Abstract

In healthy participants, cortisol administration has been found to impair autobiographic memory retrieval. We recently reported that administration of 10 mg of hydrocortisone had enhancing effects on autobiographical memory retrieval, i.e. more specific memory retrieval, in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while in healthy controls the impairing effects were replicated. We here report a re-analysis of these data with respect to cue-word valence and retrieval time. In a placebo-controlled cross-over study, 43 patients with PTSD and 43 age- and sex-matched healthy controls received either placebo or hydrocortisone orally before the autobiographical memory test was performed. We found that the effects of cortisol on memory retrieval depended on cue-word valence and group (significant interaction effects of drug by group and drug by valence by group). The enhancing effect of cortisol on memory retrieval in PTSD seemed to be relatively independent of cue-word valence, while in the control group the impairing effects of cortisol were only seen in response to neutral cue-words. The second result of the study was that in patients as well as in controls, cortisol administration led to faster memory retrieval compared to placebo. This was seen in response to positive and (to lesser extend) to neutral cue-words, but not in response to negative cue-words. Our findings illustrate that the opposing effects of cortisol on autobiographical memory retrieval in PTSD patients and controls are further modulated by the emotionality of the cue-words.

Introduction

Alterations of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, e.g. reduced basal cortisol levels and enhanced feedback sensitivity, are often reported in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) patients. These findings have been interpreted in the context of enhanced glucocorticoid receptor (GR) sensitivity (Rohleder et al., Citation2010; Yehuda, Citation2009). However, there are also contradictory findings (Meewisse et al., Citation2007).

Glucocorticoids have substantial influence on cognition. In healthy humans, most studies suggest impairing effects of glucocorticoids on memory retrieval, especially hippocampus-based declarative memory retrieval, while memory consolidation seems to be improved by glucocorticoids (Wolf, Citation2009). Relatively few studies have investigated the effects of cortisol administration on memory in PTSD patients, and these have yielded inconclusive results (Bremner et al., Citation2004; Grossman et al., Citation2006; Yehuda et al., Citation2007, Citation2010). In a recent study, our group found that cortisol has enhancing, rather than impairing effects on memory retrieval in PTSD patients (Wingenfeld et al., Citation2012). This effect was observed in a word list-learning paradigm and in an autobiographical memory test (AMT). Several studies indicate that PTSD patients have deficits in the AMT, e.g. over-generalized autobiographical memory retrieval (Williams et al., Citation2007). Patients with over-generalized memory have difficulties in retrieving specific autobiographical events; instead, they tend to reply with abstract or general memory content (e.g. they summarize several different events).

There are two other studies documenting impaired memory specificity after cortisol in healthy participants, but it is not clear whether valence of word stimuli influences this effect (Buss et al., Citation2004; Young et al., Citation2011). However, when using word lists, the effect of cortisol on declarative memory retrieval is stronger for emotional than neutral stimuli (Wolf, Citation2009). Thus, the valence of stimuli used in memory tasks seems to have an important impact on the effects of glucocorticoid on memory performance in healthy participants. In psychiatric patients, the interaction between cortisol effect on memory and stimuli valence has not been sufficiently addressed.

In a previous study, we investigated the effects of hydrocortisone on reaction times in a response inhibition task. Healthy participants, but not patients with major depressive disorder, have faster reaction times in an emotional go/no-go task after hydrocortisone compared to placebo (Schlosser et al., Citation2013). Interestingly, this effect was predominantly seen when the participants had to respond to neutral targets. Other studies reported similar (as well as contrary) results (Oei et al., Citation2009; Scholz et al., Citation2009). In memory tasks, time until memory retrieval has not been investigated in detail. However, it is reported that hydrocortisone slows response times for categorical memories in an AMT (Young et al., Citation2011). The retardation in response time is only observed using a relatively high dosage of hydrocortisone. Reaction time for specific memories was not affected. Again, no study investigated the effect of cortisol on time until memory retrieval using an autobiographic memory test in patients suffering from PTSD.

The aim of the current study was to reanalyze our data concerning the effects of cortisol administration on autobiographical memory retrieval in PTSD patients compared to healthy controls (Wingenfeld et al., Citation2012) with respect to two questions: (1) does the valence of the cue-words used in the AMT affect the results? (2) Is the time the participants need to retrieve an autobiographic memory affected by cortisol administration?

Methods and materials

The data of 43 patients with PTSD and 43 age- and sex-matched healthy controls were analyzed in this study. Mean age was 31.24 (9.7) years ranged between 18 and 57. Six participants in each group were male. Participants were excluded if they had any current or previous severe medical illnesses. Further exclusion criteria were pregnancy, current anorexia, current or lifetime schizophrenia, alcohol or drug dependence, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, major depression with psychotic symptoms or cognitive impairment. Intake of antidepressants did not lead to exclusion.

Patients were recruited at the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy Bethel (Ev. Hospital Bielefeld, Germany), and at the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf & Schön Klinik Hamburg-Eilbek, Germany. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Healthy participants were recruited by local advertisement and received financial remuneration for their efforts (100€). The study was approved by the University of Muenster Ethics Committee and the Ethics Committee of the Medical Council of Hamburg.

To assess psychiatric diagnoses, participants were interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I. PTSD symptoms (patients only) were also assessed with the post-traumatic stress diagnostic scale (PDS). Depressive mood state was measured in all participants using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

In a placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over study, each participant was tested twice with parallel versions of the AMT (see below). The two versions of the tests were counterbalanced across the two test conditions. Thirty minutes after administration of 10 mg hydrocortisone (Jenapharm®, Jena, Germany) or placebo the AMT was performed. The same procedure with the alternate test condition was repeated after one week.

A modified version of the AMT (Buss et al., Citation2004) was applied. After an initial practice on one cue-word, the participants were instructed to write down a specific event from their past in response to six adjectives which were consecutively presented on cards. The AMT consists of two neutral, positive and negative cue-words, respectively. Participants were instructed to recall events that had happened at least one day prior to testing, that had taken place at a certain time and place and did not last any longer than one day. They were also instructed to describe individuals and specific activities involved in the event. The specificity of the answers was evaluated by two trained raters, separately. An answer was considered specific when at least three of the following criteria were met: description of the location, time and persons involved and activities carried out. Each specific answer was given a score of 1 and non-specific answers a score of 0 (Wingenfeld et al., Citation2012). Thus, with six adjective presented in this test, the maximum number of specific events retrieved is six. The response time was recorded with a stopwatch beginning when the cue word was presented. The response time was defined as the latency to the first written word of each response (Young et al., Citation2011). Maximum time was 60 s to retrieve an autobiographical event, i.e. after 60 s the next cue-word was presented.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Demographic data were analyzed using Student’s t test for continuous data. Data from the AMT were analyzed using ANOVA. In case of post hoc analyses, Bonferroni's correction procedure was used.

Results

Patients with PTSD and healthy controls were comparable in age (tdf84 = −0.122, p = 0.79). As expected, PTSD patients reported more depressive symptoms (BDI mean: PTSD 25.9 (8.7), controls 2.5 (3.3), tdf82 = 16.271, p < 0.001). Mean PDS score, measuring PTSD symptom severity, was 31.3 (8.7, range 13–47) in the patients group, reflecting a moderate to severe PTSD symptomatology. For a more detailed description of the study group see also Wingenfeld et al. (Citation2012).

AMT: valence of word stimuli

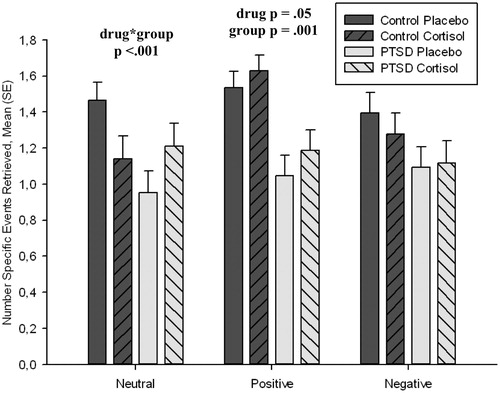

A 2 × 2 × 3 ANOVA with repeated measures was conducted with the main factors drug condition, group and cue-word valence. There was a significant effect of the main effect of group (F1,84 = 6.441, p = 0.013), reflecting less specific memory retrieval in the PTSD group. Furthermore, analyses revealed a significant drug by group interaction effect (F1,84 = 10.013, p = 0.002), a non-significant valence effect (F2,168 = 2.894, p = 0.058) and a significant three way drug by group by valence interaction effect (F2,168 = 4.442, p = 0.013). The results are presented in .

Figure 1. Memory specificity, i.e. number of specific memories retrieved (out of six cue-words, two of each valence) in response to neutral, positive and negative cue-words after placebo and hydrocortisone. There was a significant group by drug condition interaction effect (p = 0.002) and a group by drug condition by valence interaction effect. In the PTSD group there was an effect of drug condition (p = 0.01) but no valence effect, while in the control group there was a drug by valence interaction found, showing that the impairing effect of hydrocortisone on memory primarily affect responses to neutral cue-words (further details on statistical analysis, see Results section).

We re-ran all analyses with BDI scores as covariate, but did not find a main effect of depression or BDI by valence or BDI by drug interaction effect. Furthermore, when adding sex as an additional factor in the analyses, neither a significant main effect of sex nor any significant sex related interaction effect was found.

To specify the interaction effects, we first conducted two 2 × 3 ANOVAs for each group separately. In the PTSD group, we found a significant drug effect (F1,42 = 7.114, p = 0.01) but no main effect of valence (p = 0.94) or drug by valence interaction effect (p = 0.29). Thus, hydrocortisone positively affects memory retrieval independent of word valence.

In the control group, there was a trend towards a main effect of drug (F1,42 = 3.558, p = 0.066), a significant main effect of valence (F2,84 = 5.007, p = 0.009) and a significant drug by valence interaction effect (F2,84 = 5.882, p = 0.004). These results indicate that in the control group the effect of hydrocortisone on memory specificity differs with respect to cue-word valence. Post hoc paired sample t tests revealed that the impairing effects of hydrocortisone on memory were only seen in response to neutral cue-words (t42 = 2.988, p = 0.005 (significance level p = 0.01 due to alpha error correction)) but not to positive (p = 0.21) and negative (p = 0.22) cue-words, respectively.

Furthermore, we conducted separate 2 × 2 ANOVAs for each valence. For neutral cue-words, we found a significant drug by group interaction effect (F1,84 = 13.993, p < 0.001), but no main effect of group or drug condition. For positive cue-words, there was a significant effect of drug condition (F1,84 = 3.940, p = 0.05) and a significant group effect (F1,84 = 12.065, p = 0.001). For negative cue-words no significant effect could be shown.

AMT: time until memory retrieval

There were data concerning time until memory retrieval for 39 PTSD patients and 42 controls. When analyzing response time (considering cue-word valence) in a 2 × 2 × 3 ANOVA, we found a significant effect of drug (F1,75 = 4.234, p = 0.043). Furthermore, an effect of cue-word valence (F2,150 = 5.539, p < 0.005) and a drug by cue-word valence interaction effect (F2,150 = 3.934, p = 0.022) were revealed. The drug by group interaction (p = 0.28) and the cue-word valence by group (p = 0.44) interaction failed significance, as well as the drug by cue-word valence by group interaction (p = 0.16) and the main effect of group (p = 0.57). The results are presented in .

Table 1. Time (mean seconds/SD) until memory retrieval in the AMT in patients with PTSD and healthy controls.

Again, there was no significant main effect of sex or drug by sex interaction effect. Depression scores (BDI as covariate) did not influence the results.

To specify the source of the drug by valence interaction effect, we performed paired sample t tests for each valence (over both groups). The positive effect of hydrocortisone on response time was seen in response to positive cue-words (t78 = 2.728, p = 0.008), but not in response to neutral cue-words (note strong trend) (t78 = 2.299, p = 0.024 (significance level p = 0.01 due to alpha error correction)) or negative cue-words (p = 0.34).

Furthermore, we analyzed the valence effect more detailed again using paired sample t tests (over both groups and over both drug conditions). We found a significant difference between reaction time to neutral compared to negative cue words (t80 = − 2.759, p = 0.007 (significance level p = 0.01 due to alpha error correction)). The comparison between reaction times to neutral and positive (p = 0.57) as well as between positive and negative cue-words (p = 0.43), respectively, failed to reach statistical significance.

We also analyzed whether the response times differed between specific and non-specific memories. The 2 × 2 ANOVA (response time specific memory versus response time non-specific memory × healthy controls versus PTSD patients) revealed no significant main or interaction effect, either for the placebo or the cortisol condition (all ps > 0.40).

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to analyze whether cue-word valence influences the effects of cortisol on autobiographic memory retrieval in patients with PTSD and healthy controls. We found that hydrocortisone enhanced memory retrieval in PTSD relatively independent of word-cue valence. In the control group, memory retrieval was less specific after hydrocortisone compared to placebo, but this was seen predominantly in response to neutral cue-words.

