Abstract

Although mental disorders are a major public health problem, the development of mental health services has been a low priority everywhere, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Recent years have seen a growing understanding of the importance of population mental health and increased attention to the need to develop mental health systems for responding to population mental health service needs. In countries and regions where mental health services are all but nonexistent, and in postconflict and postdisaster settings, there are many impediments to establishing or scaling up mental health services. It is frequently necessary to act simultaneously on multiple fronts: generating local evidence that will inform decision makers; developing a policy framework; securing investment; determining the most appropriate service model for the context; training and supporting mental health workers; establishing or expanding existing services; putting in place systems for monitoring and evaluation; and strengthening leadership and governance capabilities. This article presents the approach of the Centre for International Mental Health in the Melbourne School of Population Health to mental health system development, and illustrates the way in which the elements of the program are integrated by giving a brief case example from Sri Lanka.

Mental disorders are a major public health problem, and the biggest public health problem among young people in the most productive years of life. Taken together, the high prevalence of mental disorders,Citation1 the annual loss of life from suicide (>300,000/year in Asia,Citation2 the most common cause of death among young adults), the decreased longevity of people with schizophrenia (life expectancy 15–20 years less than the general population), the high disability burden attributable to mental disorders (>30% of all disability-adjusted life years from noncommunicable diseases),Citation3 the massive loss of economic productivity, and the abject povertyCitation4 and misery of so many people with mental disorders (most of whom have no access to treatment and care in low- and middle-income countries (LAMICs)) suggest the dimensions of the problem. And yet mental illness, along with the health systems that need to be developed to provide adequate treatment and care and to improve population mental health, has been largely ignored by governments, bilateral aid agencies, other major development funders, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) promoting international development, researchers, and educators.Citation5

The key mental health system issues and challenges in LAMICs are now well knownCitation6 (see text box). Mental health is still a low priority in most LAMICs and therefore attracts little government attentionCitation7 and weak investment.Citation8,9 There are low levels of mental health literacy in populations and also low population demand for services. There is therefore both little investment in developing mental health services and a shortage of everything necessary—skilled workers, health facilities, and drugs.Citation9–11 The available mental health workforce is poorly distributed and, in many places, almost entirely limited to large urban centers and mental hospitals.Citation12–14 The great majority of the population has little or no access to mental health assessment, treatment, and care.Citation15,16 In culturally diverse populations, services are typically provided only in the dominant language and culture. Neglect and abuse of people with mental illness are frequently found in mental hospitals, in social institutions for the mentally ill homeless and destitute,Citation17 and in the community.Citation18 Stigma, discrimination, and human rights abuses are ubiquitousCitation19 and will require concerted efforts to eliminate.Citation19–21 The frequently extreme poverty of the mentally ill results from the lack of free and accessible mental health services, coupled with social and economic exclusion.Citation4

MOMENTUM FOR CHANGE

While effective mental health services are unavailable for most people in LAMICs, there is a renewed commitment to focus attention on the mental health of populationsCitation5 and on the scaling up of mental health services that have the capacity to respond to mental health service needs.Citation22,23

In August 2007, the International Journal for Mental Health Systems (see below) was launched with the intention of focusing attention on mental health system development.Citation5 In September 2007, the Lancet published a series of papers that set out the current mental health situation in LAMICs and that proposed strategies for scaling up mental health services.Citation7,9,10,15,22,24 The Lancet's editor suggested that there was a need to launch a new movement for global mental health.Citation25 In 2008, following publication of a review of developments one year after the Lancet series,Citation26 the Movement for Global Mental Health was formally launched,Citation6 with the aim of “improv[ing] services for people with mental disorders worldwide through the coordinated action of a global network of individuals and institutions.”Citation27 In October 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) Mental Health Gap Action ProgrammeCitation31 (mhGAP) was launched. The intent of mhGAP is to scale up care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, with strategies identified particularly for resource-constrained settings and countries. In October 2011, the Lancet published a second seriesCitation4,11,19,Citation28–30 and reaffirmed its commitment to global mental health.Citation23

