Abstract

Background: Immunological dysfunctions and a pro-inflammatory environment are associated with higher risk of cardiovascular diseases in chronic kidney disease (CKD). Physical exercise can be an important anti-inflammatory strategy, but the effects in CKD remain poorly investigated. Objective: Evaluate the acute inflammatory response to intradialytic exercise in the peripheral blood of individuals with CKD. Methods: Nine patients, of both genders, with CKD and allocated in the ambulatory of hemodialysis of Hospital Ernesto Dornelles (Brazil), performed two sessions of hemodialysis (HD) in random form: aerobic intradialytic exercise sessions (EX, 20 min of moderate exercise in cycle-ergometer) and a control hemodialysis session (CON). Peripheral blood collection was made at the baseline, during and immediately after HD to evaluate the cytokine profile: interleukin-6, interleukin-10 (IL-10), interleukin-17a (IL-17a), interferon-gamma (INF-γ) and tumoral necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Results: INF-γ decreased during HD when compared with the pre moment in both sessions, while an increase in post HD was only found in the CON session. IL-17 was higher in post when compared with during HD in both sessions. In addition to the time effect, IL-10 presented a time × group interaction and the relative changes were significantly higher in EX when compared with the CON session. The relative changes in TNF-α tended to be higher in CON when compared with EX immediately post HD session. Conclusions: These data indicate that 20 min of intradialytic exercise have modest effect in systemic inflammation. However, the significant increase in IL-10 may indicate an immunoregulatory effect of physical exercise.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) refers to the progressive and irreversible decline in renal function and is a consequence of several dysfunctions, such increase in visceral adiposity, hypertension and diabetes.Citation1 An increase in the rates of CKD occurs in many countries across the world, and in the USA, 10% of people over the age of 20 have some degree of CKD. This condition is associated with an increase in approximately 59% of mortality when compared with patients without CKD.Citation2 The chronic inflammatory state in CKD occurs through a complex dysfunction able to influence both innate and adaptive immunological systems. Progressive renal injury alters the elimination of metabolites, resulting in local and systemic stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, through exposure to endotoxin and reduced excretion, due to changes in renal filtration.Citation1 Furthermore, chronic hemodialysis (HD) can stimulate the intracellular pattern of inflammatory mediators.Citation1,Citation3 As a result, the development of a chronic inflammatory state is associated with certain conditions such as muscle atrophy, malnutrition, chronic infections and atherosclerotic processes, and major causes of morbidity and mortality.Citation4

Cytokines are glycoproteins with low molecular weight, secreted in response to antigens, danger signals or others chemical messengers and that regulate many immunological aspects across pro- or anti-inflammatory activities.Citation5 In CKD, there is an increase in the systemic concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).Citation6 Regarding interleukin-10 (IL-10), a cytokine with greater anti-inflammatory aspects and regulatory activities, data show that its levels are elevated due to reduced excretion, but the secretion by regulatory T lymphocytes are impaired.Citation3,Citation6

Due to its anti-inflammatory potential, physical exercise can be a promising therapy, able to modulate these parameters in CKD.Citation7 Furthermore, it is noteworthy that both acute and regular physical training are related to increased functional capacity,Citation8 improvement of endothelial functionCitation9 and increased quality of lifeCitation10 in patients with CKD.

Despite this, studies evaluating the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise in CKD are still scarce, especially in regard to the effects of intradialytic exercise, that is, exercise during the HD session. Intradialytic exercise refers to an exercise session performed during HD, with lower drop-out rate and greater compliance.Citation11 Furthermore, intradialytic exercise increases the rate of solute and toxins removal by the dialyzers.Citation11 Thus, the objective of this study is to evaluate the acute inflammatory response in intradialytic exercise in peripheral blood of patients with CKD.

Methods

Patients

This study was conducted in a crossover clinical trial where subjects performed two HD sessions in different conditions (described below) with an interval of one week. All patients were fully informed of the experimental procedures and signed a free and informed term, and this study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Centro Universitario Metodista IPA and Hospital Ernesto Dornelles (Porto Alegre, Brazil), (protocol 305.395). None of the participants were smokers or used glucocorticoids within a four-week period of data collection and were instructed to refrain from ingesting alcohol or caffeinated beverages in a period of 48 h prior to the experimental procedures and 24 h after the exercise session.

