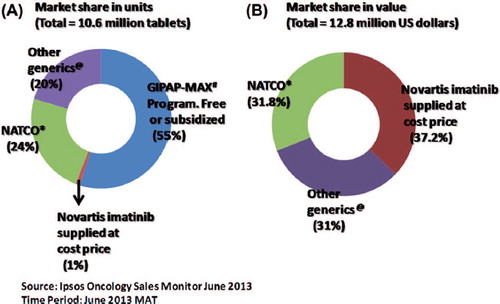

The importance of generic pharmaceutical agents in increasing access to and reducing the cost of medical therapy is widely acknowledged, even in developed countries [Citation1,Citation2]. This is especially relevant for cancer in developing economies and countries where there is an absence of health insurance or a predominantly self-pay system. It is estimated that with the use of generic chemotherapy drugs in India, a country that fulfills the above criteria, the annual saving is approximately US$ 843 million [Citation3]. The impact of the cost of generics versus innovator molecules of imatinib in the Indian market is illustrated in . While 55% of diagnosed patients receive the innovator molecule from the GIPAP (The Glivec® International Patient Assistance Program) and Max foundation, either free or at subsidized cost (details of costing not available), the remaining patients purchase the drug at the market rate. Among the 45% of patients for whom the drug is supplied at the market rate, the innovator molecule accounts for 1% in units supplied, but 37.2% of the market share in actual revenue generated per year (Ipsos Research Pvt. Ltd., Syndicated Oncology Sales Monitor, India).

Figure 1. (A) Market share of imatinib units/year (tablets), includes GIPAP-Max program which is supplied either free of cost or at subsidized rates. (B) Market share in US dollars/year, excludes GIPAP-Max program and only considers units sold at market rates. #GIPAP-MAX foundation: The Glivec® International Patient Assistance Program and Max foundation. *NATCO: NATCO Pharma Ltd., India (manufacturer of Veenat, a generic brand of imatinib). @Other generics: refers here to 23 other pharmaceutical companies that market generic imatinib in India (all < 2% of the market share).

The use of generics is invariably associated with controversies regarding intellectual patent protection, which defines the fair pricing, quality and efficacy of generic molecules. While these debates have been going on for decades, the recent high-profile court rulings with regard to patent protection and generic imatinib that have gone against large multinational pharmaceutical companies (MNPCs) have re-ignited these discourses [Citation4]. Overall these court rulings have been welcomed in academic circles [Citation5] and by patient advocacy groups. Large MNPCs have, as expected, voiced their concerns over these court decisions. The role played by MNPCs in drug pricing, and in molding and influencing academic and physician opinions and preferences, manipulating legal systems and even governments and drug approval agencies, has been widely commented on, and is best summarized in an article written by Arnold S. Relman and Marcia Angell for The New Republic in 2002, which is very much relevant even today [Citation6]. In this commentary we restrict the discussion to addressing the issue of the quality and efficacy of generic imatinib.

In this issue of the journal there are two articles that highlight the concern of decreased efficacy and increased toxicity of generic imatinib in comparison to the innovator brand. Saavedra and Vizcarra [Citation7] from Colombia and Alwan et al. [Citation8] from Iraq describe their experience in 12 and 126 patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) who received generic imatinib, respectively. In the study by Alwan et al., all patients initially received the innovator molecule and were subsequently switched to the generic molecule, while a similar switch happened in eight of the 12 patients in the study by Saveedra and Vizcarra (the remaining four were on generic imatinib from the start). In the study by Alwan et al., patients were on the innovator molecule for a median duration of 4 years (range: 0.5–7) prior to switching to the generic brand. Following the switch to a generic brand, 17.5% lost complete hematological response (CHR), while in 17.5% there was disease progression within 3 months. This was also associated with a high proportion of patients developing toxicity, although the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grade of the toxicity is not given. On switching back to the innovator molecule, in approximately 8% CHR was restored. In the report by Saveedra and Vizcarra, of the four patients who received a generic brand from the start, only one patient showed evidence of a response to therapy and all had significant adverse effects. Of the eight patients who were switched to generic brands there was loss of cytogenetic (CTG) response or rising transcript levels in five patients within 3–4 months of the switch; all patients, for these reasons or intolerance to the generic brand, were subsequently switched to second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). All eight patients have remained on second-generation TKIs and have regained CTG response. Saveedra and Vizcarra declare that their research was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation [Citation7]; Alwan et al. declare that they received financial support for editorial assistance from the same company [Citation8].

