Abstract

Purpose: The utility of self-management with people from minority ethnic backgrounds has been questioned, resulting in the development of culturally specific tools. Yet, the use of stroke specific self-management programmes is underexplored in these high risk groups. This article presents the experience of stroke therapists in using a stroke specific self-management programme with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds. Methods: 26 stroke therapists with experience of using the self-management programme with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds participated in semi-structured interviews. These were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically. Results: Three themes were identified. One questioned perceived differences in stroke survivors interaction with self-management based on ethnicity. The other themes contrasted with this view demonstrating two areas in which ethnic and cultural attributes were deemed to influence the self-management process both positively and negatively. Aspects of knowledge of health, illness and recovery, religion, family and the professionals themselves are highlighted. Conclusions: This study indicates that ethnicity should not be considered a limitation to the use of an individualized stroke specific self-management programme. However, it highlights potential facilitators and barriers, many of which relate to the capacity of the professional to effectively navigate cultural and ethnic differences.

Stroke therapists suggest that ethnicity should not be considered a barrier to successful engagement with a stroke specific self-management programme.

Health, illness and recovery beliefs along with religion and the specific role of the family do however need to be considered to maximize the effectiveness of the programme.

A number of the facilitators and barriers identified are not unique to stroke survivors from ethnic minority communities, nor shared by all.

The therapists skills at negotiating identified barriers to self-management are highlighted as an area for further development.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Self-management has, since the 1990s, become an increasingly integral part of the UK national strategy to manage people with long term conditions including stroke. The growing recognition of its importance is reflected by its inclusion in key clinical guidelines [Citation1]. Self-management programmes have shown to deliver positive impacts on quality of life and more appropriate use of health resources [Citation2]. However, there is growing concern that self-management programmes are not accessed by those considered “hard to reach” [Citation3], a phrase generally referring to a wide variety of people who have limited engagement with participatory processes [Citation4]. In the case of stroke, a number of barriers have been identified, including physical, cognitive and language limitations, but concerns regarding accessibility for minority ethnic stroke survivors have also been raised [Citation5,Citation6].

Exploring the experience of people from ethnic minorities and stroke within self-management approaches is both appropriate and timely due to current increasing interest in self-management and stroke. As the single most common cause of severe disability in adults in UK, stroke is of national concern [Citation7] with interventions to promote successful longer term outcomes, including self-management programmes, highlighted as priorities in national stroke strategies [Citation8,Citation9]. Within the UK stroke population, there are also clear indicators why the cultural appropriateness of any intervention should have primacy. Minority ethnic communities are the fastest growing sector of the UK population [Citation10] and adults from ethnic minorities, particularly South Asian and Black, are at higher risk of stroke than the general population; the incidence of stroke is twice as high for Black as for White populations [Citation8]. Although research in UK indicates that care provision is equitably provided [Citation11], outcomes reported in USA and New Zealand are reported as poorer for those from minority ethnic groups [Citation12,Citation13]. While equivalent outcome data are not available in UK, there are nonetheless indications that stroke survivors from ethnic minorities have higher levels of unmet needs post-stroke [Citation14] and are less likely to return to work [Citation15], thus indicating some inequity in outcomes relating to longer term management and social integration. As such, it is essential that the development of longer term programmes, such as self-management, is appropriate and sustainable for this growing sector of the UK society.

To date, there is a dearth of exploration on this topic. Recognizing concerns over poorer outcomes for minority ethnic stroke survivors in New Zealand, Harwood et al. [Citation16] developed a culturally and stroke specific self-management programme and found it to be more effective than provision of generic stroke information. However, while culturally adapted self-management programmes have been developed within the UK context for conditions such as diabetes and cardiac disease, albeit with mixed results [Citation17], stroke has until now been overlooked. Furthermore, UK-based programmes of self-management in stroke have not to date been investigated as to their utility and efficacy with stroke survivors from minority ethnic communities.

Kennedy et al. [Citation20] note the importance of considering professional influences on the implementation of self-management programmes and the role of the professional has been demonstrated as key in the perceived success of some, non-stroke, programmes [Citation21,Citation22]. The importance of this is emphasized when the programme is primarily initiated and facilitated by health professionals. This is the case for one such programme, which has emerging evidence of its efficacy [Citation18]. This self-management programme is both individualized and workbook based, drawing explicitly on social cognition theory and the work of Bandura [Citation19] in relation to promoting self-efficacy. The combination of this approach alongside the professional delivery is unique within stroke self-management programmes. In light of the increasing use of self-management approaches in stroke, the uncertainties relating to its utility and efficacy among different ethnic groups and the higher incidence of stroke in minority ethnic communities, the need to explore the appropriateness of currently used self-management approaches post-stroke is apparent. While such understanding could be explored through the participants’ perspective, the call to examine the professional perceptions of the self-management process is particularly pertinent for an approach in which they are both the initiator and facilitator. The aim of this study was therefore to explore the experience of healthcare professionals in using an individualized self-management approach with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds.

