Abstract

In Italy family is characterized by strong ties and is based on mutual aid of all its members. In the last 20 years, the structure of families has been significantly influenced by demographic, economic and professional changes, determining a transition from a patriarchal to a nuclear family model, with a higher number of single-parent families, single-person households, childless couples, same-sex couples. However, this transition has been slower than that occurring in other countries, probably as an ongoing impact of prevalent Catholic ideology. Major demographic changes in Italian families include, 1) a decrease in the number of marriages, delays in getting married and an high number of civil ceremonies, 2) a reduced birth rate; Italy is becoming one of the European countries with lowest growth rate, and with an increasing number of births out of wedlock, 3) an increased marital instability, with a constantly growing number of legal separations. Like many countries, relatives in Italy are highly involved in the care of patients with physical and mental disorders. There are a number of psychosocial interventions used in Italy including the ‘Milan Systemic Approach’ and family psycho-educational interventions. However, there are difficulties in implementing these interventions which are highlighted in this paper. We recommend research strategies to identify the best options to involve families in the care of mentally ill patients and to adequately support them.

Introduction

The National Institute of Statistics recently defined the family as ‘all persons related by marriage, kinship, affinity, adoption, guardianship, cohabiting and having their usual residence in the same municipality’ (ISTAT, Citation2011). This definition is very different from the first official definition of the family included in the Italian Constitution, according to which the family is ‘a natural society founded on marriage’ (Italian Constitution, 1949). This radical change reflects a deep modification in family structure that has occurred in Italy since the late 1950s.

The demographic and structural changes in the economic and professional models have significantly modified family structure, promoting the transition from a patriarchal to a nuclear family model. The shift to “nuclear family” model, made by spouses and one child, all contributing to the financial provision of the family and with less strong ties, has been helped by several factors such as: 1) the affirmation for equal rights and opportunities of the spouses; 2) the achievement of high levels of education and 3) the need to move to different regions to find a job.

Moreover, alongside this traditional family model, other types of ‘modern family’ have recently developed in Italy as they have in other countries. In fact single-parent families, single person households, childless couples, same-sex couples were virtually non-existent until 10 years ago. Homosexual unions in Italy are not yet legally permitted, and it is not possible to know the extent of this phenomenon, since these unions have not been considered in previous population censuses. The development of new family models has been significantly slowed by Roman Catholic ideology, which continues to have a very strong influence on Italian attitudes and thus on families.

In Italy family members are usually involved in the care of mentally ill patients, in particular following the reform law adopted in 1978 (de Girolamo et al., Citation2007). Before this law, families were often partially involved in the care process of mentally ill patients. Moreover, the current legislation for family protection outlines the need to provide incentives for relatives who take care of patients with long-term disease. In the national health plan, the assessment of family burden and the provision of family supportive interventions are reported among government priorities.

Studies in Italy have evaluated family burden associated with caregiving in both physical and mental disorders such as heart disease, diabetes, renal and lung disease (CitationMagliano et al., 2005). These authors have also shown that not entirely surprisingly, care-giving itself is associated with anxiety, depression, financial difficulties, restriction of daily activities, and other effects on relatives’ physical health. For this reason, several attempts have been made to increase the availability of supportive family interventions in Italy, but their routine availability is still very patchy across the country.

