Abstract

Objective. The primary aim was to evaluate the effect on blood pressure (BP) levels of a previously developed pedagogically structured BP card introduced to patients with inadequately controlled hypertension in primary care. The evaluation was based on the results of a pilot study which is briefly presented. The aim of the study was to validate the positive results from a pilot study in a different, larger setting, for a longer time, and to study the effects of a nurse-led individual health counseling strategy. Design. A “BP card” that summarized the essential targets of hypertension treatment was presented to patients with a small set of questions. An open, randomized, controlled study was performed testing the effect of the BP card: BP card with an added semi-structured nurse counseling versus usual care (3 groups) during 12 months. Results. The effects on BP levels differed greatly from results seen in the pilot study where BP fell significantly in the intervention group as compared with that in the control group. In the main study, however, BP levels declined more than 25/8.5 mmHg in all three groups, with no significant differences between the groups. Conclusion. The positive results in the pilot study could not be confirmed in the main study. Furthermore, the nurse-led individual health counseling strategy did not show any additive effects. The reasons for these discrepant findings may be external such as increased awareness of hypertension, and internal factors such as contamination and non-biased recruitment.

| Abbreviations | ||

| C | = | Controls |

| I | = | intervention group |

| IN | = | intervention with added nurse counseling group |

Introduction

Hypertension is a major independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Proper treatment of blood pressure (BP) in patients with hypertension leads to a reduced risk of stroke, ischemic heart disease, chronic heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases (Citation1). Recommendations on BP levels today suggest values lower than 140/90 mmHg in general and 140/85 mmHg for patients with diabetes (Citation1). About 30% of patients with treated hypertension reached target BP (TBP) according to repeated studies conducted in the 1990s (Citation2,Citation3). About 40% of the patients reached TBP in a Spanish study conducted in 2006 on hypertensive patients in primary care (Citation4), which is an improvement compared with a similar Spanish study conducted in 2002 (Citation5). Other studies also indicate that there is a trend toward a larger proportion of patients reaching TBP in both the US and Europe (Citation6). To increase therapeutic compliance and to achieve better BP control, different pedagogic interventions have been undertaken: telephone reminders (Citation7,Citation8), home BP measurement (Citation9), social support (Citation10), written messages (Citation11) and internet-based counseling (Citation12). However, no single method has been shown to be superior and it has been suggested that a combination of strategies may be more effective (Citation13). Systematic health counseling by a nurse has been studied in Finnish patients with hypertension (Citation14), with a systolic BP difference of − 2.6 mmHg in the intervention group with no antihypertensive treatment, and the difference persisted after 2 years. No difference in BP was seen in the control group receiving treatment as usual.

Research has shown that patients become more motivated if health care professionals support the patients’ own initiatives and wishes (Citation15,Citation16). Nurse-led patient education concerning secondary preventive measures has shown good results in the achievement of lifestyle changes and quality of life, as well as reduced mortality (Citation17). However, in a 10-year follow-up there was no significant difference in total mortality or coronary events (Citation18).

The primary aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect on BP levels of a pedagogically structured BP card introduced to patients with inadequately controlled hypertension in primary care. The aim of the study was to corroborate the positive results from a briefly presented earlier pilot study in a different, larger setting, over a longer period of time, and to study the possible additive effect of a nurse-led individual health counseling strategy.

Methods

Patients were included who were over 18 years of age, visiting their physician and found to have uncontrolled BP in relation to individual TBP and in need of a BP measurement within 6 weeks. Patients who were judged by their physician as not to be able to fulfill study protocol due to severe diseases, and patients who did not speak Swedish well enough to understand the written instructions were excluded from the study. Patients with newly diagnosed hypertension as well as those with uncontrolled longstanding hypertension, patients with diabetes, ischemic heart disease or other atherosclerotic manifestations were included. There were no restrictions in regard of number of antihypertensive drugs in relation to inclusion or exclusion of patients.

Patients with need of immediate antihypertensive treatment and follow-up were excluded.

