Abstract

Background: Over the past six decades, the concept of patient-centred care (PCC) has been discussed in health research, policy and practice. However, research on PCC from a patients’ perspective is sparse and particularly absent in outpatient psychiatric services.

Aim: to gain insight into what patients with bipolar disorder and ADHD consider “good care” and what this implies for the conceptualisation of PCC.

Method: A literature review on the different conceptualisations of PCC was complemented with qualitative explorative research on the experiences and needs of adults with ADHD and with bipolar disorder with mental healthcare in the Netherlands using focus group discussions and interviews.

Results: The elements addressed in literature are clustered into four dimensions: “patient”, “health professional”, “patient–professional interaction” and “healthcare organisation”. What is considered “good care” by patients coincided with the four dimensions of PCC found in literature and provided refinement of, and preferred emphasis within, the dimensions of PCC.

Conclusions: This study shows the value of including patients’ perspectives in the conceptualisation of PCC, adding elements, such as “professionals listen without judgment”, “professionals (re)act on the fluctuating course of the disorder and changing needs of patients” and “patients are seen as persons with positive sides and strengths”.

Introduction

The concept of patient-centred care (PCC) has been applied to healthcare policy and healthcare delivery for more than 60 years (Hudon et al., Citation2011). In 2001, the US Institute of Medicine added PCC to its objectives in recognition of the role of PCC in improving quality of care (Institute of Medicine, Citation2001). Since then, PCC has become the focus of recent healthcare reform in many Western healthcare systems (Robinson et al., Citation2008; Scambler & Asimakopoulou, Citation2014). Reasons for the popularity of PCC are twofold. First, it is grounded in the moral and ethical belief that it is the right thing to do regardless of its influence on health outcomes (Duggan et al., Citation2006). According to medical ethics, the autonomy of patients should be respected and they should be treated with respect and dignity (Epstein et al., Citation2010). Second, the delivery of PCC is associated with improved health outcomes, satisfaction with care and reduced healthcare costs (Epstein, Citation2000; Greene et al., Citation2012; Hudon et al., Citation2011; Mills et al., Citation2014; Robinson et al., Citation2008; Storm & Edwards, Citation2013).

Since its inception in the 1950s, various efforts have been made to define and conceptualise PCC. Initially, PCC was referred to as “individualised care based on patient-specific information” (Hobbs, Citation2009, p. 53) because each patient “has to be understood as a unique human-being” (Balint, 1969, quoted in Saha et al., Citation2008, p. 1). A definition of PCC that is commonly used is the one formulated by the US National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine, IOM) “a partnership among practitioners, patients and their families (when appropriate) to ensure that decisions respect patients' wants, needs and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care” in every stage of healthcare from entry to discharge (Institute of Medicine, Citation2001, p. 7). Other more instrumental conceptualisations recognise PCC as a measure of the quality of healthcare provided by healthcare organisations (Robinson et al., Citation2008). Although PCC has a long history of political and academic attention, it is still being criticised for its unclear conceptualisation. According to Stewart (Citation2001, p. 444–5), “PCC is better understood for what it is not” and definitions are “often oversimplified” and “fail to capture the indivisible whole of a healing relationship”.

In this article, we are particularly interested in PCC in the context of mental health. In this context, PCC is mostly described within specific subfields, for example dementia (Clissett et al., Citation2013; Stokes, Citation2005), forensic psychiatry (Encinares & Golea, Citation2005; Livingston et al., Citation2012) or psychiatric education (McGinty et al., Citation2012; Robinson et al., Citation2010). Most literature concerns inpatient psychiatry which poses a distinct set of problems as compared to outpatient services, such as hospitalisation, isolation and coercion (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2014; Geller, Citation2012; Storm & Edwards, Citation2013). As the majority of the Dutch patients are treated in an outpatient clinic (Trimbos Instituut, Citation2015), it is important to understand the conceptualisation and implications for practice of PCC in this area as well.

However, research that takes a patient’s perspective on PCC is sparse. This is striking as the core idea of PCC is that the patient should be placed at the centre of healthcare provision (Robinson et al., Citation2008). To the best of our knowledge, only two qualitative articles have been published about the perspectives of mental health patients on PCC (Corring & Cook, Citation1999; Williams et al., Citation1999). Although articles have been published on perspectives of mental health patients on good care, this is not yet linked to PCC (Johansson & Eklund, Citation2003). In addition, no articles have been published that explore PCC from the perspective of patients treated in outpatient psychiatric services. We argue that patients’ stories are needed to give meaning to the concept of PCC discussed in the literature and to see if this conceptualisation matches the perspectives and experiences of psychiatric patients. Thus, the aim of this study is to gain insight into what patients with bipolar disorder and ADHD consider “good care” and what this implies for the conceptualisation of PCC.

