Abstract

There have been numerous changes to the US family over the past several decades. Traditional family roles have changed, and the conception of what Americans consider a ‘family’ has likewise shifted with differing societal views regarding gender, gender roles, race, and ethnicity. This review examines demographics of the American family as well as a number of family therapies that have been historically and are presently used to treat family problems. We expect that with the changes present in US society, family therapies will need to continue to be sensitive and adaptive to these shifts in order to be effective.

Introduction

Over the last half-century, the USA has seen drastic shifts in family structure and the expectations of men and women within households. Men are no longer the sole breadwinners and women's roles are no longer limited to housework and child rearing. Women are now part of the paid workforce, and the added competition has forced both men and women to pursue advanced degrees in order to secure more specialized, higher-paying jobs (Bianchi, Citation2011). This has resulted in increased mean household income at the cost of family stability (Bianchi, Citation2011). The time constraints on employed women have made it difficult to have children, and among US women aged 40 to 44, 20% have never had children, double that of 30 years ago (Bianchi, Citation2011). Although divorce rates have stabilized since the 1980s, they continue to hover around 40–50% in terms of lifetime prevalence (Cherlin, Citation2010) and have created various family units that stray far from the traditional nuclear family.

According to the CitationUS Bureau of the Census (1998), a family is ‘a group of two persons or more (one of whom is a householder) related by birth, marriage, or adoption and residing together’. This classification accounts for two-parent, one-parent, and gay-and-lesbian families, but says nothing of the increasingly common extended family units often remaining after a divorce, or of unmarried, cohabitating couples. Moreover, the census minimally accounts for under-represented minority populations, such as Native Americans and Asian Americans, whose family units may further differ from the legal definition (Teachman et al., 2000). Such wide gaps in how we understand families in the USA speaks to the diversity and ever-changing dynamics of the country, and calls for a broader definition of the complicated relationships emerging between individuals and their loved ones.

This paper will look at current demographics of the US family as well as some of the past and present family therapies that have been used to treat family problems. The aim is to provide an overview of the current challenges facing US society through the lens of the family unit.

Structure of the US family

Demographic trends of family structure in the USA have shifted dramatically since the mid twentieth century due to a number of economic, political and social changes. Paul Glick, the founder of the field of family demography, engaged in most of his work from 1940 to 1960, a period in which the conventional linear family lifecycle (singlehood, married, bearing children, having an empty nest, retired, death/widowhood) was the norm (Cherlin, Citation2010).

In his 1988 review, Glick commented on changing family demographics with increases in divorce, remarriage, cohabitation, lone living, and lone parenting (Glick, Citation1988). This model was further developed in a review by Teachman et al. (2000). Their overview expanded Glick's model by placing greater emphasis on racial, ethnic, and social class diversity, divorce, remarriage, and the effects of economic stagnation (Cherlin, Citation2010). They recognized the multitude of family types in the USA, including two-parent families, one-parent families, cohabitating couples, gay and lesbian families, and extended-family households but were unable to comment on this diversity due to the limited comparable nationwide data available at the time (Teachman et al., 2000).

Cherlin (Citation2010) documented these demographic changes during the 2000s, discussing the ongoing separation of family and household through factors such as single-parent childbearing, dissolution of cohabiting unions, divorce, re-partnering, remarriage, and transnational immigrant families. Increase in ethnic diversity will continue to modify what has historically been defined as ‘United States culture’.

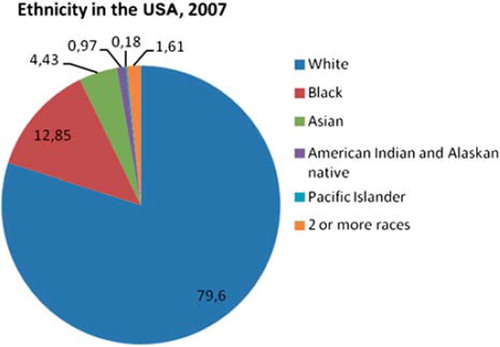

The US population is currently estimated to be over 313 million, of whom over 76% of the inhabitants live in cities, and among whom more than 50% are estimated to be suburban (CitationCIA, 2011). US ethnicity data is demonstrated in , though it is important to note that Hispanics are considered to be dispersed among these ethnic groups. An estimated 15.1% of the US population is Hispanic (CitationCIA, 2011).