The Italian family

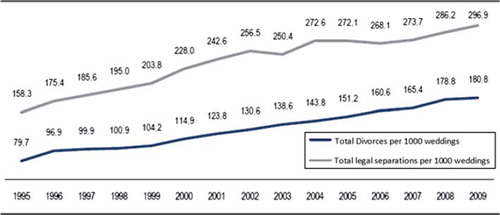

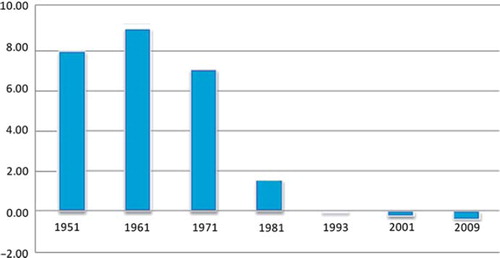

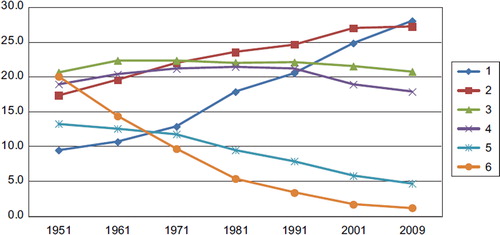

Population growth has registered a negative balance in Italy since the early 1990s () (ISTAT, Citation2011). Currently, ‘zero population growth’ also seems to be a reality in Italy. If the total number of citizens has not yet decreased this is only because of the massive migration that has occurred in the last 10 years (De Rose, 2008; ISTAT, Citation2010). Moreover, another major change that occurred recently in Italy is the reduction in the mean number of family members per family (e.g. in 1951 a typical Italian family included 4 members, in 2009 only 2.4 members (ISTAT, Citation2010)), although the total number of Italian families (including those with only one member) has increased ( and ).

Figure 1. Population growth rate (in thousands) (ISTAT, Citation2011).

Figure 2. Number of families in Italy (in millions) (ISTAT, Citation2011).

Figure 3. Number of family members (%) (ISTAT, Citation2011).

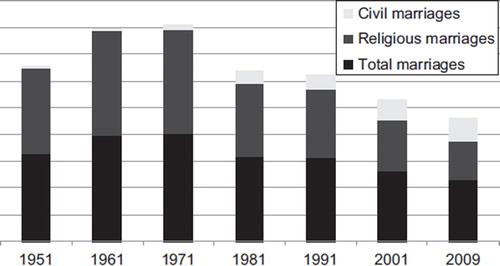

In the past 20 years several changes have occurred in family behaviours. These include, 1) decreased marriage rates, delays in weddings and these occurring at older ages, and a growing number of civil ceremonies; 2) low birth rates: Italy has one of the lowest fertility rates in Europe and also has an increasing number of births out of wedlock; 3) increased marital instability, with legal separations. and show major changes that have occurred in recent years regarding attitudes of the Italian population.

Figure 4. Total civil and religious marriages in Italy since 1951 (ISTAT, Citation2011).

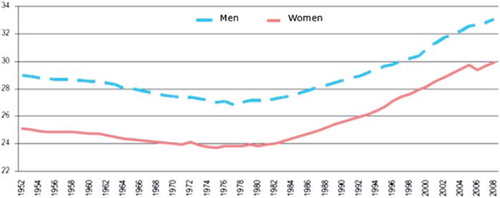

Figure 5. Mean age at marriage since 1952 (ISTAT, Citation2009).

Several factors have been identified as contributing to a reduction in inclination to get married. These include high number of years spent in education and the increased work opportunities for women, and the loss of the social role of marriage, coupled with scepticism towards institutions and welfare policies in both sexes (Rosina & Fraboni, Citation2004).

Whilst the National Institute of Statistics reports a progressive decline of the ‘traditional’ family in favour of new forms of family, if we compare Italian marriage and divorce rates with those of other central and northern European countries, we see that this is not so evident. In fact, marriage in Italy still remains very important. Italian society has generally less favourable attitudes towards unions that differ from the traditional wedding (Rosina & Fraboni, Citation2004). This could be due to the presence of the Catholic Church (Goody, Citation2000) along with a strong cultural traditionalism towards family and marriage, as confirmed by the delay in the introduction of the law on divorce in 1971. In fact, the Catholic Church has a strong influence in maintaining the idea that family is a ‘social unit based on natural law’ (Bimbi, Citation1999), with a consequent non-acceptance of new structures of families and a slow development of modern policies regarding family issues, such as the right to divorce, abortion, the equal opportunities agreements between women and men, the right to maternity, and the law on parity (Bimbi, Citation1997).

Another important social change is that fewer people in Italy tend to marry and if they do, they do so later in life than 20 years previously ().

Mean age for marriage was 35 for men and 32 for women in 2010, while it was 29 for men and 26 for women in 1990. This delay has an important consequence: the sharp reduction in new births (Mazzucco et al., Citation2006). In fact, the Italian fertility rate is among the lowest in the world. The total fertility rate (PTFR) was below 2 children per woman in 1977, below 1.5 in 1984 and below 1.3 in 1993 (De Rose et al., Citation2008). In 2011 in Italy 46% of families have only one child (43% in 1984), and 42.8% have two children (43.5% in 1984). Nevertheless, the number of abortions is decreasing. Births outside wedlock are relatively few among the different age groups, despite the tendency of teenagers to have their first sexual relationship earlier than had been reported in the past (Caltabiano et al., Citation2006).

