Abstract

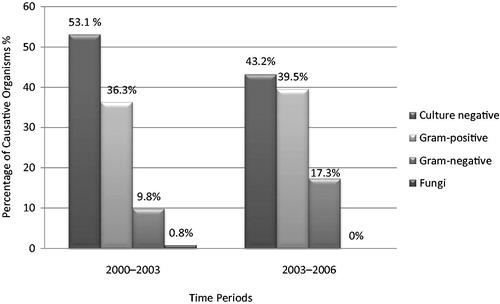

Aim: Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (PD) has become a treatment modality for end stage renal disease with a peak of its use in 1990s. The aim of this study was to examine the peritonitis rates, causative organisms and the risk factors of peritonitis in a large group of patients in our center. Methods: The study was conducted in the Nephrology Department of a University Hospital in Turkey. Patients in the PD programme between January 2000 and January 2006 were included. Cohort-specific and subject specific peritonitis incidence, and peritonitis-free survival were calculated. Causative organisms and risk factors were evaluated. Results: Totally 620 episodes of peritonitis occurred in 440 patients over the six years period. Peritonitis rates showed a decreasing trend through the years (0.79 episodes/patient-year 2000–2003 and 0.46 episodes/patient-year 2003–2006). Cohort-specific peritonitis incidence was 0.62 episodes/patient-years and median subject-specific peritonitis incidence was 0.44 episodes/patient-years. The median peritonitis-free survival was 15.25 months (%95 CI, 9.45–21.06 months). The proportion of gram-negative organisms has increased from 9.8% to 17.3%. There was a significant difference in the percentage of culture negative peritonitis between the first three and the last three years (53.1% vs. 43.2%, respectively). Peritonitis incidence was higher in patients who had been transferred from HD, who had catheter related infection and who had HCV infection without cirrhosis. Conclusions: Our study showed significant trends in the peritonitis rates, causative organisms and antibiotic resistance. Prior HD therapy, catheter related infections and HCV infection were found to be risk factors for peritonitis.

Introduction

Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (PD) was introduced in 1976 and afterwards it has become a treatment modality for end stage renal disease (ESRD). From 1980 to 1995 there has been an increase in the use of PD with a peak at 1990s.Citation1 However, after articles reporting poor outcomes for PD patients than hemodialysis (HD) patients, there was a decrease in PD patients from 1995 until 2010 in the United States (US),Citation2 but there was not a significant change in the developing countries. In 2010, proportion of patients initiating PD has started to increase in the US, which was attributed to the new payment system which has incentives for PD and developing automated PDCitation3 systems. In Turkey, the number of prevalent PD patients increased five-fold from 1124 to 5774 between 1996 and 2008, whereas HD patients increased approximately six-fold (40,264) and kidney transplant patients 2.5-fold (7824).Citation4

Peritonitis remains the major complication of PD that leads to hospitalization, transfer to HD, membrane failure and mortality.Citation5–8 Peritonitis rates vary widely according to the study design, populations’ age, race, educational background and environment. In the early 1980s the peritonitis rate was as high as 6.3 episodes/patient-year.Citation9 According to the CAPD Registry of the National Institutes of Health’s report in 1986 the rate decreased to 1.07–1.47 episodes/patient-year and in 2004 to 0.4 episodes/patient-year.Citation6,Citation10 The microbiological, epidemiological characteristics of peritonitis are important determinants of clinical outcome. Race, previous peritonitis, low residual glomerular filtration rate, long PD duration, diabetes, higher body mass index, constipation and diarrhoea, hypokalemia, hypoalbuminemia, invasive gastrointestinal procedures, poor dentition, vitamin D deficiency, depression and young age are potential risk factors for peritonitis.Citation11–14

The aim of this study was to examine the peritonitis rates, causative organisms and the risk factors of peritonitis in a large group of patients in our centre.