Method

Design

As this study aimed to explore the professionals’ experience, a qualitative approach was deemed most appropriate. Philosophically, the research draws on hermeneutic traditions through which exploring and interpreting the experience of the participants was the primary focus of enquiry [Citation23,Citation24]. In-depth interviews allow for an exploration of complexities in people’s accounts and therefore was the method selected [Citation25]. Interviews were semi-structured and used a broad topic guide to explore; the participants understanding of self-management, the health professionals’ experience of using the self-management programme with stroke survivors from ethnic minorities, its perceived effectiveness, facilitators and barriers. Prompts within the interview further examined the participants’ concept of ethnicity and their role as a professional within the self-management process. These topics were identified through the literature on self-management and ethnicity studies.

Participants

Participants were purposively sampled healthcare professionals who were trained and had current experience of using the self-management programme with stroke survivors from minority ethnic communities. A previous unpublished survey had indicated that the number of healthcare professionals who had used the self-management programme with stroke survivors from ethnic minorities was very limited (20%). Subsequently, the amount of experience in its use was not a limitation to participation. However, participants were sampled for a range of professions and working environments. Participants volunteered following an email request sent through the database (n = 350) of people who had completed training in the self-management programme and previously given consent for further email contact. A purposive sample of 25 participants was sought to allow for detailed examination of their narratives, while exploring a range of experiences [Citation26]. All volunteers were recruited and participants gave written informed consent prior to being interviewed.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by the primary author and arranged at a location and time suitable for each participant. They were carried out in homes, University and Social Service facilities. With permission, interviews were audio recorded and lasted 1 h on an average (range 34–100 min). To assist with the interpretation process, additional contextualizing notes were taken during and after, including body language and discussions which arose after the digital recorder was turned off. All recorded verbal data were transcribed verbatim and contextual notes added.

Data analysis

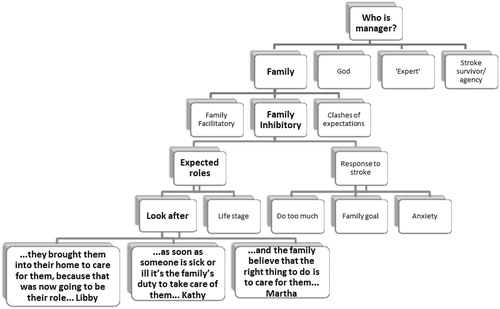

The data were analysed thematically drawing connections within and between participants, while remaining firmly based in the participants words [Citation27]. Atlas.ti (Version 5.2 by Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) computer software was used to facilitate data management. Initially, all transcripts were read several times and initial thoughts noted. Following this, open coding predominantly at sentence level was conducted. These were later collated to family codes and finally the overriding themes which will be presented (see for an example). The texts were then re-read with specific reference to the themes to confirm their appropriateness within context and to look for conflicting examples. The analysis was conducted by the prime author, a sample of transcripts independently coded by a second researcher after which discussion was held to resolve very minor analytical differences and the developed themes were discussed and agreed by the research team. Contextual notes made during the interviews were used to assist with the interpretation of meaning within the analysis process.

A reflexive diary was kept during the study [Citation28]. This was considered particularly important as the researcher has a background in neurological therapy, although at the time of the data collection and analysis was not trained in the self-management programme. The professional status of the researcher was known to the interviewees and impacted positively on rapport building through shared experience, contextual understanding and language. However, the decision to delay exposure to the training programme itself facilitated a lack of preconceptions on either the utility or efficacy of the programme with stroke survivors. Indeed, it also prevented assumptions of shared specific professional knowledge with regard to self-management, requiring participants to explain their understanding of underlying concepts. The study was granted ethical approval by the School of Health Sciences and Social Care ethics committee (Ref 11/STF/03) and all participants have been given a pseudonym.

Results

Twenty-six people volunteered, all of whom consented and were interviewed. A summary of the participants is given in in which a range of professions, experience within their profession and in using the self-management approach is illustrated.

Table 1. Participants.

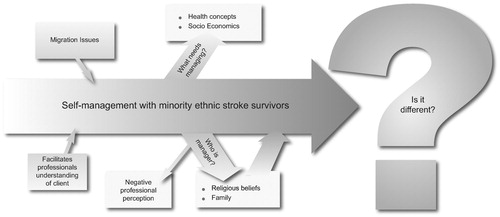

Three themes emerged from the data, the first two of which highlight issues deemed by participants to be specific to minority ethnic stroke survivors. First is “what needs self-managing?” which raises issues around the concepts of stroke and recovery. This theme draws attention to the need to consider underlying theories perceived by participants as required for self-management as well as conflicting priorities.

The second theme dissects the idea of self in self-management by asking “who is the manager?” Through this theme aspects of God and agency are presented, alongside complex consideration of the particular significance of family and the professionals themselves.

The final theme contrasts with and in part contradicts the first two in questioning whether the process of self-management is indeed different for stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds at all. “Self-management as a shared concept” illustrates the perception that self-management is both evident and accessible whatever the ethnic background. These themes are summarized in .