Both the pilot study and the main study were randomized, open, parallel trials. Randomization was performed in blocks to ensure a balanced recruitment to the different study groups at each center.

After randomization to the respective intervention arms, the study protocol permitted the physician to choose one of three different TBP levels according to the patient's individual needs and in accordance with treatment recommendations in force at the time of the studies. At study start, information on the current BP was obtained with a calibrated sphygmomanometer by nurses and doctors at the primary health care center. Data on current drug use, BP-related health care visits during the time of the study, and final BP were retrieved from patient records and checked with the patient at the follow-up. A sphygmomanometer was used to make maximum attendance possible for the primary health care centers.

Interventions

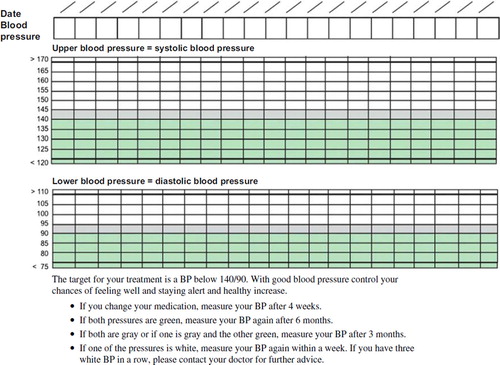

For patients in the intervention groups (I and IN), the BP card () was introduced to the patient after giving short verbal information on the reason for BP treatment, the aim of the treatment, different target levels, as well as the individual TBP. The patients’ knowledge and opinion regarding hypertension treatment was evaluated by the treating physician with the following questions:

“Do you know the reason for and the aim of your antihypertensive treatment? Do you know why it is important to treat hypertension?”

“Do you know how you can help yourself to improve your blood pressure?”

“How do you experience taking antihypertensive drugs every day, is it difficult to remember?”

The BP card contained information on TBP in numeric and graphic forms, see and . Patients were instructed to enter their current BP on the card (usually obtained from nurse visits) and to follow a set of simple rules of action in response to different BP levels. TBP was noted in a green field. If the BP was 5 mmHg above the desirable level it was noted in the gray area. If it was higher, it was noted in the white field, thus giving an immediate visual impression of the degree of BP control.

At study end, BP was checked in a standardized way with an automatic BP-OMRON 705C gauge monitor in the same arm as used at inclusion. Three measurements were done at the patients’ primary health care center by study monitors (MS and GRW) one after the other, and the mean value of the second and third BP measurements was calculated.

In a third group (IN) in the main study a supplemental pedagogic intervention by a nurse was added comprising further focus on the study messages. The nurse-led intervention was aimed at creating an individual plan with the intention of reaching TBP as well as focusing on evidence-based guidelines on lifestyle changes and supporting the modifications the patient wanted to work with. The nurses used an empowerment approach with individual consultations in keeping with the simple rules of the BP card, or in response to patient needs (Citation19). The nurses received special training within the area and were particularly interested in hypertension management, current treatment recommendations and how to use the empowerment technique. Written hypertension information from evidence-based sources was given to the patients, and the nurses made phone calls and when needed back-up visits to reinforce the study objectives during the course of the study.

A pilot study was performed during 2001–2002 using the same type of intervention with a BP card described fully below at two primary health care centers (PHCs) in Sweden, in Nyköping and Salem, south of Stockholm. The target BP levels used in the pilot study were < 140/90 mmHg, < 150/90 mmHg and < 160/90 mmHg based on then active recommendations and allowing for individual adjustment. A total of 16 physicians participated in the study. In the pilot study, 112 patients were included but two patients were excluded because they did not meet the criteria. Thus, 110 patients were included and randomized to either the intervention group (I, n = 56) or control group (C, n = 54), who were given treatment as usual. Four patients actively declined after inclusion and one was lost to follow-up. The pilot study lasted for 9 months. Base-line data and results of the pilot study are presented in .

Table I. Data of the pilot study.