Methodology

The study was conducted in the Nephrology Department of a University Hospital in Turkey. Patients with ESRD in the PD programme between January 2000 and January 2006 were included. The demographic, clinical and microbiological data of the patients were evaluated retrospectively. The patients who were transferred from PD to HD or who had transplantation and then returned to PD during the study period were excluded. All of the patients had double-cuff silastic Tenckhoff catheter that was implanted with the standardized surgical method.

The diagnosis of peritonitis was based on at least two of the following criteria: abdominal pain and cloudy effluent, effluent white blood cell count >100/mL, (after a dwell time of at least two hours), with at least 50% polymorphonuclear neutrophil cells or positive Gram stain or culture of effluent as recommended by the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD).Citation15 Before 2003, bacterial culture of the effluent had been performed with only conventional techniques and starting from the beginning of 2003 BACTEC (Becton Dickinson) automatized bottles were used along with conventional techniques. Organisms detected by culture were identified with standard microbiological techniques.

All of the patient charts and records were reviewed retrospectively for their demographical details including age, gender, etiology of ESRD, socioeconomic status, prior dialysis modality, transplantation history, PD duration, number of peritonitis episodes, catheter-related infections, causative organisms, antimicrobial therapy protocols and whether they are on automated-peritoneal dialysis (APD) or not. Comorbidities such as hypertension (HT), coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes mellitus (DM), peripheral artery disease (PAD) and cirrhosis were recorded.

Cohort-specific peritonitis incidence, subject-specific peritonitis incidence and peritonitis-free survival were calculated between 2000 and 2006. The causative organisms and peritonitis rates were assessed in total and for the time intervals 2000–2003 and 2003–2006. The potential risk factors for peritonitis were analyzed.

Statistical method

The incidence of peritonitis was calculated with three different methods: (1) Cohort-specific peritonitis incidence: the total number of peritonitis episodes in the population, divided by the total number of units of observation time (in patient-month or patient-year). (2) Subject-specific peritonitis incidence: the ratio of number of peritonitis episodes to treatment time for each patient. The median value indicates the number of peritonitis episodes seen in 50% of patients per unit of time. (3) Peritonitis-free survival: the time to first episode of peritonitis for 50% of the patients. When using this method only the patients who start on PD in the given time were considered.

Statistical analysis was performed using “SPSS (Standard Package for Social Sciences) for windows” (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Trends were analyzed using linear regression and the other changes were analyzed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact correction when required. The level of significance was set to a p value less than 0.05. To identify independent risk factors, covariates that have shown significance in univariate analysis were introduced in a multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 440 patients who were on PD between the years 2000 and 2006 were included for analysis. The mean age of the patients was 46.3 ± 16.8 and 45.9% of the patients were female (n = 202; ). Totally 620 episodes of peritonitis occurred over the six years period in 12,013 patients-months and 1001 patient-years, whereas 61.6% (n = 271) of the patients had at least one episode of peritonitis.

Table 1. The demographical and clinical characteristics of the patients.

Cohort-specific peritonitis incidence was 0.62 episodes/patient-years. In every 19.4 patient-months one episode of peritonitis occurred. The median subject-specific peritonitis incidence was 0.44 episodes/patient-years. In every 15.6 patient-months one episode of peritonitis occurred. When we consider the 317 patients who started PD during the study period, the median peritonitis-free survival was 15.25 months (%95 CI, 9.45–21.06 months). The comparison of different models of peritonitis rates is summarized in .

Table 2. The comparison of different models of peritonitis rates (2000–2006).

Between 2000 and 2006, coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CoNS) was the most commonly encountered organism among all microorganisms identified as etiological agents (17.1%, n = 106). In general, 37.6% (n = 233) of the peritonitis episodes were caused by gram-positive organisms, 12.7% (n = 79) of them were caused by gram-negative organisms and only 0.5% (n = 3) of them were caused by fungi (). The proportion of culture negative peritonitis was 49.2% (n = 305; ).

Table 3. Causative organisms and their percentages between the time periods.