Regional variations in the number of children per family still exist. In central and in northern Italy there are a high number of families without children, more one-child families, and a high mean age at first child. In southern Italy, there is a prevalence of two-children families and a relatively higher proportion of numerous families (CitationBarbagli et al., 2003). However, a convergence in these issues among Italian regions can be observed in recent years (De Rose et al., Citation2008).

Factors said to be associated with the low number of births are, 1) the increase of family costs (De Santis & Livi Bacci, 2001), 2) the lack of gender balance in domestic tasks and childcare (Ongaro, 2002), 3) the lack of labour market flexibility for women (ISTAT Citation2004), 4) the absence of family policy reforms promoting childbearing (De Sandre, Citation1997; Saraceno, Citation1994).

Modifications in family structures in Italy have not generally followed European standards. This is probably due to strong cultural and social factors, according to which children leave their parental household only when they get married. Moreover, the Catholic Church has probably influenced the attitudes of Italians to have children only within marriage (Dalla Zuanna, Citation2011).

In 2011 divorce occurs in Italy in around 10% of marriages. Second marriages are more frequent in northern and central Italy regions. Typically, men tend to marry for a second time more often than women.

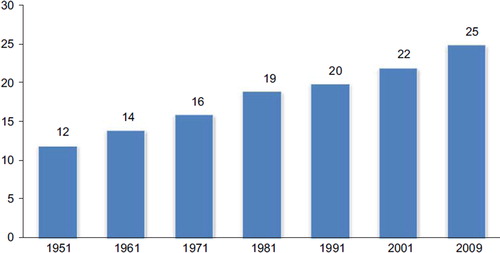

In Italy divorces are continuously increasing () as are informal unions, especially among younger generations. In 2009 the total number of divorces was 269 per 1000 inhabitants (ISTAT, Citation2009), a value consistently lower than those of other European countries, where the considerable increase in marriage dissolutions is a consequence of the general revolution in behaviour regarding sexual relationships and common law marriages.

However, divorce itself cannot be used as the only indicator of the frequency of marital dissolution, since legal separation is considered to be the crucial point when dealing with marital conflicts according to Italian law. Divorce is simply considered to be the final stage of the process of separation (De Rose, Citation1992). The low frequency of separations can be attributed to several factors including, 1) the pressure exerted by Catholic beliefs on Italian society and on personal decisions, 2) the slowness and uncertain legal processes and the extremely high legal costs (Bimbi, Citation1999).

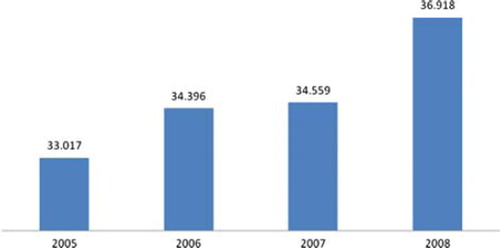

A new trend in the modern Italian family composition is the presence of marriages where one of the spouses is of foreign nationality. This phenomenon is still not yet well developed, but has progressively increased over the past five years. Typically, in mixed marriages the husband is Italian, and the female spouse is of foreign nationality ().

Figure 7. Weddings with at least one foreign spouse (thousands) (ISTAT, Citation2009).

Therefore, in Italy, the family is still characterized by strong ties and greater intergenerational support. The great importance given to the family in Italy is also reflected in the quality of care provided in cases of disease that affect the whole family.

Increasing attention is being paid in recent years to family problems, as demonstrated by the large number of family therapists and counsellors, family associations, and training centres spread throughout the country.

In the following section we describe treatments offered to the family currently available in Italy.

Family care of psychiatric patients in Italy

Given the still relatively strong families ties, in Italy, family members are often involved in the care of patients with physical or mental disorders. As regards psychiatry, one of the most important consequences of the reforms was that most mentally ill patients live in close contact with their families, which represent the primary resource for their social integration (Fiorillo et al., Citation2011a). Nevertheless, empirically supported psychosocial treatments to address family difficulties in living with mentally ill patients (e.g. cognitive behavioural techniques, psycho-educational interventions, interpersonal psychotherapy, family therapy) have not achieved a wide diffusion (Lasalvia et al., Citation2011). It has been shown that the implementation of psychosocial family interventions in Italian mental health centres (MHCs) is hampered by several difficulties, such as the need to integrate the intervention with other work responsibilities, the lack of time to run structured interventions and the paucity of resources (CitationMagliano et al., 2006b).