Mental health system development is making its way onto the agendas of bilateral development agencies and international development NGOs. The Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) Development for AllCitation32 disability strategy is a substantial achievement in promoting disability-inclusive development practice across AusAID programs. The strategy may open the way for increased attention to mental disorders, the single most important contributor to disability in LAMICs. In his statement of support for the WHO publication Mental Health and Development, the former Australian minister for international development noted that

Australia is committed to reducing poverty and achieving sustainable development in developing countries, and improving responses to people with mental illness is an important building block towards achieving this … Unless the needs of people with disability, including those with mental illness, are met, it will not be possible to achieve the targets of the Millennium Development Goals by 2015.Citation33

In 2009, the Australian minister for development assistance launched the International Observatory on Mental Health Systems, an initiative of the Centre for International Mental Health.Citation34,35 The UK Department for International Development has supported two rounds of major funding for Research Program Consortia to “improve[e] mental health services in low income countries.”Citation36 Atlantic Philanthropies, a U.S.-based philanthropic organization, has supported two major mental health system development projects in Vietnam, one of which is the National Taskforce for Mental Health System Development in Vietnam.Citation37

Mental health has been included among the priority areas for research by the newly established Global Alliance for Chronic Disease,Citation9 an initiative that brings together six of the world's foremost health agencies, which collectively manage an estimated 80% of all public health research funding. Linked with this initiative is the Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health project,Citation38 led by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, Wellcome Trust, McLaughlin-Rotman Centre for Global Health, and London School of Tropical Medicine. In July 2011, Nature published the results of a project setting priorities for global mental health research.Citation39 The National Institute of Mental Health has funded three collaborative hubs for international research on mental health and has issued a call for further proposals,Citation40 and Grand Challenges Canada has made available a sum of $20 million for Integrated Innovations for Global Mental Health.Citation38

There is general agreement that scaling-up activities must be evidence based and that the effectiveness of such activities must be evaluated. If these requirements are to be realized, it will be essential to strengthen capacity in countries to conduct rigorous monitoring and evaluation of system-development projects and to demonstrate sustained benefits to populations. Failure to sustain long-term gains from even well-designed and -implemented community mental health system development projects is a source of serious concern and is all too common.

CIMH MENTAL HEALTH SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM

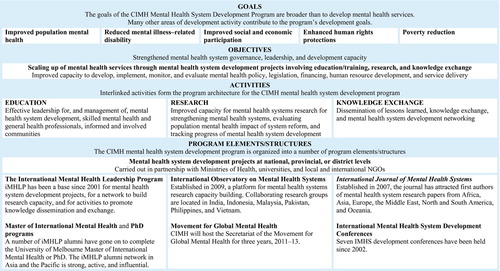

The Centre for International Mental Health (CIMH) has been involved in mental health system development work since the centre was established in 1996. This early work demonstrated with great clarity that the key issue was leadership, and supported a developing view that effective mental health system development is not possible without sustained and distributed leadership.Citation41,42 The CIMH development program () began to assume programmatic coherence in 2001 with the establishment of the International Mental Health Leadership Program (iMHLP), a collaboration between the CIMH, University of Melbourne, and Department of Social Medicine (now Department of Global Health and Social Medicine), Harvard Medical School (in particular, Professor Byron Good and Dr. Alex Cohen).

The goals of the CIMH program are to improve population mental health in LAMICs and in postconflict and postdisaster settings, reduce mental illness–related disability, improve social and economic participation by people with mental disorders, enhance human rights protections for people with mental disorders, and reduce poverty that is related to mental disorders.