What needs managing?

As participants discussed their experience of using the self-management programme with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds, the issue of what they were trying to manage was raised as of particular relevance. Health and illness beliefs were perceived by participants as being central to this concept.

Health beliefs – stroke

Participants perceived that underlying health beliefs of both stroke and recovery were frequently challenging, yet lay at the heart of promoting successful self-management. Farah, e.g. while discussing stroke survivors from her own Bangladeshi community, explained her perception that the understanding of stroke itself was a considerable barrier to engagement with self-management, as stroke survivors had to first comprehend the basics of stroke itself.

“But a stroke is quite … like it’s fairly new to people … when you try and explain it to them they find it quite shocking how the brain is in charge of you know their arm or like why they can’t speak or why they’ve got the facial stroke, or why they can’t swallow. So it’s really like … it’s new to them, very new.”

Farah described how this was a frequent position and for approximately half of the minority ethnic stroke survivors she works with this education would have to precede focus on the self-management programme, a view generally supported by other participants.

Health beliefs – recovery

Other participants noted particular beliefs in the recovery process. Martha, e.g. commented that in her experience pre-existing attitudes to illness held by some people from minority ethnic communities sometimes resulted in rest and care being held as the optimum treatment. Max and Farah among others described their experience that the stroke survivors’ belief in tablets to cure resulted in an attitude that one day they will wake up and the problem will have disappeared. Similarly, Rose and Saatvick highlighted that they are aware their clients, frequently use traditional herbal medications, believing these would result in an effective change in their condition.

“Sometimes people’s medical perception and ideas are very different. So … I’ve got patients that you know don’t want to take sometimes the medication they’re prescribed because they want to use herbal stuff, and sometimes things are sent over from for example Africa. Or they’ve got beliefs about family members you know back in different countries, have had similar experiences and they tried this. And … so sometimes that can be quite challenging because you’re working from a western medicine point of view and they’re coming from a very different idea … and that can be difficult.” Rose

More generally 11 participants discussed their view that stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds frequently held concepts of a “quick fix” to their stroke symptoms which ideally should be delivered by the professionals. Such a view was seen as a challenge for the health professional in promoting the self-management programme, which was seen to require a longer term commitment, predominantly driven by the stroke survivor themselves. As a consequence of these differing attitudes to recovery, the professionals described a clash in approaches between themselves and the stroke survivor resulting in the self-management programme being considered unviable with judgement of potential non-compliance, illustrated in the following extract.

“you might get a bit more of an expectation from people from those cultural backgrounds that aren’t westernised, that you know you’re the therapist, you’re the expert in the field, you’re supposed to fix me … And in that sense it may be a complete nonstarter, because the idea of it being something that they have to sort of drive themselves rather than having someone else fix for them is not something that goes over very well.” Libby

Health beliefs – engagement

The issues noted above appeared to pose somewhat of a dilemma for the healthcare professionals. All were able to articulate what they perceived to be individual beliefs which affected the successful application of the self-management programme. Furthermore, the majority recalled that health beliefs were highlighted as a key mediator to self-management in their training. Indeed, Martha drawing on Bandura’s model of self-efficacy suggested that the self-management approach itself was a useful tool to help overcome the barrier to different health and recovery expectations and beliefs. However, on questioning few health professionals routinely and specifically asked their clients about their held beliefs. Much of the experience they described was based on third party or retrospective reports or even generalized cultural training provided at the workplace. As they discussed issues related to health and illness concepts, participants acknowledged that this was an area they needed to develop for the successful utilization of the self-management approach.

Health beliefs – questioned importance

One participant presented a contrasting view suggesting that several previously identified “cultural barriers” including health beliefs should be more appropriately reconfigured as “social barriers” which indeed cut across all cultural/ethnic groups. As she describes:

“Hmmm … perhaps … it’s not to do with Bengali, it’s to do with people living in socioeconomic deprivation. And that is what affects their self-efficacy … and we are muddling it up with their culture or ethnic background … but living in poverty, does it mean that it’s harder for you to self-manage your life and what you need and what you want to achieve out of your life?” Wendy

For Wendy, priorities were frequently not the health beliefs, stroke or its related consequences per se, but the wider social factors which influenced the individual’s capacity to address their broader life condition. Wendy had yet to discuss this with her team nor did she feel confident in her own judgement.

Who is the manager?

The second theme drawn from these narratives questions the self in self-management, exploring who is deemed to be the “manager” of an individual stroke survivor in their recovery pathway. As indicated in the previous theme, concepts of the “expert” to “fix” were raised. More specifically the role of God/Allah or other deities and family were seen to significantly influence this process. An adjunct on this theme is the professional as gatekeeper to the management process.

Religious beliefs

For nine of the participants, an approach to life which included fatalistic beliefs and the concept that “God’s will” will dictate the outcome of an adverse health event, were particularly challenging in promoting self-management with minority ethnic stroke survivors. These views were associated with multiple faiths including Islam, Hinduism, Judaism and Christianity.