A recent study, funded by the Ministry of Health and coordinated by the Department of Psychiatry, University of Naples SUN, found that in a sample of 709 relatives of patients with schizophrenia, whilst 80% of them are in regular contact with mental health staff, 59% attended informative sessions on the patient's illness and its treatment and 43% received adequate information on how to cope with the patient's disturbing behaviours, only 8% of them received an evidence-based supportive intervention such as psycho-education (CitationMagliano et al., 2002). The poor availability of this intervention documented by this study is common to other European and US countries, where the percentage of families receiving psycho-educational interventions ranges between 0 and 15% (Dixon et al., Citation2001; Fadden & Heelis, 2011; Gonçalves-Pereira, Citation2006; Torrey, Citation2001).

There are two influential interventions developed in Italy to address family difficulties. The first is that developed by Mara Selvini-Palazzoli in the early 1970s, known and studied in Italy and abroad as the ‘Milan Systemic Approach’ (Selvini-Palazzoli, Citation1975). The second is the family psycho-educational intervention, which in Italy has been adopted in the treatment of schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar disorder, disseminated in Italy starting from the research experience of the universities of Napoli, L’Aquila and Milan. Studies carried out in these universities have demonstrated the effectiveness of these interventions in reducing family burden, lowering relapse rates and improving social outcome in schizophrenia (CitationCasacchia & Roncone, 1990; Invernizzi et al., 1990; Magliano et al., Citation2006a).

Psycho-educational family intervention

As in other European countries, family psycho-educational interventions have rapidly spread in Italy, considering the vast amount of promising results on their effectiveness coming from the American experience (Goldstein et al., Citation1978). The most commonly used approach in Italy is that of Falloon et al. (Citation1982), which has the following objectives, 1) to provide the family with information about the patient's disorder and its treatments, 2) to improve communication patterns within the family, 3) to enhance the family's problem-solving skills, 4) to improve relatives’ coping strategies, and 5) to encourage relatives’ involvement in social activities outside the family (Fiorillo & Galderisi, Citation2011; Solomon & Cullen, Citation2008). According to this approach, the intervention is provided in single-family format, with inclusion of patients. The intervention should last six months, with weekly sessions. According to the results of the early studies on the effectiveness of this intervention in schizophrenia, this approach, provided together with the pharmacological treatment, has also been successfully used in families of people with other mental disorders such as major depression (Fiorillo et al., 2001b; Luciano et al., 2012) and bipolar disorder (Del Vecchio et al., Citation2011). The results of these studies highlight the effectiveness of this intervention in reducing family burden and improving the social outcomes of patients and their relatives, but have also pointed out the difficulties in using this intervention in the routine care of mental health service users, especially for the organizational architecture of MHCs and for the structure of the intervention that can be an obstacle to the implementation of this intervention in Italian MHCs (Del Vecchio et al., Citation2011; CitationMagliano et al., 2006b). Studies on the use of shorter approaches of these interventions are currently ongoing (Luciano et al., Citation2010).

Systemic family therapy

As noted above, systemic family therapy was developed very early in Italy, especially through the work of Mara Selvini-Palazzoli who described a specific model of family therapy, now internationally known and applied by many family therapists around the world (Bennun, Citation1986; Bressi et al., Citation2004; Mashal, Citation1989; Selvini-Palazzoli et al., Citation1975; Shadish et al, Citation1995).

In 1981, Luigi Boscolo and Gianfranco Cecchin founded the Milan Centre for Family Therapy. They systematized a method of conducting family therapy sessions and developed the therapeutic process named the Milan Approach. In the last few years they have been among the main protagonists of the re-establishment of the clinic system in light of second-order cybernetics, constructivism and social constructionism, and suggested, among other things, a clinical approach focused on the prejudices and emotions of the therapist. Currently, this approach can be learned in different private schools in Italy (Milan, Bologna, Genoa, Padua, Palermo, Turin, Treviso and Trieste). The training lasts four years, with a total of 2000 hours (1440 hours of theoretical lessons and 560 of practical training with a dedicated supervisor) and is suitable for medical doctors as well as psychologists.

Family supportive interventions for physical diseases

In Italy family support is now provided to caregivers in managing a number of organic disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and dementia, stroke, Parkinson's disease (CitationBartolo et al., 2010) and oncological disease. In particular, the progressive establishment of hospices as a place of care for terminal cancer patients has allowed the development of a multidisciplinary model of care for terminally ill patients, which includes psychological support to the family (CitationCacioppo, 2006). Unfortunately in Italy there is a huge imbalance in the geographical distribution of hospices for terminally ill patients. In fact, these nursing homes are completely absent in some Italian regions, and in general are more distributed in the northern region of the country (Ministry of Health, Citation2006).

Family care in paediatrics

Paediatric care in Italy has also started to pay attention to family issues. In Italy, family orientated care in paediatrics may be considered equivalent to the institution of the ‘family paediatrician’, which is part of the public health system (Pettoello-Mantovani, Citation2007). Furthermore, the Italian Ministry of Health explored the possibility to establish the paediatric ‘Casa della Salute’, which was designed to be an institution somehow comparable to the Medical Home typical of the English speaking medical system, where a particular emphasis is given to the care of children and their parents (Pettoello-Mantovani et al., Citation2009). The“Casa Della Salute” is an integrated inpatient unit were children and their relatives are provided with medical visits and psychosocial interventions. Several health and social workers constitute a “team” in order to optimize the quality of care provided. Nevertheless, studies documenting the effectiveness of family-orientated interventions addressed to relatives’ difficulties in care-giving in paediatrics are scarce (Centre for Family Therapy, Milan, Citation2012).

Conclusions

In Italy in the last 20 years a slow but gradual modification in the family structure, relationships and composition has been observed. However, in comparing changes in Italy with those of other European countries, it appears that in spite of rapid economic changes after World War II, the social structures have remained relatively static, especially regarding the organization of the family, the school system, and women's time schedule of work (De Rose, 2008). Catholic ideology has played a major role in this process. Therefore, in Italy ‘family’ is still the fundamental social institution, characterized by strong ties, and based on mutual aid of all the family members.

The great importance given to the family from a social and anthropological viewpoint, however, is regrettably not reflected in healthcare, considering the low percentage of family involvement in healthcare of physical and mental disorders and resulting high levels of family burden. Furthermore, supportive family interventions are not routinely provided for both psychiatric and other physical diseases associated with high levels of disability.

Italy has a strong tradition in research in family therapy models such as psycho-educational family interventions and the family systemic therapy. However, research is still needed in order to implement family supportive interventions, especially in paediatric and physical disease, with the aim to address difficulties in caring within the family setting. More work is needed in identifying which components of family therapy work best with which type of family.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Barbagli, M., Castiglioni, M. & Dalla Zuanna, G. (2003). Building up a family in Italy. A century of changes. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Bartolo, M., De Luca, D., Serrao, M., Sinforiani, E., Zucchella, C. & Sandrini, G. (2010). Caregivers burden and needs in community neurorehabilitation. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 42, 818–822. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0612

- Bennun, I. (1986). Evaluating family therapy: A comparison of the Milan and problem solving approaches. Journal of Family Therapy, 8, 225–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1986.00719.x

- Bimbi, F. (1999). The family paradigm in the Italian welfare state (1947–1996). South European Society and Politics, 4, 72–88.

- Bimbi, F. (1997). Children care as a social benefit. A European perspectives of families policies. In C. Baraldi & G. Maggioni (Eds), Cittadinanza dei bambini e costruzione sociale dell’ infanzia (pp. 117–140). Urbino: Edizioni Quattro Venti.

- Bressi, C., Lo Baido, R., Manenti, S., Frongia, P., Guidotti, B., Maggi, L., … Invernizzi, G. (2004). Schizophrenia and the clinical efficacy of the systemic family therapy: a prospectic longitudinal study. Rivista di Psichiatria, 39, 3–9.

- Cacioppo, C., Morello, E., Casiraghi, L., Sandri, R. & Monfardini, S. (2009). Older cancer patients in an Italian hospice. Annals of Oncology, 20, 791–792. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp014

- Caltabiano, M., Dalla Zuanna, G. & Rosina, A. (2006). Interdependence between sexual debut and church attendance in Italy. Demographic Research, 14, 453–484.

- Casacchia, M. & Roncone, R. (1999). Family psycho-educational treatment in schizophrenia: Love for foreigners or application of evidence-based interventions? Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 8, 183–189.

- Centre for Family Therapy, Milan (2012). http://www.cmtf.it/via-leopardi/cose-il-cmtf/

- Committee on Hospital Care, American Academy of Pediatrics (2003). Family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics, 112, 691–697.

- Dalla Zuanna, G. (2011). Tacit consent: The Church and birth control in northern Italy. Population and Development Review, 37, 361–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00414.x

- De Girolamo, G., Bassi, M., Neri, G., Ruggeri, M., Santone, G. & Picardi, A. (2007). The current state of mental health care in Italy: Problems, perspectives, and lessons to learn. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 257, 83–91. doi:10.1007/s00406-006-0695-x

- Del Vecchio, V., Luciano, M., Malangone, C., Giacco, D., De Rosa, C., Sampogna, G., … Maj, M. (2011). Implementing family psycho-educational intervention for bipolar I disorder in 11 Italian mental health centres. Italian Journal of Psychopathology, 17, 277–282.

- De Rose, A. (1992). Socio-economic factors and family size as determinant of marital dissolution in Italy. European Sociological Review, 8, 71–91.

- De Rose, A., Racioppi, F. & Zanatta, A.L. (2008). Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behavior. Demographic Research, 19, 665–704.

- De Sandre, P. (1997) The formation of new families. In: Barbagli, M. & Saraceno, C. (Eds) The condition of families in Italy. Bologna: Il Mulino. PP 201–213.

- De Santis, G. & Livi Bacci, M. (2001). Reflections on the economics of the fertility decline in Europe. Paper presented at the Eureco conference: The Second Demographic Transition in Europe, Bad Herrenalb, Germany.

- Dixon, L., Mc Farlane, W.R., Lefley, H., Lucksted, A., Cohen, M., Falloon, I, … Sondheimer, D. (2001). Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services, 52, 903–910.

- Falloon, I.R.H., Boyd, J.L., McGill, C.W., Ranzani, J., Moss, H.B. & Gilderman, A.M. (1982). Family management in the prevention of exacerbation of schizophrenia: A controlled study. New England Journal of Medicine, 306, 1437–1440.

- Fiorillo, A., Bassi, M., de Girolamo, G., Catapano, F. & Romeo, F. (2011). The impact of a psycho-educational intervention on family members’ views about schizophrenia: Results from the OASIS Italian multi-centre study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57, 596–603.

- Fiorillo, A. & Galderisi, S. (2011). Family interventions for schizophrenia. In W. Fleischhacker & I. Stolerman (Eds), Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia. Houten: Springer. PP 103–109.

- Fiorillo, A., Malangone, C. & Del Vecchio, V. (2011). The effect of family psycho-educational interventions on patients with depression. European Psychiatry, 26, S1, 2209.

- Goldstein, M.J., Rodnick, E.H., Evans, J.R., May, P.R. & Steinberg, M.R. (1978). Drug and family therapy in the aftercare of acute schizophrenics. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35, 1169–1177.

- Gonçalves-Pereira, M., Xavier, M., Neves, A., Barahona-Correa, B. & Fadden, G. (2006). Family interventions in schizophrenia. From theory to the real world in Portugal today. Acta Medica Portugesa, 19, 1–8.

- Goody, J. (2000) The European Family: An Historico-anthropological Essay. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Invernizzi, G., Clerici, M., Bertrando, P., Bressi, C. & Cazzullo, C.L. (1990). Family expressed emotion. From research to therapeutic intervention. Minerva Psichiatrica, 31, 89–96.

- ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) (2004). Changes in womens’ life. Rome. Ministry for Equal Opportunities. Rome: Ministero per le pari opportunità. www3.istat.it/istat/eventi/2004/8marzo/notastampa.pdf

- ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) (2007). The measurement of families in population surveys. La misurazionedelle tipologie familiari nelle indagini di popolazione. www3.istat.it/dati/catalogo/20100802_00/

- ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) (2007). Family in Italy. A statistical dossier. Dossier statistico. www.ildialogo.org/famiglia/1207576983783_DossierISTAT.pdf

- ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) (2011). Census of the general population. http://www.istat.it/it/censimento-popolazione-e-abitazi/censimento-popolazione-2011/il-campo-di-osservazione.

- ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) (2009). Legal separations and divorces in Italy. www.istat.it/it/archivio/32711

- ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) (2010). National demographic balance. www.istat.it/it/archivio/28491

- Italian Constitution (1949). Article 29. Roma: Italia.

