Abstract

Little is known about how psychiatric services respond to service users’ experiences of domestic violence. This qualitative meta-synthesis examined the healthcare experiences and expectations of mental health service users experiencing domestic violence. Twenty-two biomedical, social science, grey literature databases and websites were searched, supplemented by citation tracking and expert recommendations. Qualitative studies which included mental health service users (aged ≥ 16 years) with experiences of domestic violence were eligible for inclusion. Two reviewers independently extracted data from included papers and assessed quality. Findings from primary studies were combined using meta-synthesis techniques. Twelve studies provided data on 140 female and four male mental health service users. Themes were generally consistent across studies. Overarching theoretical constructs included the role of professionals in identifying domestic violence and facilitating disclosures, implementing personalized care and referring appropriately. Mental health services often failed to identify and facilitate disclosures of domestic violence, and to develop responses that prioritized service users’ safety. Mental health services were reported to give little consideration to the role of domestic violence in precipitating or exacerbating mental illness and the dominance of the biomedical model and stigma of mental illness were found to inhibit effective responses. Mental health services often fail to adequately address the violence experienced by mental health service users. This meta-synthesis highlights the need for mental health services to establish appropriate strategies and responses to domestic violence to ensure optimal care of this vulnerable population.

Introduction

Domestic violence is the use of threatening behaviour, violence or abuse towards an adult who is a relative, partner or ex-partner. A major public mental health issue, domestic violence is associated with numerous common mental disorders, perinatal mental disorders, eating disorders, bipolar disorder and psychoses (CitationBundock et al., 2013; CitationHoward et al., 2013; CitationTrevillion et al., 2012a, Citationb).

A recent meta-analysis identified a higher risk of domestic violence among women with depressive disorders (odds ratio (OR) 2.77), anxiety disorders (OR 4.08), and post-traumatic stress disorder (OR 7.34), compared to women without mental disorders (CitationTrevillion et al., 2012b). The review also found an increased risk of experiencing domestic violence among men with mental disorders, although few studies were identified (CitationTrevillion et al., 2012b). Mental health service users report high rates of domestic violence (CitationAlhabib et al., 2010; CitationHoward et al., 2010), with median prevalence estimates for lifetime partner violence of 29.8% among female inpatients, 33% among female outpatients and 31.6% among male patients across mixed psychiatric settings (CitationOram et al., 2013). However, less than a third of cases are detected by mental health professionals, and few service users receive adequate support for domestic violence (CitationAgar & Read, 2002; CitationHoward et al., 2010; CitationMorgan et al., 2010; CitationTrevillion et al., 2012a).

Little is known about the healthcare experiences and expectations of men and women who experience domestic violence and are in contact with mental health services (CitationTrevillion et al., 2012a). This review therefore seeks to identify how mental health service users want mental health services to respond to disclosures of domestic violence victimization. Qualitative meta-synthesis techniques were used to understand and explain the narratives, using the nuances, assumptions and textured milieu of varying accounts to be revealed, described and explained in ways that bring new theoretical insights (CitationWalsh & Downe, 2005).

Methods

Data sources

Eighteen biomedical and social science databases (including MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO) (see the supplementary material for a full list of search terms and databases used) and four grey literature websites and databases (Department of Health; The King's Fund; Open Grey and Social Care Institute for Excellence) were searched from their respective start dates to 31 March 2011. Additional searches of MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and the grey literature websites and databases were conducted for the period 1 April 2011 to 31 January 2014. These sources were used for the updated search as all of the previously included articles were identified exclusively from these sources. Database and website searches were supplemented by hand searches of key journals (Journal of Family Violence; Journal of Interpersonal Violence; Trauma, Violence and Abuse, and Archives of Women's Mental Health), citation tracking and expert recommendations. Search terms for domestic violence were adapted from published Cochrane protocols (CitationDalsbo & Johme, 2006; CitationRamsay et al., 2009); search terms for mental health services were adapted from NICE guidelines (CitationNICE, 2008). Specific terms for qualitative research designs were not included in the search strategy, as the coding of papers as qualitative is not found to be reliable (CitationAtkins et al., 2008).

Selection criteria

Three reviewers (S.O., K.T. and R.B.) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. The inclusion criteria were (1) studies that used qualitative research designs, (2) studies that included mental health service users (aged ≥ 16 years) who had experienced domestic violence, (3) studies reporting on mental health service users’ experiences and expectations of mental health services in relation to domestic violence, and (4) studies published in journal articles, thesis/dissertations or reports. Studies reported in book chapters, conference papers, editorials, letters or general comment papers were excluded. For the purposes of this review, domestic violence is defined as ‘any incident of threatening behaviour, violence or abuse (psychological, physical, sexual, financial or emotional) between adults who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality’ (CitationHome Office, 2005, p. 7).

