The differentiation of infectious and noninfectious etiologies of uveitis has always been a major concern for uveitis specialists. In patients with previous systemic infection with tuberculosis (TB) and a concurrent history of noninfectious uveitic entities, a definite diagnosis can sometimes be rather elusive. Here, we report a 10-year perplexing course of panuveitis in a patient with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and a history of TB.

A 20-year-old woman presented with an insidious onset painless chronic iritis for 6 months in both eyes (BE) treated elsewhere in 2000. Nongranulomatous keratic precipitates, posterior synechiae, and secondary glaucoma, complicated by cataracts with blurred fundi, were noted. Visual acuity (VA) was 20/100 (BE). She had been diagnosed with pauciarticular JIA by a pediatric rheumatologist at the age of 15 years, with an unremarkable result of ophthalmic screening at diagnosis only once. Pulmonary and spinal TB was noted when she was 18 years old, for which she received 12 months of complete treatment. No ocular symptoms were noted during that hospitalization.

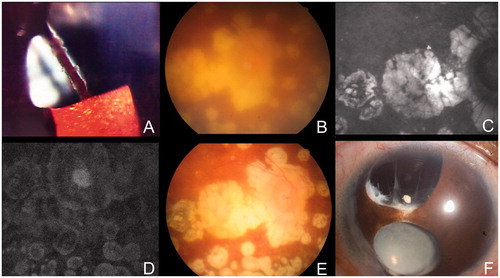

JIA-related iritis was first suspected. Trabeculectomy with peripheral iridectomy done in 2000 (right eye, RE) allowed much improved pressure control. Meanwhile, systemic methotrexate and a topical steroid were administered. Only intermittent low-grade anterior chamber reaction (BE) was noted in the following 3 years. However, lens capsule rupture was noted in 2003, with aggravated iritis (RE). Cataract extraction without intraocular lens (IOL) implantation was initially attempted. However, upon the patient's request to avoid a secondary operation, simultaneous in-the-bag IOL implantation was done (RE). Postoperative inflammation control was satisfactory with an intensive topical steroid, a systemic steroid 0.5 mg/kg, and methotrexate. Six months later, cataract surgery with IOL implantation was done on the left eye (LE) with preoperatively silent anterior chamber, with the same strategy of perioperative medications. Systemic steroid was tapered off in postoperative 2 months (BE). One month after left eye cataract surgery, biomicroscopy revealed trace iritis, multiple punched-out chorioretinal scars (), and vitreous opacity but without vitritis, indicating previously disseminated choroiditis (BE). Her VA improved to 20/40 (BE) by the age of 24 years. However, fresh granulomata along the peripheral iridectomy margin (RE) (), increased iridocyclitis (LE), and vitreous haze (BE) were noted 7 months later. Apart from the initial nongranulomatous presentation, this new granulomatous profile raised the suspicion of active panuveitis. Fluorescein angiography was of poor quality due to vitreous haze. However, a diffuse vasculitis pattern was slightly visible. Strong positivity (21 mm) was shown on a tuberculin skin test (TST). Anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) with isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide was therefore initiated, and methotrexate was withheld. However, iridocyclitis became more aggravated 4 weeks later. An anterior-chamber (AC) tap for acid-fast stain and TB-PCR was negative. Methotrexate was resumed and the ATT was discontinued.

FIGURE 1. Clinical course of the case presented. (A) Granulomata along the peripheral iridectomy margin (RE) at the age of 24 years. (B) Disseminated chorioretinal punched-out patches (RE) at the age of 24 years. (A) + (B) raised the suspicion of ocular tuberculosis. (C, D) The infrared and fluorescein angiography images disclosed punched-out scars without active leakage (RE). (E) Considerably clearer vitreous opacity with dry chorioretinal scars after 18 months of anti-tubercular treatment at the age of 30 years (RE). (F) Corectopia with anterior capsule fibrosis at the age of 30 years (RE).

