Abstract

Objectives. To examine causes of death for men above 80 years of age, and health status in centenarians in a cohort of men followed from age 50 years. Factors of importance for survival were studied. Design. A representative sample of men born in 1913 was first examined in 1963 and re-examined at ages 54, 60, 67, 75, 80 and 100 years. Results. Of 973 selected men, 855 (88%) were examined at age 50, and 10 were alive at age 100.Twenty-seven percent lived until 80 years. Cardiovascular disease was the most common cause of death after this age. Dementia was recorded in two of ten men at age 100. Long survival was related to the mothers' high age at death, to non-smoking, high social class at age 50 and high maximum working capacity at age 54 years. At age 100, the seven examined men had low/normal blood pressure. Serum values of troponin T, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptides and C-reactive protein were elevated, but echocardiographic findings were normal. Conclusions. Ten men experienced their 100th birthday. Survival was related to non-smoking, mothers' high age at death, high social class and previous high physical working capacity. Age-adjusted reference levels for laboratory tests are needed for centenarians.

Introduction

A study of men born in 1913 was started in 1963 by the late professor Gösta Tibblin. A representative 1/3 sample of all 50-year-old men living in Gothenburg, Sweden (n = 973) was selected, with 855 men (88%) attending the first examination. Re-examinations were performed at 54, 60, 67, 75, 80 and 100 years of age.

Many studies have been published on risk factors for coronary heart disease. Our first study was a multivariable analysis of risk factors for myocardial infarction in 1973 (Citation1), and a study in 2011 looked into factors of importance for reaching 90 years, as 111 men did (Citation2).

It has long been held that genetic factors play a major role for reaching high age (Citation3). Genetic mapping was not available in the present study, but the age at death of the men's parents, which might be regarded as a proxy of the importance of various genetic factors for reaching old age, was included in the general questionnaire used on different occasions. The follow-up until age 90 years (Citation2) indicated that a high age at death of the mother, but not the father, was of importance, but this was only seen in the univariable and not in the multivariable analysis. Factors of importance for reaching 90 years were non-smoking, low-to-moderate coffee consumption, low serum cholesterol, and good physical working capacity at age 54 years. In addition, having paid high rent for a flat or owing a house at age 50 (as a proxy for having a good financial standing) was of importance (Citation2).

The main objectives of the present study were to analyse factors at age 50 years that predicted living to age 100 years, factors measured at age 80 years that were of importance for survival to age 100, and to analyse health status at age 100 years.

Methods

All examinations until 80 years of age were performed at the unit of Preventive Medicine at the Sahlgrenska or Östra hospitals in Gothenburg, Sweden. The final examination at age 100 years was performed at the home of the men. At that time, a questionnaire was answered on previous and present diseases and hospitalisations since the examination at age 80 years in 1993. Examination of the heart and chest, blood pressure and general habitus, including photography of the face and body were performed (LWilh). A venous blood sample was drawn for analyses of haemoglobin, total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptides (NTproBNP), high sensitive troponin T (hsTnT) and high sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

In addition, an echocardiographic evaluation was performed with a Siemens P50 mobile unit. The patients were examined in the left recumbent position, and the same investigator performed all examinations (MD). Parasternal short-axis and long-axis images as well as apical 3- and 4-chamber views were recorded, and colour and continuous Doppler examinations of the mitral, tricuspid and aortic valves were performed. The diastolic diameter of the left ventricle and the thickness of the interventricular septum were measured in diastole from a parasternal long-axis projection. The ejection fraction was estimated visually.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee at the University of Gothenburg.

Statistics

Conventional statistical methods were used. For the multivariable analysis of factors of importance for mortality from 50 to 100 years we used a Cox regression model or a Poisson regression analysis (Citation4,Citation5) as previously discussed in reference (Citation2). At age 100 years, only ten men were still alive, reducing the statistical power and possibly leading to loss of significance for some variables that were analysed at age 90 years (Citation2). By using a Poisson analysis, taking all deaths during the follow-up into account, this problem could be decreased (Citation5).

Results

Mortality

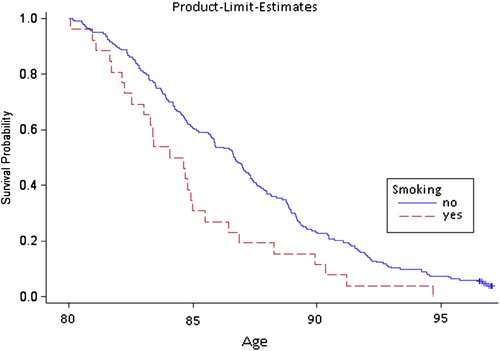

Twenty-seven percent (232/855 men) of the original cohort of men lived until 80 years of age and 13% (n = 111) reached 90 years. Among those who died between 90 and 100 years, 78% died before 95 years of age. Survival curves from age 80 by smoking habits are given in . Causes of death after age 80 were the following: heart disease 42%, of these 25% were coded as ischaemic heart disease; stroke and degenerative cerebral disease, 8%; malignant disease, 6%; pneumonia, 13% and other infectious diseases, 7%. Dementia was recorded in 23% of the men from 80 to 100 years, and of these, 7% were recorded in combination with somatic comorbidity.

Follow-up between 50 and 100 years of age

At Poisson analysis of follow-up from age 50 to 100 years the following factors were significant: Time since age 50, Smoking, High social class, Maximum work capacity, Mothers' age at death. It was furthermore found, last line in , that importance of Mothers' age at death decreased significantly by time.

Table I. Significant variables at multivariable Poisson analysis during follow-up from 50 to 100 years.