Patients of both genders with a diagnosis of CKD who perform HD at a frequency of three sessions per week, for at least three months, in the Hemodialysis Service of Hospital Ernesto Dornelles (Porto Alegre, Brazil) were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were: severe cardiovascular disease, lower limb amputation, cognitive disorders, musculoskeletal or osteoarticular lesions and femoral fistula, which would prevent completion of the exercise session. Before the experimental trials, patients had their body mass and height determined by a semi-analytical scale (Welmy, Santa Barbara d’Oeste/Brasil), their abdominal circumference (AC) and the body mass index (BMI) were calculated.

Experimental procedures

Six-minute walk test

The six-minute walk test (6MWT) was performed in a 30-m long track with measurements every 10 m marked on the ground. Prior to the beginning of the test, patients were instructed about the purpose and implementation of the test and advised to reduce the rhythm or stop if they had symptoms such as chest pain, respiratory distress or internal muscle pain; however, the timer would not be stopped if any of these events occurred. All subjects received verbal stimuli to help them complete the test. HR and SpO2 were measured by pulse oximetry (model 1001 Morrya, São Paulo, Brazil) and perceived exertion by the Modified Borg Scale (data not shown). Once six minutes elapsed, the test evaluator recorded the distance traveled by the volunteer with an open 20-m tape measure. The 6MWT followed the recommendations established by the American Thoracic Society (2002).

Exercise and control sessions

The protocols used in the study were performed in the afternoon on the second day of HD of the week. All patients were randomly assigned to two sessions with one week of interval between each session. The HD procedures in both sessions were performed in a proportion machine, “Fresenius”, with polysulfide membranes. In CON, subjects performed a conventional HD session lasting four hours, without exercise.

EX was conducted by a physiotherapist and consisted of an HD session with aerobic exercise on lower limb cycle ergometer (Ergo-bike, Cardio 2002 PC, Dream electronic, Germany) which was positioned in front of the patient. Physical exercise was performed after the first two hours of HD, with a duration of 20 min. Patients were asked to maintain speed performance equivalent to 6 or 7 in the Modified Borg Scale.Citation12 Vital signs were monitored during HD, and after the session patients underwent stretching of the lower limbs muscles.

Blood sampling and analysis

For the inflammatory modulation analyses, 8 mL of venous blood were collected from the antecubital vein into tubes without anticoagulant in pre-hemodialysis, immediately after the exercise for EX session or the equivalent time to the CON session (during HD) and immediately after the HD session for both groups (post HD). Serum samples were separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 1048 g (2500 rpm), divided into aliquots, and frozen at −20 °C for further analysis.

The systemic levels of IL-6, TNF-α, interferon-γ (INF-γ), interleukin-17 A (IL-17A) and IL-10 were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with specific kits (Mini ELISA Development Kit, 900-M21, PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) and following the manufacturer’s recommendations. To avoid errors due to intra-assay sensitivity, all cytokine’s analyses were performed on the same plate on the same day. Briefly, plates of 96 wells were incubated overnight with capture antibody, anti-IL-6, IL-10, IL-17a, INF-γ or TNF-α diluted in 1 × PBS buffer. After blocking for 1 h to avoid non-specific binding, 100 μL of standard IL-6, IL-10, IL-17a, INF-γ or TNF-α and serum samples were placed. The cytokines were detected by horseradish peroxidase-labeled monoclonal antibody to each target after the addition of 100 μL anti-human IL-6, IL-10, IL-17a, INF-γ or TNF-α biotinylated antibodies, they were placed in each well and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The microplate was washed to remove unbound enzyme-labeled antibodies. The amount of horseradish peroxidase bound to each well was determined by the addition of 100 μL substrate solution. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μL of 1 M sulfuric acid, and the plates were read at 450 nm (ThermoPlate, São Paulo, Brazil). The concentrations of cytokines were determined by interpolation from standard curve and presented as pg/mL. Due to the clearance of blood fluid during HD, the changes in plasma volume as well the cytokine concentrations were calculated from measurements of hemoglobin and hematocrit, according to the method described by Dill and Costill.Citation13