EDUCATION AND TRAINING: iMHLP, MIMH, AND PHD PROGRAMS

The goals of iMHLP,Citation43 established in 2001, have remained unchanged: to contribute to the development of effective mental health systems by providing training and mentoring in leadership. The program is aimed at mental health professionals and managers of all disciplines who are in a position to contribute to the development of mental health systems that protect and enhance the human rights of people with mental illness and that are effective, appropriate, accessible, and affordable. The focus of the program is primarily on training leaders for work in developing countries.Citation44 iMHLP is a four-week intensive seminar that is followed by mentoring and by supervision of projects in participants’ home countries. In addition to formal teaching in leadership skills, the program provides an introduction to mental health policy development and implementation; mental health financing; service design with a focus on community mental health services; human resources for mental health; advocacy and human rights; and mental health systems research. Research- and service-development projects carried out by iMHLP participants are supervised by program faculty and by senior colleagues in the country in which the project is being carried out. During the program's decade of operation, a network of more than 170 alumni has been established across 18 countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Many of the alumni are now in influential positions in ministries of health, academic departments, WHO, professional associations, and other organizations.

Using iMHLP as a model, the first Master of International Mental Health (MIMH) program was established in 2003. Several iMHLP graduates have undertaken PhD-level studies in the CIMH. iMHLP, MIMH, and PhD alumni are often key collaborators on development and research projects on mental health systemsCitation16,18,Citation45–53 and in other CIMH development activities, such as the National Taskforces on Mental Health System Development in Indonesia and VietnamCitation26 and the International Observatory on Mental Health Systems.Citation34,35

BUILDING RESEARCH CAPACITY

Major advances in pharmacological and other treatments for mental disorders in recent decades have produced few benefits to most of the world's populations because the mental health systems that are required to deliver such treatments are poorly developed. Whereas high-quality mental health treatment services can be found in the large urban centers in LAMICs, provincial, rural, and remote regions often have no mental health service capacity. In addition to limited service capacity, there is frequently also limited capacity to answer important questions about the mental health status and needs of populations, how mental health is most effectively maintained and illness prevented, whether populationwide health policy objectives have been developed and whether they are being achieved, and how health systems can effectively respond to the health needs of the population. High-quality, local research is required to provide the specific, culturally relevant information that is essential for mental health system planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. At present, however, efforts to scale up mental health servicesCitation22 in low-resource environments are hampered by lack of evidence concerning mental health systems, limited capacity to carry out research relevant to policies and practices, and limited capacity among policymakers and health system managers to make use of research findings in decision making. As the then director of the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse noted:

It is very important to have good, randomized, clinical trials providing evidence about the efficacy of new treatments but it is equally important to have research providing evidence that a mental health system in a given country, region or district is working better than another. In other words, what we urgently need to know is how to plan and organize services and improve the use of scarce financial and human resources in order to reach out to the mental health needs of the general population and to provide effective and humane services to those who need care.Citation54

The International Observatory on Mental Health Systems (IOMHS)Citation34,35,55 was inspired by, and modeled on, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies,Citation56 which “supports and promotes evidence-based health policy-making through comprehensive and rigorous analysis of the dynamics of health care systems in Europe.” The goals of IOMHS are (1) to foster the establishment of, and to support, a network for mental health systems research, education, and development that will produce evidence for mental health policy and practice in LAMICs and that will help build capacity for mental health system development, (2) to produce new knowledge to inform the development of mental health systems that are effective, accessible, equitable, culturally appropriate, affordable, and disability inclusive, and that protect the human rights of people with mental illness, and (3) to monitor and evaluate progress in the development of mental health systems in LAMICs.

IOMHS is a collaborative network of research groups, now focused on Asia and the Pacific, that will measure and track mental health system performance in participating countries at national and subnational (provincial and district) levels. The observatory will build the capability of partner organizations and networks to provide evidence-based advice to policymakers, service planners, and implementers, and will monitor the progress of mental health service scaling-up activities.