The main study was performed during 2005–2007 based on results of the pilot study. All 32 PHCs in the southwest region of Stockholm were invited to take part in the study and nine of them opted to participate and were included. A total of 50 physicians and 15 nurses participated. In the study 166 patients were included and randomized to three different groups. Two of them corresponded to those of the pilot study (Controls, C, n = 50, Intervention, I n = 57). In a third group (Intervention with nurse counseling, IN, n = 59) nurse counseling was added to the BP card intervention. Reason for dropping out of the study was declining to participate (n = 12), death or severe disease (n = 4) or movement from the area (n = 2). Drop-out rates were 3, 6 and 9 in I, IN and C, respectively. The main study lasted for more than 12 months. Details about the patients in these groups are presented in , and there were no statistical differences between the groups within the study at study start.

Table II. Comparative data at inclusion in main study (intervention groups I and IN and controls).

In the study the treatment aims were < 130/80 (diabetes and kidney disease), < 140/90 (all others) and < 150/90 mmHg (patients who did not tolerate lower levels). The higher levels were allowed under the condition that lifestyle changes were monitored at the time of the study.

The studies (both pilot and main studies) were approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board.

Statistics

Sample sizes and statistical power

The extended study was designed to show a decrease in systolic BP of 7.5 mmHg with 80% power and α = 0.05 based on the results of the primary study. We thus aimed at enrolling 50 patients per group, which allowed for a loss of 15 patients per group.

In the pilot study the t-test was used for primary variables and Wilcoxon's test was used for secondary variables. The Chi-square test was used to compare proportions.

One-way ANOVA with Tukey's test for post hoc comparisons of pairs was used. The data on contacts with the primary health care center (nurse, physician and telephone calls) were analyzed with the Kruskal–Wallis test with multiple comparisons, as the data were not normally distributed.

Results

BPs changed significantly in comparisons of start and end values (). Idem to the pilot study, no significant differences could be detected in systolic or diastolic BPs between the groups in relation to the intervention ().

Table III. Primary effect variables. BP and BP differences before and after intervention and percentage reaching TBP in main study in intervention and control groups.

The proportions of patients achieving TBP levels differed markedly, both in intervention and in control groups. In control groups, 50% reached treatment objectives. After intervention with the BP card, the proportion reaching TBP was 58% in the intervention group (I). The nurse-led intervention group (IN) showed a significantly lower proportion achieving TBPs () compared with both the Intervention (I) and control (C) groups.

The amounts of antihypertensive drugs prescribed per patient were within the same ranges in all groups at study start, as well as the prescription changes observed over time (). The prescribed amount of antihypertensive drugs increased in all groups when data before and after intervention were compared and was significant in the control group (C) and in the nurse-led intervention group (IN) ().

Table IV. Drug prescription and treatment-related health care contacts during study period in control and intervention groups.

Treatment-related health care contacts with the nurse were 0.6 times more common in the group receiving nurse intervention (IN) than in the control group (C) (p < 0.01).

The mean time used by the doctors to explain the intervention was slightly more than 10 min, without significant differences between the intervention groups, although the nurse-intervention group tended to visit their doctors less.

Discussion

In a randomized study of a pedagogic intervention for better BP control in primary care, we found divergent results as compared with an earlier pilot study with similar design. Opposed to expectation from a pilot study where BP decreased compared with controls there was no difference due to mode of intervention compared with controls. However, BP was markedly lowered in all three groups regardless of intervention. The reasons for these different findings are interesting and highlight several factors which have to be taken into account when doing research on complicated pedagogic interventions in a clinical setting.

There are some possible explanations for our findings. First, a general shift in knowledge about the importance of BP control and views toward the need for setting individual TBPs has occurred in the medical community over the years. National and international guidelines have recently stressed the need to be more active, and the risks of hypertension have been discussed in public media, which may have affected patients, nurses and physicians. Indications of this phenomenon are illustrated in Spanish studies of antihypertensive control in primary care, which showed markedly improved BP levels among hypertensive patients between 2002 and 2006 (Citation4,Citation5). Other studies also indicate a general trend in recent years toward a larger proportion of hypertensive patients reaching TBP in both the US and Europe (Citation6). This general trend may thus have negated the effect of the intervention in our extended study as compared with that in the primary study.

