Abstract

Objective. To determine (a) the relationship between life satisfaction, anxiety, depression and ageing in the male community and (b) to identify the impact of vulnerability factors, personal and social resources on life satisfaction and distress.

Design. A stratified random sample of the German male population (N = 2144) was investigated by standardized questionnaires of life satisfaction (FLZM), depression, anxiety (PHQ), resilience (RS-11) and self-esteem (RSS).

Results. No age-related change was found regarding overall life satisfaction. Satisfaction with health decreased in midlife (51–60 years), while the importance of health increased. Importance of and satisfaction with partnership and sexuality were only reduced in the oldest group (70+). Anxiety was highest around midlife (51–60 years), accompanied by reduced resilience and self-esteem. No clear age-related change was found regarding depression. Life satisfaction was strongly associated with resilience, lack of unemployment, the presence of a partnership, positive self-esteem, a good household income, the absence of anxiety and depression and living in the Eastern states.

Conclusions. Personal and social resources and the absence of anxiety and depression are of crucial importance for the maintenance of life satisfaction in ageing men. There is also evidence for a crisis around midlife manifested by health concerns, anxiety and reduced resilience.

Introduction

Industrialized societies are characterized by an ageing population. The health of ageing men has found much less attention than the health of postmenopausal women [Citation1]. Recently, age-associated complaints of men have been discussed under the headline of a (Partial) Androgen Deficiency in the Ageing Male (‘(P)ADAM’), including diminished sexual desire, erectile quality, intellectual activity, and increases of fatigue, depressed mood and irritability [Citation2]. Yet, it remains an issue of debate, if these symptoms and complaints are specific enough to define a clinical syndrome like female menopause [Citation3]. As we could show in a recent representative survey, a broad array of physical (e.g. cardiovascular, musculosceletal) complaints increased steadily with age in the general male population, accompanied by fatigue, exhaustion, depression and a reduction of activity, motivation and health satisfaction [Citation4]. The level of testosterone and its trajectory across life vary widely among individuals [Citation5], and the relationships between the symptoms and the level of testosterone are weak [Citation6]. Besides hormonal changes, age-related somatic comorbidity, adverse health behaviour, mental comorbidity (anxiety, depression), social factors (unemployment, lack of social integration [Citation7]) and low education [Citation8] constitute additional vulnerability factors for the health of ageing men [Citation9].

Traditionally, ageing has been regarded as a process of inevitable decline of health, capabilities and engagement. From the perspective of active ageing, a deficit-oriented view was eschewed as an impediment to a productive and healthy process of ageing. In order to explain the widespread observation that some individuals have a good psychological outcome despite suffering from life events and strains expected to cause ongoing suffering and distress, the term resilience was coined. It implies a capacity to resist to stressful experience and to maintain health and psychosocial functioning despite adverse circumstances. In the ageing population, adaptation to and balancing cumulating losses has increasingly been viewed as a function of resilience [Citation10] and other personal (e.g. self-esteem) and social (e.g. partnership, income, employment, education) resources [Citation4,Citation8].

Life satisfaction is a multifaceted concept covering domains such as friendships, leisure time activities/hobbies, general health, income, housing/living conditions, family life and partnership/sexuality. This study determines life satisfaction, distress and resilience of men in the general population across the life span. We do not only take the satisfaction with specific life domains into account, but also their respective importance. Based on a representative community sample across the life span of adult men, this study addresses the following issues:

Is there an overall decrease of life satisfaction across cohorts of different age groups?

How do the significance and satisfaction with specific domains of life satisfaction change with age?

How do depression and anxiety evolve across cohorts of different age groups?

What is the impact of vulnerability (e.g. previous unemployment) and protective (esp. resilience) factors on the life satisfaction of ageing men?

We assume that (a) life satisfaction is not associated with age in a linear manner, but rather that importance and satisfaction with different domains change across different age cohorts; (b) the relation of life satisfaction to ageing depends on protective and vulnerability factors; (c) resilience is a significant protective factor.

Methods

Study participants

This study is based on a representative survey of the German population recruiting a total of 2144 men between the ages of 18 and 92 years by June 2006. Data were collected by a demographic consulting company (USUMA) based on 258 sample-points in Eastern and Western parts of Germany. Participants were questioned by trained interviewers in their homes (face-to-face interviews). Households were selected by the random-route-procedure; the target person in each household was also selected randomly. The sample was representative for the total German male population (as confirmed by ADM – samples [Citation11]). Of the initial sample 62.1% could be contacted; this is well in the range of quotas of other representative community samples [Citation12].