“My understanding is God or Allah kind of has overall control … not overall control … but kind of their path is in his hands … Therefore it’s almost … the opposite to this self-efficacy, it’s the idea that, actually … you can’t change situations … it’s in the hands of Allah. Therefore, as a result of that, trying to get someone to take a more kind of self-management approach, it can be quite challenging.” Pippa

Despite these challenges, religion/spirituality and prayer were not necessarily seen as a block to self-management and other examples were cited where they worked simultaneously. In one example, Lucy described how prayer acted as a motivator which facilitated the work with the professional.

“It’s more noticeable how Asian population, obviously you know they’re kind of a bit more spiritual in a way … And so they will kind of be praying to get better, that kind of thing. So obviously that helps to motivate … because they’re wanting to get better … sometimes it can go the other way as well that they don’t feel that they need to do anything about it you know. But on the whole you know normally they’re the ones … they want to get better and they’d be kind of doing the praying and they’d be working with you as well.”

Similarly, participants emphasized that they should not assume that all stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds were religious. Like the health beliefs, participants went on to explain that what was required was an understanding of spirituality and a willingness by professionals to engage in how religion was integrated or not into the lives of the individuals. But, in contrast, spirituality was seen as an already established part of therapeutic models, specifically within Occupational Therapy, and therefore was something with which some of the health professionals were comfortable engaging.

Family

The family was also seen as a central influence on the individual. Overall, the participants felt that the minority ethnic communities they worked with had a stronger sense of family than the Caucasian population and family members were invariably around during sessions. However, the role of the family in self-management was described as complex, both seen as acting as facilitators to the process but also potentially inhibitors. Part of the complexity was deemed to be due to a clash of expectations between the stroke survivor, their family and the professionals.

Family – facilitatory

Twelve of the participants described their positive experiences of family members supporting the self-management process. A prime example was their willingness to support the individualized goals “hands on” when the therapist was not there, either following activity programmes or encouraging strategies to promote independence. The community-based professionals in particular valued this involvement due to the limited number of visits they were able to complete. But equally, hospital-based professionals such as Joan highlighted the closeness and positive relationships within Asian families and their active support in promoting independence in activities on the ward.

“I think the relatives are preferable in my opinion … in my humble opinion. And I wouldn’t say that that would work for every ethnic group as well, because um … I don’t know, the Gujarati population are very hands on and very there and willing to help … Also willing to translate, willing to come into sessions, wanting to be there at sessions.” Joan

In another example, Saatvick explained how a stroke survivor’s goal to walk outside was supported by the woman’s daughter who walked with her to social gatherings, the temple and shops when the therapist was not present. He went on to describe how in this instance that family assistance was not just helpful but essential as in this particular community, Gujarati, it was not usual for a woman to go out alone.

Family – inhibitory

Despite these positive experiences 18 participants noted that family involvement was not always beneficial in promoting self-management with the stroke survivor. The most commonly cited concern was the families desire to “look after” the individual and an anxiety at allowing them to challenge themselves to do tasks considered difficult or potentially unsafe. Indeed, three participants (Kathy, Saatvick and Debbie) all commented that “it was a well known fact” that families of ethnic minority stroke survivors want to do too much and thereby limit the potential development of self-management skills, as Kathy describes.

“I think the Indian ethnic group with their extended family and you know as soon as someone is sick or ill it’s the family’s duty to take care of them and they’ve got that certain structure with you know the daughters help the mum and … I know people find it really difficult for the patient in that situation to actually take some control and do things for themselves, because the culture is so strong that you know everyone does things for that person, and it might be offensive to not let them do that for them.” Kathy

It is of note that while some of the discussions in this area were based on personal experience of working with families from ethnic minorities, the professionals also drew on diversity training provided by their employer as a basis for their concepts of family structure and expected behaviour.

This perceived desire to look after relatives post-stroke was deemed to have practical implications on the promotion of self-management. Participants discussed examples of how the family actively prevented the stroke survivor from practising the steps they had identified in their own programme, insisting they rest and take no risks. Furthermore, participants reported the “danger” that family members would offer their own perception of what the individual should try to achieve, limiting the potential for client led goals.

While this challenge was highlighted as frequently associated with ethnicity, often as a consequence of the family members understanding of stroke and recovery, other reasons revolved around the programme itself. Debbie, e.g. suggested that the individualized focus of the programme inhibited her involvement with family members. On reflection, she discussed how wider inclusion was required particularly with family members centrally involved with care provision, as was often the case with minority ethnic stroke survivors.

Family – complexity

As a contrast to the frequently discussed “over caring family”, participants described scenarios where that stereotype had been used as an excuse by the stroke survivor themselves to avoid the hard work of regaining independence. Phrases such as “messy”, “clashes” and “internal conflict” were used to describe some of the professionals’ experiences in negotiating effective self-management within the wider familial context.