Following abstract screening, three reviewers (B.H., S.O. and K.T.) assessed the full texts of potentially eligible studies. Uncertainty or disagreement was resolved by consensus decision. If studies collected relevant data but did not report it, data were requested from the authors. Details of the excluded papers and reasons for exclusion are available upon request.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

One reviewer (B.H.) extracted data from each study onto a standardized form created specifically for this review. Data were extracted on mental health service users’ experiences and expectations of their encounters with mental health services (first-order constructs) and researchers’ interpretations and explanations (second-order constructs). Two reviewers (S.O. and K.T.) cross-checked all data extracted by the first reviewer (B.H.).

In the absence of a gold-standard appraisal tool (CitationDixon-Woods et al., 2006), the methodological quality of studies was independently assessed by three reviewers (B.H. and S.O./K.T.) using criteria adapted from pre-developed checklists (CitationLong & Godfrey, 2004; CitationPublic Health Resource Unit, 2006; CitationSpencer et al., 2003; CitationWalsh & Downe, 2006). Quality appraisal questions included (1) the theoretical frameworks guiding study designs, (2) methods of analysis and interpretation of data, (3) researcher's reflexivity during data collection and analysis, and (4) consideration of ethical issues (the appraisal checklist is available from the authors on request). Reviewers compared scores and resolved disagreements before calculating a total score (out of a possible score of 86). All quality appraisal forms were sent to authors for verification (CitationAtkins et al., 2008).

Analysis

Meta-synthesis techniques aim to amalgamate qualitative research findings and develop new theoretical insights (CitationBarroso & Powell-Cope, 2000). At present, there are no standardized methods for synthesizing qualitative research and there is variation in underlying theoretical assumptions (CitationCentre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2008). Our analytical methods are based on meta-ethnography (CitationNoblit & Hare, 1988), one of the most widely used techniques for the synthesis of health research (CitationBondas & Hall, 2007; CitationCampbell et al., 2011). This method treats the interpretations and explanations of primary studies as ‘data’, and this ‘data’ is compared and contrasted by reviewers before being translated to produce new insights (CitationNoblit & Hare, 1988). Within this technique the views of study participants are ‘first-order constructs’, the explanations of study authors are ‘second-order constructs’, and the relationship identified by reviewers between findings from the different primary studies are ‘third-order constructs’ (CitationNoblit & Hare, 1988).

Our synthesis began with the identification and synthesis of first- and second-order constructs that were similar across studies (‘reciprocal translation’ (CitationNoblit & Hare, 1988)). This was followed by a process of repeated reading and discussion to articulate third-order constructs, which denote our synthesis of findings that were consistently supported across studies (CitationFeder et al., 2006). We then sought to identify study constructs that were seemingly contradictory (‘refutational translation’ (CitationNoblit & Hare, 1988)), both within the same study (i.e. intra-study contradiction) and between studies (i.e. inter-study contradiction). We sought to explain these apparent contradictions by examining factors within studies, and where there was a plausible explanation for a contradiction it was expressed as a third-order construct. We noted where contradictions could not be resolved. Third-order constructs were organised by pathways of care.

As there is currently no consensus regarding the exclusion of studies based on reasons of quality (CitationDaly et al., 2007; CitationDixon-Woods et al., 2006; CitationSandelowski, 2006), all studies were included in the analysis. A sensitivity analysis of first-order constructs was, however, undertaken to assess the possible impact of study quality on the review findings (CitationBarnett-Page & Thomas, 2009). We examined the distribution of quality scores across studies on which the constructs were based. Studies scoring ≥ 50% of the total score for quality appraisal were categorized as higher quality papers and those scoring < 50% were categorized as lower quality papers. We also sought to assess whether the explanations of the study authors (second-order constructs) were supported by the views of study participants (first-order constructs).

In order to increase the transparency of how constructs were conceptualized and compared, we tabulated all first-, second- and third-order constructs. The construct names in each of the tables seek to encompass all relevant theoretical constructs across primary studies and are ordered according to pathways of care. It is noted where first-order constructs were not identified by higher quality papers, and where second-order constructs were not supported by first-order constructs.