- Lasalvia, A., Boggian, I., Bonetto, C., Saggioro, V., Piccione, G., Zanoni, C., … Lamonaca, D. (2011). Multiple perspectives on mental health outcome: Needs for care and service satisfaction assessed by staff, patients and family members. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology. doi 10.1007/s00127-011-0418-0

- Luciano, M., Del Vecchio, V., Giacco, D., De Rosa, C., Fabrazzo, D.M. & Fiorillo, A. (2010). A brief family psychoeducational intervention for inpatient with severe mental disorder and their relatives: a pilot study. II National Thematic Conference of the Italian Society of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, L’Aquila. September, 16–18.

- Luciano, M., Del Vecchio, V., Giacco, D., De Rosa, C., Malangone, C., Fiorillo, A. (2012). A ‘family affair’? The impact of family psycho-educational interventions on depression. Expert Review Neurotherapy, 12, 83–92.

- Magliano, L., Fiorillo, A., De Rosa, C., Malangone, C., Maj, M. & the National Mental Health Project Working Group (2005). Family burden in long-term disease: A comparative study in schizophrenia versus physical disorders. Social Science and Medicine, 61, 313–322. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.064

- Magliano, L., Fiorillo, A., Malangone, C., De Rosa, C., Favata, G., Sasso, A., … Maj, M. (2006a). Family psycho-educational interventions for schizophrenia in routine settings: Impact on patients’ clinical status and social functioning and on relatives’ burden and resources. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 15, 219–227.

- Magliano, L., Fiorillo, A., Malangone, C., De Rosa, C., Maj, M. & the Family Intervention Working Group (2006b). Implementing psycho-educational interventions in Italy for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Psychiatric Services, 57, 266–269.

- Magliano, L., Marasco, C., Fiorillo, A., Malangone, C., Guarneri, M., Maj, M. & the Working Group of the Italian National Study on Families of Persons with Schizophrenia (2002). The impact of professional and social network support on the burden of families of patients with schizophrenia in Italy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 106, 291–298.

- Mashal, M., Feldman, R.B. & Sigal, J.J. (1989). The unraveling of a treatment paradigm: A followup study of the Milan approach to family therapy. Family Process, 28, 457–470. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1989.00457.

- Mazzucco, S., Mencarini, L. & Rettaroli, R. (2006). Similarities and differences between two cohorts of young adults in Italy: Results of a CATI survey on transition to adulthood. Demographic Research, 15, 105–146.

- Ministry of Health (2006). Hospice in Italia, prima rilevazione ufficiale. www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_803_allegato.pdf.

- Ongaro, F. (2002). Explanatory and socio-economic factors to understand the low fertility rates in Italy: implication for research. Paper presented at the 41st Conference of the Italian Statistical Society, 5–7 June.

- Pettoello-Mantovani, M. (2007). Family-centered and family oriented care in pediatrics. Medicina, 2, 98–104.

- Pettoello-Mantovani, M., Campanozzi, A., Maiuri, L. & Giardino, I. (2009). Family-oriented and family-centered care in pediatrics. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 35, 12. doi:10.1186/1824-7288-35-12.

- Rosina, A. & Fraboni, R. (2004). Is marriage losing its centrality in Italy? Demographic Research, 11, 149–172.

- Saraceno, C. (1994). The ambivalent familism of the Italian welfare state. Social Politics, 1, 60–82.

- Selvini Palazzoli, M., Boscolo, L., Cecchin, G. & Prata, G. (1975). from the bottom “Paradox and counter-paradox. A new model of family therapy in families with schizophrenic transaction. Milano: Feltrinelli.

- Shadish, W.R., Ragsdale, K., Glaser, R.R. & Montgomery, R.R. (1995). The efficacy and effectiveness of marital and family therapy: A perspective from meta-analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21, 345–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1995.tb00170.x

- Solomon, P. & Cullen, S.W. (2008). Psychiatric rehabilitation for achieving successful community living for adults with psychiatric disabilities. In A. Tasman, J. Kay, J.A. Lieberman, M.B. First & M. Maj (Eds). Psychiatry (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Torrey, W.C., Drake, R.E., Dixon, L., Burns, B.J., Flynn, L., Rush, J., … Klatzker, D. (2001). Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services, 52, 45–50.