Patients were divided into two groups according to time period to examine the trends through the years. During the time period 2000–2003, 330 patients had a total of 5753 patient-months, 479 patients-years on PD. In this period, 377 peritonitis episodes occurred of which cohort-specific peritonitis incidence was 0.79 episodes/patient-years. In every 15.2 patient-months one episode of peritonitis occurred. On the other hand, during the time period 2003–2006, 304 patients had a total of 6393 patient-months, 533 patient-years on PD. In this period 243 peritonitis episodes occurred, cohort-specific peritonitis incidence was 0.46 episodes/patient-year. In every 26.3 patient-months one episode of peritonitis occurred.

When the spectrum of causative organisms between these two periods was compared, the distribution of the causative organisms differed. During the time period 2000–2003 the most common causative organism was CoNS (18.6%, n = 70), while 36.3% (n = 137) of the total 337 peritonitis episodes were caused by gram-positive organisms, 9.8% (n = 37) were caused by gram-negative organisms and 0.8% (n = 3) were caused by fungi (). Culture-negative peritonitis was 53.1% (n = 200; ). During the time period 2003–2006 the most common causative organism was again CoNS (14.2%, n = 36), while 39.5% (n = 96) of the total 243 peritonitis episodes were caused by gram-positive organisms, 17.3% (n = 42) of them were caused by gram-negative organisms (). Culture-negative peritonitis was 43.2% (n = 105; ). There was a significant difference in the percentage of culture negative peritonitis between the time periods (p = 0.01).

While the percentage of E. coli was 2.4% during the time period 2000–2003 it has reached to 11.5% during the time period of 2003–2006 (p < 0.001). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli was isolated in 2 (22.2%) patients during the time period 2000–2003 and in five (17.9%) patients during the time period 2003–2006 and this decrease was not statistically significant (p = 0.79). The total percentage of ESBL-producing E. coli was 18.9% in this cohort.

The percentage of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci (MRCoNS) peritonitis was 5.3% during the time period 2000–2003 which reached 12.8% during the time period 2003–2006 (p = 0.001; ).

Subgroup analyses were done with regards to certain factors cited in . When diabetic (n: 86, 19.5%) patients were compared to non-diabetics (n: 354, 80.5%) it was seen that 55.9% of the diabetic patients had at least one episode of peritonitis while 63% of the non-diabetics patients had at least one episode of peritonitis (p = 0.219). We divided the patients as ≥60 years (n: 106, 24.1%) and < 60 (n: 334, 75.9%) for further evaluation. Although 57.5% of the patients that were 60 years and older, 67.9% of the patients that were younger than 60 years had at least one peritonitis episode, this difference was not significant (p = 0.326). When we compare APD (n: 59, 13.4%) and CAPD (n: 38, 86.6%) patients, 61.4% of the patients on CAPD had at least one peritonitis episode whereas 62.7% of the patients on APD had at least one peritonitis episode. This was also not found significant (p = 0.849). Another analysis was done grouping patients as patients who had prior HD therapy (n: 251, 43%) and who had only PD therapy (n: 189, 57%): 69.3% of the patients who had prior HD therapy had at least one peritonitis episode while 51.3% of the patients who had only PD therapy had at least one peritonitis episode and this difference was significant (p < 0.001).

We compared the factors that might pose a risk for peritonitis between the patients who had at least one episode of peritonitis (271 patients, 61.6%) and who had no peritonitis episode (169 of the patients, 38.4%). The mean age of patients who had peritonitis was 46.2 ± 15.8 and who had no peritonitis episode was 46.7 ± 18.3 (p = 0.76). In univariate analysis; HCV infection without cirrhosis, HBV infection without cirrhosis, level of literacy, prior HD therapy (at least six months), catheter-related infection were found to be significant but when we introduce them into a multivariate logistic regression model, HBV infection and level of literacy were not found to be significantly related to peritonitis incidence. Prior HD therapy (at least more than six months), catheter-related infection and HCV infection without cirrhosis were found to be independent risk factors (). Age, gender, etiology of ESRD, duration of ESRD, level of literacy, DM, CAD, PAD, cirrhosis and HBV infection were not found to be significant in univariate analysis.