Figure 1. Ethnicity in the USA, July 2007 estimate (CitationCIA, 2011).

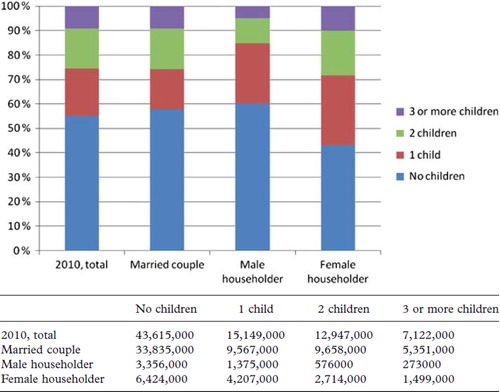

Family trends are continuing to change in the USA. More unmarried heterosexual couples, gay and lesbian couples, interracial couples, single women without male partners, and cohabiters are raising children. In addition, more mothers of young children are working outside the home, and more women are choosing not to have children altogether (Taylor et al., 2011b). The number of children in respective household types has been compiled in (CitationUS Bureau of the Census, 2012).

Figure 2. Family households by number of children 18 years and younger, 2000–2010 (CitationUS Bureau of the Census, 2012).

Though divorce rates sharply increased in the 1970s, they plateaued at high levels around 1980 and appear to be declining (Bianchi, Citation2011; Cherlin, Citation2010). Joshua Goldstein (Citation1999) proposed multiple factors contributing to this change: increase in the age of first marriage, increase in cohabitation ending doomed relationships prior to marriage, and aging baby boomers lengthening the statistical average duration of intact marriages. Divorce rates have diverged by educational status. Divorce probabilities decreased among married partners with college degrees and have stayed the same or increased among those with less education (Cherlin, Citation2010). This was consistent with Glick's non-linear relationship between divorce rates and education: divorce rates were lowest among white women who had completed educational tracks – later termed the ‘Glick effect’ (Glick, Citation1988).

Though divorce rates have stabilized overall, births to unmarried mothers have increased. These mothers are often romantically involved and/or cohabiting with the father at the time of the child's birth (Bianchi, Citation2011). A significant proportion of the increase in unmarried childbearing has occurred among cohabiting couples during time periods intended as steps toward or alternatives to marriage (Kennedy & Bumpass, Citation2008). However, 40% of cohabitating relationships and 80% of romantic relationships dissolved by the child's fifth birthday (McLanahan & Beck, Citation2010). While non-marital birthrates are also high throughout Europe, the USA is significantly notable for shorter relationship durations, a higher rate of relationship dissolution, as well as the lack of sustained paternal involvement in childrearing (Bianchi, Citation2011).

With the recent ‘Great Recession’ in the USA, shared housing has also been on the rise. Many factors have contributed to this trend toward multiple family housing and complex family households. First, people may be moving in with friends or family on an emergency basis. Second, families are home-sharing to decrease rent burden and increase residential desirability. Third, people who are unable to care for themselves, particularly the elderly, are entering new housing arrangements for assistance with activities of daily living. Fourth, people are choosing to live together for social connections and companionship (Elliott et al., 2011). Multigenerational households (two or more generations or ‘skipped’ generations) included a record-breaking 51.4 million individuals in 2009 (Taylor et al., 2011b). Cohabitation has doubled among certain age brackets since 1995 in both college-educated and non-college-educated individuals (Taylor et al., 2011a). As the baby boom generation reaches retirement age and becomes increasingly disabled, kin and quasi-kin relationships will likely result in an increase in family caregiving households (Cherlin, Citation2010).

Family therapy in the USA

Family therapies in the USA can be thought of in three generations. The first generation emerged in the mid 1950s with therapists such as Salvador Minuchin, Murray Bowen, and others who set the stage for later therapists in defining relationships, observing family functioning, and developing theories of change (CitationDoherty & McDaniel, 2010). Each focused on vastly different techniques. This review touches on strategic family therapy, systemic theory, and structural family therapy.

In strategic family therapy, the counsellor works to establish a therapeutic relationship with the family by joining with them to form a system, of which he becomes the leader. The counsellor also learns how the family interacts and takes advantage of those family interactions for therapeutic purposes. Once the relationship is developed, the parts of the system can work together to identify adaptive and maladaptive family interactions (CitationDoherty & McDaniel, 2010). Strategies for producing change include focusing on the present, reframing negativity in the family, shifting patterns of interaction through reversals of usual behaviour, changing family boundaries and alliances, ‘detriangulating’ family members caught in the middle of other's conflicts, and opening up closed family systems or subsystems by directing new interactions.

Systemic therapy, a form of family systems theory, is based around the idea that reality is constructed of social groups and takes a holistic approach to try to understand the pattern of interrelationships among the various systems (CitationKerr & Bowen, 1988). Causality is thus circular, thus promoting non-blaming of family members. Dialectical changes are obtained when there is an engagement of the therapist's and the family members’ differing views of the problem, creating a context in which contradictions and differences can emerge and challenge each other, thus producing change through opposition.

Structural family therapy, developed by Salvador Minuchin, is based on the theory that families have functions (mutual support, childrearing, etc.) and in order to carry out them out, the system needs leadership and boundaries (CitationDoherty & McDaniel, 2010). If the boundaries are too lax or too rigid, then problems may emerge. In this therapy, the therapist is very active, first establishing rapport, then assessing family patterns. This may be accomplished by changing the perceptions of the problem through homework assignments and enactments of family arguments during sessions with the goal of establishing new relational patterns between sessions. A straightforward therapy, it has remained very popular through the decades and has influenced many other therapeutic modalities.

The second generation challenged the above ideas with solution focused therapy, narrative therapy, and psychoeducation family therapy. Narrative therapy is based around empowering the client while externalizing problems (CitationDoherty & McDaniel, 2010). Psychoeducation family therapy stresses the biological basis of illness and assists families in problem solving and limit setting. This review discusses solution-orientated therapy in further detail.

Solution focused therapy emerged in the mid 1980s and 1990s from the work of couple Steve Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg (CitationLutz & Berg, 2002). Solution focused therapy diverged from the medical model of the therapist trying to solve family problems to the therapist and family working collaboratively on solution-building. In this model, finding the etiology of the problem gives way to goal-driven solutions, as opposed to simply focusing on the problem itself, which leads patients to become disheartened and feel that they are powerless. Instead, this model focuses on five stages: 1) describing the problem, 2) developing goals, 3) finding exceptions, 4) end-of-session feedback, and 5) evaluation of progress. Looking for exceptions is a way to explore problems in a less direct way but also gives insight into how the patient has worked on the problem in the past with positive results, i.e. a child who often hits his sister might be asked about the one time that he wanted to hit his sister this week but did not. In this model, the patient is the expert. Also useful is the ‘miracle question’ – where the therapist asks the client how things would be different if a miracle happened that took away the problem, thus defining goals for the client and family.

The third generation of family therapies includes specialized, evidenced-based models such as multisystemic therapy (discussed below) and multidimensional family therapy, developed for the families of adolescent substance abusers. The latter focuses on affective connections within the family as well as behavioural management.

Multi-systemic family therapy has been used with youthful offenders and values understanding the youth outside of the problem. A therapist might meet the youth at the park and play basketball while learning about his goals and motivations, which may bring up ‘constraining and sustaining elements’, another important step in treatment. Further steps include helping patients envision their desired directions in life and building a community to support the youth and family as a way of meeting immediate and long-range goals. Therapists often make several visits to a family each week as they help the family develop goals and plot their progress by addressing constraining elements (e.g. lack of transportation) and sustaining elements (e.g. a friendly neighbour with a car who is willing to barter for services). As treatment progresses and the natural support network grows, the family needs fewer professional supports as they move closer to their goal (CitationMadsen, 2007).