Methods

A three-step approach was used. First, a narrative literature review with systematic search was conducted to synthesise a model that integrates recent conceptualisations of PCC. Second, qualitative explorative research was conducted on the experiences and needs of adults with ADHD and adults with bipolar disorder with respect to mental healthcare in the Netherlands. Finally, the review findings and the patient perspectives were compared.

Literature review

Search strategy

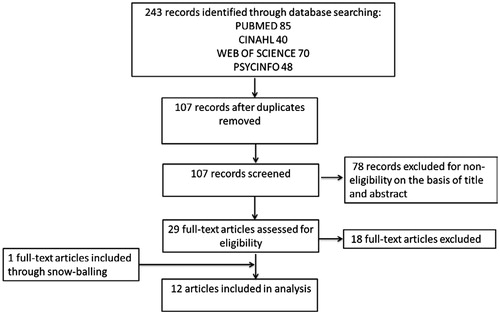

Empirical research on PCC and its implementation in specific healthcare settings is extensive. However, relatively few articles focus on theoretical or conceptual underpinnings of the concept. As the latter were the focus of our interest, we chose to only include review articles and theoretical articles that used literature as their prime data source. Two researchers (EM and BR) separately performed searches and search strings and results were discussed by the entire research team in order to develop the final search string. The search for relevant literature was performed in four databases: PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Web of Science. The keywords used were patient/person/user/client centred/oriented/focused care OR patient/person/user/client centeredness OR tailor made care OR individualised care, in the title, in both US and UK spelling, AND dimension OR concept OR principle in the abstract, AND literature OR review, in the abstract.

Conflicting ideas on what to include or exclude were resolved through discussion by the research team. Articles were included if they were (1) about the theoretical conceptualisation of PCC, and (2) were literature reviews. Articles were excluded when (1) they were not written in English or (2) they were about PCC in a specific context (e.g. specific disease). Search results from the four databases were imported in endnote and the duplicates were removed resulting in 107 original articles. Seventy-eight articles were excluded after screening for eligibility based on the title and abstract. Eighteen articles were excluded after reading the full text, resulting in the inclusion of 11 articles. In addition, one more article was included after reference tracking of the included articles. shows a flow chart of the systematic search.

Analysis

All the elements of PCC derived from literature were studied and discussed by two authors; conflicting ideas were resolved through discussion within the research team. Subsequently, the elements were clustered into core dimensions.

Empirical data

The empirical data of two separate qualitative studies that explored the perspectives of patients on good care for adult ADHD and bipolar disorder, by means of semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs), were used. These two patient groups were combined as in both studies the key issues expressed by the participants touched upon the description of PCC.

Participants and data collection

With respect to adult ADHD, participants discussed their experiences with and needs for adult ADHD care in the Netherlands in four FGDs (n = 30). Participants were included when they (1) had a primary ADHD diagnosis and (2) were 21 years or older.

People with bipolar disorder participated in six focus groups (n = 35) or were interviewed (n = 9) about experiences with and needs for mental healthcareFootnote1 . Inclusion criteria were (1) people who were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, (2) were above the age of 18 years old and (3) were stable at the time of the interview or focus group.

Since comorbidity is common with ADHD and bipolar disorder, in both studies participants with comorbidities were also included in the study. FGDs took 2 h and used a design that guided the discussions to reflect on all stages of care received: accessibility, diagnostic process and treatment. The interview guide had the same structure as the FGDs. FGDs and interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim; summaries were sent to participants for member check.

Data analysis

Data were analysed thematically using a coding sheet based on the integrated PCC model derived from the literature review. In addition, open coding was done to be able to include elements that were not mentioned in the literature but considered important aspects of good care by patients. The qualitative analysis software program MAXQDA 11.1.2 (Berlin, Germany) was used.

Ethical considerations

According to the Medical Ethical Committee of VU University Medical Center, the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act does not apply for the current studies with patients with bipolar disorder and ADHD. All the participants gave verbal or written informed consent for audiotaping, analysis and publication. Participation was on a voluntary basis and participants could withdraw from the study at any point in time, without giving reasons and without consequence. Anonymity of all participants was ensured in every phase of the research.

Results

In current literature, PCC is conceptualised in a variety of ways. All reviews included in this study integrated the conceptualisation of a variety of studies into a new conceptualisation, albeit at different levels of analysis and with a different scope. Some reviews strictly speak about the theoretical dimensions (or components or themes) of the concept of PCC, while others include a discussion of required skills, factors contributing and barriers to PCC as part of the conceptualisation. An overview of the included articles and the core dimensions by which PCC is described is provided in .

