Abstract

Objectives: To describe histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features of synovial biopsies of amyloid arthropathy associated with multiple myeloma (MM).

Methods: Synovial biopsies from affected joints of two patients with MM and amyloid arthropathy were examined with light and electron microscopy, and immunohistochemically for expression of CD3, CD8, CD20, CD38, CD68, Ki-67 and vWF. Results were compared to values from osteoarthritis (OA, n = 26), rheumatoid arthritis (RA, n = 24) and normal (n = 15) synovial membranes.

Results: There was no or only mild lining hyperplasia. Vascular density was not elevated, and there were few Ki-67+ proliferating cells in the stroma. The Krenn synovitis score classified one specimen as “low-grade” and one as “high-grade” synovitis. CD68+ and CD3+ cells were the predominant mononuclear inflammatory cells, whereas CD20+ and CD38+ cells were absent from both synovial membrane and synovial fluid sediment. Electron microscopy demonstrated amyloid phagocytosis by synovial macrophages. In hierarchical clustering the two amyloid arthropathy specimens were more closely related to OA than to RA or normal synovium.

Conclusions: This first detailed immunohistological analysis of MM-associated amyloid arthropathy suggests that it is a chronic synovitis that evolves despite the loss of humoral immunity seen in advanced MM. Instead, amyloid phagocytosis by synovial macrophages likely triggers and perpetuates local disease.

Introduction

Monoclonal gammopathies such as multiple myeloma (MM) or Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia can lead to the deposition of immunoglobulin light chains in various organs including heart, kidneys and joints. Light chain aggregation in the characteristic beta pleated sheets results in the formation of amyloid, termed AL amyloid [Citation1], leading to dysfunction of the affected organ. Formation of amyloid in the synovial membrane may lead to an uncommon form of arthritis, which is generally referred to as amyloid arthropathy. Numerous cases of MM-associated amyloid arthropathy (MAA) have been reported in the literature (e.g. [Citation2]). We have recently completed a systematic analysis of 101 cases of MAA and described the spectrum of its clinical presentations [Citation3]. Among other findings, this analysis revealed that MAA is more diverse than originally thought, that it is often clinically mistaken for RA and that there are no effective treatments. Importantly, its histopathologic features have not been described in sufficient detail, although they might give clues to its pathogenesis and reveal features that may serve to distinguish it from RA. Notably, there are no data on immunohistological phenotyping of the inflammatory cells in affected synovial membranes, likely due to the rare availability of tissue from biopsy or autopsy. Using synovial biopsies from two new cases of MAA, we here present the first immunohistochemical analysis of this uncommon entity. Both specimens feature a synovitis with inflammatory infiltrates consisting predominantly of macrophages and T cells but lacking B or plasma cells. We provide evidence that, in the absence of humoral immunity, amyloid phagocytosis by synovial professional phagocytes is a key element of the pathogenesis of MAA.

Patients and methods

Patients and synovial biopsies

Both patients were treated at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center and had closed needle biopsies of the synovial membrane [Citation4] performed for diagnostic purposes. Demographic and laboratory data are summarized in Table 1.

Patient 1 was a 58-year-old male with MM complicated by transfusion-dependent anemia, lytic bone lesions, and myeloma kidney requiring dialysis. He presented with left shoulder pain and swelling two months after diagnosis of MM, followed by bilateral hand and shoulder swelling with morning stiffness lasting hours. Examination demonstrated left second metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint swelling, right flexor tenosynovitis, bilateral shoulder effusions, flexion contractures of both elbows, and decreased range of motion in the cervical spine. Joint aspiration revealed a synovial fluid cell count of 2500 cells/mm3 (6% PMN, 17% lymphocytes, 77% synovial lining cells). Repeat aspiration one week later revealed a cell count of 1050 cells/mm3 and amyloid in the synovial fluid sediment by Congo Red staining. There were no crystals in either aspirate. A synovial biopsy of the right shoulder joint was performed after another week. MM therapy, which had been initiated prior to the biopsy, included one cycle of melphalan (12 mg/d × 4 days), prednisone (60 mg/d × 4 days), and apheresis to treat renal failure suspected to have resulted from free Ig light chains. Joint symptoms improved with this treatment, but therapy was eventually halted due to nausea. The patient died four months after the biopsy.

