medications are altered. This is further exacerbated in cases of decreased renal or hepatic function.Citation6–9

Furthermore, the estimated incidence of drug interactions rises from 6% in patients taking two medications a day to 50% in patients taking five a day.Citation10

Polypharmacy is a risk factor for poor outcomes. For instance, a study of approximately 27,600 elderly Medicare patients documented more than 1500 adverse effects in a single year.Citation11

The American Geriatric Society Beers criteria highlight some of the potentially dangerous medications for older patients. This list includes a wide variety of medications, including antihypertensives and analgesics.Citation12

Common adverse reactions associated with antihypertensive use in older adults include electrolyte imbalances, acute kidney injury, and orthostatic hypotension.Citation13

Renal side effects of NSAIDs include hypertension, fluid retention and acute kidney injury. The incidence and the severity increase in patients with risk factors such as diabetes, heart failure, renal dysfunction and older age.Citation14

The Eighth Joint National Committee recommends starting treating blood pressure values ≥150/90 in patients older than 60 years. The target for patients younger than 60 and/or with CKD is 140/90 or below.Citation15

In the guidelines provided by the American Society of Hypertension (ASH) and the International Society of Hypertension the treatment threshold of ≥150/90 only applies to patients 80 years or older.Citation16

In the older population, a landmark study was HYVET. This study focused on people older than 80 years and showed benefits in treating hypertension in this population. Nonetheless, the baseline blood pressure was in the 170 s/90 s and the target blood pressure after intervention was <150/80 mmHg. Comparing to placebo, active treatment was associated with a 30% reduction in the rate of fatal or nonfatal stroke, a 39% reduction in the rate of death from stroke, a 21% reduction in the rate of death from any cause, a 23% reduction in the rate of death from cardiovascular causes and a 64% reduction in the rate of heart failure.Citation17

The present study focused on the changes in renal function associated with proper tailoring of potentially dangerous or superfluous medications in a population at risk. The intervention improved renal function by more than 30% (based on estimated glomerular filtration rate changes), a change that persisted over time (independent of just stopping or reducing the dose of the ACEIs or ARBs or NSAIDs). The blood pressure readings also increased, but still well within the normal acceptable limits.

One hypothesis is that these patients might have been suffering from hypotensive episodes and undiagnosed episodes of acute kidney injury, caused by polypharmacy. Older patients, especially those with long history of hypertension and chronic kidney have a decreased renal auto regulatory capacity.

By optimizing the blood pressure, it is reasonable to believe the renal perfusion improved. One concern in this regards would be primary renal vasodilatation, with a greater reduction in afferent relative to efferent arteriolar resistance resulting in increased intraglomerular pressure and glomerular hyperfiltration, with subsequent proteinuria, which portends a poor renal prognosis. In this study, there was no evidence of worsening proteinuria after the intervention, which is reassuring.

This result adds to a growing body of evidence that cautions against aggressive blood pressure control in older patients. Hypotensive episodes increase the risk of syncope, worsening renal disease and falls. Excessive use of antihypertensive medications in older patients is associated with serious fall injuries, including hip and other major fractures, traumatic brain injuries, and joint dislocations, especially in patients receiving more intensive therapy. The effect is even worse in those who already had previous fall injuries.Citation18

Careful management of blood pressure is warranted in chronic kidney disease patients. A recent study of older patients with chronic kidney disease showed that patients with systolic blood pressures of 130 to 159 mm Hg combined with diastolic blood pressures of 70 to 89 mm Hg had the lowest adjusted mortality rates, comparing to those with higher or lower BP readings. This is a different group than the younger patients with proteinuria, in which more aggressive blood pressure control is needed.Citation19

Similarly, Simm et al., in a study of almost 400,000 hypertensive patients showed higher mortality rates for blood pressures higher and lower than 130–139 mmHg (systolic) and 60–79 mmHg (diastolic). In their study, patients older than 70 years had the lowest risk at a value of around 140/70 mmHg.Citation20

