ABSTRACT

Background

Many people with disability experience harm in everyday interactions that can leave them feeling insulted, degraded, silenced, or rejected. We adopt the term “everyday harm” to describe this underexplored form of harm.

Method

The purpose of this scoping review was to assess how the literature on microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse contributes to an understanding of everyday harm and misrecognition.

Results

Microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse occur at an interpersonal level and are influenced by organisational structures and attitudes, underpinned by ableist attitudes and stigma. Actions and omissions are both intentional and unintentional and the effects are subjective and cumulative.

Conclusion

Insights from microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse can inform the concept of everyday harm. Little is known about how people with disability understand and respond to their harmful experiences and everyday harm can offer a language to name and prevent this form of harm.

This article presents findings from a scoping review of literature on microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse, relating to disability. The purpose of the review is to inform a multi-method study that uses the term “everyday harm” to describe the subtle, common, often unacknowledged, yet frequent harm that many people with cognitive disabilityFootnote1 experience daily. As this term appears to not have been used in a research context, the scoping review was completed to generate evidence to support its use or not. Earlier empirical research (Robinson et al., Citation2022) informed by recognition theory (Honneth, Citation1995) is used alongside microaggression theory to contextualise the scoping review.

The scoping review method and results are presented in this article. A series of implications for people with cognitive disability are identified and discussed, with particular focus on those people who use paid support.

Everyday harm and recognition theory

Recent commissions of inquiry, including the Australian Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (Citation2023), have appropriately focused on abuse and violence toward people with disability. Nevertheless, more subtle and difficult to name harm is often overlooked.

Everyday harm is a concept developed through earlier empirical research (Robinson et al., Citation2022) informed by recognition theory (Honneth, Citation1995). For this article’s purposes, everyday harm encompasses interactions between people that are received as hurtful or harmful and may cause people to feel insulted, degraded, excluded, rejected, threatened, or silenced. The harm can be intentional or unintentional, result from actions or omissions or inaction, and can often have a cumulative negative effect. Although felt on a personal level, everyday harm is often formed and influenced by organisational policies and practices. This harm might also constitute warning signs of problems about safety and wellbeing in relationships, or indicate potential violence and abuse (Robinson et al., Citation2022).

Recognition theory explains that a person’s sense of self, wellbeing, and value is connected to their experiences with others and the attitudes expressed by others towards them. Three modes of love (or care), respect, and esteem form the basis for harmonious relationships and positive identity formation (Honneth, Citation2004). Simply explained, “recognition from others supports the development and maintenance of a person’s positive self-identity, and … this is important for her/his capacity for agency and flourishing life in the world with others” (Robinson et al., Citation2022, p. 4). Recognition theory helps in understanding the messy, complex interactional work of paid disability support relationships. Its inverse, misrecognition, may be important in understanding and preventing everyday harm, through its attention to lack of care, disrespect, and devaluing in human relationships (Robinson et al., Citation2022).

Developing a better understanding of everyday harm presents opportunities to improve the quality of support between people with disability and paid support workers. This is important for people with cognitive disability, who experience both a high number of formal relationships with paid workers and a disproportionately high rate of abuse (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, Citation2023). Research with young people with cognitive disability and their support workers has confirmed the need to pay more attention to slights, insults, disrespect, and other forms of misrecognition in daily interactions that arise from interpersonal or institutional acts, or both, and attitudes (Robinson et al., Citation2022). These casual forms of harm, behaviours outside of reportable conduct codes, are often ignored or overlooked and their impact can be damaging.

Porter et al. (Citation2022) identified the complexity of paid relationships that are embedded forms of work, involving both social and economic interactions and dependent on trust. They hold potential for trouble within the relationship and risks of misrecognition. These relationships sit within the dynamic of larger socio-ecological structures (institutions). These structures are formed by policies and practices that should facilitate recognition through acknowledgement of people’s rights, preventing everyday harm, and responding appropriately when harm occurs (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, Citation2023).

Understanding microaggression

Microaggression is a concept closely related to everyday harm. It arises from racism scholarship, which focuses on the micro or common actions of discrimination (Sue et al., Citation2008). Unlike intentional discrimination, microaggressions are everyday actions that might be unconscious, or unintentional acts of discrimination. Torino et al. (Citation2019), building on Sue’s (Citation2010) earlier work, explained microaggressions as acts of everyday exchange that send denigrating messages to certain people because of their group membership. They posit that microaggressions are not always intended or conscious, but rather illustrate a person’s world perspective, with the microaggressor operating from a position of power or privilege in their everyday interactions.

Microaggression theory describes three forms (Sue et al., Citation2008). Microinsults may be unintentional and are marked by insensitivity toward the person’s identity, including presumptions about capacity and qualifications. Microinvalidations overlook a person’s lived experience based on their identity, through dismissive responses to their experiences based on membership of the target group, for example, a person of colour, disability, or LGBTQAI + . Microassaults are blatant expressions of discrimination with clear negative intent and include derogatory language, “similar to old-fashioned racism” (Torino et al., Citation2019, p. 4).