The mean age of the sample was 50.1 years (). For further analyses the sample was divided into six age groups with comparable proportions: 18–30 years: N = 346, 31–40 years: N = 328, 41–50 years: N = 398, 51–60 years: N = 380, 61–70 years: N = 442, and over 70 years: N = 250. About 60% of the men were married, and almost two third lived in a partnership. The great majority (over 80%) had less than high school education, and household income was mostly (76%) less than €2,500 per month. Seventy-two percent reported a religious affiliation. About 52% were employed, 35% were on pension, 7% were unemployed, and 6% reported schooling. The majority (79%) lived in the Western states of Germany; 86.5% lived in urban areas (cities >20,000 inhabitants).

Table I. Study participants (N = 2144).

Questionnaires

In addition to sociodemographic questions, psychological variables were assessed by validated and standardized self-report inventories. The Questions on Life Satisfaction FLZM is a multi-dimensional self-report measure of general life satisfaction and satisfaction with health [Citation13]. The general domains cover friends, leisure time activities/hobbies, general health, income, school, housing/living conditions, family life and partnership/sexuality. Respondents weigh their satisfaction with each of the eight domains of daily life in relation to the subjective importance of the domain. In the first step, respondents rate the subjective importance of each dimension on a scale from 1 (‘not important’) to 5 (‘extremely important’). Then they rate the present satisfaction with these dimensions on a scale from ‘1 = dissatisfied’ to ‘5 = very satisfied’. The weighted scores are calculated by the formula weighted satisfaction = (importance rating − 1) × (2 × satisfaction rating) − 5. Negative scores indicate dissatisfaction, whereas positive scores indicate satisfaction, and zero indicates no subjective importance of the specific domain for the individual's life satisfaction. Sufficient internal consistency scores for the life satisfaction sum-scores are indicated by Cronbach's α of 0.70 for general life satisfaction and 0.75 for health-related satisfaction.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) was assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale GAD-7, a reliable and valid self-report instrument which was standardized in a national face-to-face household survey with a representative sample of 5030 subjects. A score of 10 and more was found in 5% of the participants; this score was associated with a high likelihood ratio of 5.5 for the presence of any anxiety disorder [Citation14].

Depression was measured with the two item depression screener of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2). For the detection of major depressive disorder a cut-off of 3 yielded a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 78%. For any depressive disorder, sensitivity was 79% and specificity 86%. The scale also appeared valid for grading depression severity and monitoring outcome [Citation15–17].

Resilience was defined as the ability to use internal and external resources successfully in order to adapt to developmental tasks. It was measured by the 11-item short form of the resilience scale by Wagnild and Young [Citation18] which was validated by Leppert et al. [Citation10] based on a sample of 594 elderly men and women. The original version distinguished the dimensions of personal competence covering characteristics such as self-reliance, independence, mastery and endurance (e.g. ‘When I have plans, I follow them through’). Acceptance of the self and life was characterized by adaptability, tolerance and flexible perspectives (e.g. ‘I take things as they come’). In addition, a total score can be computed. As the proposed factor structure of the scale could not be reproduced in the German population, a short form was developed with comparable reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.90 vs. 0.94) and high correlations with the long version (r = 0.95; p < 0.001).

Self-esteem was measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSS). This scale is a 10-item self-report measure of global self-esteem with good reliability and validity across a large number of different sample groups. It consists of 10 statements related to overall feelings of self-worth or self-acceptance. The items are answered on a four-point scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ [Citation19].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done by SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) for Windows (version 15.0) by parametric procedures (One way ANOVA with Scheffé tests for post hoc comparisons). Multiple regressions were performed with stepwise entry of the predictors age, Western/Eastern states, rural/urban residence, presence of a partnership, previous experience of unemployment, household income and religious affiliation; dependent variables were life satisfaction (general, importance of and satisfaction with specific domains), anxiety, depression, resilience and self-esteem.

We defined the level of significance at p < 0.001; we additionally report effects with lower levels of confidence (p < 0.01; p < 0.05). Because of the exploratory character of this study we did not perform alpha-adjustment.

Results

General life satisfaction

Neither the analysis of variance (p < 0.001) nor Scheffé tests (p < 0.05) yielded a significant effect across cohorts (means: 18–30 years: 3.73; 31–40 years: 3.83; 41–50 years: 3.74; 51–60 years: 3.69; 61–70 years: 3.75; >70 years: 3.65). Thus, there was no evidence of a reduced general life satisfaction in the course of ageing.

As detailed analyses of the domains of life satisfaction show, the importance and the satisfaction in the individual domains, however, changed with increasing age.

Importance and satisfaction with specific domains of life satisfaction

lists domains according to decreasing importance and satisfaction: Overall, health was rated as most important (mean 4.51), followed by income (4.17), family (3.93), living conditions (3.90), partnership and sexuality (3.85), work (3.84), friends (3.67) and leisure time (3.52).

Table II. Importance of and satisfaction with domains of life satisfaction across the life span (N = 2144 men).

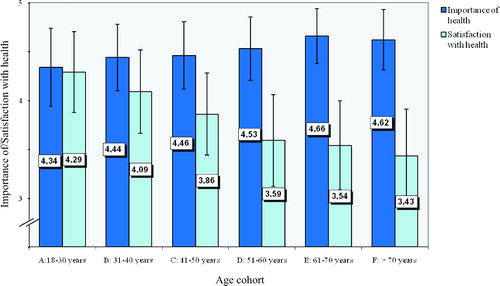

depicts importance of and satisfaction with health across the age cohorts. As shows, the importance of health increased in the 50s and beyond (compared to young men). Satisfaction with health, however, began to decline in the forties; further decline was reported in the 50s.

Figure 1. Importance of and satisfaction with health for German men in different age cohorts (N = 2144). Presented are means and SDs. ANOVA (Scheffé-tests with p < 0.05 in parentheses for the six age groups). (1) Importance F(5/2134) = 11.44; p < 0.001 (D,E,F > A; E > A,B,C); (2) Satisfaction F(5/2134) = 48.93; p < 0.001 (A,B > C > D,E,F).

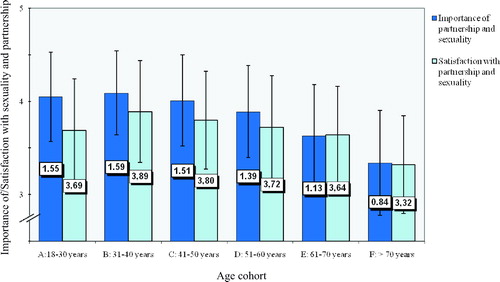

The importance of sexuality and partnership and the satisfaction with this domain are illustrated in . Both were significantly reduced in the oldest group >70 years (compared to all other age groups).

Figure 2. Importance of and satisfaction with partnership and sexuality for German men in different age cohorts (N = 2144). Presented are means and SDs. ANOVA (Scheffé tests with p < 0.05 in parentheses for the six age groups): (1) Importance F(5/2134) = 25.47 (A,B,C,D,E > F); (2) Satisfaction F(5/2127) = 9.18; p < 0.001 (A,B,C,D,E > F).

With increasing age, the importance of the following domains decreased: Income was considered least important by the oldest age group (compared to the age group from 31 to 50 years). There was a gradual decline of the importance of friends (starting from early adulthood (31–40 years) and work (>61 years). The importance of leisure time activities was reduced in the 40s and 50s and beyond compared to young men. Family life and children gained importance in the 30s and remained important throughout old age.

The order of domains was different regarding satisfaction: Overall, satisfaction with living conditions was highest (3.97), followed by friends (3.88), family life/children (3.87), health (3.80), leisure time (3.77), partnership/sexuality (3.70), work (3.46), and income (3.41) was least. Satisfaction with living conditions was increased from the 50s throughout old age (compared to young men), and satisfaction with family life and children was increased in the 30s and maintained throughout old age. Regarding income, satisfaction was low in the youngest group (18–30 years) and also around midlife (51–60 years), while satisfaction was increased in old age. Satisfaction with friends was only reduced in the 70s.

Anxiety and depression

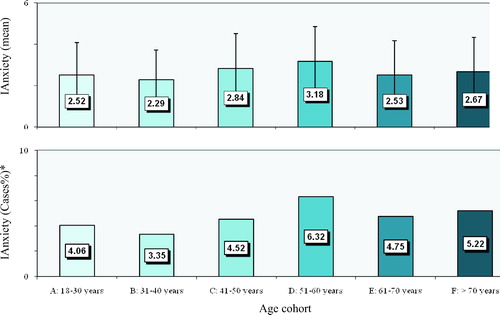

shows anxiety across the life span. There was an increase of anxiety in midlife (51–60 years; proportion of cases 6.3%) compared to younger adults (31–40 years; cases 3.4%; p < 0.01).