Highlighted in these discussions was the complexity of inter-generational caring and the changes in familial structures over time. Indeed Clare noted that an individual stroke survivor is only one part of family life and consequently it is essential that professionals understand the complexities of needs and desires of the family more broadly in order to work effectively. However, this scenario created tension for the professionals, for while they accepted that they wanted and to an extent needed the family to support the self-management approach, they were reluctant to increase the burden on carers they perceived as being over-worked, a common reflection particularly for younger female carers. Furthermore, participants noted that they were often reticent in exploring the potential complexities of the family involvement in self-management, as Libby explains:

“I don’t know I’ve discussed it specifically with any of the people that I’ve worked with. It can be a bit of a sticky situation to try to get to the bottom of why they’re not engaging … and you’re trying to understand where they’re coming from without necessarily pressing buttons. It can be quite difficult in a family where there’s tension …” Libby

It would appear that the complexities of competing agendas result in a challenging environment for the professionals to effectively promote self-management. These were particularly highlighted in minority communities where the perceived “rules” of family engagement were not fully understood by the professionals.

Professional – gatekeeper

The final aspect of this theme throws focus back on the professionals themselves. While the participants in this study had all used the self-management programme with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds, they expressed concern that some colleagues may be reluctant to do so, based on ethnicity. Kathy, e.g. discussed that held stereotypes such as that of “the culture of everything is done for you” may limit the use of the self-management programme as therapists deemed it unlikely to succeed. Gary further articulated that professionals may “chicken out” of using the programme on the basis of ethnicity. This view was explained in part by reference to the specific expectations therapists may hold, as Gary explains.

“clashes of culture … misunderstanding. Patients’ ideals not fitting with the game plans of the therapists that they’re working with. It’s the easy card to pull isn’t it – it’s ‘cos he’s black, or it’s because they’re different isn’t it?”

For Cilla, work was still required for professionals to break down “it’s a cultural thing” in order to facilitate the use and development of self-management in practice. Consequently, some professionals were deemed to be the sole managers of the self-management programme by not initiating with the stroke survivor at all.

SM as a shared concept

The two previous themes have focussed on influences perceived to specifically impact on self-management as a consequence of ethnicity, predominantly negatively. The third and final theme in contrast reflects the expressed view that ethnicity is frequently either a non-issue while facilitating the self-management programme or may indeed enhance the process.

With only two exceptions, all of the participants discussed positive experiences of using the self-management programme with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds. As Helen stated, “I think it [ethnicity] makes no difference at all” which she then followed with several examples across different ethnic groups of how the programme had been effectively adopted. Participants did acknowledge that a lack of shared language could create hurdles, but that the use of interpreters, colleagues, family members and more time could overcome this barrier in most circumstances.

Furthermore, specific features of difference that were raised were often somewhat contradicted by paralleling the experience with the ethnic majority, as demonstrated by Lucy.

“Our Asian population on the whole they want to be better but they always feel they need the support of the family to be better. You know they always feel that, you know … they have the support, they’d do better … you know they do better definitely. Obviously with the White British as well, when they have the support where they’re really disabled, it really helps”. Lucy

Such dialogues question the “unique” position of difference based on ethnicity previously described.

Indeed, three of the professionals highlighted that not only was the self-management programme appropriate for stroke survivors generally, but it had particular benefits when used with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds, as Kathy explains.

“I’ve had no difficulties with it [self-management programme]. I’d say it’s helped even, because for me it’s allowed me to learn what’s important for their culture. So you know having goals around getting to church and um … volunteering for church, and the kind of foods that they like to eat and what time of day they like to eat. So I’d say it’s helped me to understand their culture more.” Kathy

The individual focus of the approach was seen to prevent the professionals from making assumptions about beliefs and roles and encourage them to enquire about the individuals’ life in order to facilitate the process of progress reflection and goal planning.

In contrast to the sense that ethnic background had limited influence on the success of self-management, participants also highlighted situations in which it was perceived to actively facilitate the process, specifically focusing on migration histories as Amy describes.

“For me it goes back to life history and trials and tribulations. Landing here in the sixties or seventies you have those self-management strategies already engrained in you because it was part of your life before … If you ask a lot of older Africans or older Afro Caribbean’s, the underlying core is nobody’s going to help me unless I help myself. … so you have to help yourself in order for others to help you.” Amy

Farah, Gary and Amy all discussed this in some detail illustrating how the process of migration itself and the consequent adjustment required to re-form their lives in a new country, was evidence of successful self-management and goal setting. In their view, this armed an individual with a myriad of tools to tackle the management of their life post-stroke and furthermore gave the health professionals concrete examples that they could utilize to facilitate the development of self-management post-stroke.

Discussion

The three themes derived from this study demonstrate the complex experience of facilitating an individually directed self-management approach in minority ethnic stroke survivors. On one hand, the majority of professionals who volunteered for this study have successfully, in their opinion, achieved the task. They illustrated a range of examples where not only was the approach successfully integrated into the long term management strategy, but that by using it they were able to draw on the stroke survivors previous experience of self-management, often enhanced by nature of their ethnic status and related experience. The professionals discussed how their over-riding experience was that self-management was not unique to any ethnic group in everyday life and therefore questioned why it should be considered such in illness.