A careful retrospective review of this situation suggests that both the discontinuation of methotrexate per se and application of ATT could have played roles in the outburst of intraocular inflammation. The presumed Jarisch-Herxheimer-like reaction, with the manifestation of aggravated iridocyclitis and chorioretinitis, has been noted weeks to even 3 months after antibiotic treatment.Citation1,Citation2 In this sense, stepwise adjustment of medications, in which adding anti-TB drugs while keeping methotrexate or an adjunctive systemic steroid, should have been considered. This strategy might not only eliminate the confounding effects of methotrexate withdrawal but also bring about beneficial results in reducing the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction.

Under the control of methotrexate and topical steroid, intermittent low-grade iritis ensued for the next 4 years. VA gradually dropped to 20/100 (BE). The fundus appearance remained similar. Due to another episode of increased AC reaction, a granulomatous uveitis workup was performed at the age of 26 years old. Whole-body single-photon emission computed tomography and serological studies excluded diagnoses of sarcoidosis or syphilis. AC tap for TB-PCR remained negative. Application of an intensive topical steroid successfully controlled the inflammation. However, another outbreak at the age of 28 years old warranted reinvestigation. TST showed a 21-mm induration. Fluorescein angiogram disclosed diffuse punched-out scars without leakage (). Interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) (QuantiFERON-TB Gold) was positive. Therefore, ATT was administered for 18 months. Iridocyclitis gradually abated 12 months after initiating ATT and concurrent low-dose systemic steroid (0.5 mg/kg/day). Methotrexate was discontinued. However, her VA gradually deteriorated to LP (RE) and NLP with phthisic changes (LE) at the age of 30 years old.

During this second therapeutic challenge, the clinical effect was greatly delayed, at 12 months. Conceivably, relative immunosuppression with methotrexate could have contributed. However, whether prolonged ATT, administered during the previous episode when she was 18 years old, had resulted in drug-resistance remains unknown. Nevertheless, an 18-month course, as suggested by infectious disease specialists, was completed. According to Basu and colleagues, nearly one-quarter of patients with TB uveitis might develop progressive intraocular inflammation following ATT. The majority of them resolved with escalation of systemic steroid.Citation2 In the current case, ATT with concurrent systemic steroid, although delayed, indeed brought about the final quiescence of panuveitis.

JIA-related uveitis is the primary disease entity in pediatric uveitis, with the classic manifestation of chronic nongranulomatous iridocyclitis.Citation3 Adult onset,Citation4 granulomatous presentation,Citation5 and even chorioretinopathy,Citation6 although all have been reported in the literature, are considered unusual. Ocular presentation of tuberculosis can be protean.Citation7 If not treated appropriately with systemic TB chemotherapy, it can run a relapsing–remitting course, with ultimate chorioretinal destruction and a poor prognosis.Citation8 Chronic iridocyclitis with posterior synechiae is not uncommon in the two disease entities discussed. Therefore, in the absence of initial granulomatous presentation and with a lack of a clear fundal view, the differential diagnosis can be perplexing.

In the case presented, initial nongranulomatous presentation, satisfactory disease control with a topical steroid and systemic methotrexate were compatible with the clinical impression of JIA-related uveitis. Nevertheless, the widespread chorioretinal patches with increased vitreous haze and iris granulomata detected postoperatively strongly implied the underlying pathology other than JIA. At the same time, the clinical profiles of broad-base posterior synechiae and serpiginoid choroiditis were highly consistent with Gupta and associates' description of tubercular uveitis.Citation9

The TST has traditionally been the most widely used test due to its simple and economic nature. However, operator errors, prior vaccinations, and the immunological status of the subject can all contribute to confounding results. Firstly, while bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination in infancy has virtually no influence on the TST done in adulthood, inoculation beyond infancy substantially contributes to a false-positive reaction on single TST, or false-positive conversion on repeated TST weeks to even 1 year apart (the “booster phenomenon,” often defined as an increased induration >6 mm).Citation10 Taiwan has given a BCG vaccination to all newborns since 1965. If TST was negative in elementary school, repeated injection was done. This strategy inevitably affects the TST results. Secondly, clinical risk factors and the prevalence of diseases in a certain area have to be carefully evaluated. For example, according to CDC guidelines in the United States, >5 mm induration is considered positive in HIV-infected individuals, those exposed to active TB, or those with radiographic evidence of healed TB lesions; with the extreme size of induration, >15 mm of induration is considered positive among subjects without risk factors.Citation11 Overall, the test has shown only fair sensitivity (71%), with suboptimal specificity (65–70%) and a low positive prediction rate (5–10%).Citation12