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with peritonitis.

Discussion

Peritonitis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality for patients on long-term PD therapy. The introduction of the Y-set in 1979 and advances in catheter technology lead to a decline in overall peritonitis rates throughout the years.Citation16,Citation17 In our study, we also showed that the cohort-specific peritonitis rates decreased from 0.79 episodes/patient-years in 2000–2003 to 0.46 episodes/patient-year in 2003–2006. The cohort-specific peritonitis incidence was 0.62 episodes/patient-year and in every 19.37 patient-months one episode of peritonitis occurred. This rate is considerably low when compared to the studies in the literature. In a study of Kavanagh et al. in The Scottish Renal Registry, it was reported that in every 19.2 patient-months one episode of peritonitis have occurred.Citation18 In another study of Boehm et al., it was reported that in every 14.6 patient-months one episode of peritonitis have occurred.Citation12 Although there are lower rates like 0.29–0.23 episodes/patient-year in the literature, in our centre it was found below the limits that were recommended to be no more than one episode every 18 months (0.67/year at risk) in a centre by International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis 8ISPD).Citation15,Citation19,Citation20 The decreasing trend in peritonitis rates in years 2000–2003 and 2003–2006 might be a result of the new training programme started in 2003 at our centre which a PD nurse was actively involved in teaching at every visit. Continuous active training in aseptic techniques and proper response to contamination helps to prevent peritonitis. In a study comparing the outcomes of training and retraining in randomized PD patients who was given standard training or advanced training, they found a decline in the catheter related infection and peritonitis rate in the advanced training group after two years.Citation21

It is important to choose the right method in calculating the peritonitis rates. The conventional cohort-specific peritonitis incidence shows the total peritonitis incidence and its general importance in a PD population. It can’t assign a personal peritonitis risk. In our patient population there is a very small group that had one peritonitis episode in every 19.37 patient-months; in contrast there is a large group that never had peritonitis and a group that had peritonitis more frequently. Hence it’s more appropriate to use median subject-specific peritonitis incidence that shows the distribution more accurate in our population, the patients observed shorter than the peritonitis free survival time should be excluded. Another limiting issue is that it cannot be applied to the populations in which more than 50% subjects experience peritonitis.Citation22

When we examine the causative organisms, the proportion of gram-positive organisms was greater in 2003–2006 (39.5%) than in 2000–2003 (36.3%) but it was not statistically significant (p = 0.239). The proportion of gram-negative organisms was 9.8% in 2000–2003, which have increased to 17.3% in 2003–2006, and it was statically significant (p = 0.005). This increase is caused by the increased proportion of E. coli, which was 2.4% in 2000–2003 and reached to 11.5% in 2003–2006 (p < 0.001). The increase in the proportion of gram-negative organisms in the last years is attributed to intra-abdominal pathologies of PD patients like diverticulitis. In a study of Kim et al. they also reported an increase in the proportion of gram-negative organisms in the 2000s.Citation19

Another issue is the increase in antibiotic resistance. Especially the incidence of MRCoNS has increased by time. The incidence of MRCoNS, which was 5.3% in 2000–2003, has reached to 12.8% in 2003–2006 (p = 0.001). This increase might be due to our empirical antibiotic regimen. Lyytikainen et al. and Zelenitsky et al. reported an increase in the incidence of MRCoNS similarly.Citation23,Citation24 In the literature there are studies suggesting the use of empirical vancomycin rather than cephazolin but this can lead to an increase in the incidence of organisms such as vancomycin resistant staphylococci and enterococci.Citation25,Citation26 Thus, every center should make an empirical therapy strategy considering their own resistance patterns.