Despite this assertion and demonstration of its general utility, the participants of this study also illustrated examples that contradicted the apparent equity. This contradiction was not in the capacity of the approach to be effectively used per se, but in the additional factors which were perceived to relate to ethnicity which were necessary to negotiate. Hence focus is drawn to barriers and facilitators perceived to derive from the stroke survivors and their beliefs, their families, and professionals in achieving effective self-management. Interestingly, these same factors were hypothesized by Harwood et al. [Citation16] as central to the poorer stroke outcomes noted in Maori and Pacific communities in New Zealand. As these issues are now discussed, parallels in the literature will be drawn that either support or question the centrality of ethnicity within this debate.

One example was the challenge in traversing differences in knowledge and understanding of the underlying medical event and recovery. A number of layers were presented in this challenge, from the underdeveloped knowledge of stroke and the role of the brain, to alternative mechanisms of recovery which were deemed to lie outside that understood by the professionals. Such factors have been previously identified in different contexts. For example, alternative explanatory processes of stroke and its recovery have been identified in non-Western communities [Citation29–32], and poor stroke knowledge in minority ethnic groups is a common research finding [Citation33–35]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that differences in recovery concepts based on cultural understandings may influence the therapeutic interaction [Citation36] and the role of the professional as the expert has particularly potency in minority ethnic communities [Citation37]. Consequently, there is some support for this finding, albeit not specific to self-management. However, literature also indicates stroke understanding outside of the medical framework is apparent in white Scottish nationals [Citation38] and that recovery is defined differently even within ethnic/cultural groups [Citation39]. Furthermore, these different understandings such as the desire for a “quick fix” are deemed to influence the success of self-management generally [Citation40]. Consequently, it is unclear if the participants of this study are highlighting issues that are directly associated with ethnicity and self-management or alternatively the focus on minority ethnic communities illuminates the very specific nature of therapeutic and medical concepts, the language of which lie outside the everyday experience of many of their clients irrespective of ethnic background.

This study also raises questions about the capacity of professionals to negotiate these potential differences. While the success stories demonstrate this ability, the concerns that colleagues may “chicken out” suggests either a lack of confidence in the skill to do so or the powerful impact of stereotypes on decision-making, a concern previously highlighted [Citation41,Citation42]. Furthermore, the theory outlining the importance of health knowledge within self-management was accepted, yet the information required to support its implementation was either rarely sought or was drawn from generic training on cultural differences. Protheroe et al. [Citation43] suggest that the effectiveness of self-management is dependent on the professionals’ capacity to recognize the clients’ specific information needs and processes of engagement. This study indicates that this individualized recognition is complex and there may be a disconnect between theory and practice which would benefit from further exploration.

A second area highlighted in this study was expressed difficulties in balancing the concept of self within the complexities of other potential managers. The influence of religion in this study mirrors in part related literature. Fatalistic beliefs, often associated with Islam but also relevant in other religions, have been described previously as challenging to active engagement with rehabilitation generally [Citation44,Citation45], although it is accepted that this position has been challenged and the positive role of prayer and individual agency acknowledged [Citation46,Citation47]. This literature and the narratives from the participants would suggest that religion as an influence on self-management is not unique to minority ethnic communities who may or may not be religious, and is furthermore not a barrier per se, but requires skilful engagement with which the professionals may or may not feel competent to engage. Previous literature supports a view that such engagement is limited within rehabilitation generally [Citation48]. This study, in contrast illustrated an accepted need and capacity to understand and be respectful of individually held religious beliefs, although the difference between professions as discussed is noted. How professional models and practice engage and incorporate religious beliefs within self-management programmes is an area of further inquiry.

While religion was explored as a potential challenge to agency, in this study it was rather the interplay with the family that was highlighted as the most contentious in promoting self-management. On one hand, there was some indication that the inclusion of the family could positively enhance the self-management process. However, the focus was more concretely placed on the complexities and inhibitory role of the family. The professionals in this study consistently associated this with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds due to their perceived enhanced familial bonds and complexity of family interactions. Interestingly, the wider stroke field has highlighted positive involvement of families within rehabilitation [Citation49]. How professionals perceive this involvement however is limited, although Brashler et al. [Citation50] note that professionals often view families as “irritants” in post-stroke rehabilitation and Strudwick and Morris [Citation42], specifically focusing on ethnic minorities, note the predominance of stereotypes such as the “caring family” as barriers to meaningful and appropriate professional and family engagement post-stroke.

Discussion of the role of family in promoting self-management in adults is underdeveloped in current literature, although their potential influence both positive and negative is noted in some fields [Citation51]. This limited engagement has resulted in calls for a reconceptualization of the self-management approach to specifically consider a more family inclusive model [Citation52]. The importance of family generally in self-management has been in part acknowledged by the developers of this self-management programme who have recently launched a carer’s workbook. An examination of its impact on the capacity of the professionals to engage with family members would be of significant interest in this underexplored area. Specifically though, given both the limited literature and complexity of the participants experiences, the interaction between professionals and families from minority ethnic communities should not be overlooked.