These two articles highlight the concerns with generic imatinib. However, one has to wonder whether this is truly reflective of worldwide experience with generic imatinib. When one considers a generic molecule, potential differences can arise from the formulation (pills versus syrup versus intravenous preparation), the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and the excipients used to stabilize or bulk the final product prior to formulation. In the case of imatinib the formulation is the same for the innovator and the generics (pills). The API in imatinib can be in three polymorphic forms (α, β or γ). The innovator molecule is the β-crystal form while the majority of generics have the α-crystal form. In spite of the initial suggestion and claim that the β-crystal form was superior, the overall consensus is that there is no difference in efficacy, water solubility and absorption of either crystal form [Citation9]. Variation in excipients could potentially alter bioavailability, and hence bioequivalence studies are required by agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that are involved in approval and licensing of generic molecules, although the theoretical potential impact of these variations in excipients on short- and long-term toxicity is not addressed by such studies. The Hatch-Waxman Amendments to Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act Section 505(j) 21 U.S.C-1984 was considered a landmark legislation that facilitated the generic pharmaceutical industry and allowed them to rely on findings of safety and efficacy of innovator drugs after expiration of patents and exclusivities. More significantly it did not require them to repeat expensive clinical and preclinical trials with the generic molecule. Generic imatinib has been approved by Canada and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) after fulfilling bioequivalence criteria.

There have been numerous anecdotal reports of a lack of efficacy of generic imatinib, although most of these reports are limited by the small numbers of patients. Of some concern is that a number of these publications have a conflict of interest by being funded in part by the innovator MNPCs. There is also a publication bias in that an article with lack of response in a small subset/cohort being reported is more likely to be published than a similar size subset/cohort where there is appropriate response. However, one should not and cannot discount these reports, and the onus should be placed on the generic manufacturers to appropriately address these issues. While MNPCs have engendered significant criticism over pricing and evergreening of patents, for example, there have not been significant concerns about the quality of their products. It is also important to recognize and acknowledge that the generic pharmaceutical industry is not in this business for charity. Like MNPCs they are primarily in the business for profit, and are answerable to the shareholders of their companies. The abbreviated new drug approval (ANDA) as a result of the Hatch-Waxman Amendments does not require the generic pharmaceutical industry to conduct clinical trials prior to approval. However, it would be reasonable to expect them to compulsorily report phase IV study data post-marketing and have a sample size for such a study to make reasonable comparison with the reported phase III study of the innovator. Reporting of post-marketing data is at present not a requirement by any approval agency in the world. It would have been ideal to have a direct clinical trial in comparison with the innovator molecule; however, the costing of the innovator molecule is such that it prevents one from comparing it to cheaper alternatives in a clinical trial setting, and serves to protect the innovator from less expensive alternatives [Citation10]. The generic pharmaceutical industry is also driven by profit, and they often operate in countries with lower standards and an absence of systems in place to approve and monitor the quality of marketed generic drugs. These countries are especially vulnerable to fraudulent practices, as has been illustrated by some recent high-profile cases [Citation11]. In spite of these concerns, the overwhelming majority of physicians and academic institutions believe that generic drugs, including imatinib, are as efficacious as the innovator molecules. In this issue of the journal there is another article by Eskazan et al. [Citation12], which also compares the impact of switching patients to generic imatinib. In this report on 145 patients, 65 were continued on the innovator molecule while 76 were switched to a generic brand of imatinib after a median period of 55 months (range: 3–126) and four were on generic brands from the time of diagnosis. At a median follow-up of 12 months (range: 4–16) post-switching to a generic brand, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of maintenance of response state, achievement of greater depth of response, progression of disease and adverse events. Eskazan et al. do not report any conflict of interest. Similar to this report and in response to an article addressing the price of drugs in CML [Citation2] there were 12 responses, of which four addressed the issue of efficacy (one from Turkey, one from Mexico, two from India), and all of them stated that they did not find any difference in response or toxicity between the generic and the innovator molecule. A more recent article considering plasma trough levels and response in patients on imatinib did not find any difference between the generic and the innovator molecule [Citation13].