The rate of culture negative peritonitis which was 53.1% in 2000–2003, decreased to 43.2% in 2003–2006 (p = 0.01). The changing of the culture techniques that we use in our centre played an important role in it. Before 2003 we were using only solid agar media for isolation but our centre started to use automated blood culture system, BACTEC system (Becton Dickinson) in 2003. Thus, inoculation of specimens into both solid agar and blood culture bottles yielded fewer culture negative results. Despite the decrease in the culture-negative peritonitis rate it is still higher than the suggested rate, 20%, by ISPDCitation15 and there are some resources suggesting a lower rate than 10% as well.Citation27 Even though it is difficult to explain the high incidence in a retrospective study, the high rates of culture-negative peritonitis might be due to inappropriate culture methods and techniques like inadequate sampling and incubation period and the use of antibiotics prior to visits to our PD unit. In our country, due to relative high prevalence of tuberculosis and brucellosis than developed countries these infections should be kept in mind in culture negative peritonitis. This high proportion of culture-negative peritonitis could lead to misinterpretation of the results as a limitation.

When we evaluate the risk factors for peritonitis, we found that prior HD therapy (at least more than six months) increased the risk of peritonitis by 1.76-fold (p = 0.029). The immune system of patients on HD is suppressed and HD accesses raise the risk of bacteremia. In the patients who had these procedures before PD therapy, hematogenous spread of organisms might be the pathogenesis of peritonitis but there are not sufficient data about it in the literature. There is a risk of indication bias with prior HD therapy as HD patients may have been on dialysis for longer time and have worse healthy condition but we didn’t find any difference in peritonitis incidence according to ESRD duration of the patients. This result may be another compelling factor for the PD first approach with the findings in the literature that infection-related complications are steadily declining in PD patients over the past decade whereas they are increasing in HD patients and HD compared with PD as an initial modality doubles the risk for hospitalization for septicaemiae.Citation28

Catheter-related infection is found to be another risk factor of peritonitis in our study; it increases the peritonitis risk 4.05-fold (p = 0.001). Especially when there is S. aureus and P. aeruginosa peritonitis, catheter-related infection should be kept in mind. S. aureus nasal carriage is seen common in catheter related infections.Citation29

We found that HCV infection without cirrhosis is a risk factor for peritonitis. HCV infection increases the risk of peritonitis 2.84-fold (p = 0.005). In a univariate analysis, HBV infection was found to be a risk factor but when we analyze it with a multivariate model we found it non-significant. In a study by Chow et al., they observed a relatively high peritonitis rate in the cohort with positive hepatitis B surface antigen than hepatitis B-negative counterparts, irrespective of cirrhosis status.Citation30 There are no more available data in the literature.

In conclusion, advances in the technologies lead to a decrease in the peritonitis rates but effective training of the patient about catheter care and PD techniques still play an important role in the prevention of PD peritonitis. Patient training is the most important issue for decreasing the peritonitis rates, especially for catheter-related infections. The correct management of samples for culture is important in lowering culture negative peritonitis rates. Every centre should monitor their peritonitis rates periodically and evaluate causative organisms and antibiotic resistance in order to make changes in the empirical therapy strategies if necessary. The finding that patients with HCV infections are at increased risk of peritonitis requires attention, as further prospective studies are needed to evaluate the risk factors.

Declaration of interest

There is no support and financial disclosure. There is no conflict of interest. The authors state that this manuscript has not been published previously and is not currently being assessed for publication by any other journal.

References

- Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, Garg AX. Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. JASN. 2012;23(3):533–544

- Bloembergen WE, Port FK, Mauger EA, Wolfe RA. A comparison of mortality between patients treated with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. JASN. 1995;6(2):177–183

- Johansson N, Kalin M, Giske CG, Hedlund J. Quantitative detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae from sputum samples with real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction for etiologic diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;60(3):255–261

- Suleymanlar G, Serdengecti K, Altiparmak MR, Jager K, Seyahi N, Erek E. Trends in renal replacement therapy in Turkey, 1996–2008. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(3):456–465

- Fried LF, Bernardini J, Johnston JR, Piraino B. Peritonitis influences mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. JASN. 1996;7(10):2176–2182

- Woodrow G, Turney JH, Brownjohn AM. Technique failure in peritoneal dialysis and its impact on patient survival. Perit Dial Int. 1997;17(4):360–364