Scholars agree on a general definition of microaggression, but with some differences. For example, Torino et al. (Citation2019) defined microaggression at the interpersonal level and distinguish it from macroaggression attributed to institutional bias in policies that reinforce discrimination. However, others use microaggression to describe actions and omissions that occur at both interpersonal and institutional levels (Ellem et al., Citation2020; Eun-Jeong et al., Citation2019).

Scholars have noted the effects of microaggression, the complexity of experiences, and the negative impact on the recipient’s quality of life (Eun-Jeong et al., Citation2019; Keller & Galgay, Citation2010; Owen et al., Citation2019; Wayland et al., Citation2022). They theorise that intentionality and “felt harm” are not necessarily consistent. An action can be “unintentional, subtle, covert, and innocuous”, while the consequence is “experienced as jarring, overt, and harmful” (Sue et al., Citation2008, p. 329).

Microaggressions and their effects are enacted in a sequence of events and responses that stem from one or many incidents. The steps can involve perception – the recipient questions what happened; then, reaction – the recipient seeks to understand the “hidden meanings” of what happened. They may self-reflect or ask others to make sense or validate their experience. This leads to interpretation – the person derives an invalidating or negative meaning from the incident such as, “you don’t belong”, “your way is wrong”. This is followed by the consequences of microaggression – the impact felt by the person on both a single occasion and with cumulative effect (Sue et al., Citation2008). These feelings may leave the person feeling “unimportant, invisible and misunderstood” (Keller & Galgay, Citation2010, p. 258).

People with disability experience microaggressions not experienced by non-disabled people through ableist discriminatory practices. Keller and Galgay (Citation2010) identified eight domains in their Disability Microaggressions of Everyday Life (DMEL) taxonomy. These are denial of identity (the person is seen only through their disability or denial of disability experience), denial of privacy (personal information about disability is required), helplessness (receiving unwanted “help”), secondary gain (others feel good doing something for a person with disability), spread effect (all parts of a person are “assumed to be due to a specific disability”), patronisation (including infantilisation), second-class citizen (rights and equality are denied), and desexualisation (sexuality and sexual being denied) (Keller & Galgay, Citation2010, pp. 249–250). The taxonomy’s domains resonate with recognition theory in that these experiences are constitutive of personhood.

Emotional and psychological abuse

Emotional and psychological abuse also resonates with misrecognition theory in its effects on a sense of valued and dignified personhood. Women with Disabilities Australia (WWDA) defined emotional and psychological violence as:

The infliction of anguish, pain, or distress through verbal or non-verbal acts and/or behaviour. It results in harm to a person’s self-concept and mental well-being as a result of being subjected to behaviours such as verbal abuse, continual rejection, withdrawal of affection, physical or social isolation and harassment, or intimidation. (Women with Disabilities Australia, Citation2007, p. 33)

Like microaggression theory, frameworks for understanding emotional and psychological abuse have been developed about groups who experience high rates of harm and are structurally oppressed by power dynamics. Robinson and Chenoweth’s (Citation2012) framework for people with intellectual disability positions misuse of power and control at its centre, with eight thematic areas: degrading; terrorising; corrupting/exploiting; isolating; caregiver privilege; minimising, justifying and blaming; and withholding, misusing and delaying needed supports. Hayashi’s (Citation2022) scoping review adopted a conceptual framework of abstract, operational and professional standards to define and acknowledge these forms of abuse relating to children.

According to these frameworks, emotional and psychological abuse is manifest through components associated with abuser and victim characteristics, through an action or inaction, with other aspects of frequency, intention, consequences, and interaction. These frameworks emphasise the connection between the interpersonal aspect of emotional and psychological abuse and the context that influences and drives it (Robinson & Chenoweth, Citation2012).

Method

The scoping review analysed literature on microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse of people with disability to situate our conceptualisation of everyday harm in the literature. A scoping review takes a broad approach to map “rapidly the key concepts underpinning” a research focus and to establish gaps in the existing literature (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005, p. 21). The research question was: how does the evidence about microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse contribute to an understanding of everyday harm and misrecognition of people with disability? As our concepts are both new to use in research (everyday harm) and specific (cognitive disability), an interpretation of the wider evidence about microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse relating to people with disability is needed. The implications are useful for policy and practice, and for considering whether there is merit in further exploration through empirical research.