Table 1. Overview of the included papers.

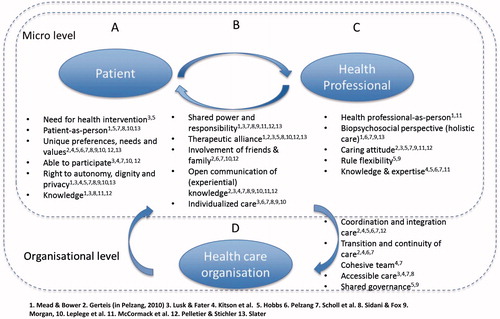

The elements addressed in literature were clustered into four dimensions (): “patient”, “health professional”, “patient–professional interaction” and “healthcare organisation”. The “patient” is conceptualised as a human being and has the right to be heard and receive tailor-made care and treatment (). The implications of this view for the interaction between health professionals and patients are also discussed by all articles, calling for a new style of communication and shared responsibility (). Furthermore, many articles argue that not only the person behind the patient but also the person behind the health professional, and his/her role and attitude, is essential for PCC, as the person behind the health professional influences the interaction (). Although a conceptualisation including patients, health professionals and their interaction is widely recognised and used, some scholars have argued that a greater focus needs to be placed on the organisational level of PCC and not solely on its constituent parts (). The dimensions of PCC are closely intertwined. For analytical purposes, we will discuss each dimension separately, juxtaposing what was found in literature with our empirical data, in order to understand how patients’ perspectives of good care align with these conceptualisations of PCC.

Patient

In PCC, the patient is first and foremost seen as a unique person – as “an experiencing individual” (Mead & Bower, Citation2000, p. 1089), with his or her “own way of perceiving and experiencing” (Pelzang, Citation2010, p. 913). Consequently, patients have “a heterogeneous response to illness” (Hobbs, Citation2009, p. 55). Thus, as opposed to the commonly held belief that all patients with the same diagnosis should receive the same treatment, in the PCC discourse it is emphasised that patients have unique preferences, needs and values in relation to their illness (Kitson et al., Citation2013; Mead & Bower, Citation2000; Morgan & Yoder, Citation2012; Pelletier & Stichler, Citation2014; Pelzang, Citation2010; Scholl et al., Citation2014; Sidani & Fox, Citation2014; Slater, Citation2006). Moreover, fully respecting the unique preferences of patients also implies that patients decide whether they even need or want care (Hobbs, Citation2009; Lusk & Fater, Citation2013). In addition to being unique, in PCC a patient is seen as able to participate in his/her own care (Pelletier & Stichler, Citation2014), and has the right to autonomy, dignity and privacy (Lusk & Fater, Citation2013; Slater, Citation2006).

In the stories of people with ADHD and bipolar disorders many examples of “being unique” and the desire to be treated accordingly appear. Prominent in these stories is the conviction that a person is more than his or her diagnosis:

[The therapist] should treat me as a person. That’s the most important: treat me as a human being and not as a problem. (Female, 51, bipolar disorder)

Really look at who you are as a person, and place the ADHD next to that person, because everyone has different problems with which he struggles or another history that troubles him. (Female, 33, ADHD)

A diagnosis, whether bipolar disorder or ADHD, is just one aspect of human life and coincides with other aspects such as family life, professional life and the person’s place as an individual human being in society. In addition to support for each of the elements of PCC regarding the patient that were found in literature, our data provides more in-depth insights into some of the elements.

First, an important aspect of considering “patients-as-persons”, not explicitly discussed in the studied literature, is that many patients stressed that they have a variety of strengths and competences, in addition to merely deficits associated with mental disorders, which can be used in the treatment trajectory. According to these patients, their strengths are hardly addressed in current healthcare practice:

It’s always like oh you are diagnosed with ADHD so you can’t study and you can’t concentrate (…). Turn that around and approach it more positively: you’re more creative, you’re more intelligent, you hear and see more, you’re better suited for a think-tank. (Female, 50, ADHD)

Sometimes they only speak about bipolar, and you think, I am more than just bipolar. I am a great reader, or speak my languages fluently, etcetera. (Female, 69, bipolar disorder)

The patients do not just ask for recognition of these strengths, but also for awareness that these strengths could act as a source for personalised treatment.