Results

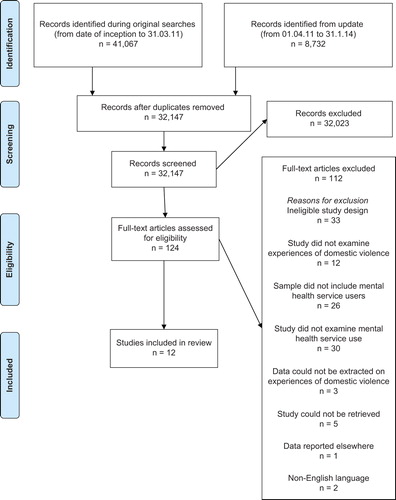

The study selection process is presented in . A total of 124 abstracts were identified as potentially eligible for inclusion during title and abstract screening. Following full text screening and contact with authors, 12 studies were included in the review (see ). Six studies were reported in peer-reviewed journals, four in published reports and two in theses or dissertations. In seven studies, authors did not state the theoretical frameworks underpinning the research, four broadly followed a feminist perspective, and one was informed by both a constructionist and realist paradigm.

Table 1. Characteristics and quality scores of included studies.

Studies reported data from 140 female and four male mental health service users who had experienced domestic violence. Types of mental health setting included statutory inpatient (n = 2) and outpatient (n = 4) services, community mental health services (n = 7) and non-statutory outpatient and community mental health services (n = 3); three studies did not specify the type of mental health service setting. Four studies were conducted in Australia, five in the UK, one in the Netherlands, one in New Zealand and one in the Republic of Ireland. Ten studies included female only samples (CitationBarron, 2004; CitationBates et al., 2001; CitationBradbury-Jones et al., 2011; CitationHager, 2001; CitationLaing et al., 2010; CitationProsman et al., 2014; CitationRuddle & O’Connor, 1992; CitationSpangaro et al., 2011; CitationTower, 2008; CitationWomen's National Commission, 2010), and two studies included a mixed sample of male and female mental health service users (CitationRose et al., 2011; CitationTrevillion et al., 2012a). Further details about the studies, including participant characteristics and quality appraisal scores are summarized in .

First-order constructs

A total of 20 first-order constructs (i.e. the reported views of study participants) were identified (see ). The most commonly identified constructs were the importance of professional identification and acknowledgement of abuse, the limitations of the biomedical model of mental illness, and the need for professionals to prioritize service users’ safety. A sensitivity analysis found that the constructs of ‘dissatisfaction with counselling services’ and ‘safety of mental health inpatient services’ were not identified by higher quality papers.

Table 2. First-order constructs.

Failure to identify abuse

Mental health service users described a fear of disclosure, and that mental health professionals often failed to identify their experiences of domestic violence. For some this was related to professionals’ difficulties in identifying their experiences as abusive, or language and cultural barriers. Overall, service users were in favour of direct enquiry about domestic violence, and some recommended that staff receive training to improve their skills of enquiry; variations in this view are explored below (see the section on contradictory findings).

Lack of acknowledgement

Mental health service users described how mental health professionals largely failed to acknowledge or validate their disclosures of domestic violence. Stigma and blame appeared to be related to this, and some service users felt that the label of mental illness meant that some mental health professionals did not take their disclosures seriously. This lack of acknowledgement was felt to be compounded by limited opportunities for service users to explore issues of abuse during consultations. Service users spoke of the need for mental health professionals to acknowledge and respond in a non-judgemental and compassionate manner to disclosures of abuse.

Limitations of the biomedical model

Many service users described how mental health professionals focused solely on diagnosing and treating psychiatric symptoms and did not explore the underlying causes of their illness. Service users explained that this focus often prevented them from recognizing the extent of abuse, and the label of mental illness had the effect of minimizing their experiences of abuse. The dominance of the biomedical model was felt to contribute to mental health professionals’ failure to identify and acknowledge abuse.

Risk of harm

Mental health service users valued responses that addressed their safety concerns. Some reported that mental health professionals’ responses to the violence placed them at risk of further harm. For example, one woman felt that a psychiatrist compromised her safety by discussing the abuse in front of her partner. Another described how her treating clinician inappropriately prescribed marital therapy, which prolonged her experience of abuse and allowed her abuser to act out the dynamics of coercive control within therapeutic sessions.

Referral

Mental health service users spoke of the importance of referrals that connected them with other people who had experienced abuse. They called for improved communication and coordinated service delivery between mental health and domestic violence services.

Second-order constructs

A total of 18 second-order constructs (i.e. the interpretations and explanations of study authors) were identified (see ). The most commonly identified themes related to facilitating disclosures and identifying abuse, and moving beyond the biomedical model of mental illness. The construct ‘role of third sector‘, describing partnership with third sector services that support people experiencing domestic violence, was not present in the reported views of study participants (first-order constructs).