Review process

Searches were conducted in five databases – SCOPUS, Proquest, APAFT, CINAHL, and Taylor & Francis online. Manual searches were also conducted of four relevant journals: Disability and Society, Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, British Journal of Learning Disability, and Journal of Family Violence. The search parameters were the presence of keywords in the article title or abstract in peer-reviewed articles and book chapters in English published in the past 5 years (January 2017 – December 2022), deemed an appropriate time frame to return an adequate response and prioritise contemporary research. The keyword search terms used were combinations of abuse, disability, and microaggression variants:

Microaggression AND safety

Microaggression AND disability OR disabilities OR disabled disabil*

Microaggression AND intellectual disability OR mental retardation OR learning disability OR developmental disability OR learning disabilities

Microaggression And emotional and psychological abuse OR neglect OR abuse or mistreat* OR maltreat* AND disabil*

Emotional and psychological abuse AND safety

Emotional and psychological abuse AND neglect OR abuse OR mistreat* OR maltreat* AND disabil* OR disability OR disabilities OR disabled

Emotional and psychological abuse AND neglect OR abuse OR mistreat* OR maltreat* AND intellectual disability OR mental retardation OR learning disability OR developmental disability OR learning disabilities

Emotional and psychological abuse AND disabil* disability OR disabilities OR disabled

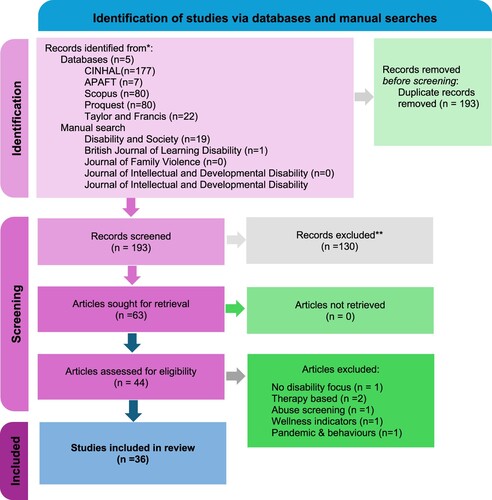

The searches identified 193 articles (excluding duplicates). Preliminary review of titles by two researchers excluded clinical and therapy-based studies, and articles that did not refer to people with disability. No academic theses (n = 5) met the criteria for inclusion. Two researchers conducted title and abstract review of remaining 63 articles using Covidence software. Review consensus was good to high with 44 articles (database n = 35, manual n = 9) relevant for full-text review. The articles were imported into NVivo software for full-text review and analysis. During full-text review and analysis eight articles were excluded as these did not focus on the concepts in the research question. See PRISMA diagram (Page et al. Citation2021).

Figure 1. PRISMA Everyday harm experienced by people with cognitive disability – a scoping review of microaggression, emotional and psychological abuse.

The final 36 articles included in this review are shown in , which provides information about the author, year, population focus, method, and summary of the relevance to the concept of everyday harm. The analytical framework focused on the searched keywords in addition to and alongside the three modes of misrecognition (lack of care, respect, or value) and the organisational context (Honneth, Citation1995).

Table 1. Reviewed articles.

Results

The findings include an overview of the articles, the focus, and type of study, followed by three themes drawn from analysis of the articles. The first theme explores how the literature applied microaggression theory to understand harmful behaviours, actions, and omissions toward people with disability. The second theme focuses on everyday experiences of harm of people with disability at interpersonal, organisational, and structural levels. The third theme reflects ableist attitudes in organisations and wider communities, seen in stereotyping of and stigma toward people with disability. Articles are noted with numbers identified in , unless quoted.

A greater number of articles focused on disability and microaggression than on disability and safety, or on emotional and physical abuse. Microaggression was discussed in 21 of the 36 articles, with many referring to Sue et al.’s (Citation2008) research on microaggression and racism (n = 19), Keller and Galgay’s (Citation2010) Disability Microaggressions of Everyday Life (DMEL) taxonomy (n = 16), or a more recent discussion of microaggression by Torino et al. (Citation2019) (n = 9). Six of the 13 articles that discussed emotional and psychological abuse had these concepts as a focus (17, 25, 29, 30, 35, 36); two described them as a direct impact of microaggression (8, 34); and five considered them forms of microaggression (3, 8, 9, 32, 34). Twelve articles referred to safety, although in five, it was mentioned only in passing. Other articles addressed organisational practices and safety (1, 35); abuse and safeguarding (10, 17); the impact of a lack of accessible, affordable, and appropriate health care for women (25); safe environments for para-athletes to train and compete (30); staff development and the health and safety of people with intellectual disability (16); and the impact of emotional and psychological abuse on the erosion of a person’s sense of wellbeing and safety (36).

Study methods in the 36 articles were qualitative (n = 19), quantitative (n = 7), mixed method (n = 4), ethnographic (n = 2), a systematic review (n = 2), historical analysis (n = 1), and a narrative inquiry (n = 1). The population focus for these studies was mainly people with specific disability and some articles included multiple populations ().

Table 2. Number of articles per population focus.

Microaggression, emotional and psychological abuse, and disability

Microaggression theory was applied to disability in ways consistent with misrecognition theory and the concept of everyday harm. Some scholars included emotional and psychological abuse within the umbrella of microaggression, and the review found similar themes to those identified in the microaggression literature.

Many articles about microaggression and disability applied the domains in Keller and Galgay’s (Citation2010) DMEL taxonomy. These domains reflected the everyday harm of misrecognition in situations and relationships where people were not cared for, respected or valued, at interpersonal and organisational levels. The authors emphasised tensions around intentionality and interpretation, that is, whether people understood the action as hurtful.