In this study, some of the patients could have been suffering from acute kidney injury (AKI), although none of the cases was detected until the nephrology evaluation. These patients were ambulatory, believed to be in their usual state of health, which can be misleading for many practitioners. Acute kidney injury is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. An increase in SCr ≥0.5 mg/dL is associated with a 6.5-fold increase in the odds of death, an increase in hospitalization days, and higher hospital costs.Citation21

Acute kidney injury not only develops in the hospital setting. Community acquired acute kidney injury is associated with a mortality rate at 3 months of 16.5%. These patients have an increased risk for progressive CKD and mortality. This is a condition under recognized by most primary care providers. Factors associated with community acquired AKI are the use of potentially nephrotoxic medications (i.e. NSAIDS, antibiotics) and the inadequate titration of blood pressure medications.Citation22

It is remarkable to note that in this study, the GFR improvement persisted over time. This is an important finding, as lower GFR is independently associated with hospitalizations, cardiovascular events, end stage renal disease and death. Of course, not all the patients might benefit from this simple intervention (avoiding polypharmacy), but a good number of them do. One could postulate that this should be the first step when evaluating a patient who otherwise appears stable, but suffering from poor renal function. One cannot negate the beneficial effects of beta blockers, diuretics and ACEIs/ARBS in treating hypertension and cardiovascular disease. But in the very elderly population, maybe a more careful dosage and evaluation of their effects is necessary to avoid complications.Citation23

Strengths of this study include the longitudinal follow-up, and the study of a contemporary patient population. The major limitations of this study include the small number of patients, the lack of significant minorities enrolled and the lack of a control group or a randomized design. Also, the patient population is from rural Minnesota, which makes it difficult to apply to the inner city setting.

In conclusion, drug management in the elderly requires careful individualization, adequate follow-up and frequent evaluation and titration of the therapy. Avoidance of polypharmacy was associated with an improvement in renal function.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST Jr, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2870–2874

- Simon SR, Chan KA, Soumerai SB, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use by elderly persons in U.S. Health Maintenance Organizations, 2000–2001. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):227–232

- Der Mesropian PJ, Kalamaras JS, Eisele G, Phelps KR, Asif A, Mathew RO. Long-term outcomes of community-acquired versus hospital-acquired acute kidney injury: A retrospective analysis. Clin Nephrol. 2014;81(3):174–184

- Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:247–254

- Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(133):1–8

- Lim WK, Woodward MC. Improving medication outcomes in older people. Aust J Hosp Pharm. 1999;29(2):103–107

- Willlams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917–1924

- Richardson K, Bennett K, Kenny RA. Polypharmacy including falls risk-increasing medications and subsequent falls in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):90–96

- Beers MH, ed. Section 1: Basics of geriatric care. Clinical pharmacology. In: The Merck Manual of Geriatrics. 3rd ed., Chapter 6. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2005:54–74

- Corcoran ME. Polypharmacy in the older patient with cancer. Cancer Control. 1997;4(5):419–428

- Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA. 2003;289(9):1107–1116

- American Geriatrics Society. 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–631

- Marcum ZA, Fried LF. Aging and antihypertensive medication-related complications in the chronic kidney disease patient. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20(5):449–456

- Harirforoosh S, Jamali F. Renal adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8(6):669–681

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–520

- Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: A statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16(1):14–26

- Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al.; HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887–1898

- Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DS, et al. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):588–595

- Kovesdy CP, Bleyer AJ, Molnar MZ, et al. Blood pressure and mortality in U.S. veterans with chronic kidney disease: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(4):233–242

- Simm JJ, Shi J, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Jacobsen SJ. Impact of achieved blood pressures on mortality risk and end-stage renal disease among a large, diverse hypertension population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(6):588–597

- Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365–3370

- Talabani B, Zouwail S, Pyart RD, Meran S, Riley SG, Phillips AO. Epidemiology and outcome of community-acquired acute kidney injury. Nephrology (Carlton). 2014;19(5):282–287

- Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305