Table 3. Second-order constructs.

Facilitating disclosures

Authors highlighted the importance of creating a supportive environment for disclosures of abuse, and emphasized the value of verbal and non-verbal cues in establishing patient–provider trust. Several authors highlighted that mental health service users would not disclose domestic violence without being asked directly by providers, and therefore recommended that mental health services implement routine enquiry about domestic violence. Authors cautioned that service users’ reluctance to disclose domestic violence was often related to fears about the potential consequences of disclosure (e.g. social services involvement, further violence, and disruption to family life), and recommended that mental health professionals discuss the limits of confidentiality and potential implications of disclosures with service users.

Identifying abuse

Authors suggested that the identification of domestic violence by mental health professionals was hindered by a lack of time, fear of offending service users, and fear of not being able to respond appropriately to disclosures. Consequently, they recommended that mental health professionals receive regular training to improve their confidence and cross-cultural communication in recognizing and responding to abuse, and establish joint outreach visits and inter-agency working partnerships with the domestic violence sector. Authors also recommended that when abuse is suspected, services should provide information on what support is available to mental health service users.

Psychosocial model of mental illness

Authors recommended that, alongside diagnosing and treating psychiatric symptoms, mental health professionals should explore the underlying causes for mental illness – including experiences of domestic violence. They suggested that the potential consequences of failing to identify the psychosocial impact of abuse included the internalization of distress; the reinforcement of feelings of self-blame; prolonged contact with mental health services, and the potential for service users to remain in abusive relationships.

Referral

Authors underlined the importance for mental health professionals to be aware of domestic violence services and to signpost service users to various support agencies. They called for improved communication between mental health and domestic violence services and stressed the need for partnership working between the two sectors.

Contradictory constructs

Our analysis identified three apparent contradictions (see ). These constructs also present any second-order constructs developed by the study authors about the contradictions, and any third-order constructs that we have developed to resolve the apparent contradictions. Two of the contradictions are intra- and inter-study contradictions (contradictions 1 and 2).

Table 4. Intra- and inter-study contradictions.

Contradiction 1 regards the acceptability of enquiry by mental health professionals about domestic violence: some service users found it unacceptable to be asked. The second-order constructs of the authors suggests that service users’ feelings of safety may explain variations in their views of acceptability. Service users who did not feel safe in relation to experiencing further violence, shame, and loss of control over their situation found routine enquiry unacceptable. Second-order constructs resolve this contradiction by highlighting the need for mental health professionals to recognize and address service users’ feelings of shame, sense of autonomy, and physical safety when enquiring about domestic violence.

Contradiction 2 concerns service users’ reports of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the responses of mental health professionals. Service users reported satisfaction with responses that provided both practical and emotional support, which challenged the acceptability of abusers’ behaviour and which gave information about the dynamics of abuse. Service users reported dissatisfaction with responses that did not meet their practical needs and which concentrated on changing their reactions to abuse without addressing the role of the abuser. The second-order constructs resolve this contradiction by identifying the need for mental health professionals to create opportunities for service users to discuss abuse, to develop responses that challenge the acceptability of abusers’ behaviours and to establish care plans that are individually tailored to the needs of service users.

Contradiction 3, an intra-study contradiction, concerns the appropriateness or inappropriateness of marital therapy in the context of domestic violence. Several service users felt that marital therapy was unhelpful, failed to reduce abuse and resulted in collusion between the therapist and abuser, yet a few described that it was successful in stopping the abuse. This contradiction was not resolved by second-order constructs. We suggest that the appropriateness of marital therapy may be related to the type of abuse experienced by service users. Marital therapy may be beneficial for relationships in which acts of violence occur infrequently and are not associated with a pattern of coercion, and where both partners want to end the violence.

Third-order constructs

Third-order constructs were identified during the synthesis of first- and second-order constructs (see ). These third-order constructs represent our interpretations of the desired characteristics of service providers, as articulated by the service users (first-order constructs) and authors (second-order constructs) of studies, and are presented with accompanying recommendations.

Table 5. Third-order constructs shown as recommendations to mental health service providers.

Before disclosure or questioning

Mental health professionals should be proactive in looking for signs and signposting to appropriate support services. We recommend that mental health professionals undertake training to equip them with skills to assist service users in recognizing and responding to domestic violence, and to understand the relationship between violence and mental illness. We recommend that mental health professionals create a supportive and confidential environment in which to facilitate opportunities for disclosure, through direct enquiry, and to address mental health service users’ concerns and needs.