The design of the observatory's administrative structures and work programs is based on a strategic approach to strengthening mental health systems research capacity and reflects an effort to ensure that new knowledge is used for the benefit of people with mental illness. The IOMHS's approaches to strengthening research capacityCitation35 are outlined in the text box.

DISSEMINATION AND EXCHANGE OF KNOWLEDGE

International Journal of Mental Health Systems

The International Journal of Mental Health Systems commenced publication in August 2007. It is an open-access, peer-reviewed journal that is part of the stable of Biomed Central independent journals. It has an international editorial board with members from 27 countries—in Africa, North and South America, East and South Asia, Europe, and Oceania—and from many disciplines. The journal is intended as the place to which

mental health system researchers, Health Ministers’ advisers, policy makers, mental health consultants advising countries on mental health system development, teachers in psychiatry, nursing, psychology, social work and public health courses, clinicians involved in mental health system reform, and others will turn for the latest research and policy information on how to build equitable, accessible, efficient, high quality mental health systems.Citation5

The number of scientific journals and consequently scientific papers devoted to treatment is more abundant than the literature devoted to documenting, analysing and assessing mental health services and mental health system development. The plethora of information on treatment and the prevailing clinical perspective should be gently replaced or, at least, balanced by an effort to bring a public health perspective in mental health. In this sense, it is important to have a journal focusing on mental health system development, which has the capacity of networking good practice in service organization, giving voice to successful experiences including those from low and middle income countries, promoting health services research and mental health services assessment.Citation54

The journal has now published over 100 papers, with first authors from every continent. In the difficult, open-access publishing environment, where authors are required to pay substantial article-processing charges, the journal has survived and is growing.

The International Mental Health System Development Conferences

Seven International Mental Health System Development Conferences were held between 2002 and 2010 in Beijing, Hong Kong, Melbourne, and Taipei. The first and the third were focused on developing leadership and on building capacity in mental health systems research. Each of the other five focused on mental health system development in a specific region or country: Aceh, China, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Taiwan. The primary purpose of these conferences is to strengthen the mental health system development network in Asia and to facilitate collaboration. The seventh conference,Citation57 held in Melbourne in 2010, is briefly described below as part of the Sri Lanka case example.

BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER: SRI LANKA

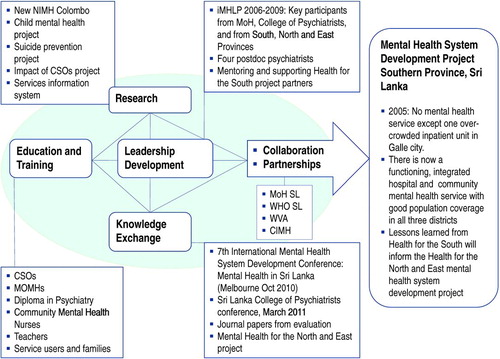

I will use Sri Lanka as a case study to highlight the ways in which the elements of the CIMH program () are integrated for the purpose of mental health system development. The details of the Sri Lanka project and its outcomes can be found in a recently completed evaluation report.Citation58 Here I will limit myself to illustrating how the elements of the CIMH program came into play during the course of this project ().

Figure 2. Structure of the CIMH mental health system development program and outcomes of the Health for the South project. CIMH, Centre for International Mental Health; CSO, community service officer; iMHLP, International Mental Health Leadership Program; MoH, Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition; MOMH, medical officers of mental health; NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health; SL, Sri Lanka; WHO, World Health Organization; WVA, World Vision Australia.

In the context of a long-running civil war resulting in massive suffering, death, and displacement over almost three decades, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami brought further devastation to the coastal areas of Sri Lanka and resulted directly in 35,000 deaths, many more injuries, and several hundred thousand people displaced from their homes. It fractured communities and destroyed infrastructure and livelihoods. Nearly one million people were affected in 13 districts, including the three districts of the Southern Province—Galle, Matara, and Hambantota. The disaster brought into sharp relief the importance of population mental health and the general absence of mental health services for those in Sri Lanka who needed them.