Statistical analyses

For descriptive statistics, the data were presented in mean (95% confidence interval) or mean ± standard deviation; data were checked for normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test, homogeneity of variance, and sphericity, before statistical analysis. Baseline values were initially compared using a Student’s t-test for independent data. A two-way repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized, considering time (PRE, DURING, POST) and session (EXERCISE or CON) as factors. When appropriate, a post-hoc Bonferroni test was applied for multiple comparisons over time within the session. The relative changes from (pre – during) and (pre – post) HD were also measured by two-way repeated measures ANOVA using Bonferroni’s post-hoc. For all tests, the level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05 and the statistical package used was SPSS 20.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY). The effect size (ES) was used to determine the magnitude of changes between evaluations of the protocols.Citation14 Threshold values for recreationally trained individuals were <0.35 (trivial), 0.35–0.8 (small), 0.8–1.50 (moderate) and >1.5 (large).Citation14

Results

In this study, five (55.6%) individuals were of black ethnicity, seven (77.8%) were female and four (44.4%) had diabetes mellitus as an associated disease. The individual and mean of demographic characteristics of patients are presented in .

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients with CKD.

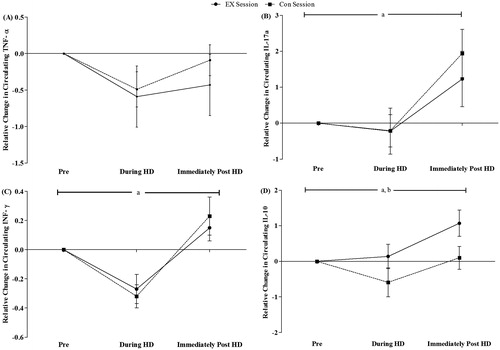

presents the cytokine concentrations in CON and EX sessions in the moments pre, during and post HD. At baseline, no significant differences between sessions (p > 0.05) were found. ANOVA shows main effect for time in IL-17A (p = 0.003), INF-γ (p = 0.001) and IL-10 (p = 0.004). The post-hoc analysis indicated that IL-17A was significantly higher in immediately post HD when compared with during HD in EX (p = 0.012, ES = 1.14) and CON (p = 0.005, ES = 1.94) sessions. INF-γ presented significant differences in during-immediately post HD (p = 0.048, ES = 1.31) comparison in EX session, while the CON session showed lower levels of INF-γ during HD when compared with the pre (p = 0.04, ES = 1.21) and immediately post HD (p = 0.006, ES = 1.74) moments, respectively. An elevation of the IL-10 levels was found in PRE-POST (p = 0.05, ES = 0.16) and during-immediately after (p = 0.044, ES = 0.82) comparison in EX session, but in the CON session only the during-immediately after (p = 0.05, ES = 1.89) comparison was different. ANOVA also showed a time × group interaction (p = 0.018), but no group effect (p > 0.05) in IL-10. No effects in IL-6 and TNF-α (p > 0.05) were found.

Table 2. Cytokine response to endurance exercise intradialysis (EX) or control hemodialysis (CON) in peripheral blood of patients with CKD.

We also compared the relative changes (during – pre and immediately post – pre) of cytokine levels between sessions (). EX and CON sessions showed higher values immediately post HD in comparison to during HD in IL-17a (p = 0.004 for EX, ES = 0.67; p = 0.001 for CON, ES = 1.20), INF-γ (p = 0.01 for EX, ES = 1.44; p = 0.001 for CON, ES = 1.53) and IL-10 (p = 0.015 for EX, ES = 0.86; p = 0.004 for CON, ES = 0.62). A tendency for significance was found when comparing the relative changes of TNF-α during and immediately post HD in CON session (p = 0.06, ES = 0.58), with no difference in the EX session (p > 0.05). Main effect for session (p < 0.05) also was found in IL-10, and relative change of IL-10 immediately post EX group tended to higher when compared with CON session (p = 0.07). No significant differences were observed in IL-6 (p > 0.05).

Discussion

It is well established that CKD presents notable immunological dysfunctions which result in a chronic inflammatory disease.Citation3,Citation15 Physical exercise is described as an important anti-inflammatory therapy in treatment and prevention of many chronic degenerative diseases.Citation7 In accordance, in the present study intradialytic exercise session modulated IL-10, IL-17a, INF-γ and TNF-α levels on peripheral blood of the individuals.