Both groups showed faster retrieval responses for autobiographic events after hydrocortisone compared to placebo. However, these effects were only seen to positive cue-words and to a lesser extent for neutral cue-words. Effects on reaction time occurred regardless of whether a retrieved memory was specific or not.

Effects of hydrocortisone on memory retrieval – the impact of valence

Prior studies found that the effects of cortisol on memory are most pronounced for emotional stimuli (Wolf, Citation2008). Relatively few studies have tested effects of cortisol on autobiographical memory. One study in healthy participants found that the impairing effects of cortisol administration on memory were strongest in response to neutral cue-words (Buss et al., Citation2004). This is in line with our current findings, but contrasts with findings in other declarative memory tests. Furthermore, the cortisol increase after psychosocial stress is related to less specific autobiographic memory retrieval elicited by neutral but not negative cue-words (Tollenaar et al., Citation2009), which fits to our data as well. However, other studies do not find significant influence of stimuli valence on performance (Young et al., Citation2011). In sum, there is some evidence for stronger impairing cortisol effect on autobiographical memory retrieval when neutral stimuli are used, while the effect seems to be less pronounced to negative stimuli. Possibly, the consolidation of autobiographic events with emotional impact is stronger and thus less susceptible to the impairing effects of cortisol on retrieval. It is of note that the effects of cortisol on autobiographic memory retrieval appear to differ with respect to the influence of valence/arousal compared with studies of declarative (words, pictures, etc.) retrieval.

Effects of hydrocortisone on memory retrieval – response time

Only one prior study has investigated time until memory retrieval in an AMT. Contrary to our results, it was shown that hydrocortisone slowed response times for categorical memories (Young et al., Citation2011), but only when using a relatively high dosage of hydrocortisone (i.e. 0.45 mg/kg). Reaction time for specific memories was not influenced. Speed is typically not an outcome measure in declarative memory tasks, so relatively little data on modulation by cortisol is available. It might be helpful to look at other neuropsychological domains. In one of our studies, we investigated the effects of hydrocortisone on reaction times in a response inhibition task. Healthy participants, but not patients with major depressive disorder, showed faster reaction times in an emotional go/no-go task after hydrocortisone compared to placebo (Schlosser et al., Citation2013). Interestingly, this effect was predominantly seen when the participants had to respond to neutral targets. Other studies reported similar results concerning cortisol and stress effects on reaction time or task speed mostly using working memory tests, but there also contrary results (Oei et al., Citation2009; Otte et al., Citation2007; Scholz et al., Citation2009; Wingenfeld et al., Citation2011).

An integrated interpretation of the observations made in our healthy control group has to address the issue that cortisol impaired autobiographic memory retrieval specificity (especially for neutral cue words) while at the same time increasing retrieval speed. In line with human neuroimaging evidence, we suggest that the reduced autobiographic memory specificity reflects impairing effects of hydrocortisone on hippocampal based recollection processes (de Quervain et al., Citation2003; Oei et al., Citation2007). As a compensatory mechanism, retrieval might rely more on perirhinal and parahippocampal based familiarity processes (Aggleton & Brown, Citation2006). These are known to be faster but less specific (Koen & Yonelinas, Citation2011). However, these interpretations are somewhat speculative and require empirical testing.

Effects of hydrocortisone on memory retrieval – differences between PTSD patients and healthy controls

The effects of cortisol on memory retrieval differed in PTSD patients and controls. Overall, in PTSD cortisol enhanced the specificity of the autobiographical episodes. As we discussed, this in our former paper (Wingenfeld et al., Citation2012), we will only briefly rely comment on this finding.

There is considerable evidence for structural and functional abnormalities in the hippocampus in PTSD patients (Karl et al., Citation2006). This might underlie their reduced autobiographic memory specificity (Williams et al., Citation2007). In those patients, a cortisol induced shift towards non-hippocampal based memory retrieval processes might rescue performance, at least in part. Similar compensatory shifts between multiple memory systems have been observed in rodents and humans (Schwabe & Wolf, Citation2012). Interestingly, patients and controls differ substantially in autobiographic memory performance under placebo conditions, possibly reflecting differences in hippocampal integrity. In contrast, after hydrocortisone administration, the difference between the two groups disappeared, which could reflect a similar functioning of the perirhinal/parahippocampal familiarity system in both groups.