Three articles engaged in depth with Keller and Galgay’s (Citation2010) DMEL taxonomy. Canel-Çinarbaş et al. (Citation2022) outlined 10 domains or themes (italics), with some DMEL taxonomy domains subsumed as categories of a broader domain. Additional domains were alienation, overt discrimination, and systemic discrimination. The latter two domains are useful for our study to develop an understanding of everyday harm situated in organisational practices and policies. Conover et al.’s (Citation2017) study outlined the development and validation of four domains that make up the ableist microaggression scale, which are based on DMEL. The domains were: helplessness – “individuals with disabilities being treated as if they are incapable, useless, dependent, or broken, and imply they were unable to perform any activity without assistance”; minimisation – suggestions were that people with disability were overstating their needs or impairment and a level of belief that they could be able-bodied if they wanted to be, denial of identity; denial of personhood – encompasses desexualisation, the spread effect where assumptions about ability were reduced to “one’s physicality”, second-class citizen, denial of privacy, patronisation, and otherisation – being treated as “abnormal, an oddity, or nonhuman” the implication being that people with disability were not “natural” (Citation2017, p. 581). Miller and Smith (Citation2021, p. 493) added to the DMEL taxonomy, microaggressions concerned with heteronormative institutional and structural ableism, and “forms of environmental microaggression”. Respondents described situations where they adopted actions to protect themselves such as “queer passing” and “ableist avoidance”. Studies drawing on emotional and psychological abuse discussed perceptions of abuse in general, specific abuse (e.g., bullying), and poor practice in different contexts. They did not engage with emotional and psychological abuse frameworks in the same way as the microaggression and disability literature.

Intention to harm

Microaggressive acts were described in many studies (n = 20) and included intentional (n = 20) and unintentional harm (n = 9) (3, 7, 11, 13, 19, 20, 31). The ambiguity about intention in microaggression was identified in several articles (2, 5, 6, 13, 31, 34). Similarly, a lack of shared understanding of what constituted an emotional or psychological harm was noted in several articles (10, 25). Schroer and Bain suggested that while microaggressive acts may be ambiguous, the reception or impacts were not and it was valuable to move away from a focus on the microaggressive acts (of the perpetrator) and conceptualise microaggression “from the perspective of those targeted” (Citation2020, p. 230).

In summary, microaggressions were conceptualised as interactions based in discrimination, which could be inadvertent, direct, or subtle and everyday. The interactions demonstrate misrecognition through lack of care, respect and valuing the individual. Inadvertent or unconscious bias rooted in daily interactions might also reflect what could be construed as overt or organisational discrimination (6), explored later in the findings.

Experiencing and understanding harm

The routine occurrence of microaggression, emotional and psychological abuse in the lives of people with disability explored in these articles illustrated the ambiguities of everyday harm. While some forms of abuse clearly show lack of care and respect for people with disability (25, 35), aspects of “poor practice” and some ableist microaggressions were not easily deciphered or consistently acknowledged (17, 31). Microinsults and invalidations could contain positive and negative messages simultaneously (21). For example, a comment might pass as a compliment, but could be received as insulting or an intended helpful act that is unrequested or unwanted, perceived as infantilising (2, 34). Personal identity was challenged when judged by others as “not disabled enough” (21, 31). Jokes and games that subtly undermined the person’s capacity, authority, and self-esteem were both microinsults (36) and forms of emotional and psychological abuse (35). The ambiguity of whether an action was felt or understood as harmful could cause self-doubt in the person (5). Schroer and Bain (Citation2020, p. 242) termed this “oppressive epistemologies of harm”.

Several authors argued that “indirect and subtle expressions of discrimination are difficult to detect, yet their effect is just as harmful as the direct expressions of discrimination” (Canel-Çinarbaş et al., Citation2022, p. 47) and “can still have a negative impact” (Eun-Jeong et al., Citation2019, p. 189). Wayland et al. argued that microaggressions “are acts that are not violent per se, but the everyday accumulation over time leads to the internalisation of self-loathing and accretion of harm” (Citation2022, p. 868).

This ambiguity of microaggressions, especially concerning intent, often placed an onus on the person with disability to decide whether to challenge or overlook the microaggressive act or omission (20). Coalson et al. (Citation2022) found that people who stutter preferred to “exonerate” the speaker and give them the benefit of the doubt. The ambiguity also raised questions about other people’s responsibility to act when they noticed microaggressions.

Harm as an everyday experience

The second theme was that the harm described in the reviewed literature is an “everyday” experience for people with disability across their life domains. The everyday was evident at the interpersonal and the organisational level, where it was attributed to organisational practices, policies and culture, systemic failures, and inadequate worker training (16).

Interpersonal everyday harm

Most of the literature included examples of experiences of microaggressions and emotional and psychological abuse in personal interactions. These included being ignored, insulted, excluded from participation or denied agency (18), being stared at or prayed over, touched, helped (without consent), or having one’s body policed (2, 3, 15, 19, 20, 33, 34). These harms occurred when a support worker “plays games” or disrespects possessions (35), or engages in name-calling, or when bystanders overlook public victimisation and violence (3, 11, 13, 23, 31, 36). Other harms included being patronised or infantilised (5, 11, 12), judged by strangers (33, 34); and having their identity disputed or overlooked (24, 34), their rights denied and being treated as second-class citizens (13, 14, 15, 18, 33). For some people, harm occurred when close family denied or disregarded their experiences (2, 9, 20, 33). Sullivan (Citation2021, p. 9) noted that despite the political focus and public demand to ensure the rights and inclusion of people with disability, policies appear to “have had little impact on actual day to day experiences of neurodivergent individuals”.

Harm at organisational levels

The literature conceptualised organisational harm through workplace culture, and workers’ attitudes. Examples of organisational microaggressions and emotional and psychological abuse resulted from formal and informal norms that prevented participation, or failures in policies, staff training, and organisational management to respect a person’s rights (17). Microaggressions at organisational levels were enacted by people producing and reproducing power dynamics. Often hostile organisational cultures existed in “the mundane enactments of ableist prejudice and privilege” that reflected “broader socio-cultural relationships of power, while also being a profoundly personal, relational and embodied experience” (Calder-Dawe et al., Citation2020, p. 135).

Organisational cultures were host to microaggression in interactions between the organisation, its representative or worker, and the person with disability. Calder-Dawe et al. (Citation2020) argued that microaggression in medical diagnosis and treatment arose through how the body was seen. Organisational harm included clinical misdiagnoses (20); health care workers’ lack of knowledge about the condition (25), stigma and failure to provide adequate care or withholding care (8); “withholding medication, restrictive practices and neglect” (Cortis & Van Toorn, Citation2022, p. 199); patronisation (5): and infantilisation, when workers withheld or neglected to provide information to the person with disability (12).

Organisational practices that caused microaggression in interpersonal relationships functioned as part of a political system (31) and sociocultural norms (17). Miller and Smith (Citation2021) described environmental microaggression experiences of LGBTQAI + populations where organisations failed to accommodate, value, and care for people with disability and their intersecting identities.

Workplace microaggressions included assumptions about a person’s capacity to perform their role, an example of the spread effect where cognitive disability was assumed due to the presentation of stuttering (5); and having their rights, agency, and self-determination undermined by support workers’ and others’ actions and attitudes (18). Common experiences were marginalisation and harassment, that equated disability with incompetence or helplessness (3). Workers’ attitudes may reflect organisational culture and have a direct impact on people’s experiences. Undermining attitudes in paid relationships with young people appear uncaring, and affected their trust in organisations (12). These microaggressions may negatively impact on quality of work life, job retention, and self-esteem (13).

Failure to acknowledge the rights of people with disability was evident in forms of microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse rooted in systems and structures. The articles discussed organisational structures that did not start from a rights-based perspective or support participation and agency of people with disability (2, 5, 13, 15, 25, 27, 28). These systems caused harm by failing to provide the services needed for people to exercise their rights (17). Fraser-Barbour et al. (Citation2018, p. 9) noted that some mainstream service providers did not “actively plan and engage with people with intellectual disability” who had experienced abuse. Organisational forms of microaggressions included “proofing practices” that required young people in wheelchairs to re-prove their need for support and access to transport (Calder-Dawe et al., Citation2020, p. 149); treating people with cognitive disability as second-class citizens, through formal and informal policies that segregated and restricted access to opportunities available to others (11, 26); and inadequate financial support of state-funded services (28), which in one case led to the deaths of nine people with disability (1). Moral et al. (Citation2022) argued that inadequate financial resourcing and inaccessibility to public spaces, recreational and cultural activities, and transport amounted to misrecognition of people with disability who were prevented from participating in everyday activities.

Ableism, stereotyping and stigma

The last theme concerned the ableism behind everyday harm. Articles described personal, organisational and systems-based attitudes around ableism, stereotyping and stigma that established an environment where everyday harm and misrecognition were more likely to occur. Ableism and negative social attitudes and structures were noted in most articles. Ableism valued some abilities over others, underpinned experiences of harm and was an “insidious part of culture” (Kattari, Citation2020, p. 485). Combined with discrimination, ableism caused harm (23) and ableist structures even facilitated harm within organisations (35).

A related concept of “everyday ableism” is theorised in the literature and referred to mundane enactments of ableist prejudice and privilege across life domains. This reflected “broader sociocultural relations of power, while also being a profoundly personal, relational and embodied experience” (Schroer & Bain, Citation2020, p. 134). Everyday ableism activated harm that was misinformed, blatant, and latent (32), subtle, overt, and covert (12); and was both interpersonal and organisational (1, 3, 35). A key tenet of ableism was visibility of the body, which was surveyed, observed, policed and judged in public spaces, workplaces, schools, and at home (5, 24, 33). This viewing of the body led to unsolicited comments and opinions and to “unwanted sympathy and cures” (Calder-Dawe et al., Citation2020, p. 133). Challenging, patronising or critiquing a person’s identity and body were examples of microaggression that constituted denial of personhood. By contrast, harm to people with invisible disability was experienced when they were visibly judged as not disabled enough (20). Where their visual presentation did not align with viewers’ expectations or stereotypes, people with disability were pulled into a form of “interactional trouble” with ableist responses to their abilities that failed to acknowledge or value them (2).

Feeling valued in everyday life was undermined by experiencing stereotyping and stigma and was felt in abuse and exclusion. The types of stigma identified as microaggression or emotional and psychological abuse included labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss and discrimination in the context of power relations (3, 25, 30, 35). Stigma, the negative attitudes, and beliefs about people with disability, underpinned barriers to participation, rights, and access. Stigma was a barrier to accessing health services (18) and prevented para-athletes from accessing support to compete or participate (30). People were stigmatised despite public education around stereotypes and disability (5, 9, 32).

The reviewed literature demonstrated how harm occurred at an interpersonal and organisational level, underpinned by a lack of recognition, care, respect, and esteem. All abuse involves misrecognition, evident in microaggressive acts, in emotional and psychological abuse and in more explicit forms of violence. The literature emphasised people with disability’s perspective about the subtle, chronic, and accumulating nature of harm (2, 5, 27, 34).

Discussion

The purpose of the scoping review was to understand the evidence about microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse of people with disability, and how this could contribute to an understanding of the new term “everyday harm” of people with disability. Better understanding subtle and pervasive forms of harm can contribute to improving the ways that people identify acts that damage relationships, including paid support relationships. By helping people to notice and name slippery concepts, they can start to think about how to prevent and respond to everyday harm.

The review demonstrated a close connection between the concepts of microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse, which is consistent with our preliminary framing of everyday harm (Robinson et al., Citation2022). Together, the concepts identified actions and omissions that were sometimes subtle harm, and were often not clearly understood or adequately responded to. This harm had overlapping consequences where people with disability were overlooked, disrespected, and disregarded in interpersonal and organisational encounters. Valuable concepts in the review were unequal power relationships within which harm occurs, ambiguous intent, cumulative harm, and acknowledgement and understandings of actions and omissions causing everyday harm. Understanding more about the effect of repeated experiences of microaggressions or misrecognition, and how to counter the impacts is an important avenue for further research.

The concept of everyday harm may offer a contribution through reframing microaggression about groups who are likely to find the broader theory inaccessible. It could provide an accessible language for daily use. Informed by recognition theory, our concept of everyday harm focuses on interpersonal harm and how it affects the quality of the relationship. This stretches microaggression theory beyond identifying and evaluating the effect of delivered and received negative exchanges toward someone based on social group membership (Conover et al., Citation2017). The everyday harm concept and language could create opportunities for exploring possibilities for restoration and prevention of further harm in the relationship.

The literature about microaggression was about actions or omissions based on social group membership and the cumulative effect of these deeds (Sue, Citation2010). The concepts pointed to microaggression and emotional and psychological abuse evident through ableism, stereotyping, stigma, and group identity. Using recognition theory to frame everyday harm could illuminate how to address misrecognition directed at a person based on group membership (cognitively disabled) as well as a person within a type of relationship (paid support).

At an organisational level, formal and informal rules affect how paid interpersonal relationships are enacted/conducted. The review showed that power relationships and structures contributed to harm. These structures included formal rules or facilities (Lett et al., Citation2020); or informal norms of discrimination in interpersonal working relationships and organisational cultures (Ellem et al., Citation2020; Rutland et al., Citation2022). Applying recognition theory could illustrate the organisational norms that shape culture and practice at the interpersonal relationship level, where people experience everyday harm (Robinson et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion

This review has drawn together research about subtle, common harm in the lives of people with disability, which is often poorly identified and responded to. A striking feature of the literature is that sometimes the people who experience this harm fall from view as the analytical gaze turns to the action, intention, or attitude of the person or institution committing the microaggression. For people with cognitive disability, whose agency is often compromised (Gjermestad et al., Citation2017), this flags a need to redirect attention towards the felt and expressed experience of everyday harm.

The findings raise questions as we further develop the concept of everyday harm in relationships in organisational contexts (Ikäheimo, Citation2022; Smyth et al., Citation2023). Noted by Keller and Galgay (Citation2010) and Schroer and Bain (Citation2020), more evidence is needed about how people with cognitive disability respond to harm and how people close to them perceive and act on it. Addressing these gaps in evidence could identify factors needed to change culture in disability support and to shift power towards the people receiving services so they can influence the quality of their relationships with support workers.

Misrecognition, the inverse of recognition, opens the opportunity for analytical exploration of how people feel uncared for, disrespected, and devalued in their paid support relationships and organisational contexts – and what can be done to address this. Research about how people in working relationships understand these kinds of behaviours can inform ways to improve the quality of their work together.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our Flinders University team members Rachel High, Ruby Nankivell, and Raffaella Cresciani and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful insights on the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We use the term “cognitive disability” to describe people with intellectual disability and neurodiverse people. Our mixed research team confirmed the preference for language with self-advocates, research participants, and the four community researchers in our team who are themselves people with cognitive disability.

References

- Araten-Bergman, T., & Bigby, C. (2023). Violence prevention strategies for people with intellectual disabilities: A scoping review. Australian Social Work, 76(1), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2020.1777315

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Broome, R. (2020). “They had little chance”: The kew cottages fire of 1996. Victorian Historical Journal, 91(2), 245–266.

- Calder-Dawe, O., Witten, K., & Carroll, P. (2020). Being the body in question: Young people’s accounts of everyday ableism, visibility and disability. Disability & Society, 35(1), 132–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1621742

- Canel-Çinarbaş, D., Kaymak, D. A., & Sart, Z. H. (2022). Disability and discrimination: Microaggression experiences of people with disabilities in Turkey. In Hüseyin Çakal & Shenel Husnu (Eds.), Examining complex intergroup relations: Through the lens of Turkey (pp. 47–66). Routledge.

- Coalson, G. A., Crawford, A., Treleaven, S. B., Byrd, C. T., Davis, L., Dang, L., Edgerly, J., & Turk, A. (2022). Microaggression and the adult stuttering experience. Journal of Communication Disorders, 95, Article 106180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2021.106180

- Conover, K. J., Acosta, V. M., & Bokoch, R. (2021). Perceptions of ableist microaggressions among target and nontarget groups. Rehabilitation Psychology, 66(4).

- Conover, K. J., & Israel, T. (2019). Microaggressions and social support among sexual minorities with physical disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000250

- Conover, K. J., Israel, T., & Nylund-Gibson, K. (2017). Development and validation of the Ableist Microaggressions Scale. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(4), 570–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017715317

- Corrigan, P. W., Shah, B. B., Lara, J. L., Mitchell, K. T., Combs-Way, P., Simmes, D., & Jones, K. L. (2019). Stakeholder perspectives on the stigma of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Addiction Research & Theory, 27(2), 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1478413

- Cortis, N., & Van Toorn, G. (2022). Safeguarding in Australia's new disability markets: Frontline workers’ perspectives. Critical Social Policy, 42(2), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183211020693

- Eisenman, L. T., Rolon-Dow, R., Freedman, B., Davison, A., & Yates, N. (2020). “Disabled or not, people just want to feel welcome”: Stories of belonging from college students with intellectual disability. Critical Education, 11(17), 1–21.

- Ellem, K., Smith, L., Baidawi, S., McGhee, A., & Dowse, L. (2020). Transcending the professional–client divide: Supporting young people with complex support needs through transitions. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37(2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00651-x

- Eun-Jeong, L., Ditchman, N., Thomas, J., & Tsen, J. (2019). Microaggressions experienced by people with multiple sclerosis in the workplace: An exploratory study using Sue's taxonomy. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000269

- Ezer, T., Wright, M. S., & Fins, J. J. (2020). The neglect of persons with severe brain injury in the United States: An international human rights analysis. Health & Human Rights: An International Journal, 22(1), 265–278. http://ezproxy.flinders.edu.au/login?url = https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct = true&db = cin20&AN = 144318990&site = ehost-live

- Fraser-Barbour, E. F., Crocker, R., & Walker, R. (2018). Barriers and facilitators in supporting people with intellectual disability to report sexual violence: Perspectives of Australian disability and mainstream support providers. The Journal of Adult Protection, 20(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAP-08-2017-0031

- Friedman, C. (2021). The impact of ongoing staff development on the health and safety of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 33(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-020-09743-z

- Fyson, R., & Patterson, A. (2020). Staff understandings of abuse and poor practice in residential settings for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(3), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12677

- Gjermestad, A., Luteberget, L., Midjo, T., & Witsø, A. E. (2017). Everyday life of persons with intellectual disability living in residential settings: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Disability & Society, 32(2), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1284649

- Hayashi, M. (2022). Child psychological/emotional abuse and neglect: A definitional conceptual framework. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 15(4), 999–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-022-00448-3

- Honneth, A. (1995). The struggle for recognition: The moral grammar of social conflicts. Polity Press.

- Honneth, A. (2004). Recognition and justice: Outline of a plural theory of justice. Acta sociologica, 47(4), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699304048668

- Ikäheimo, H. (2022). Recognition and the human life-form: Beyond identity and difference. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003272120

- Kattari, S. K. (2020). Ableist microaggressions and the mental health of disabled adults. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(6), 1170–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00615-6

- Kattari, S. K., Ingarfield, L., Hanna, M., McQueen, J., & Ross, K. (2020). Uncovering issues of ableism in social work education: A disability needs assessment. Social work education, 39(5), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1699526

- Kattari, S. K., Olzman, M., & Hanna, M. D. (2018). You look fine!: Ableist experiences by people with invisible disabilities. Affilia, 33(4), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109918778073

- Keller, R. M., & Galgay, C. E. (2010). Microaggressive experiences of people with disabilities. In D. W. Sue (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact (1. Aufl. Ed.) (pp. 241–267). Wiley.