Many international NGOs, bilateral aid agencies, and UN agencies committed money and technical expertise to a program of reconstruction and recovery following the tsunami. During 2005 and 2006, WHO provided critical support to the Directorate of Mental Health Services of the Sri Lanka Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition in developing a national mental health policy and implementation plan. As part of this policy, the government of Sri Lanka committed itself to strengthening mental health services, developing a community focus for service delivery, and ensuring that services were accessible to all who needed them.

In 2006, World Vision Australia commissioned an investigationCitation59 of the feasibility of developing a model community mental health system in Southern Province, whose population of 2.3 million people was spread across three districts and a large geographical area. One 58-bed, acute psychiatric inpatient unit was available at the Karapitiya General Teaching Hospital in Galle, and two intermediate units were available in Ridiyagama (45 beds) and Unawatuna (40 beds) that housed people with chronic mental disorders for long periods. Virtually no community mental health services were available, and most people with mental illness received no treatment. The investigation's recommendations were incorporated into the design of the Health for the South Community Mental Health Project (H4S Project).

With funding of $1.1 million over three years, the H4S Project commenced in May 2007 and ended in December 2010. The project goal was to assist the Directorate of Mental Health Services in implementing a pilot project in the Southern Province of Sri Lanka to support the vision of the National Mental Health Policy for Sri Lanka, which was to develop a planned, comprehensive, community-based mental health service organized and implemented through coordination at the national, provincial, district, and community levels, and integrated with general health services at every level of care.

The key partners in the H4S Project were the Directorate of Mental Health of the Ministry of Health, the Provincial and District Directors of Health Services, the WHO Country Office, World Vision Australia, and CIMH. The project was funded by World Vision Australia, authorized and supported by the government of Sri Lanka, and managed by WHO, with CIMH providing technical advice and assistance.

Key senior Sri Lankan health professionals participated in the International Mental Health Leadership Program. They included the national director of mental health services, the provincial director of health services of Southern Province, the Hambantota District director of health services, the president of the Sri Lanka College of Psychiatrists, and two psychiatrists newly appointed to Hambantota and Matara Districts. Four medical doctors have undertaken a yearlong postdoctoral program in CIMH.

Substantial progress has been made in developing the mental health workforce:Citation58 establishing a new Diploma in Psychiatry, a one-year training program to address the extreme shortage of psychiatrists in Sri Lanka; training of Medical Officers of Mental Health, who provide the bulk of the primary care–based psychiatric assessment and treatment; training for community mental health nurses; and training and support for community-level mental health volunteers, the Community Service Officers. Training programs have been developed and delivered for large numbers of primary school teachers. Attention has also turned to improving the general community's level of knowledge about mental health and illness, and, through the creation of consumer and family associations, to encouraging people with mental illness and their families to engage in advocacy for mental health.

Several research projects relevant to policy and practice have been completed, including a WHO Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems project,Citation60 others focusing on child mental healthCitation61 and attempted suicide by pesticide poisoning,Citation62 and an evaluation of the impact of the Community Service Officers. With support from WHO, the H4S Project, and other donors and partners, the main mental hospital in Colombo has been radically improved and has been designated the Sri Lanka National Institute of Mental Health.

The objective of developing and implementing a model of community mental health services, in line with the National Mental Health Policy of Sri Lanka, has largely been achieved. A comprehensive, community-focused model of mental health services has been established in all three districts of Southern Province. This effort has included the following: acute inpatient units in the district general hospitals of Hambantota and Matara (in addition to the one in Galle); intermediate-care facilities at Unawatuna and Ridyagama (which previously housed long-stay patients with chronic illness but are being transformed into residential rehabilitation facilities); community outreach clinics in most divisions in each district to treat patients in the community; a national toll-free telephone service for mental health advice and counseling; a basic mental health information system in each district; and functioning procedures for intersectoral coordination, including health, social affairs, justice, education, and the police.