Conclusion

As the structure of the US family continues to change in the twenty-first century, one wonders how the US society and government will adjust. The USA was founded on ideals of independence and personal freedom, and US society has tended to reflect those ideals, placing a premium on individual rights and initiative derived from within the individual, rather than coming from the family unit, a marked contrast from many other areas of the world (CitationBedford & Hwang, 2003). However, US society is ageing and children of ageing parents are increasingly called upon to provide care (Bianchi, Citation2011). As the world grows more complex with jobs remaining scarce commodities, adolescence is prolonged in favour of additional schooling, increasing the length of time young adults may require parental support (Bianchi, Citation2011). These multi-generational ties create family units with similarities to those in many other societies around the globe but may be foreign to many Americans. At the other end of the spectrum are those without extended families. As the nuclear family degenerates and public support for government programmes in education and financial assistance wane, this population may be especially hard hit. (Teachman et al., 2000). Unfortunately, that may be the very population in the most need of mental health services.

Given that the twentieth century was marked by many societal developments, multiple generations of family therapy were developed to reflect the changing times. The adolescent to adult maturation process in the USA is undergoing change, and with it our way of doing therapy and formulating patients may need to adjust to new developmental benchmarks. The traditional US expectation of parental differentiation has centred around children growing up, leaving their families of origin, and separating from some of the values and ideals of the family unit (CitationKerr & Bowen, 1988). With increasingly common delayed adolescence and prolonged old age, one wonders if these changing demographics will affect how children will differentiate from their families of origin. Additional research into what we once called ‘non-traditional families’ will help to better inform and shape our definition of ‘family’ and how to treat it. Given that many of the family therapies being used were developed in a different time, it stands to reason that our ways of treating the US family will need to continually change as well.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Bedford, O. & Hwang, K.K. (2003). Guilt and shame in Chinese culture: A cross-cultural framework from the perspective of morality and identity. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 33, 127–144.

- Bianchi, S. (2011). Changing families, changing workplaces. The Future of Children, 21, 15–36.

- Cherlin, A. (2010). Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 403–419.

- CIA (2011). The World Factbook. Washington, DC: US Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html.

- Doherty, W.J. & McDaniel, S.H. (2010). Family Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Elliott, D., Young, R. & Dye, J. (2011). Variation in the Formation of Complex Family Households During the Recession. SEHSD Working Paper 2011–32 (pp. 1–20). Minneapolis, MN: National Council on Family Relations.

- Glick, P. (1988). Fifty years of family demography: A record of social change. Journal of Marriage and Family, 50, 861–873.

- Goldstein, J. (1999). The leveling of divorce in the United States. Demography, 36, 409–414.

- Kennedy, S. & Bumpass, L. (2008). Cohabitation and children's living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663–1692.

- Kerr, M.E. & Bowen, M. (1988). Family Evaluation. New York: Norton.

- Lutz, A.B. & Berg, I.K. (2002). Solution-focused family therapy. Encyclopedia of Psychotherapy, Volume 2. New York: Elsevier.

- Madsen, W.C. (2007). Collaborative Therapy with Multi-Stressed Families (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- McLanahan, S. & Beck, A. (2010). Parental relationships in fragile families. The Future of Children, 20, 17–37.

- Taylor, P., Fry, R., Cohn, D., Wang, W., Velasco, G. & Dockterman, D. (2011a). Living Together: The Economics of Cohabitation. Washington, DC: Research Center: Pew Social and Demographic Trends.

- Taylor, P., Kochhar, R., Cohn, D., Passel, J, Velasco, G., Motel, S. & Patten, E. (2011b). Fighting Poverty in a Tough Economy, Americans Move in With Their Relatives. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center: Pew Social and Demographic Trends.

- Teachman, J., Tedrow, L. & Crowder, K. (2000). The changing demography of America's families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1234–1246.

- US Bureau of the Census (1998). Marital status and living arrangements: March, 1998. Current Population Reports (Series P20–514). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- US Bureau of the Census (2012). The 2012 Statistical Abstract: The National Data Book. Population: Households, Families, Group Quarters. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population/households_families_group_quarters.html.