In terms of PTSD psychopathology, i.e. involuntary memory retrieval (intrusions, flashbacks), one might speculate that hydrocortisone reduces these kind of autobiographic memory retrieval, as suggested by some studies (de Quervain, Citation2006), providing resources for “normal” cognitive functions. Another prominent symptom in PSTD is chronic hyperarousal. In this context exogenous cortisol might dampen HPA axis activity by inhibiting central CRH release (as discussed by Yehuda et al., Citation2007), thus improving cognitive function.

However, alternative explanations cannot be ruled out. These could consist of a cortisol-induced enhancement of hippocampal functioning in PTSD patients (Wingenfeld et al., Citation2012). This interpretation would be in line with a recent neuroimaging study (Yehuda et al., Citation2010), as well as with a recent rodent study investigating the impact of early life stress on hippocampal plasticity in adulthood (Champagne et al., Citation2008).

Functional imaging studies performed in PTSD patients typically investigate the neural correlates of traumatic memories, which represent a specific form of autobiographical memory. The data suggest that PTSD memory impairments are associated with decreased cerebral blood flow and a failure of activation in the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex, along with increased blood flow in the amygdala (Bremner, Citation2007). Interestingly, a correlation between increased amygdala activation and decreased activation in prefrontal areas during traumatic memories has been reported (Shin et al., Citation2004). Overall, an enhanced responsiveness of the amygdala during stress, i.e. symptom provocation or remembering traumatic experiences, in concert with disturbances of hippocampal and prefrontal areas (hypofunction), seem to be consistent findings in PTSD (Shin et al., Citation2006). Of note, the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are essential for memory processes. In accordance with the studies of Yehuda et al. (Citation2010), Champagne et al. (Citation2008) and our own data, one might suggest that a low dose of hydrocortisone helps re-connect this neural network, resulting in enhanced memory retrieval. Possibly, the hippocampal feedback on the stress regulatory systems is strengthened or mimicked through cortisol promoting the capacity for cognitive functions. Enhanced memory specificity in PTSD patients may also be interpreted in terms of altered GR functioning (Rohleder et al., Citation2010; Yehuda, Citation2009), possibly as a result of early adverse experiences (McGowan et al., Citation2009). However, the neural underpinnings of “ordinary” autobiographic memories as well as the effects of stress or cortisol on autobiographic memories have not been investigated sufficiently in PTSD patients. In this context, more imaging studies are needed.

In conclusion, the current results indicate that the cortisol-induced effects on autobiographical memory retrieval are influenced by the valence of the stimuli used. The opposing effects of cortisol on memory specificity in PTSD patients compared to healthy controls are predominantly seen to neutral cue-words. Furthermore, we provided evidence for an effect of cortisol administration on retrieval time of autobiographical memories that is dependent on valence. These results need to be replicated and the underlying neuronal correlates should be investigated using functional imaging techniques.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

The study was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (WI 3396/1-awarded to KW, OTW and MD).

References

- Aggleton JP, Brown MW. (2006). Interleaving brain systems for episodic and recognition memory. Trends Cogn Sci 10:455–63

- Bremner JD. (2007). Neuroimaging in posttraumatic stress disorder and other stress-related disorders. Neuroimag Clin N Am 17:523–38, ix

- Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Vermetten E, Afzal N, Nazeer A, Newcomer JW, Charney DS. (2004). Effects of dexamethasone on declarative memory function in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 129:1–10

- Buss C, Wolf OT, Witt J, Hellhammer DH. (2004). Autobiographic memory impairment following acute cortisol administration. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29:1093–6

- Champagne DL, Bagot RC, van Hasselt F, Ramakers G, Meaney MJ, de Kloet ER, Joels M, Krugers H. (2008). Maternal care and hippocampal plasticity: evidence for experience-dependent structural plasticity, altered synaptic functioning, and differential responsiveness to glucocorticoids and stress. J Neurosci 28:6037–45

- de Quervain DJ. (2006). Glucocorticoid-induced inhibition of memory retrieval: implications for posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1071:216–20

- de Quervain DJ, Henke K, Aerni A, Treyer V, McGaugh JL, Berthold T, Nitsch RM, et al. (2003). Glucocorticoid-induced impairment of declarative memory retrieval is associated with reduced blood flow in the medial temporal lobe. Eur J Neurosci 17:1296–302