Immediate responses following disclosure

Mental health professionals should provide service users with sufficient information to make informed decisions about the implications of disclosure and their options in addressing abuse (e.g. outlining the limits of confidentiality and providing information on support services). We recommend that mental health professionals provide validating and non-judgemental responses which address issues of safety and available support options, ensuring service users’ autonomy in subsequent decisions.

Ongoing responses

Mental health professionals should provide continued support for service users which include iterative discussions about their needs and an explanation of the rationale for clinical actions. We recommend that professionals provide continuity of care and individually tailored support.

Discussion

Key findings

This is the first review to examine the experiences and expectations of mental health service users who have experienced domestic violence. Our findings indicate that mental health services often fail to identify and facilitate disclosures of domestic violence, and to develop responses that prioritize service users’ safety. Mental health services were reported to give little consideration to the role of domestic violence in precipitating or exacerbating mental illness and the dominance of the biomedical model and stigma of mental illness was found to inhibit effective responses.

Identification of domestic violence

We found that mental health service users report additional barriers to disclosure of domestic violence due to the stigma associated with mental illness. In addition, findings suggest that mental health professionals may question the credibility of service users’ disclosure of abuse in light of their mental illness. This is despite evidence that service users are more likely to under-report than over-report experiences of abuse (CitationGoodman et al., 1999). The dominance of the biomedical model was also found to result in a failure of mental health professionals to identify and acknowledge domestic violence, and prevented some service users from recognizing the extent of abuse. The overriding focus on diagnosing and treating symptoms also resulted in service users feeling that professionals overlooked the impact of abuse on their mental health. Similar findings have been identified in other research with mental health service users and professionals (CitationTrevillion et al., 2012a) and highlight the need for professionals to have greater awareness of psychosocial models of care (CitationDepartment of Health, 2010).

The high prevalence of domestic violence reported by mental health service users (CitationHoward et al., 2010; CitationOram et al., 2013) underlines the importance of professionals being able to identify and respond safely and appropriately to disclosures. Several recommendations emerge from this review regarding how to improve responses to domestic violence within mental health settings, including the provision of information about domestic violence, skills training to improve professional competencies in recognizing and responding to abuse, and signposting to appropriate support services. Some of these strategies correspond with recommendations made elsewhere for professionals working in primary and secondary healthcare settings (CitationBacchus et al., 2008; CitationChang et al., 2011; CitationFeder et al., 2006, Citation2009; CitationNyame et al., 2013). However, a number of studies included in this review also recommend the implementation of routine enquiry for domestic violence in mental health services, which aligns with current national (CitationNICE, 2014) and international guidelines (CitationWHO, 2013). Although detection rates may improve following the implementation of routine enquiry (CitationHoward et al., 2010), there is insufficient evidence on whether routine enquiry leads to improved mortality or morbidity outcomes among abused women (CitationFeder et al., 2009; CitationMacMillan et al., 2006). Furthermore, research in other healthcare settings suggests that routine enquiry can have adverse consequences if professionals are not trained to enquire safely about domestic violence (CitationBacchus et al., 2010). Professionals working in mental health settings, therefore, require training on how to appropriately identify and respond to domestic violence prior to the implementation of routine enquiry. Research suggests mental health services need to establish specific domestic violence policies and implement training programmes on sensitive abuse enquiry (CitationChang et al., 2011; CitationHolly et al., 2012; CitationNyame et al., 2013) in order to facilitate changes in clinical practice.

Responses to domestic violence

Our review found that current responses to domestic violence may put mental health service users at further risk of harm and contribute to worsening mental health symptoms. This is particularly apparent in instances when professionals discuss the abuse in front of violent partners and/or prescribe marital therapy. Such responses can increase service users’ risk of abuse, reinforce feelings of self-blame, and allow abusers the opportunity to exert further power over their partner within the therapeutic environment. These findings underline the need for clinicians to conduct comprehensive assessments of the context, motivations and meanings surrounding abuse prior to the formulation of treatment plans. Indeed, the needs of service users who experience infrequent violence which is not associated with a general pattern of control are likely to be considerably different to the needs of service users who experience severe and frequent violence with high levels of coercion and control (CitationJohnson, 1995; CitationStark, 2006). Consequently, marital therapy is not deemed appropriate for relationships characterized by frequent and severe levels of violence (CitationBograd & Mederos, 1999).