Figure 3. Anxiety of German men in different age cohorts (N = 2144). Presented are means, SDs (top) and proportions of cases (bottom). ANOVA (Scheffé-tests with p < 0.05 in parentheses for the six age groups). F(5/2136) = 3.31; p < 0.01 (D > B). *Cut-off: anxiety ≥10.

As shows, mean depression scores and the proportions of participants above the cut-off score (‘cases’) did not differ.

Table III. Depression, resilience and self-esteem across the life span (N = 2144 men).

Resilience and self-esteem

As shows, there was a significant reduction of resilience at the age of 51–60 years and, most pronounced, in the 70s. This was accompanied by a reduction of self-esteem in midlife (51–60 years) vs. adulthood (31–40 years).

Resilience showed significant positive correlations with general life satisfaction (r = 0.41), self-esteem (r = 0.59), and negative correlations with depression (r = −0.35) and anxiety (r = −0.30). Similar correlations were found for self-esteem with general life satisfaction (r = 0.43), depression (r = −0.50) and anxiety (r = −0.45).

Predictors of life satisfaction

shows the determinants of general life satisfaction, distress (depression, anxiety) and resilience. General life satisfaction was statistically predicted in declining order by resilience, previous unemployment, the presence of a partnership, higher self-esteem, household income, the absence of generalized anxiety disorder and depression, and living in the Eastern states. When all variables were taken into account, age added little to the overall statistical prediction. A substantial proportion of 38% of the variance was explained. Religious affiliation, rural or urban residence made no difference.

Table IV. Determinants of general life satisfaction, depression, anxiety and resilience.

Predictors of anxiety, depression and resilience

Previous unemployment, residence in East Germany, low degrees of resilience, self-esteem and low household income were statistical predictors of depression, explaining 27% of variance. Similarly, low degrees of self-esteem, previous unemployment, low household income and lack of religious affiliation were associated with anxiety (22% of variance explained).

Prediction of resilience was less successful (only 9% of variance explained). Lower age, a higher household income, lack of previous unemployment residence in East Germany, presence of a partnership, Eastern and urban residence were associated with higher resilience.

Discussion

This study has the virtue of being based on a large and representative community sample of men covering the entire age range. Limitations refer to the fact that cohorts of men do not simply represent life trajectories, but also different historical effects. Although a response rate of 62% is well in the expected range, we cannot exclude bias. Also, the assessment of distress was limited to self-report instruments, which, however, were of proven reliability and validity. In this community survey, we could not include biological measures (e.g. hormones). Even though we found strong associations between life satisfaction and vulnerability and protective factors, their causal relationship must be interpreted with caution, i.e. while it is plausible that unemployment contributes to depression, an episode of depression may also precede the loss of a job. Overall, the importance of health, income and family life were rated highest, whereas the satisfaction was highest for living conditions, friends and family life. There was no evidence of a reduction of general life satisfaction among elderly men. As detailed analyses showed, the importance and the satisfaction in the individual domains, however, changed with age, reflecting specific tasks and concerns in the life cycles of men.

Regarding the importance and the satisfaction of the eight domains in the six age cohorts,

The importance of health increased starting from midlife (51–60 years), whereas the satisfaction with health was decreased in men already in their 40s and further in their 50s.

Both, the importance of and the satisfaction with partnership and sexuality were well maintained throughout the 60s and declined only in the oldest group (70+).

Friends were rated as most important in the youngest group.

Family life gained increasing importance in the 30s as men married and fathered children, persisting throughout ageing.

Being highly important across cohorts, the importance of income was lowest in old age; satisfaction with income, however, was comparatively high among elderly vs. young men.

Satisfaction with living conditions increased starting from the 50s.

Importance of work declined around retirement age (61+ years)

Leisure time/hobbies were most important among young men; there was no clear age difference regarding satisfaction.

Interestingly, in the age cohort from 51 to 60 years anxiety peaked, and resilience and self-esteem were reduced. Taken together, these changes can be seen as evidence for a crisis occurring around midlife. This crisis may both indicate health-related changes (increase of importance of health, decline of satisfaction) as described under the heading of the ageing male [Citation20], or a psychosocial transition, a so-called ‘midlife-crisis’ signalling limitations in career development or choices (e.g. reduced satisfaction with income) [Citation4].

Although satisfaction with health, the overall most important domain, declined among ageing men, overall life satisfaction was well maintained. This is most likely due to the fact that satisfaction with other domains (e.g. income, family, living conditions) was comparatively high. Although satisfaction with partnership and sexuality declined significantly in the oldest group; its impact on life satisfaction is most likely offset by the fact that elderly men also rated this domain as less important. Yet, resilience also declined further in the 70s, while self-esteem was maintained. There was no significant increase of anxiety or depression among the elderly.