The challenges of working in the poorest district in the country and in the context of a continuing civil war were substantial. A number of lessons were learned in the process. The most important were that leadership matters most and that effective mental health system development is possible even in unusually difficult environments.Citation58 A year after the completion of the project, the system developments that were accomplished are being sustained and extended by government support.

As a result of active and joint advocacy by World Vision Australia and CIMH, AusAID funded a project focused on developing the mental health system in Sri Lanka's Northern Province. World Vision will “assist the Ministry of Health in the implementation of the community based components of the National Mental Health Policy in the Northern Province through the ‘Reconciliation through integration of Mental Health in Northern Districts’ (REMIND) in Sri Lanka,” a project that will be carried out in collaboration with the Sri Lankan College of Psychiatrists.Citation63

The 2010 International Mental Health System Development ConferenceCitation64 focused on mental health development needs in the Northern and Eastern Provinces, which had been devastated by the final phase of the civil war. Among the invited participants were the deputy secretary of the Department of Health, the acting head of the national Directorate of Mental Health, the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, the former mental health adviser in the WHO Country Office, and the head of the AusAID Sri Lanka program. The purpose of the meeting was to review the mental health situation in the Northern and Eastern Provinces and to develop a consensus about how to develop community mental health services. Following the conference, CIMH, the Ministry of Health, and the directors of health services of the Northern and Eastern Provinces made a successful submission to AusAID for the Leadership for Mental Health for the North and East of Sri Lanka project. This project will enable key mental health professionals from Northern and Eastern Provinces to participate in the International Mental Health Leadership Program and to carry out mental health system research and development projects with supervision and mentoring by iMHLP faculty and the Sri Lankan members of the H4S Project.

World Vision Australia's REMIND project and the CIMH project described immediately above are complementary in their objectives, with the first focusing on infrastructure for mental health services and the second focusing on skills and capabilities of key people. Both will be informed by the lessons learned from the H4S Project and will contribute to the development of mental health services both nationally and in the north and east.

CONCLUSION

I have attempted in this article to give an overview of the CIMH approach to mental health system development. The program architecture no doubt betrays the fact that it has been developed in the context of persistently inadequate resources, shifting and unpredictable opportunities, and grants from various agencies, each with its own objectives and expectations—and few with the flexibility and duration required for system development.

The consistent thread that runs through CIMH's work is the conviction that leadership matters most. Without skilled, sustained leadership at multiple levels—most importantly, from national and local governments—efforts to develop or strengthen mental health systems will fail. And yet, even in what would appear to be the most unpromising of settings, mental health system development has been shown to be possible, even with very modest investment.

In order for such development to succeed, it is necessary to build partnerships that can be sustained over the long haul. The quality of the relationships will be much more important than the specific details of project design. These relationships, like any others, need to be based on such things as honesty, mutual respect, and trust, supplemented by a joint commitment to equity and to protecting the rights of people with mental illness. It is also helpful and even important to enjoy each other's company—which makes it easier to continue working collaboratively when things might not be going so well.

Despite the significant gains that have been made in recent years in putting mental health system development on the general development agenda, there is still a very long way to go. Governments, bilateral and other development agencies, and the large philanthropic organizations are starting to appreciate the importance of population mental health. When the necessary funds begin to flow at a scale that is needed, we need to be ready and to be able to scale up our system-development efforts rapidly and with confidence. The approach that has been presented here has all of the necessary elements and is rapidly scalable.

Declaration of interest: The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007;6:168–76.

- Levi F, La Vecchia C, Saraceno B. Global suicide rates. Eur J Public Health 2003;13:97–8.

- Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Measuring the burden of neglected tropical diseases: the global burden of disease framework. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2007;1:e114.

- Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S, Poverty and mental disorders: breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011;378:1502–14.