The above findings also highlight the importance for mental health professionals in documenting disclosures of domestic violence. These practices can support professionals in acknowledging and validating disclosures, assessing risk of harm and promoting clear care referral pathways. Good practice recommendations for documentation of abuse include making accurate notes, conducting risk assessments (particularly with regard to immediate safety of service users and their children), safety planning, and discussing options in addressing the abuse with service users (CitationTrevillion et al, 2010). One author of a primary study in our review recommended the use of ‘appropriate guidelines’ when working with perpetrators, in order to ensure that their actions do not compromise service users safety (CitationBates et al., 2001). However, such guidelines are not widely available and there is limited evidence about mental healthcare for perpetrators of domestic violence with mental disorders.

Finally, this review highlights the difficulties that service users experience with regard to accessing mainstream domestic violence services, due to the stigma associated with mental illness. Interestingly, a recent survey of 58 refuges in London, England found that several refuges refused space to women experiencing certain types of mental health problems (e.g. schizophrenia) and/or using substances such as methadone (CitationHarvey et al., 2014). Similarly, a New Zealand survey of 39 women's refuges found that over a 6-month period 179 women were denied access because of mental health and/or substance abuse problems (CitationHager, 2006). These findings suggest therefore that people with a mental illness who experience domestic violence may encounter additional barriers with regard to obtaining access to and contact with domestic violence services (CitationTrevillion et al., 2012a). International guidance and research recommendations advocate for the development of clear care referral pathways (CitationFeder et al., 2011; CitationNICE, 2014; CitationNyame et al., 2013; CitationWHO, 2013) and the establishment of local service level agreements with specialist support services (CitationHarvey et al., 2014).

Limitations

Several studies that would have otherwise been eligible for inclusion did not measure the type of violence experienced by service users and could not be included in our synthesis, with a consequent loss of primary data. A number of other studies included participants who had suffered domestic violence but reported on the healthcare experiences of participants across a range of clinical settings, and did not disaggregate the types of services accessed. In the majority of studies mental health service users formed a sub-sample of the study population, and therefore the authors’ conclusions frequently did not make specific reference to mental health services. Only two of the ten studies in this review included male service users, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about the experiences and expectations of abused men in contact with mental health services.

The appropriateness of amalgamating qualitative research findings that employ different theoretical assumptions and methodologies has been questioned, and the process of qualitative synthesis criticized as reductionist (CitationSandelowski, 2006). However, our review and other recent reviews suggest that it is possible to successfully synthesize research from different paradigms (CitationGarside, 2008). Indeed, some commentators argue that combining data from multiple theoretical traditions can strengthen the quality of reviews (CitationFinfgeld-Connett, 2008). We suggest that meta-synthesis is the most transparent method of comparing and synthesizing primary studies (CitationBarnett-Page & Thomas, 2009) and enables qualitative findings to be translated into practical recommendations for mental health professionals and services.

Due to a lack of consensus regarding the exclusion of studies on grounds of quality, we included all eligible studies in our analysis. It is important to note that a small number of first-order constructs were not identified by high-quality papers, and these should be interpreted with caution.

Future research priorities

Few studies focused specifically on the experiences of abused mental health service users, and in particular abused male service users. Therefore, further research is needed on what is and is not helpful in relation to responses of mental health services to domestic violence.

Conclusion

The interrelatedness of mental health and domestic violence and the specific needs of mental health service users who are abused are inadequately addressed by mental health services. Mental health professionals need specific training and education on domestic violence to ensure the safe and optimal care of this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the authors and experts in this area who responded so helpfully to our request for data. We also gratefully acknowledge Jack Ogden for his assistance with the search update.

Declaration of interest: This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0108-10084 to K.T., S.O., G.F. and L.H.) and an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-R3-12-011 to L.H.). B.H. is supported by the Brighton and Sussex Medical School, UK. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. L.H. and G.F. were members of the WHO Guideline Development Group on Violence Against Women and NICE/SCIE Guideline Development Group on Preventing and Reducing Domestic Violence. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Agar, K., & Read, J. (2002). What happens when people disclose sexual or physical abuse to staff at a community mental health centre? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 11, 70–79.

- Alhabib, S., Nur, U., & Jones, R. (2010). Domestic violence against women: Systematic review of prevalence studies. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 369–382.

- Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Engel, M., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2008). Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 21.

- Bacchus, L., Mezey, G., & Bewley, S. (2008). Women's perceptions and experiences of routine enquiry for domestic violence in a maternity service. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 109, 9–16.

- Bacchus, L.J., Bewley, S., Torres Vitolas, C., Aston, G., Jordan, P., & Murray, S.F. (2010). Evaluation of a domestic violence intervention in the maternity and sexual health services of a UK hospital. Reproductive Health Matters, 18, 147–157.

- Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 59.

- Barron, J. (2004). Struggle to Survive: Challenges for Delivering Services on Mental Health, Substance Misuse and Domestic Violence. Bristol: Women's Aid.

- Barroso, J., & Powell-Cope, G.M. (2000). Metasynthesis of qualitative research on living with HIV infection. Qualitative Health Research, 10(3), 340–353.

- Bates, L., Hancock, L., & Peterkin, D. (2001). ‘A little encouragement’: Health services and domestic violence. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 14, 49–56.

- Bograd, M., & Mederos, F. (1999). Battering and couples therapy: Universal screening and selection of treatment modality. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 25, 291–312.

- Bondas, T., & Hall, O.C.E. (2007). A decade of metasynthesis research in health sciences: A meta-method study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 2, 101–113.

- Bradbury-Jones, C., Duncan, F., Kroll, T., Moy, M., & Taylor, J. (2011). Improving the health care of women living with domestic abuse. Nursing Standard, 25, 35–40.

- Bundock, L., Howard, L.M., Trevillion, K., Malcolm, E., Feder, G., & Oram, S. (2013). Prevalence and risk of experiences of intimate partner violence among people with eating disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47, 1134–1142.

- Campbell, R., Pound, P., Morgan, M., Daker-White, G., Britten, N., Pill, R., … Donovan, J. (2011). Evaluating meta-ethnography: Systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment, 15(43), 1–164.

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2008). Systematic Reviews: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. York: University of York.

- Chang, J.C., Cluss, P.A., Burke, J.G., Hawker, L., Dado, D., Goldstrohm, S., & Scholle, S.H. (2011). Partner violence screening in mental health. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33, 58–65. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.11.009

- Dalsbø, T.K., Johme, T., Smedslund, G., Steiro, A., & Winsvold, A. (2006). Cognitive behavioural therapy for men who physically abuse their female partner (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD006048. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006048.

- Daly, A., Willis, K., Small, R., Green, J., Welch, N., Kealy, M., & Hughes, E. (2007). Hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, 43–49.

- Department of Health. (2010). Responding to Violence Against Women. Report from the Taskforce on the Health Aspects of Violence Against Women and Children. London: Department of Health.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Bonas, S., Booth, A., Jones, D.R., Miller, T., Sutton, A.J., … Young, B. (2006). How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qualitative Research, 6, 27–44.

- Feder, G., Agnew-Davies, R., Baird, K., Dunne, D., Eldridge, S., Griffiths, C., … Sharp, C. (2011). Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence with a primary care training and support programme: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 11, 1–8.

- Feder, G., Hutson, M., Ramsay, J., & Taket, A.R. (2006). Women exposed to intimate partner violence. Expectations and experiences when they encounter health-care professionals: A meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166, 22–37.

- Feder, G., Ramsay, J., Dunne, D., Rose, M., Arsene, C., Norman, R., … Taket, A. (2009). How far does screening women for domestic (partner) violence in different health-care settings meet criteria for a screening programme? Systematic reviews of nine UK, National Screening Committee critieria. Health Technology Assessment, 13(16), iii–iv, xi–xiii, 1–113, 136–347.

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2008). Meta-synthesis of caring in nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 196–204.

- Garside, R. (2008). A comparison of methods for the systematic review of qualitative research: Two examples using meta-ethnography and meta-study. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) University of Exeter and Plymouth, Exeter.

- Goodman, L.A., Thompson, K.M., Weinfurt, K., Corl, S., Acker, P., Mueser, K.T., & Rosenberg, S.D. (1999). Reliability of reports of violent victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among men and women with serious mental illness. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12, 587–599.

- Hager, D. (2006). Domestic violence and mental illness/substance abuse. A survey of 39 refuges. Auckland, NZ: Homeworks Trust (pp. 1–13).

- Hager, D.M. (2001). He drove me mad. An investigation into the relationship between domestic violence and mental illness. Auckland, NZ: University of Auckland,

- Harvey, S., Mandair, S., & Holly, J. (2014). Case by Case: Refuge Provision in London for Survivors of Domestic Violence Who Use Alcohol and Other Drugs or Have Mental Health Problems. London: Solace Women's Aid.

- Holly, J., Scalabrino, R., & Woodward, B. (2012). Promising Practices: Mental Health Trust Responses to Domestic Violence. London: AVA.

- Home Office. (2005). Domestic Violence: A National Report (p. 7). London: Home Office.