Patient 2 was a 77-year-old male with a history of coronary artery disease, non-insulin dependent diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal insufficiency and MM. Complications of MM included anemia, painful lytic bone lesions, a paraspinal extramedullary plasmacytoma, and worsening kidney disease requiring dialysis. Three months after the diagnosis, the patient presented with right shoulder, right knee and bilateral MCP pain. Examination showed swollen and tender knees in addition to warmth, erythema and tenderness in MCP joints bilaterally. A synovial biopsy of the right knee was performed. Cytologic examination of synovial fluid was reported as “few mononuclear cells”, but absolute or differential synovial fluid leukocyte counts were not enumerated. There were no crystals. Amyloid was demonstrated in synovial fluid sediment by Congo red staining. Treatment prior to the biopsy included two cycles of melphalan (8 mg/m2/day × 4 days) and prednisone (100 mg/day × 4 days) followed by palliative radiation therapy for bone lesions. The patient was taking prednisone 10 mg daily at the time of the biopsy. He passed away 3 months after the biopsy.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Specimens were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (thickness, 5 µm) and either stained with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) or immunostained for CD3 (T cells), CD8 (cytotoxic T cells), CD20 (B cells), CD38 (plasma cells), CD68 (macrophages), Ki-67 (proliferating cells) and von Willebrand Factor (vWF, vascular endothelium), using a semi-robotic immunostainer (Ventana Benchmark, Ventana, Tucson, AZ) and commercially available antibodies. Positive staining cells or vessels were counted under 400× magnification as described previously [Citation5–8] and expressed as the number of positive staining cells per mm2. A minimum of three embedded tissue pieces and ten 400× microscopic fields were evaluated per specimen. Previously published results from 24 RA, 26 OA and 15 normal synovial membranes [Citation5–8] were used as reference values. Anti-kappa and anti-lambda immunoglobulin light chain immunostains were performed in a commercial reference laboratory. The histological severity of synovitis was quantified with the 3-component synovitis score according to Krenn et al. [Citation9,Citation10]. Tissue from patient 1 was also fixed in paraformaldehyde-glutaraldehyde, processed for electron microscopy (EM) according to standard practice and analyzed with a Zeiss EM-10 transmission electron microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY) [Citation11].

Cluster analysis

Average cell or vessel counts per high power field were square root transformed and standardized to mean zero and standard deviation one before analysis. The “complete linkage” method provided by the method “hclust” of the R package “stats” [Citation12] was used for hierarchical clustering.

Results

Histological findings

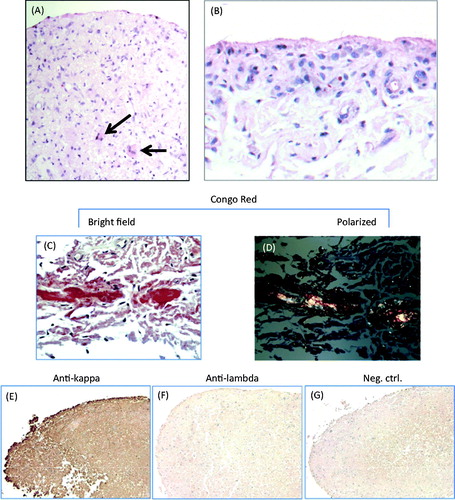

Lining thickness was generally 1–2 cell layers in both specimens, and very rarely exceeded three layers, suggesting that there was no significant lining hyperplasia. (A) shows the typical appearance of the specimen from Pt. 1, with normal lining thickness and mildly increased stromal cellularity. (B) shows focal lining hyperplasia with juxta-intimal pericapillaritis, both seen occasionally in the specimen from Pt. 2. There were mild–moderate lymphocytic infiltrates and diffuse stromal infiltration with macrophages in specimens from both the patients, but plasma cells were not seen. Stromal cellularity (other than macrophages) was normal or only mildly increased. The 3-component synovitis score classified Pt. 1 as low-grade synovitis (lining hyperplasia: 0; stromal cellularity: 2; inflammatory infiltrates: 1; total score, 3) and Pt. 2 as high-grade synovitis (lining hyperplasia: 1; stromal cellularity: 3; inflammatory infiltrates: 1–2; total score, 5–6). Subintimal extracellular amyloid deposits were seen easily in specimens from both patients: in H&E stained sections as diffuse reddish appearing lesions, and in Congo Red stained sections as the typical focal carmine red reaction (bright field) and the apple-green pattern (polarized light) (C and D). There were no focal amyloid deposits in the vessel walls. Immunohistochemical staining revealed diffuse deposition of Ig kappa light chains in both patients, which covered much larger areas than the amyloid deposits apparent by Congo Red stain (E–G, shown for Pt. 1 only).

Figure 1. Selected histological findings: (A) and (B) hematoxylin-eosin stains. (A) photomicrograph showing normal lining thickness with increased stromal cellularity in part due to infiltrating large mononuclear cells. The arrow points to large macrophages within focal amyloid deposits (patient 1). (B) Example of mild focal lining hyperplasia and juxta-intimal pericapillaritis occasionally seen in the specimen from patient 2. (C) and (D) Detection of amyloid by Congo Red stain (patient 1). (C) Typical carmine red deposits as seen in bright field view. (D) Typical birefringence seen under polarizing light. (E–G) Immunohistochemical detection of kappa light chain (patient 1). There is diffuse deposition of kappa (E), but not of lambda (F) light chains, consistent with AL amyloidosis. G, negative control.

Quantitative immunohistochemical findings

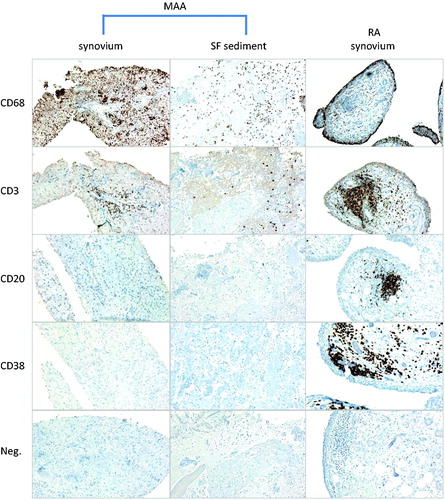

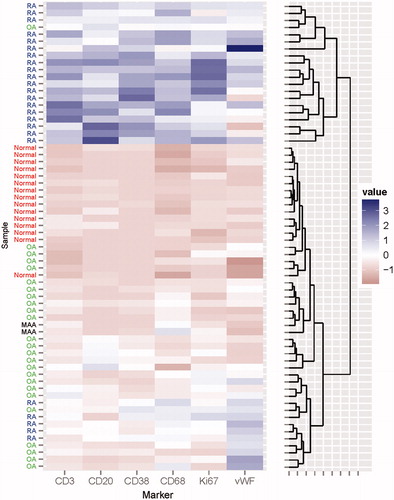

Images of selected immunohistochemical findings in synovial tissue and synovial fluid sediment from patient 1 and (for purpose of comparison) in synovial tissue from a patient with RA are shown in . Immuno-histomorphometric results are summarized in and are also compared to previously published values for normal synovium, OA synovium and RA synovium [Citation5–8]. In the surface layer of the lining, total numbers and relative proportions of CD68+ cells were elevated compared with normal synovium, suggesting some recruitment of CD68+ macrophages into the lining. There were diffuse CD68+ infiltration and scattered CD3+ lymphocytic infiltrates in the subintima, both at densities between the mean values for OA and RA. Of note, there were essentially no CD20+ or CD38+ cells in either specimen. The absence of CD20+ and CD38+ cells was confirmed when paraffin-embedded sections of synovial fluid sediment were stained for the same antigens (, middle panel). Quantitatively, Ki-67+ cell densities were slightly elevated compared to normal synovium, i.e. to a similar extent as in OA. Consistent with this relatively low degree of cellular proliferation, vascular density was nearly identical to the mean values measured in normal synovium, suggesting that there was no abnormal vascular proliferation (neovascularization). Using hierarchical clustering, the results of these quantitative immunohistochemical measurements were then used to cluster the MAA specimens with respect to the 65 normal, OA and RA specimens (). In this analysis, the MAA specimens clustered together within a large clade of OA specimens, and they were most closely related to the OA subset containing low synovial loads of CD20+ and CD38+ cells.