- Choi P, Nemati E, Banerjee A, Preston E, Levy J, Brown E. Peritoneal dialysis catheter removal for acute peritonitis: A retrospective analysis of factors associated with catheter removal and prolonged postoperative hospitalization. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(1):103–111

- Piraino B, Bernardini J, Sorkin M. Catheter infections as a factor in the transfer of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients to hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1989;13(5):365–369

- Rubin J, Rogers WA, Taylor HM, et al. Peritonitis during continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(1):7–13

- National Institutes of Health CAPD Registry. 1987. Report from the Data Coordinating Center at the EMMES Corporation P, Md., and the Clinical Coordinating Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

- Golper TA, Brier ME, Bunke M, et al. Risk factors for peritonitis in long-term peritoneal dialysis: The Network 9 peritonitis and catheter survival studies. Academic Subcommittee of the Steering Committee of the Network 9 Peritonitis and Catheter Survival Studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28(3):428–436

- Boehm M, Vecsei A, Aufricht C, Mueller T, Csaicsich D, Arbeiter K. Risk factors for peritonitis in pediatric peritoneal dialysis: A single-center study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(10):1478–1483

- Chow KM, Szeto CC, Leung CB, Kwan BC, Law MC, Li PK. A risk analysis of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25(4):374–379

- Piraino B, Bernardini J, Brown E, et al. ISPD position statement on reducing the risks of peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Perit Dial Int. 2011;31(6):614–630

- Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(4):393–423

- Maiorca R, Cancarini G. Thirty years of progress in peritoneal dialysis. J Nephrol. 1999;12(Suppl 2):S92–99

- Strippoli GF, Tong A, Johnson D, Schena FP, Craig JC. Catheter-related interventions to prevent peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. JASN. 2004;15(10):2735–2746

- Kavanagh D, Prescott GJ, Mactier RA. Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis in Scotland (1999–2002). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(10):2584–2591

- Kim DK, Yoo TH, Ryu DR, et al. Changes in causative organisms and their antimicrobial susceptibilities in CAPD peritonitis: A single center's experience over one decade. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24(5):424–432

- Li PK, Law MC, Chow KM, et al. Comparison of clinical outcome and ease of handling in two double-bag systems in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(2):373–380

- Finkelstein ES, Jekel J, Troidle L, Gorban-Brennan N, Finkelstein FO, Bia FJ. Patterns of infection in patients maintained on long-term peritoneal dialysis therapy with multiple episodes of peritonitis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(6):1278–1286

- Schaefer F, Kandert M, Feneberg R. Methodological issues in assessing the incidence of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis in children. Perit Dial Int. 2002;22(2):234–238

- Lyytikainen O, Vaara M, Jarviluoma E, Rosenqvist K, Tiittanen L, Valtonen V. Increased resistance among Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates in a large teaching hospital over a 12-year period. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15(2):133–138

- Zelenitsky S, Barns L, Findlay I, et al. Analysis of microbiological trends in peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis from 1991 to 1998. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(5):1009–1013

- Agraharkar M, Klevjer-Anderson P, Rubinstien E, Galen M. Use of cefazolin for peritonitis treatment in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 1999;19(5):555–558

- Vas SI. VRE and empirical vancomycin for CAPD peritonitis: use at your own/patient's risk. Perit Dial Int. 1998;18(1):86–87

- Physicians RAaRCo, ed. Treatment of Patients with Renal Failure: Recommended Standards and Audit Measures. 3rd ed. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2002

- Chaudhary K, Sangha H, Khanna R. Peritoneal dialysis first: rationale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(2):447–456

- Nouwen J, Schouten J, Schneebergen P, et al. Staphylococcus aureus carriage patterns and the risk of infections associated with continuous peritoneal dialysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2233–2236

- Chow KM, Szeto CC, Wu AK, Leung CB, Kwan BC, Li PK. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in patients with hepatitis B liver disease. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26(2):213–217