Examination at 100 years of age

In total, ten men (1% of the original sample) experienced their 100th birthday. Two men declined to participate in the examination, one of these and another man suffered from dementia and consent could not be obtained; thus, seven men were examined. One man lived with his wife and another lived alone in a house of his own. The other men lived in senior residencies. Data from the examination including laboratory data are presented in .

Table II. Findings at examination and laboratory tests in seven men aged 100 years.

None of the seven men smoked. All the men were well oriented in time and situation. All used hearing aids, and most of the men wore glasses and could read books and watch television. All had a mobility aid (a walker). In general, the men were slim and had rather good carriage. Upon direct questioning and in the discussion it appeared that all the men were satisfied with their lives and living conditions.

One man had drug-treated diabetes mellitus and was also treated with simvastatin due to elevated lipid levels. His LDL cholesterol was 2.2 mmol/L. No other men had elevated cholesterol levels (). Another man was treated for prostatic carcinoma and also for hypertension, and his blood pressure was now 130/70 mmHg.

It is noteworthy that six of the seven men had elevated high-sensitive troponin T, that would, if conventional cut-offs were used, indicate ongoing myocardial infarction, and five out of seven had elevated NTproBNP, which might indicate heart failure (). All men had normal left ventricular function (see below), why other reasons must be considered for the elevation of NTproBNP. All the men but one had high levels of hsCRP, which may indicate low-grade inflammation.

Table III. Biomarkers in seven men aged 100 years.

Echocardiography at age 100

The findings are summarised in . The ejection fraction was visually normal in all, and a common finding was a certain degree of hypertrophy of the inter-ventricular septum, as well as a minor grade 1–2/4 insufficiency of the aortic valve. No other relevant deviations were observed, and no men had localised hypo-or akinesis of the left ventricle.

Table IV. Findings at echocardiography in seven men aged 100 years.

Six of the seven men were in sinus rhythm, whereas one man had permanent atrial fibrillation, present for more than ten years. In addition, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation was known to be present in one man, although he was in sinus rhythm at the time of the examination. None of the men used oral anticoagulants.

Discussion

Cardiovascular disease caused considerable mortality between 80 and 100 years of age, whereas cancer was less common than anticipated at this age. According to official Swedish statistics, there has been a continuous increase in survival over recent years, and it has been projected that about 50% of today's children will live until 100 years of age. Some of this improvement may be due to reduced risk factor levels, such as lower rates of tobacco smoking, lower cholesterol levels and possibly better treatment of hypertension, as well as better medical care in general. However other factors, such as better socioeconomic standards may also contribute to longer survival in the future. An important finding is that tobacco smoking was a strong risk factor, not only for cardiovascular disease but also for total mortality up to 100 years. In the present study, seven out of ten men were examined at age 100 years, and none of the men was regarded as suffering from dementia. However, two of the three non-examined men were suffering from dementia. All of the seven examined men enjoyed life and were happy with their living conditions. Their somatic condition was rather good and the cardiovascular risk factors were relatively low. In particular, we did not see any elevation of blood pressure with increasing age, which goes against the old saying that “normal blood pressure is 100 + age.”

Nominally pathological laboratory findings were observed for several of these otherwise healthy men, indicating that “normal” values may have to be adjusted for age. An increasing number of 100-year-old men would otherwise be over-diagnosed. Upon hospital admission or at the GP's office, blood sampling showed anaemia in five out of seven men. Three men had sufficiently elevated troponin T levels to suspect myocardial infarction. Three men had marked elevation of NTproBNP, which, in combination with symptoms from the chest, would possibly lead to a diagnosis of heart failure. This clearly illustrates the need for age-adjusted reference laboratory levels for the very old. This will be even more important with the increasing number of aged people in the community.

Survival into high age of the men was related to survival of the mother, but not to the father, why survival to some extent seems to be genetically determined. We also found non-smoking, high social class at age 50 years, as well as good physical working capacity at age 54 to be significant predictors of very long survival in multivariable analysis. Our findings support the study by Rantanen et al. (Citation6), who showed that mother's age at death was significantly related to survival to age 100 years among men in the Honolulu Heart Program, and that non-smoking men and those with good handgrip strength lived longer than other men. The relationship between mother's, but not father's survival, and off-spin longevity could neither be explained in the Honolulu study nor in the present one. It is of interest that a Danish large study (Citation3) found sex differences in genetic variation related with survival to high age, but still the pathway leading to this difference is not known.

Conclusion

Non-smoking continued to be the strongest protective factor for longevity, whereas cancer was relatively rare in the very high age. A high social class, non-smoking, a mother living to high age and a good physical working capacity were predictors of long survival of the men. The relationship with the mothers' age at death indicates that genetic factors play a role for the longevity.

We are thankful to the late Prof. Gösta Tibblin, who started the study, and the late Mrs. Inga-Lisa Ljungberg, who was of great administrative help during many years. We also thank RN Görel Hultsberg-Olsson and RN Helena Dellborg for help with the 100-year examination and Georg Lappas MSc and Prof. Anders Odén, PhD, for help with the statistics.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no declarations of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Wilhelmsen L, Wedel H, Tibblin G. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1973;48: 950–8.

- Wilhelmsen L, Svärdsudd K, Eriksson H, Rosengren A, Hansson P-O, Welin C, et al. Factors associated with reaching 90 years of age; a study of men born in 1913 in Gothenburg, Sweden. J Intern Med. 2011;269:441–51.

- Sörensen M. Genetic variation and human longevity. Dan Med J. 2012;59: B4454.

- Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. p 162.

- Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical method in cancer research. Vol. 12. No 32. Lyon: IARC Scientific Publications; 1987.

- Rantanen T, Masaki K, He Q, Ross GW, Willcox BJ, White L. Midlife muscle strength and human longevity up to age 100 years: a 44-year prospective study among a decedent cohort. Age 2012;34:563–70.