- Lett, K., Tamaian, A., & Klest, B. (2020). Impact of ableist microaggressions on university students with self-identified disabilities. Disability & Society, 35(9), 1441–1456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1680344

- Lourens, H. (2021). Giving voice to my body: Healing through narrating the disabled self. Disability & Society, 36(6), 849–863. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1778445

- Matin, B. K., Williamson, H. J., Karyani, A. K., Rezaei, S., Soofi, M., & Soltani, S. (2021). Barriers in access to healthcare for women with disabilities: A systematic review in qualitative studies. BMC Women's Health, 21(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01189-5

- Miller, A. L., & Kurth, J. A. (2022). Photovoice research with disabled girls of color: Exposing how schools (re)produce inequities through school geographies and learning tools. Disability & Society, 37(8), 1362–1390. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1881883

- Miller, R. A., & Smith, A. C. (2021). Microaggressions experienced by LGBTQ students with disabilities. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 58(5), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2020.1835669

- Moral, E., Huete, A., & Díez, E. (2022). #Mecripple: Ableism, microaggressions, and counterspaces on twitter in Spain. Disability & Society, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2161348

- Morrison, E. H., Sorkin, D., Mosqueda, L., & Ayutyanont, N. (2020). Abuse and neglect of people with multiple sclerosis: A survey with the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS). Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 46, Article 102530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2020.102530

- O'Hagan, K. P. (1995). Emotional and psychological abuse: Problems of definition. Child Abuse & Neglect, 19(4), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(95)00006-T

- Owen, J., Tao, K. W., & Drinane, J. M. (2019). Microaggressions: Clinical impact and psychological harm. In G. C. Torino, D. P. Rivera, C. M. Capodilupo, K. L. Nadal, & D. W. Sue (Eds.), Microaggression theory: Influence and implications (pp. 65–85). Wiley.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, Article n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Porter, T., Shakespeare, T., & Stockl, A. (2022). Trouble in direct payment personal assistance relationships. Work, Employment and Society, 36(4), 630–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211016972

- Robinson, S., & Chenoweth, L. (2012). Understanding emotional and psychological harm of people with intellectual disability: An evolving framework. The Journal of Adult Protection, 14(3), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/14668201211236313

- Robinson, S., Fisher, K. R., Graham, A., Ikäheimo, H., Johnson, K., & Rozengarten, T. (2022). Recasting ‘harm’ in support: Misrecognition between people with intellectual disability and paid workers. Disability & Society, 38(9), 1667–1688. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2029357

- Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. (2023). Final report: Executive summary. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Rutland, E. A., Suttiratana, S. C., da Silva Vieira, S., Janarthanan, R., Amick, M., & Tuakli-Wosornu, Y. A. (2022). Para athletes’ perceptions of abuse: A qualitative study across three lower resourced countries. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 56(10), 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104545

- Schroer, J. W., & Bain, Z. (2020). The message in the microaggression: Epistemic oppression at the intersection of disability and race. In L. Freeman, & J. W. Schroer (Eds.), Microaggressions and philosophy (pp. 226–250). Routledge.

- Smyth, C., Fisher, K. R., Robinson, S., Ikäheimo, H., Hrenchir, N., Idle, J., & Yoon, J. (2023). Policy representation of everyday harm experienced by people with disability. Social Policy & Administration, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12985

- Sue, D. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sue, D., Capodilupo, C., & Holder, A. (2008). Racial microaggressions in the life experience of black Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(3), 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.329

- Sullivan, J. (2021). ‘Pioneers of professional frontiers’: The experiences of autistic students and professional work based learning. Disability & Society, 38(7), 1209–1230. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1983414

- Thorneycroft, R. (2020). Walking to the train station with Amal: Dis/ability and in/visibility. Disability & Society, 35(6), 861–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1650720

- Torino, G. C., Rivera, D. P., Capodilupo, C. M., Nadal, K. L., & Sue, D. W. (2019). Everything you wanted to know about microaggressions but didn't get a chance to ask. In G. C. Torino, D. P. Rivera, C. M. Capodilupo, K. L. Nadal, & D. W. Sue (Eds.), Microaggression theory: Influence and implications (pp. 3–15). Wiley.

- Wayland, S., Newland, J., Gill-Atkinson, L., Vaughan, C., Emerson, E., & Llewellyn, G. (2022). I had every right to be there: Discriminatory acts towards young people with disabilities on public transport. Disability & Society, 37(2), 296–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1822784

- Willis, D. (2020). Whorlton Hall, Winterbourne View and Ely Hospital: Learning from failures of care. Learning Disability Practice, 23(6), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.7748/ldp.2020.e2049

- Wiseman, P., & Watson, N. (2022). “Because i've got a learning disability, they don't take me seriously:” Violence, wellbeing, and devaluing people with learning disabilities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13/14), NP10912–NP10937. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521990828

- Women With Disabilities Australia (WWDA). (2007). Forgotten sisters – A global review of violence against women with disabilities. WWDA Resource Manual on Violence Against Women With Disabilities. Tasmania, Australia: WWDA.