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the acute response of the systemic cytokines to intradialytic exercise in individuals with CKD. A significant elevation of the serum IL-10 was observed at the end of the EX session and interaction time × group in IL-10, a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine due to effects in inhibiting the activation of the pro-inflammatory patterns of monocytes/macrophages (M1 pattern) and T lymphocytes (Th1 pattern), and the expression of co-stimulatory molecules such as MCH.Citation16 Our results can be related to those obtained with healthy individuals, where anti-inflammatory cytokines present a significant elevation in endurance exercises with moderate or high intensities.Citation17

The physiological importance of increasing this cytokine in CKD is associated with anti-atherogenic properties such as reduction of monocytes adhesion and vascular calcification, interfering in the development of atherosclerosis processes and other cardiovascular diseases.Citation18

The elevations of INF-γ and IL-17A are involved in the pathogenesis of CKD, development of atherosclerosis lesion and associated with the end stage of renal disease.Citation19 Our study indicates that intradialytic exercise was not able to regulate the serum elevation of these cytokines in CKD. However, in healthy subjects, acute moderate exercise can attenuate the pro-inflammatory pattern of many immune cells, especially, the Th1 and Th17 patterns.Citation20 It is known that HD sessions can elevate the inflammatory response.Citation3 Therefore, we suggest that another protocol, characterized by larger volume or duration, might improve these cytokines.

In addition, we demonstrated a tendency, though not significant, toward reduction of TNF-α at the end of EX session. Similar to our data, Lau et al.Citation21 found only trends for an increase in IL-6 concentrations and ratio IL-6:TNF-α, and decrease in TNF-α in pediatric CKD who performed moderate exercise at 50% of peak oxygen consumption. Acute modulations in systemic TNF-α remain controversial, and this response is linked to the volume of the exercise performed.Citation22

In CKD, for Viana et al.,Citation23 30 min of aerobic exercise in pre-dialysis individuals induced significant elevation of IL-6 and IL-10, with little effect in the TNF receptors (sTNF-RI and sTNF-RII) in post exercise. After one hour from the exercise session, IL-6 and IL-10 remained in higher concentrations and an increase in sTNF-RII was found. When considered together, these findings support the idea of the anti-inflammatory potential of the exercise in CKD.

These effects are attributed, at least in part, to myokines express elevations, glycoproteins like cytokines express by the muscle tissue during and after physical exercise, such IL-6.Citation24 In spite of being a pro-inflammatory cytokine, it is well established that physical exercise can induce an increase in Il-6 expression, showing metabolic and anti-inflammatory effects which stimulate the synthesis and expression of other anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1ra and IL-10 and reduces the nuclear-kappa beta factor (NF-κB).Citation25

IL-6 is chronically elevated in CKD,Citation18 but the effects in post-exercise seem to be more beneficial than harmful. In the present study, the lack of significant increase in IL-6 may also be related to the intensity and duration of the workout, since the magnitude of the increase appears to be protocol-dependent and determined by the combination of the type, intensity and duration of the exercise performed.Citation25

Most importantly, the same anti-inflammatory effect observed in this study and othersCitation23,Citation26 has not been observed in studies involving systematic physical training for over 12 weeks. They did not observed any changes in the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β or C-reactive protein.Citation27,Citation28 Nonetheless, there was an enhancement of functional capacity through aerobic exercise which was associated with the reduction of inflammatory state in CKD, and can be a secondary effect of rehabilitation programs.Citation29

Some limitations of this study should be mentioned: the relatively small sample size may lead to a statistical type I error; and the intensity of the exercise in EX session was performed using perceived exertion, which might affect adversely the control of the exercise. However, the lack of consensus in the literature and the absence of specific guidelines for intradialytic exercise creates difficulties to determine an appropriate intensity for CKD.

In conclusion, we suggest an acute anti-inflammatory effect of intradialytic exercise through modulation of IL-10 and some pro-inflammatory cytokines in peripherical blood of CKD individuals through modulation of IL-10 and some pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is possible these effects may contribute to reducing the high risks of cardiovascular and metabolic events existing in CKD patients. Nevertheless, additional studies are needed to elucidate the complex relationship between CKD and immune dysfunctions.