IGRA has been utilized extensively for the past few years. It offers comparable sensitivity (66%) but with much greater specificity (85–99%) and much less confounding by vaccination.Citation13 Nevertheless, both tests utilize the reaction of sensitized memory T cells against TB.Citation12 Therefore, active or latent infection and previous TB infection/reactivation could not be effectively differentiated with either test. In the current case, positive TST and IGRA possibly only disclosed immunologic memory in such a BCG-vaccinated individual with prior active TB infection less than 3 years ago.

When these aforementioned tests failed to provide conclusions, TB-PCR seemed to be the last resort. However, variable sensitivity (21–78%) has been reported for the currently available single-primer PCR.Citation14 A negative result by no means excludes a diagnosis. Singh and associates analyzed the vitrectomy samples in Eales disease with quantitative PCR. In their Eales disease cohort, 57% of samples were positive for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome.Citation15 Vitrectomy with chorioretinal lavage and biopsy, which was of both diagnostic and therapeutic value, were therefore considered in the current case. However, it was not performed due to the aggressive nature. Finally, therapeutic trial with ATT was warranted in this clinical context. Unfortunately, Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction and delayed clinical response had made the diagnosis challenging.

In summary, the case was reported of a young adult with concurrent JIA and a recent history of TB infection who presented with panuveitis. JIA-related iridocyclitis was first suspected. However, the diagnosis was questioned due to sequentially noted multifocal chorioretinopathy and iris granulomata, which are rarely seen in JIA-related uveitis. Ocular TB was strongly suspected three times (). Nevertheless, all of the ancillary tests failed to provide definite conclusions. Anti-TB therapeutic trials were performed twice, with Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction and delayed clinical response, respectively. These results further puzzled the clinicians. Delayed diagnosis and treatment thus contributed to a poor visual prognosis.

TABLE 1. Clinical suspicions of ocular tuberculosis and subsequent workup results.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Cheung CM, Chee SP. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: paradoxical worsening of tuberculosis chorioretinitis following initiation of antituberculous therapy. Eye. 2009;23:1472–1473

- Basu S, Nayak S, Padhi TR, Das T. Progressive ocular inflammation following anti-tubercular therapy for presumed ocular tuberculosis in a high-endemic setting. Eye. 2013;27:657–662

- Vitale AT, Graham E, de Boer JH. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: clinical features and complications, risk factors for severe course, and visual outcome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013

- Camuglia JE, Whitford CL, Hall AJ. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis in adults: a case series. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:330–334

- Keenan JD, Tessler HH, Goldstein DA. Granulomatous inflammation in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. J AAPOS. 2008;12:546–550

- Thacker NM, Demer JL. Chorioretinitis as a complication of pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2005;42:183–184

- Yeh S, Sen HN, Colyer M, et al. Update on ocular tuberculosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:551–556

- Hamade IH, Tabbara KF. Complications of presumed ocular tuberculosis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:905–909

- Gupta A, Bansal R, Gupta V, et al. Ocular signs predictive of tubercular uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:562–570

- Menzies D. What does tuberculin reactivity after bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination tell us? Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:S71–S74

- Jasmer RM, Nahid P, Hopewell PC. Clinical practice: latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1860–1866

- Schluger NW. Advances in the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:60–66

- Diel R, Goletti D, Ferrara G, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:88–99

- Mehta PK, Raj A, Singh N, Khuller GK. Diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by PCR. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;66:20–36

- Singh R, Toor P, Parchand S, et al. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in so-called Eales' disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2012;20:153–157