- Howard, L.M., Oram, S., Galley, H., Trevillion, K., & Feder, G. (2013). Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med, 10, e1001452. doi:1001410.1001371/journal.pmed.1001452

- Howard, L.M., Trevillion, K., Khalifeh, H., Woodall, A., Agnew-Davies, R., & Feder, G. (2010). Domestic violence and severe psychiatric disorders: prevalence and interventions. Psychological Medicine, 40, 881–893.

- Johnson, M.P. (1995). Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57, 283–294.

- Laing, L., Toivonen, C., Irwin, J., & Napier, L. (2010). ‘They Never Asked Me Anything About That’: The Stories of Women who Experience Domestic Violence and Mental Health Concerns/Illness. Sydney: Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Sydney.

- Long, A.F., & Godfrey, M. (2004). An evaluation tool to assess the quality of qualitative research studies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 7, 181–196.

- MacMillan, L.H., Wathen, C.N., Jamieson, E., Boyle, M., McNutt, A.L., Worster, A., … Webb, M. (2006). Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: A randomized trial. JAMA, 296, 530–536.

- Morgan, J.F., Zolese, G., McNulty, J., & Gebhardt, S. (2010). Domestic violence among female psychiatric patients: Cross-sectional survey. Psychiatrist, 34, 461–464.

- NICE. (2014). Domestic Violence and Abuse – How Services Can Respond Effectively. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- NICE. (2008). The Guidelines Manual. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- Noblit, G.W., & Hare, R.D. (1988). Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Nyame, S., Howard, L.M., Feder, G., & Trevillion, K. (2013). A survey of mental health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and preparedness to respond to domestic violence. Journal of Mental Health, 26, 536–543.

- Oram, S., Trevillion, K., Feder, G., & Howard, L.M. (2013). Prevalence of experiences of domestic violence among psychiatric patients: Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 202, 94–99.

- Prosman, G.J., Lo Fo Wong, S.H., & Lagro Janssen, A.L. (2014). Why abused women do not seek professional help: A qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28, 3–11.

- Public Health Resource Unit. (2006). 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Oxford: Public Health Resource Unit, England.

- Ramsay, J., Carter, Y., Davidson, L., Dunne, D., Eldridge, S., Feder, G., … Warburton, A. (2009). Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, CD005043. doi: 005010.001002/14651858.CD14005043.pub14651852.

- Rose, D., Trevillion, K., Woodall, A., Morgan, C., Feder, G., & Howard, L. (2011). Barriers and facilitators of disclosures of domestic violence by mental health service users: Qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(3), 189–194.

- Ruddle, H., & O’Connor, J. (1992). ‘Breaking the Silence’: Violence in the Home: The Women's Perspective. Limerick: Mid-Western Health Board, ADAPT Refuge.

- Sandelowski, M. (2006). ‘Meta-jeopardy’: The crisis of representation in qualitative metasynthesis. Nursing Outlook, 54, 10–16.

- Spangaro, J.M., Zwi, A.B., & Poulos, R.G. (2011). ‘Persist. persist.’: A qualitative study of women's decisions to disclose and their perceptions of the impact of routine screening for intimate partner violence. Psychology of Violence, 1, 150–162. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0023136

- Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2003). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. London: Cabinet Office.

- Stark, E. (2006). Commentary on Johnson's ‘Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence’. Violence Against Women, 12(11), 1019–1025.

- Tower, M. (2008). Health and Healthcare for Women Affected By Domestic Violence. Stories of Disruption, Fragmentation and Re-construction. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Griffith University, Queensland.

- Trevillion, K., Agnew-Davies, R., & Howard, L.M. (2010). Domestic violence: responding to the needs of patients. Nursing Standard, 25, 48–56.

- Trevillion, K., Howard, L.M., Morgan, C., Feder, G., Woodall, A., & Rose, D. (2012a). The response of mental health services to domestic violence: A qualitative study of service users’ and professionals’ experiences. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 18, 326–336. doi: 10.1177/1078390312459747

- Trevillion, K., Oram, S., Feder, G., & Howard, L.M. (2012b). Experiences of domestic violence and mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. doi: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051740

- Walsh, D., & Downe, S. (2005). Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 50, 204–211.

- Walsh, D., & Downe, S. (2006). Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery, 22, 108–119.

- Women's National Commission. (2010). A Bitter Pill to Swallow: Report from WNC Focus Groups to inform the Department of Health Taskforce on the Health Aspects of Violence Against Women and Girls (pp. 1–135). London: Department of Health.

- WHO. (2013). Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization.