ABSTRACT

Background

Organisational culture in group homes for people with intellectual disabilities has been identified as an influence on service delivery and staff behaviour. The aim was to examine patterns of culture across group homes in disability organisations.

Method

The Group Home Culture Scale (GHCS) was used to measure staff perceptions of culture. Data were available from 260 staff who worked across 58 group homes managed by eight organisations. Using scatterplots and measures of dispersion, the scores on the seven GHCS subscales were examined for patterns of integrated (i.e., similarities) and differentiated (i.e., variability) culture within the organisations.

Results

Patterns of differentiated culture were found in six organisations for one or more GHCS subscales. Patterns of integrated culture were found in three organisations for one subscale. In two organisations, patterns of both integrated and differentiated culture were found.

Conclusions

The findings contribute to the conceptualisation of and research into organisational culture in group homes, with implications for changing and maintaining culture.

Implementation of deinstitutionalisation policies in developed countries (e.g., Australia, England, Sweden, and the United States) in the 1970s shifted the provision of supported accommodation services for people with intellectual disabilities from large segregated institutions to smaller community-based housing, such as group homes (Braddock et al., Citation2001). Group homes dispersed in the community and accommodating three to eight people became one of the main forms of supported accommodation services, which has continued to the present (Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2010). Much research has been conducted to identify the factors that contribute to delivering high quality group homes and people with intellectual disabilities experiencing good quality of life (QOL) outcomes (Bigby & Beadle-Brown, Citation2018).

Organisational culture has been identified by researchers as a factor that influences service delivery and staff behaviour in group homes (Felce et al., Citation2002). Culture has been variously defined and conceptualised in the organisational literature, although Hartnell et al. (Citation2011) identified common elements to include (a) being shared among its members; (b) consisting of collective beliefs, values, assumptions and norms; (c) existing at multiple levels (e.g., organisational and group levels); and (d) influencing staff members’ attitudes and behaviours.

In a review of propositions thought to influence QOL outcomes and the evidence for these, Bigby and Beadle-Brown (Citation2018) identified several about organisational culture. One proposition was that having a coherent culture across an organisation and within its services contributes to service quality. This proposition relates to a frequently discussed conceptualisation of organisational culture in the intellectual disability services literature (Clement & Bigby, Citation2010; Hastings et al., Citation1995; Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2012). In this conceptualisation, organisations have both formal and informal culture. Formal culture includes an organisation’s mission statement, policies and training (Felce et al., Citation2002). Informal culture includes staff members’ shared ways of working (Hastings et al., Citation1995). According to Emerson et al. (Citation1994), in services with incongruent formal and informal cultures, staff practices may be contrary to the organisation’s aims and expectations. This proposition of culture coherence in intellectual disability services has not been tested through research.

Studies into culture have involved services in which abuse of people with intellectual disabilities has been alleged (Cambridge, Citation1999; Marsland et al., Citation2007). The purpose of these studies has been to identify the characteristics of culture that may explain and prevent abuse. Cambridge (Citation1999), for example, completed a case study of a group home in which two people with intellectual disabilities were alleged to have been physically abused by multiple staff members. The findings suggested the presence of a “culture of abuse” (Cambridge, Citation1999, p. 294), characterised by isolation of the service and staff, ineffective staff supervision and management, intimidation of staff and managers by alleged perpetrators, institutionalised practices, staff inexperience, and anti-professionalism among staff. Similar findings were reported by Marsland et al. (Citation2007) in a qualitative study into indicators of abusive service cultures. In these studies of abuse and in a review of the literature (White et al., Citation2003), the researchers drew on the concept of the corruption of care, defined as the implementation of systems and practices that “constitute an active betrayal of the basic values on which the organisation is supposedly based” (Wardhaugh & Wilding, Citation1993, p. 5). Elements of this concept and findings from these studies arguably reflect incongruence between formal and informal culture, whereby staff members’ shared values and practices are contrary to the organisation’s values.

More recently, researchers have examined dimensions of culture associated with service quality and QOL outcomes for people with intellectual disabilities. In an ethnographic study of five underperforming group homes, Bigby et al. (Citation2012) identified five dimensions of culture proposed to have relevance to all group homes: (a) alignment of power-holders’ values with the organisation’s espoused values, (b) regard for residents, (c) perceived purpose, (d) working practices, and (e) orientation to change and new ideas. The descriptions of the culture in the underperforming group homes arguably resembled some of the characteristics of culture identified in the studies into abuse, suggesting that there are patterns across poor quality services. These similarities included some staff or a group of staff having a powerful influence on the ways things were done in the group homes, poor leadership, staff regarding the residents as different from themselves, staff practices contravening the organisations’ espoused values and aims, service isolation, and staff resisting ideas from people outside of the team (e.g., senior managers, professionals).

In contrast to examining culture in underperforming group homes, Bigby and Beadle-Brown (Citation2016) examined the culture in three better performing group homes. Using an ethnographic approach and Bigby et al.’s (Citation2012) five dimensions of culture as their framework, they found in these services that staff (a) held values that were aligned with the organisation’s espoused values, (b) held a positive regard for the residents, (c) perceived the purpose of their work as supporting each person to live the life they wanted, (d) followed person-centred working practices, and (e) were open to new ideas and suggestions from people outside of the team. The findings indicated that there were differences in culture between the underperforming and better performing group homes according to the five dimensions.

Drawing on the findings from Bigby and colleagues (Bigby & Beadle-Brown, Citation2016; Bigby et al., Citation2012), Humphreys et al. (Citation2020b) developed the Group Home Culture Scale (GHCS) to provide a quantitative measure of staff perceptions of culture. Using the GHCS, data from 23 group homes and multilevel modelling, Humphreys et al. (Citation2020a) examined dimensions of culture as predictors of QOL outcomes. They found that the GHCS dimensions of Effective Team Leadership and Alignment of Staff with Organisational Values significantly predicted residents’ engagement in activities, and the dimension of Supporting Well-Being significantly predicted residents’ community participation. They suggested that training and interventions that improved these dimensions of culture may potentially contribute to greater levels of engagement and community participation of people who live in group homes.

Gillett and Stenfert-Kroese (Citation2003) investigated the potential for accommodation services from the same organisation to differ in culture, which may account for differences in QOL outcomes for people with intellectual disabilities. They found that two services with similar structures, resources and resident characteristics differed significantly on three of 12 subscales on the Organizational Culture Inventory, a generic measure of culture; in the service with the more positive culture the residents had higher QOL outcomes. However, it is unknown how the culture in these two services compared to the other services within the organisation. Comparing culture across services has both theoretical and practical relevance.

From a theoretical stance, comparing culture across numerous group homes within organisations could test Martin’s (Citation1992, Citation2002) proposition that there are multiple perspectives of culture simultaneously evident in organisations. To guide conceptualisation and research of culture in organisations, Martin (Citation2002) proposed three perspectives of culture: integration, differentiation and fragmentation. From the integration perspective, culture is viewed as consistent and clear, with consensus throughout the organisation. From the differentiation perspective, clarity and consensus is instead found only among groups of staff or within subcultures. Thus, there may be numerous subcultures within an organisation and inconsistencies across them. Gillett and Stenfert-Kroese (Citation2003), for example, adopted the differentiation perspective, albeit implicitly, in that they hypothesised significant differences in culture between two accommodation services from the same organisation. In contrast, the fragmentation perspective suggests that culture is ambiguous, such that an identifiable culture is not discernible throughout an organisation or within staff groups. Of the three perspectives, the fragmentation perspective has been the most controversial, as it is at odds with the tradition of conceptualising culture as shared among group members (Trice & Beyer, Citation1993). To obtain a comprehensive understanding of an organisation’s culture, Martin (Citation2002) argued that researchers adopt all three perspectives simultaneously, because the culture in an organisation is likely to contain elements of each. Despite this recommendation, most researchers have studied culture from only one perspective (Kummerow & Kirby, Citation2014; Martin, Citation2002).

In addition to the theoretical implications, comparing culture across group homes within organisations has practical relevance by providing a basis from which service providers can determine the need for intervention either to change or maintain culture, and whether it should be provided either within specific group homes or across an organisation. For example, demonstration of poor culture in a group home compared with other group homes within an organisation may be indicative of problems with culture that warrants targeted intervention.

The purpose of the present study was to examine patterns of group home culture within disability organisations. Drawing on Martin’s (Citation2002) theory, the specific aim was to explore indications of both integrated and differentiated culture within organisations.

Method

Design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted of group homes for people with intellectual disabilities. A comparative, nonexperimental research design was used. Ethics approval for the study was provided by the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (S15/28).

Participants

Participants were a subset from the study by Humphreys et al. (Citation2020b). Participants were included in the present study if they worked as a disability support worker (DSW) or frontline supervisor in a group home that accommodated up to eight adults with intellectual disabilities, and three or more staff from the group home had completed the GHCS. Participants were excluded if they had worked in the group homes for less than 2 months and/or worked on average less than 4 hr per week.

The unit of analysis was the group home and data were available for 58 group homes managed by eight Australian nongovernment organisations. The organisations operated in three Australian states (New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia) and in both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas. presents the number of group homes managed by the organisations and the number participating in the study. Overall, data were available for 68% of the group homes managed by the eight organisations.

Table 1. Number of Total and Participating Group Homes for Eight Organisations.

The sample comprised 216 DSWs and 44 frontline supervisors (n = 260 staff) who worked across the 58 group homes. Participants were on average 44.2 years of age (SD = 13.1, range = 20–74), 67.1% were female and 54.4% were born in Australia. The majority of participants had either a Technical and Further Education Certificate 4 (30.7%; i.e., a vocational college qualification), Diploma (24.7%) or University Degree (16.3%) as their highest level of education. Most participants (81.1%) had worked in supported accommodation services for more than 3 years and their respective group homes for 1–2 years (26.4%), 3–5 years (24.4%), or 6–10 years (14.4%). Participants were employed on a full-time (46.8%), part-time (46.0%) or casual basis (7.2%). The majority of participants (60.5%) worked 31 hr or more per week in the group homes. The mean number of residents per group home was 5.1 and ranged from 3 to 7.

Measures

Group Home Culture Scale (GHCS)

The GHCS was used to measure staff perceptions of group home culture (Humphreys, Citation2018; Humphreys et al., Citation2020b). It is completed by DSWs and frontline supervisors. The GHCS comprises seven subscales, each of which have been found to have good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α range = .81–.92; Humphreys, Citation2018). presents descriptions and information about interpreting scores for the seven subscales. The GHCS consists of 46 itemsFootnote1 rated on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by strongly disagree (1) and strongly agree (5). Subscale scores for each group home are calculated by reverse scoring negatively phrased items, averaging item ratings, and then aggregating scores across staff members from the same group home (i.e., staff team). Subscale scores can range from 1.00–5.00. A higher score indicates more positive perceptions of the culture.

Table 2. Descriptions and Score Interpretations of the Group Home Culture Scale.

Demographic and employment information

Participants’ demographic and employment information were collected using a questionnaire included after the GHCS. This questionnaire comprised closed ended questions about age, gender, country of birth, highest level of education, experience working in supported accommodation services and the group home, and average hours worked.

Procedures

Questionnaire packets were provided to a manager or contact person at each participating organisation to be distributed to group home staff. Questionnaire packets comprised participant information statements, DSW and frontline supervisor questionnaires, and postage paid envelopes for completed questionnaires to be returned to the researchers. After the questionnaires were distributed, the contact person was asked to circulate two follow-up reminders to staff. Consent to participate was implied by the return of the questionnaire. Data were collected from October 2015 to February 2016.

Analyses

Data were entered into SPSS 25. Following checks for entry errors and missing values, descriptive statistics for the sample were calculated.

Missing data

An analysis of missing data was performed for the GHCS items for staff participants. There were missing data for 3.5% of participants for the subscale Supporting Well-Being, 0.8% for Factional, 1.2% for Effective Team Leadership, 4.6% for Collaboration within the Organisation, 1.5% for Social Distance from Residents, 2.3% for Valuing Residents and Relationships, and 3.8% for Alignment of Staff with Organisational Values. For participants with missing data, their score for the subscale was calculated by averaging the available item ratings (Newman, Citation2014), provided the number of missing items was within the thresholds suggested by Neill (Citation2008): allow one missing item per four to five items on a subscale, allow two missing items per six to eight items on a subscale, and allow three missing items per nine or more items on a subscale.

Interrater agreement and reliability

To justify aggregating individual staff members’ GHCS scores from the same group home (i.e., staff team), tests of interrater agreement and reliability were performed using rWG(J), and the intraclass coefficients ICC(1) and ICC(2) (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008). Taken together, rWG(J), ICC(1) and ICC(2) were used to estimate the extent to which perspectives of group home culture were shared by team members. A Microsoft Excel tool developed by Biemann et al. (Citation2012) was used to conduct the analyses.

The rWG(J) provided an index of agreement within teams (Bliese, Citation2000). An rWG(J) value was calculated for each team and a mean value across the teams was calculated. The values of rWG(J) range from 0 (complete lack of agreement) to 1 (complete agreement; LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008). Following Biemann et al.’s (Citation2012) recommendation, rWG(J) was calculated using a rectangular null distribution and another distribution based on theory. A slightly skewed null distribution was chosen because of the potential for a leniency response bias (Meyer et al., Citation2014). The rWG(J) values obtained using the rectangular null distribution were interpreted as the upper bound and those with the slightly skewed null distribution as the lower bound (Biemann et al., Citation2012).

ICC(1) was used to indicate the proportion of variance at the individual staff level that was attributed to team membership (Biemann et al., Citation2012). ICC(2) was used to estimate the reliability of the aggregate team scores (Biemann et al., Citation2012). ICC(2) is calculated as a function of ICC(1) and team size, with larger sized teams increasing reliability (Klein & Kozlowski, Citation2000).

Measures of dispersion

Patterns of GHCS scores were examined across group homes within the organisations from the integrated and differentiated perspectives. Integrated culture was defined as similarities in culture across group homes within an organisation. In contrast, differentiated culture was defined as variability in culture across group homes within an organisation. Hence, indicators of similarities and variability were visual inspection of scatterplots, ranges, and standard deviations in relation to mean scores (i.e., across homes participating from each organisation). Because of the small number of group homes in some organisations and the potential for non-normally distributed data, median scores have been reported in addition to mean scores. Analyses were conducted using SPSS 25.

Given the small size of the staff groups (i.e., teams), the data were deemed unsuitable for ANOVA to make comparisons within the organisations (M = 4.5, range = 3–8 staff participants). For example, a post hoc ANOVA power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., Citation2007) and data from the largest organisation, Organisation 8, where total sample size was 116 participants across 23 groups, alpha was set at .05 and effect size (ƒ) was set at .40, resulted in statistical power of .61. This level of power was less than the minimum of .80 as recommended by Cohen (Citation1992), indicating insufficient power to detect significant differences between groups. The data were deemed unsuitable for MANOVA because the sample size in each group was not greater than the number of dependent variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2014).

Results

Interrater agreement and reliability

shows the results of the tests for interrater agreement and reliability for the GHCS. The mean rWG(J) values using a rectangular null distribution ranged from .79 to .97 across the subscales, indicating strong (>.70) to very strong (>.90) agreement (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008). The majority of teams obtained strong to very strong levels of agreement across the subscales, although some teams were found to have low levels (rWG(J) < .70) on some subscales. Using a slightly skewed null distribution, the mean rWG(J) values ranged from .58 to .94 across the subscales, indicating moderate to very strong agreement (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008).

Table 3. Interrater Agreement and Reliability Indices for the Group Home Culture Scale (N = 58 Staff Teams).

ICC(1) values for the subscales ranged from .10 to .33, indicating that a moderate to large proportion of the variances were attributed to team membership (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008). ICC(2) values ranged from .33 to .69, which were less than the commonly accepted .70 level of reliability (Klein & Kozlowski, Citation2000), but are expected with small sized groups (Bliese, Citation1998). Ehrhart et al. (Citation2014) noted that ICC(2) values between .40 and .60 are common in research involving smaller sized groups. Only one GHCS subscale – Valuing Residents and Relationships – obtained an ICC(2) value below this range. Overall, the results of the rWG(J), ICC(1) and ICC(2) analyses indicated acceptable levels of interrater agreement and reliability, and that aggregation of individual staff level GHCS data to the team level was justified.

Descriptive statistics of the Group Home Culture Scale

shows the descriptive statistics of the GHCS across the 58 group homes. The lowest mean scores and largest variability were found on the Factional (M = 3.46, SD = .59, range = 1.86–4.79) and Collaboration within the Organisation subscales (M = 3.27, SD = .55, range = 1.78–4.38). In contrast, the highest mean score and smallest variability was found on Valuing Residents and Relationships (M = 4.29, SD = .27, range = 3.38–4.95).

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for the Group Home Culture Scale (N = 58 Group Homes).

Patterns of group home culture within organisations

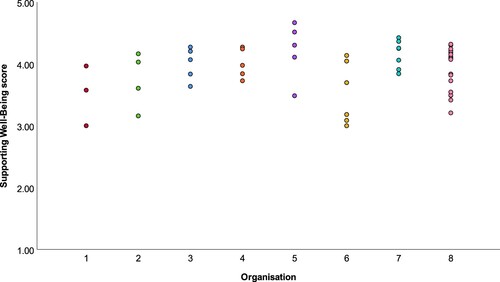

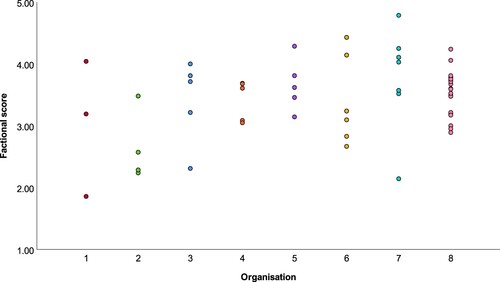

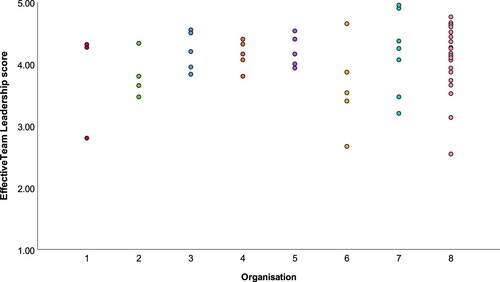

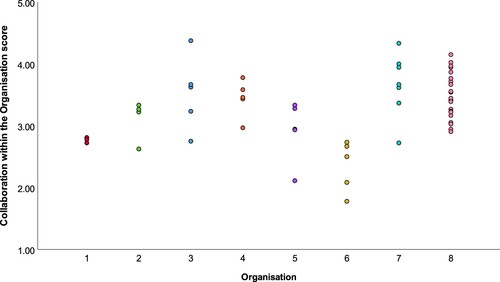

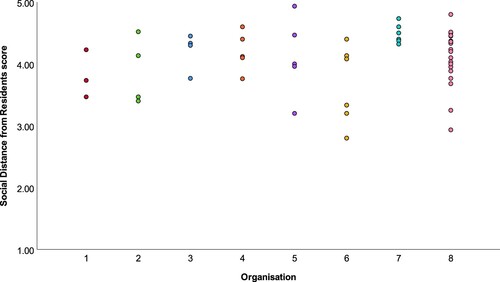

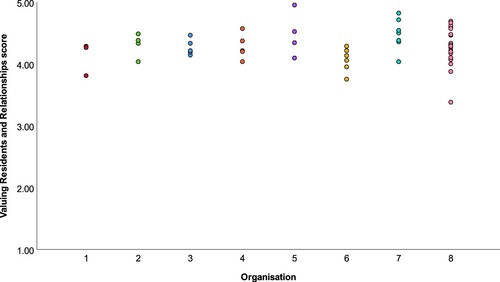

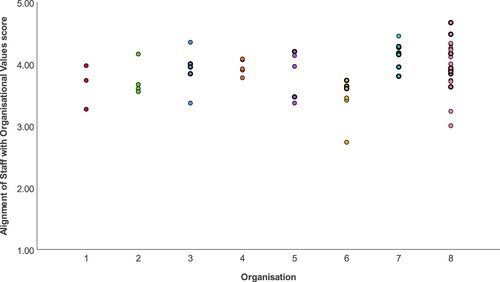

Patterns of integrated and differentiated culture were examined within the eight organisations for each subscale of the GHCS. Following inspection of scatterplots, the approximate criterion used for evidence of differentiation was range ≥ 1.50 and SD ≥ .5, and for integration was range ≤ .30 and SD ≤ .15. presents for each organisation and GHCS subscale the means, medians, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum scores.

Table 5. Group Home Culture Scale Scores for Eight Organisations (N = 58 Group Homes).

Inspection of scores for the subscale Supporting Well-Being in and showed there were no discernible patterns of integration or differentiation within the organisations. In contrast, inspection of and showed large variability and dispersion of scores across group homes in four organisations for the subscale Factional, indicating patterns of differentiation. These were in Organisations 1 (range = 1.86–4.04, SD = 1.10), 3 (range = 2.31–4.00, SD = .68), 6 (range = 2.67–4.43, SD = .72) and 7 (range = 2.14–4.79, SD = .84).

On the subscale Effective Team Leadership, variability was found within four organisations (). These were in Organisation 1 (range = 2.80–4.31, SD = .86), in which one home scored much lower than the other two homes, Organisation 6 (range = 2.67–4.65, SD = .65), Organisation 7 (range = 3.20–4.95, SD = .66) and Organisation 8 (range = 2.54–4.76, SD = .54).

Inspection of and showed there was variability across the five homes for Organisation 3 (range = 2.75–4.38, SD = .60) and the seven homes for Organisation 7 (range = 2.72–4.33, SD = .52) on the subscale Collaboration within the Organisation. In addition, similar low scores were found on this subscale across the three homes in Organisation 1 (M = 2.77, Mdn = 2.78, range = 2.72–2.81, SD = .04), indicating a pattern of integration.

On the subscale Social Distance from Residents, variability was found within three organisations (). These were Organisations 5 (range = 3.20–4.93, SD = .65) and 6 (range = 2.80–4.40, SD = .63), which met the criteria used as being indicative of differentiation, and also Organisation 8, which met the criterion for range (2.93–4.80), but only approximated that for SD (.42). Across the five homes in Organisation 3, similar scores (range = 4.14–4.46, SD = .13) were found on the subscale Valuing Residents and Relationships (). Inspection of and showed that on the subscale Alignment of Staff with Organisational Values there were similar scores across the five homes in Organisation 4 (range = 3.78–4.08, SD = .13). Also on this subscale, variability was found across the 23 homes in Organisation 8, which met the criterion for indication of differentiation for range (3.00–4.67), but not SD (.38).

Discussion

In the present study, patterns of culture from the integration and differentiation perspectives were examined in 58 group homes managed by eight organisations. It extended on Gillett and Stenfert-Kroese’s (Citation2003) study by examining culture across numerous group homes and organisations, and from two theoretical perspectives based on the work of Martin (Citation2002).

Examining culture from the differentiation perspective showed that within six of the organisations there were patterns indicative of differentiated culture for one or more GHCS subscales. For example, in Organisation 7, variability was found across the participating group homes for three subscales. Further exploration revealed that one group home in this organisation had relatively high scores on these three subscales, whereas another had relatively low scores, indicating differences in culture between these two homes. Differentiated culture may develop for a number of reasons, including because group homes are often geographically dispersed and staff who work in group homes may have differential interactions, shared experiences and similar personal characteristics, each of which can contribute to shared beliefs, values, norms and practices (Trice & Beyer, Citation1993). Also, there is potential for staff teams to report to and be influenced by different senior managers, which could contribute to the differentiation of culture across group homes operated by the same organisation.

In contrast, examining culture from the integration perspective showed that within three of the organisations there were patterns indicative of integrated culture for one GHCS subscale. In Organisation 4, for example, there were similar scores across the five group homes for the subscale Alignment of Staff with Organisational Values. Patterns consistent with integration demonstrates that there can be similarities in culture across group homes from the same organisation. An integrated culture may develop through common staff experiences (Van Maanen & Barley, Citation1985), aligning staff teams to certain values, beliefs and norms, and encouraging common ways of working (Schein, Citation2010).

Examining culture from the integration and differentiation perspectives simultaneously showed that within two of the organisations – Organisations 1 and 3 – there were patterns indicative of integrated and differentiated culture for some of the GHCS subscales. In Organisation 3, for example, where data for all five group homes were available, a pattern indicating integration was found on the subscale Valuing Residents and Relationships, while patterns indicating differentiation were found on the subscales Factional and Collaboration within the Organisation. These results suggest that in this organisation, the group homes were not simply integrated with the wider organisation or differentiated from each other. Rather, simultaneous elements of integration and differentiation for some dimensions of group home culture seemed likely. Therefore, adopting both perspectives offered greater insight into culture than would be obtainable from a single perspective.

Examination of staff perceptions of culture suggested potential concerns in some group homes about perceived organisational support and priorities, as indicated by the relatively low scores on the subscale Collaboration within the Organisation. In previous research, it has similarly been found that staff can feel distanced from senior managers and the broader organisation (Bigby et al., Citation2012; Ford & Honnor, Citation2000). Given that group homes are typically geographically dispersed and distanced from an organisation’s central office, it seems understandable that staff can feel separated from senior management. Previous research suggests that key issues include: (a) a perceived lack of understanding by senior managers of what it is like to work on the frontline (Bigby et al., Citation2012); (b) a lack of organisational support to perform their role (Ford & Honnor, Citation2000); and (c) a lack of staff involvement in decision making (Ford & Honnor, Citation2000; Quilliam et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, a lack of senior management involvement in service delivery may impact not only staff but also residents, as found in studies of accommodation services in which there have been allegations of staff abuse of residents (Cambridge, Citation1999; Marsland et al., Citation2007; White et al., Citation2003). Despite these common findings across studies, the characteristics of effective collaboration between senior managers and staff, which will enhance service delivery and staff members’ satisfaction, remain areas that have received scant research attention. Although recent research has explored the practices of senior managers that influence frontline service delivery (Bigby et al., Citation2020; Deveau et al., Citation2020).

Another dimension of culture that has received scant research attention relates to staff factions, measured in this study on the Factional subscale. Across the sample, the second lowest mean scores were found on this subscale, indicating that in some group homes, there was a perception that some staff had a detrimental influence on team dynamics. Given the potential prevalence of factions within teams, how they are managed would seem important. Frontline supervisors are likely to be responsible for managing factions because enhancing staff relations and managing staff comprise their key competencies (Clement & Bigby, Citation2012). Despite this role, there appears to be a lack of information available to frontline supervisors about how to effectively meet these competencies, particularly how to manage factions and conflict within teams, and facilitate teamwork.

An unexpected result was the high mean score and small variability found across the sample for the subscale Valuing Residents and Relationships. This finding indicates that most staff teams perceived that they valued the residents and the relationships they had with them. Valuing residents and relationships could be considered, to some extent, a common characteristic of the culture across most of the group homes. In previous studies, researchers have found that interactions with residents provided frontline staff with the greatest satisfaction in their role (Ford & Honnor, Citation2000), and staff valued the relationships they had with residents to the extent that it could be considered a motivating factor for working in their role (Hermsen et al., Citation2014).

Practice implications

The current research has identified patterns of integrated and differentiated culture within the organisations, which may inform decisions about whether interventions to change or maintain culture are warranted and whether they should be targeted to specific group homes or to the whole organisation. For instance, similar low scores within an organisation (i.e., integrated culture) for a subscale may indicate a whole of organisation issue requiring organisation-wide interventions to change culture. On the other hand, comparatively lower scores on a subscale for one or more group homes, than for others within the organisation (i.e., differentiated culture), could indicate that interventions are best targeted to specific group homes. In contrast, group homes with comparatively higher scores may need to implement strategies to maintain culture. Interventions are also potentially warranted in group homes with lower scores across multiple GHCS subscales, which may be indicative of a poor quality culture. More specifically, the findings from Humphreys et al. (Citation2020a) suggest that interventions that enhance Effective Team Leadership and Supporting Well-Being may potentially increase residents’ levels of engagement and community participation, respectively.

Limitations and directions for future research

Drawing conclusions from this study requires caution because patterns of culture were examined using scatterplots and measures of dispersion. The small sized groups precluded valid use of inferential statistics that would determine whether the magnitude of differences reached significance (Maxwell & Delaney, Citation2004; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2014). The lack of inferential statistics means that the results of this study are not generalisable. Further testing with larger group sizes to allow for inferential statistics is required, however, such testing is likely to be difficult because staff teams working in group homes are typically small. Nonetheless, the analysis used in this study was deemed useful in examining patterns of integrated and differentiated culture. The criterion used for evidence of patterns of integrated and differentiated culture requires replication with other datasets to determine the consistency with which the range of ≥ 1.50, either alone, or with a standard deviation of ≥ .5 indicates variability, and therefore its application as a rule of thumb.

Another limitation of this study was that for seven organisations data were available for half or most of the group homes, but not all, which precluded definitive assessment of the extent to which culture was integrated and differentiated within the organisations. Although procedures were followed to maximise the number of returned staff questionnaires, in future research, an electronic questionnaire could also be administered (i.e., mixed mode questionnaire administration; see Dillman et al., Citation2014) to increase the number of participants.

The finding that some staff teams have a more positive culture than others, as indicated by higher scores, presents an opportunity for further research into identifying the factors that contribute to positive team culture. Potential factors may include the personal characteristics and work experience of staff, the type and frequency of interactions among team members, and the personal characteristics of residents. Such research could have implications for the composition and functioning of staff teams.

Conclusion

The findings from this study contribute to the conceptualisation of organisational culture in supported accommodation services for people with intellectual disabilities by showing patterns suggestive of group home culture being integrated and differentiated within organisations. Understanding culture in group homes and how to deliver interventions to change or maintain it may contribute to enhancing service quality and QOL outcomes for people with intellectual disabilities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The 46 item version of the GHCS reported by Humphreys (Citation2018) was used in the present study.

References

- Biemann, T., Cole, M. S., & Voelpel, S. (2012). Within-group agreement: On the use (and misuse) of rWG and rWG(J) in leadership research and some best practice guidelines. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.006

- Bigby, C., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2016). Culture in better group homes for people with intellectual disability at severe levels. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 54(5), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-54.5.316

- Bigby, C., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2018). Improving quality of life outcomes in supported accommodation for people with intellectual disability: What makes a difference? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(2), e182–e200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12291

- Bigby, C., Bould, E., Iacono, T., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2020). Quality of practice in supported accommodation services for people with intellectual disabilities: What matters at the organisational level. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 45(3), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2019.1671965

- Bigby, C., Knox, M., Beadle-Brown, J., Clement, T., & Mansell, J. (2012). Uncovering dimensions of culture in underperforming group homes for people with severe intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(6), 452–467. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.06.452

- Bliese, P. D. (1998). Group size, ICC values, and group-level correlations: A simulation. Organizational Research Methods, 1(4), 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814001

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein, & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

- Braddock, D., Emerson, E., Felce, D., & Stancliffe, R. J. (2001). Living circumstances of children and adults with mental retardation or developmental disabilities in the United States, Canada, England and Wales, and Australia. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 7(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.1016

- Cambridge, P. (1999). The first hit: A case study of the physical abuse of people with learning disabilities and challenging behaviours in a residential service. Disability & Society, 14(3), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599926154

- Clement, T., & Bigby, C. (2010). Group homes for people with intellectual disabilities: Encouraging inclusion and participation. Jessica Kingsley.

- Clement, T., & Bigby, C. (2012). Competencies of front-line managers in supported accommodation: Issues for practice and future research. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2012.681772

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Deveau, R., Gore, N., & McGill, P. (2020). Senior manager decision-making and interactions with frontline staff in intellectual disability organisations: A Delphi study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12842

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th ed.). Wiley.

- Ehrhart, M. G., Schneider, B., & Macey, W. H. (2014). Organizational climate and culture: An introduction to theory, research, and practice. Routledge.

- Emerson, E., Hastings, R., & McGill, P. (1994). Values, attitudes and service ideology. In E. Emerson, P. McGill, & J. Mansell (Eds.), Severe learning disabilities and challenging behaviours: Designing high quality services (pp. 209–231). Chapman & Hall. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2961-7_9

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Felce, D., Lowe, K., & Jones, E. (2002). Staff activity in supported housing services. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 15(4), 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2002.00130.x

- Ford, J., & Honnor, J. (2000). Job satisfaction of community residential staff serving individuals with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 25(4), 343–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250020019610

- Gillett, E., & Stenfert-Kroese, B. (2003). Investigating organizational culture: A comparison of a ‘high’- and a ‘low’-performing residential unit for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(4), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00170.x

- Hartnell, C. A., Ou, A. Y., & Kinicki, A. (2011). Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of the Competing Values Framework's theoretical suppositions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 677–694. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021987

- Hastings, R. P., Remington, B., & Hatton, C. (1995). Future directions for research on staff performance in services for people with learning disabilities. Mental Handicap Research, 8(4), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.1995.tb00165.x

- Hermsen, M. A., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Hendriks, A. H. C., & Frielink, N. (2014). The human degree of care. Professional loving care for people with a mild intellectual disability: An explorative study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(3), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01638.x

- Humphreys, L. (2018). Does organisational culture matter in group homes for people with intellectual disabilities? La Trobe University. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.9/565789

- Humphreys, L., Bigby, C., & Iacono, T. (2020a). Dimensions of group home culture as predictors of quality of life outcomes. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(6), 1284–1295. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12748

- Humphreys, L., Bigby, C., Iacono, T., & Bould, E. (2020b). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Group Home Culture Scale. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(3), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12693

- Klein, K. J., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2000). From micro to meso: Critical steps in conceptualizing and conducting multilevel research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(3), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810033001

- Kummerow, E., & Kirby, N. (2014). Organisational culture: Concept, context, and measurement. World Scientific.

- LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

- Mansell, J., Beadle-Brown, J., & Special Interest Research Group. (2010). Deinstitutionalisation and community living: Position statement of the comparative policy and practice Special interest research group of the International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(2), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01239.x

- Mansell, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2012). Active support: Enabling and empowering people with intellectual disabilities. Jessica Kingsley.

- Marsland, D., Oakes, P., & White, C. (2007). Abuse in care? The identification of early indicators of the abuse of people with learning disabilities in residential settings. The Journal of Adult Protection, 9(4), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/14668203200700023

- Martin, J. (1992). Cultures in organizations: Three perspectives. Oxford University Press.

- Martin, J. (2002). Organizational culture: Mapping the terrain. Sage.

- Maxwell, S. E., & Delaney, H. D. (2004). Designing experiments and analyzing data: A model comparison perspective (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

- Meyer, R. D., Mumford, T. V., Burrus, C. J., Campion, M. A., & James, L. R. (2014). Selecting null distributions when calculating rwg: A tutorial and review. Organizational Research Methods, 17(3), 324–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114526927

- Neill, J. (2008, 2016). Psychometric instrument development. Lecture 6: Survey research & design in psychology. Retrieved 29/05/2016 from http://www.slideshare.net/jtneill/psychometric-instrument-development-reliabilities-and-composite-scores

- Newman, D. A. (2014). Missing data: Five practical guidelines. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 372–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114548590

- Quilliam, C., Bigby, C., & Douglas, J. (2018). Being a valuable contributor on the frontline: The self-perception of staff in group homes for people with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(3), 395–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12418

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2014). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Trice, H. M., & Beyer, J. M. (1993). The cultures of work organizations. Prentice Hall.

- Van Maanen, J., & Barley, S. R. (1985). Cultural organization: Fragments of a theory. In P. J. Frost, L. F. Moore, M. R. Louis, C. C. Lundberg, & J. Martin (Eds.), Organizational culture (pp. 31–53). Sage.

- Wardhaugh, W., & Wilding, P. (1993). Towards an explanation of the corruption of care. Critical Social Policy, 13(4), 4–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101839301303701

- White, C., Holland, E., Marsland, D., & Oakes, P. (2003). The identification of environments and cultures that promote the abuse of people with intellectual disabilities: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(1), 1–9. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00147.x