- Minas IH, Cohen A. Why focus on mental health systems? Int J Ment Health Syst 2007;1:1.

- A movement for global mental health is launched [Editorial]. Lancet 2008;372:1274.

- Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2007;370:1164–74.

- Saxena S, Sharan P, Saraceno B. Budget and financing of mental health services: baseline information on 89 countries from WHO's project atlas. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2003;6:135–43.

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007;370:878–89.

- Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I, Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet 2007;370:1061–77.

- Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet 2011;378:1654–63.

- World Health Organization. Mental health atlas. Geneva: WHO, 2005.

- Saraceno B, Saxena S. Mental health resources in the world: results from Project Atlas of the WHO. World Psychiatry 2002;1:40–4.

- World Health Organization. Mental health atlas 2011. Geneva: WHO, 2011.

- Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, No health without mental health. Lancet 2007;370:859–77.

- Maramis A, Van Tuan N, Minas H. Mental health in southeast Asia. Lancet 2011;377:700–2.

- Minas H. Mentally ill patients dying in social shelters in Indonesia. Lancet 2009;374:592–3.

- Minas H, Diatri H. Pasung. Physical restraint and confinement of the mentally ill in the community. Int J Ment Health Syst 2008;2:8.

- Drew N, Funk M, Tang S, Human rights violations of people with mental and psychosocial disabilities: an unresolved global crisis. Lancet 2011;378:1664–75.

- Irmansyah I, Prasetyo YA, Minas H. Human rights of persons with mental illness in Indonesia: more than legislation is needed. Int J Ment Health Syst 2009;3:14.

- Puteh I, Marthoenis M, Minas H. Aceh Free Pasung: releasing the mentally ill from physical restraint. Int J Ment Health Syst 2011;5:10.

- Chisholm D, Flisher AJ, Lund C, et al.; Lancet Global Mental Health Group. Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. Lancet 2007;370:1241–52.

- Patel V, Boyce N, Collins PY, Saxena S, Horton R. A renewed agenda for global mental health. Lancet 2011;378:1441–2.

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2007;370:991–1005.

- Horton R. Launching a new movement for mental health. Lancet 2007;370:806.

- Patel V, Garrison P, Mari J, Minas H, Prince M, Saxena S. The Lancet's series on global mental health: 1 year on. Lancet 2008;372:1354–7.

- Movement for global mental health. http://www.globalmentalhealth.org/articles.html

- Eaton J, McCay L, Semrau M, Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011;378:1592–603.

- Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet 2011;378:1515–25.

- Tol WA, Barbui C, Galappatti A, Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings: linking practice and research. Lancet 2011;378:1581–91.

- World Health Organization. mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Programme: scaling up care mental, neurological, and substance use disorders. Geneva: WHO, 2008.

- Australian Agency for International Development. Development for all: towards a disability-inclusive Australian aid program 2009–2014. Canberra: AusAID, 2008.

- Funk M, Drew N, Freeman M, Faydi E. Mental health and development: targeting people with mental health conditions as a vulnerable group. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010.

- Minas H. International observatory on mental health systems: a mental health research and development network. Int J Ment Health Syst 2009;3:2.

- Minas H. International observatory on mental health systems: structure and operation. Int J Ment Health Syst 2009; 3:8.

- R4D: research for development. At http://www.dfid.gov.uk/r4d/

- International Mental Health. Taskforce on community mental health system development in Vietnam. 2010. http://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/internationalmentalhealth/2010/03/08/national-taskforce-on-community-mental-health-system-development-in-vietnam/

- Grand Challenges Canada. Integrated innovations for global mental health. 2011. http://www.grandchallenges.ca/grand-challenges/gc4-non-communicable-diseases/mentalhealth/

- Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature 2011;475:27–30.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Collaborative Hubs for International Research on Mental Health (U19). 2011. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-MH-12-110.html

- Minas H. Leadership for change in complex systems. Australas Psychiatry 2005;13:33–9.