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical findings. Immunohistochemical stains for CD68, CD3, CD20 and CD38. Chromogen, DAB (brown). Original magnification, 100×. Left panel: synovial biopsy from patient 1. Middle panel: paraffin-embedded synovial fluid sediment from patient 1. Right panel: synovial biopsy from a patient with RA with active disease despite treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Figure 3. Cluster analysis of the 2 MAA specimens with respect to RA, OA and normal synovium. Expression values in the synovial subintima (number of positive staining cells per mm2) of CD68, CD3, CD20, CD38, Ki-67 and vWF for MAA (n = 2), RA (n = 24), OA (n = 26) and normal synovium (n = 15) were used to construct a hierarchical tree of clusters for all specimens. The MAA specimens fall within a cluster of OA specimens and are clearly separated from the RA specimens.

Table 1. Demographic and laboratory data.

Table 2. Summary of histomorphometric results.

Amyloid phagocytosis

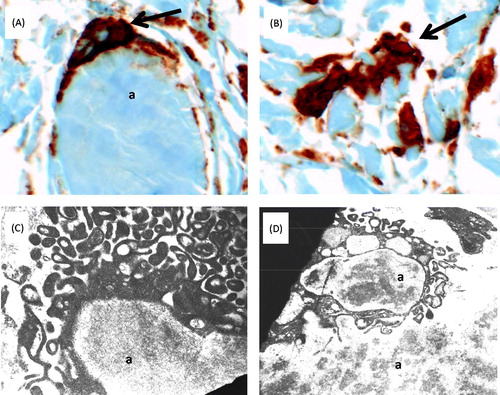

CD68 immunostaining identified many CD68+ macrophages abutting and/or engulfing the amyloid deposits in both patients. Examples from Pt. 1 are shown in (A) and (B). EM demonstrated cells with prominent cell processes abutting and/or engulfing extracellular amyloid deposits (C). Intracellular amyloid was seen inside phagosomes of macrophage-like cells, consistent with amyloid phagocytosis by these cells (D).

Figure 4. Amyloid phagocytosis in synovial tissue from patient 1. (A) and (B) Immunohistochemial detection of CD68+ macrophages (brown) engulfing (A) and interdigitating with (B) amorphous amyloid deposits (original magnification 400×). (C) and (D) Ultrastructural findings. (C) Phagocyte reacting to and surrounding a mass of amyloid (a); magnification approximately 12 000×. (D) Cell with completed amyloid phagocytosis; magnification approximately 7000×. Images were acquired with a Zeiss EM-10 transmission electron microscope, using thin sections from epoxy-embedded tissue. Tissue was obtained during the same biopsies as in . Abbreviation: a, amyloid.

Discussion

This first analysis of the immunohistological findings of MAA revealed specific features of these two specimens which – pending validation in additional specimens – might be used to differentiate it from other inflammatory arthropathies and give clues as to its pathogenesis: inflammatory infiltrates consisting predominantly of CD68+ macrophages, few T lymphocytes and essentially no cells of the humoral immune system, low stromal proliferation, only occasional intimal hyperplasia, and no neovascularization. How do these findings relate to previous findings in synovial biopsies of MAA? In our recent systematic analysis of MAA, synovial histology was described in some detail in only 15 cases [Citation3]. The prevailing picture was one of a relatively bland synovitis with mild-to-moderate mononuclear infiltrates, but immunophenotypic data on the infiltrates were not reported. The present two cases fully support these general histopathologic findings, but also identify the majority of the mononuclear inflammatory cells as CD68+ macrophages. As the arthropathy likely develops in the context of end-organ deposition of AL amyloid, MAA is expected to be a feature of advanced MM. A progressive humoral immunodeficiency is a common feature of advanced MM, as myeloma cells infiltrate the bone marrow [Citation13]. Thus, the absence of B and plasma cells from the inflammatory infiltrates in the two presented cases is consistent with the natural history of this disease, as well as potential effects of MM-directed chemotherapy.

Pathogenesis of synovitis in MM-associated amyloid arthropathy

The clustering analysis confirmed that MAA is immunohistologically distinct from RA, an autoimmune disease with prominent involvement of the B cell compartment. Importantly, the evolution of the arthropathy in these two MAA patients demonstrates that a symmetric polyarthritis can arise in individuals without a functioning B cell compartment. Indeed, there is some precedent to this in that a polyarthritis occurs in patients with congenital agammaglobulinemia [Citation14,Citation15], presumably because innate and cellular immunity suffice as long as adequate stimuli (such as frequent infections in this disorder) exist that can sustain chronic inflammation.

What might be the mechanism of the polyarthritis in the presented patients, and – perhaps – MAA in general? Both specimens featured widespread deposition of Ig light chains even in amyloid negative areas, and we cannot rule out that these non-fibrillar deposits at least contributed to the arthritis, e.g. by stimulating synovial fibroblasts and/or macrophages. However, we do not expect non-fibrillar light chain deposition per se to be responsible for the arthritis, as light chain deposition disease (LCDD, a complication of plasma cell dyscrasias) usually affects the kidney whereas only one case of LCDD-associated arthritis has been described [Citation16]. A more plausible explanation relates to phagocytosis of fibrillar amyloid by synovial macrophages. The immunostains identified the cells abutting the amyloid deposits as CD68+ macrophages, and EM clearly demonstrated amyloid phagocytosis by macrophage-like cells. Phagocytosis of amyloid can stimulate inflammasomes, leading to the proteolytic processing of pre-interleukin (IL)-1β to the mature IL-1β, which can be released into the extracellular environment and activate pro-inflammatory signaling cascades in other cells [Citation17]. Taken together, these findings allow us to speculate that MAA is mediated by innate immune mechanisms, specifically by activation of macrophage-associated inflammasomes, resulting in the chronic release of IL-1β and related cytokines in the synovial membrane. This would suggest that MAA is related to the arthritis resulting from certain autoinflammatory diseases such as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis or familial Mediterranean fever, which are also driven by IL-1β and respond well to IL-1β-directed treatments [Citation18,Citation19]. The pathogenetically most plausible disease-modifying treatment for MAA, then, would be inhibition of IL-1β with biologics such as anakinra or rilonacept. Indeed, anakinra has shown some efficacy in the treatment of smoldering MM [Citation20], but data on articular symptoms were not reported in that study. Interestingly, it was suggested that IL-1 inhibition acted by reducing IL-6 production by bone marrow stromal cells. IL-6 is known to be highly upregulated in activated macrophages in inflammatory arthropathies [Citation21]. Thus, IL-6 inhibition appears to be a plausible therapeutic strategy for MAA as well. Clearly, the potential roles of IL-1β and/or IL-6 in MAA and any resulting therapeutic implications require further study.

Limitations

This study is limited by the small number of patients studied. In addition, we cannot rule out that other forms of amyloidosis at least contributed to the arthropathy. Both patients received renal dialysis and were therefore at risk of dialysis-associated Aβ2M amyloidosis, which can lead to an arthropathy similar to MAA [Citation22]. Patient 2, due to the higher age, was also at risk of the senile form of transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR). Due to a lack of remaining synovial biopsy tissue we cannot rule out these possibilities with immunohistochemical stains. However, we consider both unlikely, partly due to the short duration of dialysis (2–3 months) and because ATTR typically features carpal tunnel syndrome or a painful compression neuropathy, but not the florid arthritis seen in these two patients [Citation22].

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

C. T. Mayer was supported by an American College of Rheumatology/Research and Education Foundation Health Professional Graduate Student Research Preceptorship award. WWK is supported by a Wellcome Trust studentship (09730/Z/11/Z). AME was supported by German-Egyptian Scientific Projects (GESP) grant no. 51309219 from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of the Arab Republic of Egypt. The study was supported in part by funds from the Helmholtz Association (Programs in Infection and Immunity and in Individualized Medicine, iMed). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Philadelphia VA Medical Center as part of a larger study of synovial histopathology. The need to obtain informed consent was waived due to the use of anonymized data.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ANA | = | antinuclear antibodies |

| ESR | = | erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| Ig | = | immunoglobulin |

| L | = | lymphocytes |

| LCDD | = | light chain deposition disease |

| M | = | monocytes |

| MM | = | multiple myeloma, MAA, multiple myeloma-associated amyloid arthropathy |

| ND | = | not determined |

| P | = | polymorphonuclear cells |

| RF | = | rheumatoid factor |

| SF | = | synovial fluid |

| SPEP | = | serum protein electrophoresis |

Acknowledgements

We thank Jan Dinnella and Katherine McKenna for administrative support, and Irene Loglisci, Roxann Thompson, Valice Matthews and John Romano (Philadelphia VA Medical Center, Department of Pathology) for help with histology, and Gilda Clayburne and Suzy Rothfus (Philadelphia VA Medical Center, Division of Rheumatology) for assistance with EM.