Declaration of interest

Financial support came through the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (PROSUP/CAPES/Brazil). A.P. also thanks the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the grant (MCTI/CNPQ/Universal 14/2014). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carrero JJ, Axelsson J, Avesani CM, Heimburger O, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P. Being an inflamed peritoneal dialysis patient: A Dante’s journey. Contrib Nephrol. 2006;150:144–151

- U.S. Renal Data System. 2012 Annual data report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States [webpage on the Internet]. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/atlas12.aspx

- Bitla AR, Reddy PE, Manohar SM, Vishnubhotla SV, Pemmaraju Venkata Lakshmi Narasimha SR. Effect of a single hemodialysis session on inflammatory markers. Hemodial Int. 2010;14:411–417

- Eleftheriadis T, Antoniadi G, Liakopoulos V, Kartsios C, Stefanidis I. Disturbances of acquired immunity in hemodialysis patients. Sem Dial. 2007;20:440–451

- Nakayamada S, Takahashi H, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ. Helper T cell diversity and plasticity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(3):297–302

- Pachaly MA, do Nascimento MM, Suliman ME, et al. Interleukin-6 is a better predictor of mortality as compared to c-reactive protein, homocysteine, pentosidine and advanced oxidation protein products in hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2008;26:204–210

- Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, Lindley MR, Mastana SS, Nimmo MA. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: Mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:607–615

- Kosmadakis GC, Bevington A, Smith AC, et al. Physical exercise in patients with severe kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;115:c7–c16

- Headley S, Germain M, Wood R, et al. Short-term aerobic exercise and vascular function in CKD stage 3: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(2):222–229

- Lima MC, Forgiarini LA, Monteiro MB, Dias AS. Effect of exercise performed during hemodialysis: Strength versus aerobic. Renal Fail. 2013;35:697–704

- Sheng K, Zhang P, Chen L, Cheng J, Wu C, Chen J. Intradialytic exercise in hemodialysis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2014;40:478–490

- Porszasz J, Casaburi R, Somfay A, Woodhouse LJ, Whipp BJ. A treadmill ramp protocol using simultaneous changes in speed and grade. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1596–1603

- Dill DB, Costill DL. Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37:247–248

- Rhea MR. Determining the magnitude of treatment effects in strength training research through the use of the effect size. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18:918–920

- Yamamoto T, Nascimento MM, Hayashi SY, et al. Changes in circulating biomarkers during a single hemodialysis session. Hemodial Int. 2013;17:59–66

- Saraiva M, O’Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(3):170–181

- Shojaei EA, Farajov A, Jafari A. Effect of moderate aerobic cycling on some systemic inflammatory markers in healthy active collegiate men. Sci Sports. 2011;26(1):298–302

- Stenvinkel P, Kettleler M, Johnson RJ, et al. IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-alpha: Central factors in the altered cytokine network of uremia – the good, the bad, and the ugly. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1216–1233

- Ge S, Hertel B, Koltsova EK, et al. Increased atherosclerotic lesion formation and vascular leukocyte accumulation in renal impairment are mediated by interleukin-17A. Circ Res. 2014;113:965–974

- Kakanis MW, Peake J, Brenu EW, Simmonds M, Gray B, Marshall-Gradisnik SM. T helper cell cytokine profile after endurance exercise. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014;34:699–706

- Lau KK, Obeid J, Breithaupt P, et al. Effects of acute exercise on markers of inflammation in pediatric chronic kidney disease: A pilot study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;30(4):615–621

- Nieman DC, Konrad M, Henson DA, Kennerly K, Shanely RA, Wallner-Liebmann SJ. Variance in the acute inflammatory response to prolonged cycling is linked to exercise intensity. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32(1):12–17

- Viana JL, Kosmadakis GC, Watson EL, et al. Evidence for anti-inflammatory effects of exercise in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(9):2121–2130

- Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: Focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(4):1379–1406

- Welc SS, Clanton TL. The regulation of interleukin-6 implicates skeletal muscle as an integrative stress sensor and endocrine organ. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:359–371

- Donges CE, Duffield R, Smith GC, Short MJ, Edge JA. Cytokine mRNA expression responses to resistance, aerobic, and concurrent exercise in sedentary middle-age men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(2):130–137

- Cheema BSB, Abas H, Smith BC, et al. Effect of resistance training during hemodialysis on circulating cytokines: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:1437–1445

- Daniilidis M, Kouidi E, Fleva A, et al. The immune response in hemodialysis patients following physical training. J Sports Sci Health. 2004;1:11–16

- Shiraishi FG, Stringuetta Belik F, Martin LC, et al. Inflammation, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease: Role of aerobic capacity. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:750286