Second, many stories shared by patients support the idea that the way in which the diagnosed disorder works out for individual patients and their context is unique. There are differences between individuals in both their personal characteristics (I am a different person from you) and their experiences of illness (my ADHD is different from your ADHD). The symptoms, the severity of the symptoms and the problems that these symptoms cause vary from one individual to another, and can have a very different impact on the daily lives of persons living with it. In addition to the current conceptualisation, patients stress that preferences, needs and values are not just individually determined but are, to a certain extent, situational and can change over time. For the delivery of PCC, this means that personal desires and contexts help to fine-tune treatment to maximise effectiveness and satisfaction within that context:

When I am in nature I am in a flow. A lot is context dependent; at a different place on earth I am fine without medication. (Male, 57, bipolar disorder)

Third, patients appreciate the ability to share experiential knowledge with their health professional and thereby being appreciated as a person with knowledge about their disorder. This is often not the case as illustrated by the following quote:

“Once I was given the wrong pills and became very manic. When I said that I thought something was wrong, they said: ‘Nah, just keep on going, let’s finish this first’. (Female, 34, bipolar disorder)

Thus, according to patients, “good care” implies acknowledging, and being sensitive to, different forms of uniqueness. Patients generally desire to be treated with dignity and respect, attuned to their personal needs, preferences and values, with a focus on their individual strengths, and value the exchange of knowledge with their health professionals. Patients’ unique desires are not stable per se; they can be situational and may change over time.

Health professional

Just as the “patient” was re-conceptualised as a unique person PCC demands a new conceptualisation of the health professional as person, implying an additional set of characteristics. According to Steward (cited by Mead & Bower, Citation2000, p. 1088), a patient-centred health professional adopts a biopsychosocial perspective on illness and is “willing to become involved in the full range of difficulties patients bring to their doctors and not just their biomedical model”. In addition to knowledge and professional expertise essential to medical practice (Hobbs, Citation2009; McCormack, Citation2004; Pelzang, Citation2010; Scholl et al., Citation2014), the health professional is a person with a caring attitude which is understood as being respectful, empathic, honest and, above all, being present (Hobbs, Citation2009; Lusk & Fater, Citation2013; McCormack, Citation2004; Scholl et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the patient centred health professional is aware of and reflective to their own emotional responses (McCormack, Citation2004; Mead & Bower, Citation2000; Scholl et al., Citation2014). Rule flexibility is needed to determine “when and how to deviate from established norms and standards when the patient situation dictates” (Hobbs, Citation2009, p. 55). This means that the health professional needs to be assertive, rather than dominant or compliant, in relation to both the patient and their healthcare organisation.

Almost all patients acknowledged that their health professionals should – of course – have a caring attitude, including being empathic and listening carefully, but they also emphasised the importance of being knowledgeable and competent as this is essential for a valid diagnosis and obtaining the right treatment. Many patients value a healthcare professional who finds a balance between active and open listening and, as a professional with knowledge and expertise, is able to be directive when necessary.

He should also just ask the right questions, because he is still the therapist; it is important that the therapist gives a certain direction. (Male, 25, bipolar disorder)

Furthermore, several patients mentioned that health professionals seemed to have a preference for pharmacotherapy over non-pharmacological treatment, while patients rather preferred a broader perspective, including attention to lifestyle change, sports and nutrition.

A consultation with the psychiatrist is short. I would say, just try once to spend only half of the time on the pharmaceutical aspects, make it 50/50. (Male, 68, bipolar disorder)

In addition, in the stories of patients it came forward that it is important that not just the patient but also the health professional is considered to be a person, with his or her own background and experiences in life which could be expressed by time for self-disclosure or small talk.

At a certain moment, I reached the point with the psychiatrist that he was talking about his vacation and his sailboat. (Male, 25, bipolar disorder)

Thus, according to patients, it is important that a healthcare professional has clinical knowledge and expertise, is able to balance between being directive and being supportive, takes a holistic approach, and is considered as a person, rather than only as a health professional.

Interaction between patients and health professionals

As PCC demands a re-conceptualisation of “patients” and “health professionals”, this inherently implies a different relationship between them. The paternalistic doctor–patient relationship has to be transformed into a more personal relationship between the patient and the health professional in order to enact therapeutic change in patients (Mead & Bower, Citation2000b). According to Hobbs (Citation2009, p. 57), this therapeutic alliance develops through a “cyclical process based on the development of trust” and “involves availability and responsiveness of health professional and patient to one another”. Both the health professional and the patient are acknowledged as knowledgeable actors (Slater, Citation2006). The former should provide accurate and tailored information concerning the disease and treatment and the latter should be stimulated to share personal knowledge about his or her health condition and illness experience (McCormack, Citation2004; Mead & Bower, Citation2000b; Pelletier & Stichler, Citation2014; Pelzang, Citation2010; Scholl et al., Citation2014; Sidani & Fox, Citation2014). In other words, PCC demands “mutual participation” wherein power and responsibility are shared, an open exchange of knowledge is possible and where both the health professional and the patient reflect on their affects and how they mutually influence each-other (Mead & Bower, Citation2000; Pelletier & Stichler, Citation2014). Together, these aspects should result in an individualised care plan for each patient.