Second, the two studies had small but differing setups. The pilot study was performed in two different PHCs and the main study in nine, and thus the number of participating nurses and physicians was higher in the main. As a result, it may have been more difficult to keep the study objectives clear and updated in the main study participants. Moreover, differences in methods of BP measurements at baseline and end of study may have contributed to our findings.

Third, the difference in the follow-up time between the studies may have interfered with study results. There is evidence that time may cause the effect of pedagogic interventions to fade (Citation18). A study aiming at improving compliance and lowering BP in Birmingham found that the observed early positive effect declined with time (Citation20). The same phenomenon was observed after a 10-year follow-up period of a nurse-led secondary lifestyle prevention study (Citation18).

Fourth, in the pilot study, all doctors in the 2 PHCs participated, which differed from the main study, which relied more on doctors’ interest in participating. The main study also included a larger number thus entering the possibility of a higher degree of individual variability.

Fifth, a phenomenon described in studies of pedagogic interventions is contamination, meaning that involved doctors or nurses may start to apply the methods of the intervention in the control group (Citation21). As the studies were open and not double blind, nurses and physicians may unknowingly have changed their therapeutic behavior and thus interfered with study outcomes. A randomization on the doctor as well as the patient level may have been necessary to control this factor (Citation22).

Sixth, patients in the IN group did not reach TBP to the same extent as those in the two other groups. In our study nurses worked to increase hypertension awareness and concordance as well as to change lifestyle. As the nurse intervention was semi-structured to allow for individualization it may have entered subjective bias into the IN arm of the study. A more well-defined intervention approach may have been able to show additive results (Citation23). The nurse intervention seemed to provide fewer contacts with the physicians in our study, probably due to more communication between the nurse and the physician rather than directly between the patient and the physician. The Euroaction nurse-led multidisciplinary family program, where patients and their relatives were enrolled, improved BP control to a greater extent compared with usual care (Citation24). Another difference between the present study and the Euroaction program, which may explain their success, was that nurses could change dosages of antihypertensive drugs (Citation24), as few individuals with diagnosed hypertension reach TBP without antihypertensive drugs (Citation25).

Finally, the overall changes in BP before and after the intervention seemed large in the study. When judging this finding, the inclusion criterion that BP levels were out of acceptable range must be kept in mind, as well as the technique at study start and at study end. This may naturally have led to the selection of patients who were experiencing periods of especially high pressures, thus allowing for a high potential of positive results. Although we based our sample size calculation on a pilot study performed in a very similar way, caution should be taken when judging the result of a small study like this due to the possibility of statistical chance-findings.

There were fairly few patients who were lost to follow-up or dropped out and we believe that they did not have a considerable effect on our findings.

Conclusion

The positive results in the pilot study could not be confirmed in the main study. Furthermore, the nurse-led individual health counseling strategy did not show any additive effects. Pedagogical intervention studies are difficult, complex, and many external and internal factors may affect the outcome. The importance of finding effective ways to improve the use of effective treatments and facilitate behavioral change must not be hampered by these difficulties.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

The contents of this paper have not been presented elsewhere. The study was supported by grants from Stockholm County Council and the South West Drug and Therapeutics Committée, Stockholm County Council.

References

- Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–536.

- Colhoun HM, Dong W, Poulter NR. Blood pressure screening, management and control in England: results from a health survey for England 1994. J Hypertens. 1998;16: 747–52.

- Smith WC, Lee AJ, Crombie IK, Tunstall-Pedeo H. Control of blodd pressure in Scotland: the rules of halves. BMJ. 1990;300:981–3.

- Llisterri Caro JL, Rodriguez Roca GC, Alonso Moreno FJ, Banegas Banegas JR, Gonzalez-Segura Alsina D, Lou Arnal S, et al. [Control of blood pressure in Spanish hypertensive population attended in primary health-care. PRESCAP 2006 Study]. Med Clin (Barc). 2008;130: 681–7.