Life satisfaction in ageing men crucially depends on the balance of resources, especially resilience, but also a good household income, the presence of a partnership, high self-esteem and religious affiliation. Not only depression, but also anxiety was a vulnerability factor for low life satisfaction, along with previous unemployment. When personal and social resources and stresses were taken into account, the negative contribution of age became quite small. The major vulnerability (low household income, previous unemployment, residence) and protective factors (self-esteem, resilience) were associated with anxiety and depression; again, age had only a small contribution (regarding depression). Andrologists should, therefore, attend to vulnerability factors (depression, anxiety, and unemployment) which have a negative impact on life satisfaction and quality of life, especially around midlife. They should also consider personal (resilience, self-esteem) and social (partnership, income) resources that help men maintain a high level of life satisfaction when faced with the adversities of the ageing process.

Declaration of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beutel ME, Weidner K, Schwarz R, Brähler E. Age-related complaints in women and their determinants based on a representative community study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004;117:204–212.

- Morales A, Lunenfeld B. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males. Official recommendations of ASSAM. Aging Male 2002;5:74–86.

- Lee DM, O'Neill TW, Pye SR, Silman AJ, Finn JD, Pendleton N, Tajar A, Bartfai G, Casanueva F, Forti G, Giwercman A, Huhtaniemi IT, Kula K, Punab M, Boonen S, Vanderschueren D, Wu FC. EMAS study group. The European Male Aging Study (EMAS): design, methods and recruitment. Int J Androl 2008;32:11–24.

- Beutel ME, Wiltink J, Schwarz R, Weidner W, Brähler E. Complaints of the ageing male based on a representative community study. Eur Urol 2002;41:85–93.

- Feldman HA, Longcope C, Derby CA, Johannes CB, Araujo AB, Coviello AD, Bremner WJ, Mckinlay JB. Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:589–598.

- Beutel ME, Wiltink J, Hauck EW, Auch D, Behre HM, Brähler E, Weidner W. Correlations between hormones, physical, and affective parameters in aging urologic outpatients. Eur Urol 2005;47:749–755.

- Strine TW, Chapman DP, Balluz L, Mokdad AH. Health-related quality of life and health behaviors by social and emotional support. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2008;43:151–159.

- Jankowska EA, Szklarska A, Lopuszanska M, Medras M. Age and social gradients in the intensity of aging males’ symptoms in Poland. Aging Male 2008;11:83–88.

- Blanker MH, Driessen LF, Bosch JLH, Bohnen AM, Thomas S, Prins A, Bernsen RM, Groeneveld FP. Health status and its correlates among Dutch community-dwelling older men with and without lower urogenital tract dysfunction. Eur Urol 2002;41:602–607.

- Leppert K, Gunzelmann T, Schumacher J, Strauss B, Brähler E. Resilienz als protektives Persönlichkeitsmerkmal im Alter. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2005;55:365–369.

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft ADM-Stichproben, Wendt B. Das ADM Stichprobensystem Stand 1993. In: Gabler S, Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik JHP, Krebs D, editors. Gewichtung in der Umfragepraxis. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag; 1994. pp 188–202.

- Koch A. ADM-Design und Einwohnermelderegister-Stichprobe. Stichproben bei mündlichen Bevölkerungsumfragen. In: Stichproben in der Umfragepraxis. Gabler S, Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik JHP, Krebs D, editors. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag; 1997. pp 99–116.

- Heinrich G, Herschbach P. Questions on Life Satisfaction (FLZM) – a short questionnaire for assessing subjective quality of life. Eur J Soc Psychol 2000;16:150–159.

- Löwe B, Gräfe K, Zipfel S, Spitzer RL, Hermann-Lingen C, Witte S, Herzog W. Detecting panic disorder in medical and psychosomatic outpatients: comparative validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire, a screening question, and physician's diagnosis. J Psychosom Res 2003;55:515–519.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan, PO, Loewe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:317–325.

- Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 2008;46:266–274.

- Löwe B, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnnaire (PHQ-2). J Psychosom Res 2005;58:163–171.

- Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Manag 1993;1:165–178.

- Schumacher J, Leppert K, Gunzelmann T, Strauss B, Brähler E. Die Resilienzskala – Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der psychischen Widerstandsfähigkeit als Personenmerkmal. Z klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother 2005;53:16–39.

- Vermeulen A. Andropause. Maturitas 2000;34:5–15.