Many people with ADHD and bipolar disorder stressed the importance of a conductive therapeutic environment and therapeutic alliance. Especially, a good relationship between the health professional and the patient was often mentioned to be of major importance. In our study, several patients described this good relationship as feeling comfortable with and having trust in the healthcare professional, not only in his or her knowledge and skills but also in the willingness to listen without judgments, creating the possibility of open communication.

You only tell someone like that your deepest secrets if [you trust them] (…) there should be the right sort of feeling. It’s to do with your relationship, otherwise you wouldn’t do it that easily. (Male, 25, bipolar disorder)

For other patients, an important attribute to reach a good relationship was the ability to share decision-making power and responsibility, in both treatment and diagnostics. These participants felt they were mostly on the receiving end of the process where professionals distributed labels. Rather, they would like to see the diagnostic process to be a joint venture:

I am one of those people who for 10 years had to convince people I have ADHD but to them I was a hyperactive woman with returning depressions because of my hyperactivity … only later the diagnosis [ADHD] was given. (Female, 47, ADHD)

Despite the fact that a good relationship with the health professional could be influenced by the skills of the health professionals and the participation of the patient in his or her own care, having a connection with the health professional may also be based on personal preferences:

I was just about to say that (…), there is also something as having a “click” with a doctor, and I think I have been really lucky for having that with my psychiatrist. (Female, 34, ADHD)

Thus, according to patients, a good relationship is necessary to reach therapeutic alliance and consist of feeling comfortable and having trust in the health professional. It can not only be influenced by the behaviours and skills of health professionals, but also depends on personal preferences and a connection.

Healthcare organisation

The organisational structure and culture sets boundaries to the interaction, treatment options and overall patient-centeredness. As Saha et al. (Citation2008, p. 2) argue: “there is a great deal more to fix in the healthcare system than the interaction style of its practitioners” (Saha et al., Citation2008, p. 2). They argue that the healthcare organisation needs: (1) to have a committed and engaged board, (2) to empower health professionals to respond to patients’ needs and (3) to facilitate health professionals to “bend” the rules, if necessary, to deliver tailor-made care (Hobbs, Citation2009; Morgan & Yoder, Citation2012; Pelzang, Citation2010). Patient-centred healthcare organisation should deliver coordinated and integrated care, continuous care and accessible care (Kitson et al., Citation2013; Lusk & Fater, Citation2013; Pelzang, Citation2010; Scholl et al., Citation2014). Coordination and integration, refers to the collaboration within teams and between specialisms or different types of services, so that care for patients flows smoothly and is not fragmented (Hobbs, Citation2009; Pelzang, Citation2010; Scholl et al., Citation2014). Fragmentation of care creates discontinuity and prevents healthcare professionals from gaining full understanding of the patient’s illness or following his or her progress (Morgan & Yoder, Citation2012; Pelzang, Citation2010). According to Scholl et al. (Citation2014), integrated care also entails the integration of medical and non-medical care, such as alternative care or spiritual care and support services.

When reflecting on the organisational level of mental healthcare, patients mainly addressed the importance of a well-coordinated healthcare where different aspects of care are integrated to reach an individualised treatment plan. First, many patients put forward that a healthcare organisation needs to be equipped to deal with the fluctuating course of mental disorders. For example, several participants with ADHD explained that sometimes they were off treatment for a period of time. When they started to experience impairment again, or changes occurred that affected their functioning, they desired supervision by a therapist. However, most institutes have long waiting lists and, after some time, treat returning patients as new patients for financial reasons. This means the whole treatment process has to start all over again.