References

- Sipe JD, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Ikeda S, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Westermark P. Amyloid fibril protein nomenclature: 2012 recommendations from the Nomenclature Committee of the International Society of Amyloidosis. Amyloid 2012;19:167–70

- Gordon DA, Pruzanski W, Ogryzlo MA, Little HA. Amyloid arthritis simulating rheumatoid disease in five patients with multiple myeloma. Am J Med 1973;55:142–54

- Elsaman AM, Radwan AR, Akmatov MK, Della Beffa C, Walker A, Mayer CT, Dai L, et al. Amyloid arthropathy associated with multiple myeloma: a systematic analysis of 101 reported cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.07.004

- Schumacher HR. Synovial fluid analysis and synovial biopsy. In: Kelley WN, edr. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001:605–19

- Diaz-Torne C, Schumacher HR, Yu X, Gomez-Vaquero C, Dai L, Chen LX, Clayburne G, et al. Absence of histologic evidence of synovitis in patients with Gulf War veterans' illness with joint pain. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:1316–23

- Pessler F, Chen LX, Dai L, Gomez-Vaquero C, Diaz-Torne C, Paessler ME, Scanzello C, et al. A histomorphometric analysis of synovial biopsies from individuals with Gulf War Veterans' Illness and joint pain compared to normal and osteoarthritis synovium. Clin Rheumatol 2008;27:1127–34

- Ogdie A, Li J, Dai L, Paessler ME, Yu X, Diaz-Torne C, Akmatov M, et al. Identification of broadly discriminatory tissue biomarkers of synovitis with binary and multicategory receiver operating characteristic analysis. Biomarkers 2010;15:183–90

- Della Beffa C, Slansky E, Pommerenke C, Klawonn F, Li J, Dai L, Schumacher Jr HR, et al. The relative composition of the inflammatory infiltrate as an additional tool for synovial tissue classification. PLoS One 2013;8:e72494

- Krenn V, Morawietz L, Häupl T, Neidel J, Petersen I, König A. Grading of chronic synovitis – a histopathological grading system for molecular and diagnostic pathology. Pathol Res Pract 2002;198:317–25

- Slansky E, Li J, Haupl T, Morawietz L, Krenn V, Pessler F. Quantitative determination of the diagnostic accuracy of the synovitis score and its components. Histopathology 2010;57:436–43

- Schumacher HR, Jr. Multiple myeloma with synovial amyloid deposition. Rheumatol Phys Med 1972;11:349–53

- The R project for statistical computing. Available from: http://www.r-project.org/ [last accessed 18 Nov 2013]

- Pratt G, Goodyear O, Moss P. Immunodeficiency and immunotherapy in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 2007;138:563–79

- Lee AH, Levinson AI, Schumacher Jr HR. Hypogammaglobulinemia and rheumatic disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1993;22:252–64

- Robertson DM. Rheumatoid arthritis and agammaglobulinaemia. Can Med Assoc J 1960;82:81–4

- Rivest C, Turgeon PP, Senecal JL. Lambda light chain deposition disease presenting as an amyloid-like arthropathy. J Rheumatol 1993;20:880–4

- Masters SL, O'Neill LA. Disease-associated amyloid and misfolded protein aggregates activate the inflammasome. Trends Mol Med 2011;17:276–82

- Quartier P, Allantaz F, Cimaz R, Pillet P, Messiaen C, Bardin C, Bossuyt X, et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ANAJIS trial). Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:747–54

- Gillespie J, Mathews R, McDermott MF. Rilonacept in the management of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). J Inflamm Res 2010;3:1–8

- Lust JA, Lacy MQ, Zeldenrust SR, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, Kumar S, et al. Induction of a chronic disease state in patients with smoldering or indolent multiple myeloma by targeting interleukin 1{beta}-induced interleukin 6 production and the myeloma proliferative component. Mayo Clin Proc 2009;84:114–22

- Li J, Hsu HC, Mountz JD. Managing macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis by reform or removal. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012;14:445–54

- M'Bappe P, Grateau G. Osteo-articular manifestations of amyloidosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012;26:459–75