The majority of physicians involved in the treatment of CML in India, including the author, do not find a significant difference between generic and innovator imatinib, and numerous articles on this topic have been reported in local Indian journals. In the presence of so many generic brands and an absence of genuine scientific comparison, the choice between the generics in India is based on a combination of locally circulated expert opinions, reputation of the company involved, availability of bioequivalence data and personal experience.

It would have been very useful if we had had pharmacokinetics data available for the patients in the two studies in this issue that reported reduced efficacy and increased toxicity, or if the tablets (manufacturing lot) that were used in these patients had been subjected to scientific analysis for content and bioequivalence. Even in the absence of these, the articles reported in this issue highlight the need for greater regulation and oversight of generic molecules being introduced in different health care systems, and the need for processes to be put in place to monitor therapy when such changes are made. This is even more relevant in countries where mechanisms of approval and continued monitoring of the quality of the generic drugs being supplied are not well established.

Supplementary Material

Download Zip (489.8 KB)Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at www.informahealthcare.com/lal.

References

- Kerr D. Generic drugs: their role in better value cancer care. Ann Oncol 2013;24(Suppl. 5):v5.

- Experts in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. The price of drugs for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a reflection of the unsustainable prices of cancer drugs: from the perspective of a large group of CML experts. Blood 2013;121:4439–4442.

- Lopes Gde L. Cost comparison and economic implications of commonly used originator and generic chemotherapy drugs in India. Ann Oncol 2013;24(Suppl. 5):v13–v16.

- Chatterjee P. India's patent case victory rattles Big Pharma. Lancet 2013;381:1263.

- Kapczynski A. Engineered in India–patent law 2.0. N Engl J Med 2013;369:497–499.

- Relman AS, Angell M. America's other drug problem. New Republ 2002;Dec 16:27–41. Available from: www.newrepublic.com/article/americas-other-drug-problem

- Saavedra D, Vizcarra F. Deleterious effects of non-branded versions of imatinib used for the treatment of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: a case series on an escalating issue impacting patient safety. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55;2813–2816.

- Alwan AF, Matti BF, Naji AS, et al. Prospective single-center study of chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: switching from branded imatinib to a copy drug and back. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:2830–2834.

- Generic imatinib. BC Cancer Agency provincial systemic therapy update. 2013;16:1–2. Available from: www.bccancer.bc.ca/NR/rdonlyres/6689653F-6689620F6689655-6684882-A6689659AA-6689656F6689690F6689657EA6689394/6666704/STUpdateOctober6682013_FINAL.pdf

- Mailankody S, Prasad V. Comparative effectiveness questions in oncology. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1478–1481.

- Kay M. Indian generics manufacturer Ranbaxy agrees to pay $500m to settle US fraud and drug safety charges. BMJ 2013;346:f3536.

- Eskazan AE, Elverdi T, Yalniz FF, et al. The efficacy of generic formulations of imatinib mesylate in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:2935–2937.

- Malhotra H, Sharma P, Bhargava S, et al. Correlation of plasma trough levels of imatinib with molecular response in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:2614–2619.