Say I stopped with my medications and I want to come back, I have to reapply, I have to wait for a couple of weeks and I get a whole new therapist (…) isn’t that weird? I find it hardly accessible and that I find a real pity. (Female, 50, ADHD)

The fluctuating course of bipolar disorder requires healthcare that is accessible at any time, as illustrated in the following quote:

Yeah, the accessibility is very problematic, especially outside of office hours, you know, the disease also doesn’t keep to a nine to five schedule. But the system is not designed for that. (Female, 34, bipolar disorder)

Second, most patients stressed that good collaboration within and between disciplines is important. In particular, many participants pointed at the beneficial aspects of alternative therapies. Even though these therapies may not have been proven effective as treatment for their disorder, these participants themselves experienced the positive effects of these therapies. They desired the integration of alternative therapies, or certain parts thereof, in their own treatment plan:

Listen, if the therapies aren’t compatible I can understand [that it’s difficult], but I don’t see why an alternative therapist can’t call a normal therapist so that they can talk about it. (Female, 34, bipolar disorder)

A third element that was regularly mentioned by patients is the continuity of care between various sectors in the healthcare system. For example, the time between a referral by a GP and the first meeting with a psychiatrist in specialist care should be short and referral between professionals from different disciplines, for example from a psychologist to a psychiatrist, should be smooth. However, many participants report that the time between seeking help and getting adequate care can be substantial, often referred to as “a long quest”, which may lead to dangerous situations.

But the GPs also don’t have a guideline how to treat someone with bipolar disorder, they rather refer you to someone else. But then you end up on a waiting list for a couple of months before you can have your first conversation with a psychiatrist. (Female, 51, bipolar disorder)

Some participants criticised that their professionals for financial reasons did not refer them to a specialist better equipped to address (parts of) their problems:

They should not be focused on running their own business, you know, I find it terrible when a psychologist or a psychiatrist treats you because they just want to keep you, because you are a golden goose and they are not prepared to refer you to someone who is better for you. (Female, 33, ADHD)

In short, according to patients, a healthcare organisation should provide the possibility for cooperation with therapist/coaches within and outside the system, to act and react to the fluctuating needs of patients. This entails better accessibility outside office-hours and ensures continuity of care, even after having left the system for while.

Discussion and conclusions

This narrative literature review integrated all elements of PCC as described in literature in one model of PCC. In addition, the perspectives of people with ADHD and people with bipolar disorder on what constitutes “good care” were investigated. Next, we analysed to what extent their stories on “good care” align to current conceptualisations of PCC. The core elements most elaborated upon in the reviews relate to the interaction between patients and health professionals, and the role of the health professional and the skills the health professional needs to deliver PCC, which primarily entails treating patients as unique individuals with their own experiences. Other scholars extend this discourse and argue that organisations play an important role as well, by either hampering or facilitating PCC.

Listening to the stories of patients provided no new core dimensions, but they helped in (1) understanding what the dimensions entail for people with ADHD and bipolar disorder, and (2) verifying and refining these dimensions. First, where in literature listening is described as an important aspect of a caring attitude of a health professional, our results add the importance of listening without judgment, which is only mentioned by Slater (Citation2006). This is important because sometimes patients feel ashamed of their own behaviour, more often they have experiences of not being accepted because of it. A second refinement is the acknowledgement of a personal connection with the health professional, in addition to the conceptualisation of the patient–professional relationship as described in literature. This is of great importance as personal and sensitive experiences and feelings are topics of conversation. A third refinement, in relation to the organisation, is that the need for flexibility is stressed, to be able to act and react on the fluctuating course of the disorders and the changing needs of patients. Patients ask for improvements in the accessibility of services, by extending office hours and easier re-admission into mental health clinic facilities when necessary. Fourth, the current conceptualisation refers to “patient-as-person”: patients stress the importance of seeing the patient as a person with positive sides and strengths, and not merely as a person with deficits, which is only scarcely described in literature (Slater, Citation2006). Finally, patients indicate that, next to the health professional’s expertise, they highly appreciate their own experiential knowledge to be taken serious too. After all, patients gain knowledge about their disorder, and even though each person’s trajectory is unique, patients feel that their individual stories on how to cope with the disorder are helpful in care.

A comparison of the perspectives of people with ADHD and people with bipolar disorder with other studies on patients’ perspectives on care, shows many similarities. The wishes of patients “to be listened to non-judgmentally” and “to pay attention to the possible change in needs” are also described in a study of Billsborough et al. (Citation2014) on support needs during periods of mania and depression for people with bipolar disorder. The desire of adults with ADHD for more accessible and continuous care, which includes treatments not typically offered for ADHD, have also been described in the UK in a study on patients’ experiences of impairment, service provision and clinical management (Matheson et al., Citation2013). The importance, as well as the potential problems, of a health professional acting professionally and demonstrating empathy as a person is also described by a study of Eliacin et al. (Citation2015) on the patients’ understanding of shared decision making in mental health setting and Williams et al. (1999) on the user perspectives on person-centeredness in social psychiatry.