As noted earlier, it is accepted that a number of the issues raised in this article are not necessarily exclusive to stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds and also may not be relevant to all. Heterogeneity within ethnic groups is as important to explore as assumed homogeneity. Furthermore, as suggested by Wendy in relation to socioeconomic position and reiterated by Nazroo and Williams [Citation53] and Bhopal et al. [Citation54], ethnicity is only one part of a complex web of influences and further research on how these different factors intersect within rehabilitation and self-management specifically is required.

However, these narratives highlight a number of important issues. Firstly, that professionals do not perceive this individualized self-management programme as being culturally or ethnically exclusive. Nevertheless, issues do arise with the knowledge and capacity to effectively negotiate differences in understanding of stroke and recovery and to fully appreciate and manage the complexity of factors which may influence engagement with the self-management process, particularly relating to the family. These areas require further study in isolation but also within the context of the whole system of self-management, drawing on both institutional processes and patient experience.

Stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds may be “hard to reach” within self-management programmes, but this study suggests that “reaching” them is entirely possible. Furthermore, perceived difficulties lie as much with the professional as the stroke survivor and their wider family and many parallel those identified for stroke survivors from the ethnic majority. Thus, this study highlights a need for self-management programmes to be responsive to the contextualized individual needs of stroke survivors whatever their ethnicity and for facilitators to have the skills to do so. A focus on the skills and capacity of the professional to facilitate effectively is of particular importance in programmes such as the one discussed in this article where they are the gate-keeper for access and the means whereby the programme is delivered.

Limitations

It is acknowledged that this study presents only the subjective experiences of a self-selecting group of professionals. Consequently, it neither presents the views of the stroke survivors themselves or the implementation in practice. Both would be appropriate areas of further enquiry. Given that a number of participants discussed their previous involvement and influence of cultural training on their interaction with clients, this would have been useful information to collect and also an area of further investigation.

Conclusion

This qualitative study with healthcare professionals would indicate that ethnicity should not be considered a limitation to the use of an individualized stroke specific self-management programme. However, it does highlight barriers to its use, many of which relate to the capacity of the professional to effectively navigate through the differences of understanding once they have been identified. The family is also highlighted as an area of potential assistance and conflict and further work to explore how they can best be incorporated in the self-management process is required. While these issues have been identified as important in the promotion of self-management with stroke survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds, we contend that their relevance is more general.

Declaration of interest

One of the authors of this article (F.J.) is the founder of Bridges stroke self-management programme, which is explored in this article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants for their time and expertise. Additional thanks are due to Arnold Lloyd and Tess Baird for their support and the reviewers for the very helpful comments.

References

- Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National clinical guideline for stroke. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2012

- De Silva D. Helping people help themselves. London: The Health Foundation; 2011

- Kennedy A, Gask L, Rogers A. Training professionals to engage with and promote self-management. Health Educ Res 2005;20:567–78

- Brackertz N. Who is hard to reach and why? ISR Working Paper: University of Michigan; 2007

- Jones F, Riazi A, Norris M. Self-management after stroke: time for some more questions? Disabil Rehabil 2013;35:257–64

- Kendall E, Catalano T, Kuipers P, et al. Recovery following stroke: the role of self-management education. Social Sci Med 2007;64:735–46

- National Audit Office. Progress in improving stroke care. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General HC 291;2010

- Department of Health National Stroke Strategy. London: Department of Health; 2007

- Wolfe C, Rudd A, McKevitt C, et al. Top ten priorities for stroke services research. London: Kings College London; 2008

- Lievesley N. The future ageing of the ethnic minority population of England and Wales. London, UK: Runnymede and the Centre for Policy on Ageing; 2010

- McKevitt C, Coshall C, Tilling K, Wolfe C. Are there inequalities in the provision of stroke care? Stroke 2005;36:315–20

- McNaughton H, Feigin V, Kerse N, et al. Ethnicity and functional outcome after stroke. Stroke 2011;42:960–4

- Ottenbacher K, Campbell J, Kuo Y, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities exist in post acute rehabilitation outcome after stroke in the United States. Stroke 2008;39:125–30

- McKevitt C, Fudge N, Redfern J, et al. UK Stroke survivor needs survey. London, UK: The Stroke Association; 2010

- Busch M, Coshall C, Heuschmann P, et al. Sociodemographic differences in return to work after stroke: the South London Stroke Register (SLSR). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:888–93

- Harwood M, Weatherall M, Talemaitoga A, et al. Taking charge after stroke: promoting self-directed rehabilitation to improve quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2012;26:493–501

- Wilson C, Alam R, Latif S, et al. Patient access to healthcare services and optimisation of self-management for ethnic minority populations living with diabetes: a systematic review. Health Social Care Community 2012;20:1–19

- McKenna S, Jones F, Glenfield P, Lennon S. Bridges self-management programme for people with stroke in the community: feasibility randomised controlled trial. Int J Stroke 2013. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1111/ijs.12195