- Llisterri Caro JL, Rodriguez Roca GC, Alonso Moreno FJ, Lou Arnal S, Divison Garrote JA, Santos Rodriguez JA, et al. [Blood pressure control in Spanish hypertensive patients in Primary Health Care Centres. PRESCAP 2002 Study]. Med Clin (Barc). 2004;122:165–71.

- Steinberg BA, Bhatt DL, Mehta S, Poole-Wilson PA, O’Hagan P, Montalescot G, et al. Nine-year trends in achievement of risk factor goals in the US and European outpatients with cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2008; 156:719–27.

- Hill MN, Han HR, Dennison CR, Kim MT, Roary MC, Blumenthal RS, et al. Hypertension care and control in underserved urban African American men: behavioral and physiologic outcomes at 36 months. Am J Hypertens. 2003; 16:906–13.

- Woollard J, Burke V, Beilin LJ, Verheijden M, Bulsara MK. Effects of a general practice-based intervention on diet, body mass index and blood lipids in patients at cardiovascular risk. J Cardiovasc Risk. 2003;10:31–40.

- Garcia-Pena C, Thorogood M, Armstrong B, Reyes-Frausto S, Munoz O. Pragmatic randomized trial of home visits by a nurse to elderly people with hypertension in Mexico. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1485–91.

- Devine EC, Reifschneider E. A meta-analysis of the effects of psychoeducational care in adults with hypertension. Nurs Res. 1995;44:237–45.

- Starkey C, Michaelis J, de Lusignan S. Computerised systematic secondary prevention in ischaemic heart disease: a study in one practice. Public Health. 2000;114:169–75.

- Green BB, Cook AJ, Ralston JD, Fishman PA, Catz SL, Carlson J, et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring, Web communication, and pharmacist care on hypertension control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:2857–67.

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, Nordstrom B, Cretin D, Svarstad B. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 1998;36:1138–61.

- Kastarinen MJ, Puska PM, Korhonen MH, Mustonen JN, Salomaa VV, Sundvall JE, et al. Non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension in primary health care: a 2-year open randomized controlled trial of lifestyle intervention against hypertension in eastern Finland. J Hypertens. 2002;20: 2505–12.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78.

- Williams GC, Quill TE, Deci EL, Ryan RM. “The facts concerning the recent carnival of smoking in Connecticut” and elsewhere. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:59–63.

- Murchie P, Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Simpson JA, Thain J. Secondary prevention clinics for coronary heart disease: four year follow up of a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326:84.

- Delaney EK, Murchie P, Lee AJ, Ritchie LD, Campbell NC. Secondary prevention clinics for coronary heart disease: a 10-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Heart. 2008;94:1419–23.

- Feste C, Anderson RM. Empowerment: from philosophy to practice. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;26:139–44.

- McManus RJ, Mant J, Roalfe A, Oakes RA, Bryan S, Pattison HM, Hobbs FD. Targets and self monitoring in hypertension: randomised controlled trial and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2005;331:493.

- Puffer S, Torgerson D, Watson J. Evidence for risk of bias in cluster randomised trials: review of recent trials published in three general medical journals. BMJ. 2003; 327:785–9.

- Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328:702–8.

- Drevenhorn E, Bengtson A, Allen JK, Saljo R, Kjellgren KI. Counselling on lifestyle factors in hypertension care after training on the stages of change model. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;6:46–53.

- Wood DA, Kotseva K, Connolly S, Jennings C, Mead A, Jones J, et al. Nurse-coordinated multidisciplinary, family-based cardiovascular disease prevention programme (EUROACTION) for patients with coronary heart disease and asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a paired, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1999–2012.

- Carlsson AC, Wandell PE, Journath G, de Faire U, Hellenius ML. Factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension and cardiovascular risk in hypertensive 60-year-old men and women– a population-based study. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:780–5.