Addressing the patient as “knowledgeable” or as an expert is mentioned by some scholars in the context of PCC (Corring & Cook, Citation1999; Eliacin et al., Citation2015; Leplege et al., Citation2007; Lusk & Fater, Citation2013; McCormack et al., Citation2010; Mead & Bower, Citation2000; Pelletier & Stichler, Citation2014; Sidani & Fox, Citation2014), but is more extensively and explicitly evident in the area of patient participation in healthcare and health research (Caron-Flinterman et al., Citation2005; Entwistle et al., Citation1998; Epstein et al., Citation2010). Acknowledging these other discourses on patients’ experiential knowledge within the PCC discourse could strengthen the epistemic position of patients in medical practice and challenge the dominant biomedical approach.

Few studies pay attention to the system in which healthcare professionals have to act. To move beyond the incidental patient-centred interaction between health professional and patient, we suggest that “patient-centeredness” should be perceived as a characteristic of a health system, which is responsive and adaptive to the needs of patients – a health system in which (organisational) structures and cultures are conducive to patient-centred practices. Such a health system “adapt(s) to the often unexpected and context-dependent requirements” (Epstein et al., Citation2010, p. 1492). This requires a move from the intentions of (groups of) individuals to structural change around patient-centred care. Combining the present PCC discourse with a multilevel perspective (Essink, Citation2012; Shields, Citation2013) and that of complex adaptive systems (Minas, Citation2014) could enrich endeavours to understand and scale-up patient-centred care. Such a process would add attention to system-wide cultures and structures to the current narrow focus on patient-centred practices (encompassing primarily patients and health professionals in their interaction).

Strength and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, it increases our understanding of the conceptualisation of PCC from a patient’s perspective in the field of mental health (outpatient psychiatric services) and contributes to reducing the gap in literature about this topic. Second, a narrative literature review was conducted using literature about the conceptualisation of PCC – providing the most current and relevant insights into the topic. A third strength is that we included perspectives of people with ADHD and people with bipolar disorder on healthcare.

In this study, we focused on the conceptualisation of PCC in mental health, using two psychiatric disorders as exemplary. A limitation of our study is that, although there were many similarities in the accounts of both patient groups on what constitutes “good care”, further research into the extent to which the identified refinements are applicable to other psychiatric disorders and somatic diseases is warranted. Furthermore, our analysis could be enriched by including and integrating theories and approaches of closely related developments in mental health, like recovery-oriented care, collaborative care and service-user participation.

In sum, this innovative study shows that what is considered “good care” by patients with ADHD and bipolar disorder resonates with key dimensions of PCC as found in literature. Furthermore, the study demonstrates the value of patients’ perspectives in the refinement of, and preferred emphasis in, the conceptualisation of PCC.

Declaration of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Notes

1 Data collection took place in the context of studies in collaboration with three outpatient clinics for bipolar disorder in The Netherlands (GGZinGeest Amsterdam, GGZinGeest Hoofddorp and Altrecht Bipolair, Utrecht): (a) a study on research priorities, in which patients' needs and wishes with regard to health care were discussed; and (b) a study on best practices in mental health care.

References

- Billsborough J, Mailey P, Hicks A, et al. (2014). ‘Listen, empower us and take action now!': Reflexive-collaborative exploration of support needs in bipolar disorder when 'going up' and 'going down'. J Ment Health, 23, 9–14

- Caron-Flinterman JF, Broerse JE, Bunders JF. (2005). The experiential knowledge of patients: A new resource for biomedical research? Soc Sci Media, 60, 2575–84

- Clissett P, Porock D, Harwood RH, Gladman JR. (2013). The challenges of achieving person-centred care in acute hospitals: A qualitative study of people with dementia and their families. Int J Nurs Stud, 50, 1495–503

- Corring D, Cook J. (1999). Client centred care means that I am a valued human being. Can J Occup Ther, 66, 71–82

- Duggan PS, Geller G, Cooper LA, Beach MC. (2006). The moral nature of patient-centeredness: Is it “just the right thing to do”? Patient Educ Counsel, 62, 271–6

- Eliacin J, Salyers MP, Kukla M, Matthias MS. (2015). Patients' understanding of shared decision making in a mental health setting. Qual Health Res, 25, 668–78

- Encinares M, Golea G. (2005). Client-centered care for individuals with dual diagnoses in the justice system. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv, 43, 29–36

- Entwistle VA, Renfrew MJ, Yearley S, et al. (1998). Lay perspectives: Advantages for health research. Br Med J, 316, 463–6

- Epstein RM. (2000). The science of patient centered care. J Fam Pract, 49, 805–10

- Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. (2010). Why the nation needs a policy push on patient centered health care. Health Affairs, 29, 1489–95

- Essink DR. (2012). Sustainable health systems, the role of change agents in health system innovation. Vianen, The Netherlands: BoxPress