- Callaly T, Minas H. Reflections on clinician leadership and management in mental health. Australas Psychiatry 2005;13:27–32.

- International Mental Health Leadership Program. http://www.cimh.unimelb.edu.au/learning_and_teaching/pdp/imhlp

- Beinecke R, Minas H, Goldsack S, Peters J. Global mental health leadership training programmes. Int J Leadersh Public Serv 2010;6:63–72.

- Tan SM, Azmi MT, Reddy JP, Does clinical exposure to patients in medical school affect trainee doctors’ attitudes towards mental disorders and patients? A pilot study. Med J Malaysia 2005;60:328–37.

- Reddy JP, Tan SM, Azmi MT, The effect of a clinical posting in psychiatry on the attitudes of medical students towards psychiatry and mental illness in a Malaysian medical school. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2005;34:505–10.

- Irmansyah I, Prasetyo YA, Minas H. Human rights of persons with mental illness in Indonesia: more than legislation is needed. Int J Ment Health Syst 2009;3:14.

- Lin CY, Huang AL, Minas H, Cohen A. Mental hospital reform in Asia: the case of Yuli Veterans Hospital, Taiwan. Int J Ment Health Syst 2009;3:1.

- Colucci E, Kelly CM, Minas H, Jorm AF, Nadera D. Mental health first aid guidelines for helping a suicidal person: a Delphi consensus study in the Philippines. Int J Ment Health Syst 2010;4:32.

- Irmansyah I, Dharmono S, Maramis A, Minas H. Determinants of psychological morbidity in survivors of the earthquake and tsunami in Aceh and Nias. Int J Ment Health Syst 2010;4:8.

- Minas H, Zamzam R, Midin M, Cohen A. Attitudes of Malaysian general hospital staff towards patients with mental illness and diabetes. BMC Public Health 2011;11:317.

- Colucci E, Kelly C, Minas H, Jorm A, Suzuki Y. Mental health first aid guidelines for helping a suicidal person: a Delphi consensus study in Japan. Int J Ment Health Syst 2011;5:12.

- Colucci E, Kelly CM, Minas H, Jorm AF, Chatterjee S. Mental health first aid guidelines for helping a suicidal person: a Delphi consensus study in India. Int J Ment Health Syst 2010;4:4.

- Saraceno B. Mental health systems research is urgently needed. Int J Ment Health Syst 2007;1:2.

- Minas H. IOMHS: strengthening mental health systems research capacity. Rom J Psychiatry 2009;XI:124–8.

- European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. http://www.euro.who.int/en/who-we-are/partners/observatory

- Mental health strategies in post-crisis Sri Lanka. 2010. http://upclose.unimelb.edu.au/episode/episode-120-mental-health-strategies-post-crisis-sri-lanka

- Minas H, Mahoney J, Kakuma R. Health for the South community mental health project, Sri Lanka: evaluation report. Melbourne: World Vision Australia, 2011.

- Minas H. Health for the South: community mental health project [Report]. Melbourne: World Vision Australia, 2006.

- World Health Organization. Hambantota WHO-AIMS report. Colombo: WHO Sri Lanka, 2007.

- Jayasinghe A. Child mental health problems in Hambantota District, Sri Lanka [Research report]. Colombo: World Health Organization, 2010.

- Pearson M, Weerasinghe M, Pieris R. Pesticide regulation and public health in farming communities: an examination of the impact of pesticide restriction on farmers’ decision making. Colombo: South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, 2010.

- World Vision implements mental health initiative in the north. 2011. http://srilanka.wvasiapacific.org/whats-new/latest/202-world-vision-implements-mental-health-initiative-in-the- north

- 7th Mental Health System Development Conference. Mental health in Sri Lanka. Centre for International Mental Health, 2010. http://www.cimh.unimelb.edu.au/news_events/mediacentre/cimh_major_conferences_and_events