- Grossman R, Yehuda R, Golier J, McEwen B, Harvey P, Maria NS. (2006). Cognitive effects of intravenous hydrocortisone in subjects with PTSD and healthy control subjects. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1071:410–21

- Karl A, Schaefer M, Malta LS, Dorfel D, Rohleder N, Werner A. (2006). A meta-analysis of structural brain abnormalities in PTSD. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30:1004–31

- Koen JD, Yonelinas AP. (2011). From humans to rats and back again: bridging the divide between human and animal studies of recognition memory with receiver operating characteristics. Learn Mem 18:519–22

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D'Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ. (2009). Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci 12:342–8

- Meewisse ML, Reitsma JB, de Vries GJ, Gersons BP, Olff M. (2007). Cortisol and post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 191:387–92

- Oei NY, Elzinga BM, Wolf OT, de Ruiter MB, Damoiseaux JS, Kuijer JP, Veltman DJ, et al. (2007). Glucocorticoids decrease hippocampal and prefrontal activation during declarative memory retrieval in young men. Brain Imag Behav 1:31–41

- Oei NY, Tollenaar MS, Spinhoven P, Elzinga BM. (2009). Hydrocortisone reduces emotional distracter interference in working memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34:1284–93

- Otte C, Moritz S, Yassouridis A, Koop M, Madrischewski AM, Wiedemann K, Kellner M. (2007). Blockade of the mineralocorticoid receptor in healthy men: effects on experimentally induced panic symptoms, stress hormones, and cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology 32:232–8

- Rohleder N, Wolf JM, Wolf OT. (2010). Glucocorticoid sensitivity of cognitive and inflammatory processes in depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:104–14

- Schlosser N, Wolf OT, Fernando SC, Terfehr K, Otte C, Spitzer C, Beblo T, et al. (2013). Effects of acute cortisol administration on response inhibition in patients with major depression and healthy controls. Psychiatry Res [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.12.019

- Scholz U, La Marca R, Nater UM, Aberle I, Ehlert U, Hornung R, Martin M, Kliegel M. (2009). Go no-go performance under psychosocial stress: beneficial effects of implementation intentions. Neurobiol Learn Mem 91:89–92

- Schwabe L, Wolf OT. (2012). Stress modulates the engagement of multiple memory systems in classification learning. J Neurosci 32:11042–9

- Shin LM, Orr SP, Carson MA, Rauch SL, Macklin ML, Lasko NB, Peters PM, et al. (2004). Regional cerebral blood flow in the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex during traumatic imagery in male and female Vietnam veterans with PTSD. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:168–76

- Shin LM, Rauch SL, Pitman RK. (2006). Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1071:67–79

- Tollenaar MS, Elzinga BM, Spinhoven P, Everaerd W. (2009). Autobiographical memory after acute stress in healthy young men. Memory (Hove, England) 17:301–10

- Williams JM, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Herman D, Raes F, Watkins E, Dalgleish T. (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychol Bull 133:122–48

- Wingenfeld K, Driessen M, Terfehr K, Schlosser N, Fernando SC, Otte C, Beblo T, et al. (2012). Cortisol has enhancing, rather than impairing effects on memory retrieval in PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37:1048–56

- Wingenfeld K, Wolf S, Krieg JC, Lautenbacher S. (2011). Working memory performance and cognitive flexibility after dexamethasone or hydrocortisone administration in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 217:323–9

- Wolf OT. (2008). The influence of stress hormones on emotional memory: relevance for psychopathology. Acta Psychol 127:513–31

- Wolf OT. (2009). Stress and memory in humans: twelve years of progress? Brain Res 1293:142–54

- Yehuda R. (2009). Status of glucocorticoid alterations in post-traumatic stress disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1179:56–69

- Yehuda R, Golier JA, Bierer LM, Mikhno A, Pratchett LC, Burton CL, Makotkine I, et al. (2010). Hydrocortisone responsiveness in Gulf War veterans with PTSD: effects on ACTH, declarative memory hippocampal [(18)F]FDG uptake on PET. Psychiatry Res 184:117–27

- Yehuda R, Harvey PD, Buchsbaum M, Tischler L, Schmeidler J. (2007). Enhanced effects of cortisol administration on episodic and working memory in aging veterans with PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 32:2581–91

- Young K, Drevets WC, Schulkin J, Erickson K. (2011). Dose-dependent effects of hydrocortisone infusion on autobiographical memory recall. Behav Neurosci 125:735–41