- Gabrielsson S, Savenstedt S, Zingmark K. (2014). Person-centred care: Clarifying the concept in the context of inpatient psychiatry. Scand J Caring Sci, 29, 555–62

- Geller JL. (2012). Patient centered, recovery oriented psyhciatric care and treatment are not always voluntary. Psychiatr Serv, 63, 493–5

- Greene SM, Tuzzio L, Cherkin D. (2012). A framework for making patient centered care front and center. Permanente J, 16, 49–53

- Hobbs JL. (2009). A dimensional analysis of patient-centered care. Nurs Res, 58, 52–62

- Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, et al. (2011). Measuring patients' perceptions of patient-centered care: A systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med, 9, 155–64

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Envisioning the national health care quality report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1–18

- Johansson H, Eklund M. (2003). Patients' opinion on what constitutes good psychiatric care. Scand J Caring Sci, 17, 339–46

- Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. (2013). What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs, 69, 4–15

- Leplege A, Gzil F, Cammelli M, et al. (2007). Person-centredness: Conceptual and historical perspectives. Disabil Rehabil, 29, 1555–65

- Livingston JD, Nijdam-Jones A, Brink J. (2012). A tale of two cultures: Examining patient-centered care in a forensic mental health hospital. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol, 23, 345–60

- Lusk JM, Fater K. (2013). A concept analysis of person centered care. Nurs Forum, 48, 89–98

- Matheson L, Asherson P, Wong ICK, et al. (2013). Adult ADHD patient experiences of impairment, service provision and clinical management in England: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res, 13, 184

- McCormack B. (2004). Person centredness in gerontological nursing, an overview of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs, 13, 31–8

- McCormack B, Karlsson B, Jan DW, Lerdal A. (2010). Exploring person-centredness: A qualitative meta-synthesis of four studies. Scand J Caring Sci, 24, 620–34

- McGinty KL, Larson JJ, Hodas G, et al. (2012). Teaching patient-centered care and systems-based practice in child and adolescent psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry, 36, 468–72

- Mead N, Bower P. (2000). Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med, 51, 1087–110

- Mills I, Frost J, Cooper C, et al. (2014). Patient-centred care in general dental practice – A systematic review of the literature. BMC Oral Health, 14, 64

- Minas H. (2014). Human security, complexity and mental health system development. In: Patel V, Minas H, Cohen A, Prince MJ, eds. Global mental health: Principles and practices. New York: Oxford University Press, 137–66

- Morgan S, Yoder LH. (2012). A concept analysis of person-centered care. J Holistic Nurs, 30, 6–15

- Pelletier LR, Stichler JF. (2014). Patient-centered care and engagement nurse leaders' imperative for health reform. J Nurs Admin, 44, 473–80

- Pelzang R. (2010). Time to learn, understanding patient centred care. Br J Nurs, 19, 912–17

- Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. (2008). Patient-centered care and adherence: Definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurs Pract, 20, 600–7

- Robinson L, Bamford C, Briel R, et al. (2010). Improving patient-centered care for people with dementia in medical encounters: An educational intervention for old age psychiatrists. Int Psychogeriatr, 22, 129–38

- Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. (2008). Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc, 100, 1275–85

- Scambler S, Asimakopoulou K. (2014). A model of patient-centred care – turning good care into patient-centred care. Br Dent J, 217, 225–8

- Scholl I, Zill JM, Harter M, Dirmaier J. (2014). An integrative model of patient-centeredness – a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One, 9, e107828

- Shields LS. (2013). Understanding the complexities of the mental health system in India: Strategies for an accessible, integrated, rights-based approach. Enschede: VU University

- Sidani S, Fox M. (2014). Patient-centered care: Clarification of its specific elements to facilitate interprofessional care. J Interprof Care, 28, 134–41

- Slater L. (2006). Person-centredness: A concept analysis. Contemp Nurse, 23, 135–44

- Stewart M. (2001). Towards a global definition of patient centred care. The patient should be the judge of patient centred care. BMJ, 322, 444–5

- Stokes G. (2005). Person-centred care for residents with dementia. Nurs Resident Care, 7, 109

- Storm M, Edwards A. (2013). Models of user involvement in the mental health context: Intentions and implementation challenges. Psychiatr Q, 84, 313–27

- Trimbos-instituut. (2015). Ontwikkelingen in de zorg voor mensen met ernstige psychische aandoeningen. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut

- Williams B, Cattell D, Greenwood M, et al. (1999). Exploring person centredness, user perspectives on a model of social psychiatry. Health Soc Care Commun, 7, 475–82