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: New York: Worth Publishers; 1997

- Kennedy A, Rogers A, Bower P. Support for self care for patients with chronic disease. BMJ 2007;335:968–70

- McDonald W, Rodgers A, Blakeman T, Bower P. Practice nurses and the facilitation of self-management in primary care. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:191–9

- Rogers A, Kennedy A, Nelson E, Robinson A. Uncovering the limits of patient-centredness: implementing a self-management trial for chronic illness. Qual Health Res 2005;15:224–39

- Denzin N, Lincoln Y. Introduction. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, eds. The landscape of qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2013:1–42

- Maggs-Rapport F. Combining methodological approaches in research: ethnography and interpretive phenomenology. J Adv Nurs 2000;31:219–25

- Miller W, Crabtree B. Depth interviewing. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, eds. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Inc; 1999:89–108

- Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. 3rd ed. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:11–17

- Bryman A, Teeran J. Social research methods. Canadian edn. Canada: Oxford University Press; 2005

- Al-Oraibi S. Stroke patients in the community in Jordan. PhD Thesis University of Brighton; 2002

- Hundt G, Stuttaford M, Ngoma B. The social diagnostics of stroke-like symptoms: healers, doctors and prophets in Agincourt, Limpopo Province, South Africa. J Biosoc Sci 2004;35:433–43

- Mshana G, Hampshire K, Panter-Brick C, Walker R. Urban-rural contrasts in explanatory models and treatment-seeking behaviours for stroke in Tanzania. J Biosoc Med 2007;40:35–52

- Norris M, Allotey P, Barrett G. “I feel like half my body is clogged up”: lay models of stroke in Central Aceh. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1576–83

- DuBard C, Garrett J, Gizlice Z. Effect of language on heart attack and stroke awareness among U.S. Hispanics. Am J Prev Med 2006;30:189–96

- Ellis C, Egede L. Racial/ethnic differences in stroke awareness among veterans. Ethn Dis 2008;18:198–203

- Jones S, Jenkinson A, Leathley M, Watkins C. Stroke knowledge and awareness: an integrative review of the evidence. Age Ageing 2010;39:11–22

- Mold F, McKevitt C, Wolfe C. A review and commentary of the social factors which influence stroke care: issues of inequality in qualitative literature. Health Soc Care Commun 2003;11:405–14

- Banerjee A, Grace S, Thomas S, Faulkner G. Cultural factors facilitating cardiac rehabilitation participation among Canadian South Asians: a qualitative study. Heart Lung 2010;39:494–503

- Townend E, Tinson D, Kwan J, Sharpe M. Fear of recurrence and beliefs about preventing recurrence in persons who have suffered a stroke. J Psychosom Res 2006;61:747–55

- Becker G, Kaufman S. Managing an uncertain illness trajectory in old age: patients’ and physicians’ views on stroke. Med Anthropol Q 1995;9:165–87

- Norris M, Kilbride C. From dictatorship to a reluctant democracy: stroke therapists talking about self-management. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:32–8

- Scheppers E, van Dongen E, Dekker J, et al. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: a review. Fam Pract 2006;23:325–48

- Strudwick A, Morris R. A qualitative study exploring the experiences of African-Caribbean informal stroke carers in the UK. Clin Rehabil 2010;24:159–67

- Protheroe J, Rogers A, Kennedy A, et al. Promoting patient engagement with self-management support information: a qualitative meta-synthesis of processes influencing uptake. Implement Sci 2008;3:44. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-44

- Williams G. The genesis of chronic illness: narrative re-construction. Sociol Health Illn 1984;6:175–200

- Yamey G, Greenwood R. Religious views of the ‘medical’ rehabilitation model: a pilot qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2004;26:455–62

- Norris M, Allotey P, Barrett G. ‘It burdens me’: the impact of stroke in central Aceh, Indonesia. Sociol Health Illn 2012;34:826–40

- Ypinazar V, Margolis S. Delivering culturally sensitive care: the perceptions of older Arabian Gulf Arabs concerning religion, health, and disease. Qual Health Res 2006;16:773–87

- Johnston B, Glass B, Oliver R. Religion and disability: clinical research and training considerations for rehabilitation professional. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:1153–63

- Ljungberg C, Hanson E, Lövgren M. A home rehabilitation program for stroke patients: a pilot study. Scand J Caring Sci 2001;15:44–53

- Brashler R. Ethics, family givers and stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2006;13:11–17

- Schiøtz M, Bøgelund M, Almdal T, et al. Social support and self-management behaviour among patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2012;29:654–61

- Jonsdottir H. Self-management programmes for people living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a call for a reconceptualisation. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:621–37

- Nazroo J, Williams D. The social determination of ethnic/racial inequalities in health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson RG, eds. The social determinants of health. Oxford: University Press; 2005

- Bhopal R, Hayes L, White M, et al. Ethnic and socio-economic inequalities in coronary heart disease, diabetes and risk factors in Europeans and South Asians. J Publ Health 2002;24:95–105