Abstract

Objective: To explore the explanatory power of a self-determination theory (SDT) model of health behaviour change for hearing aid adoption decisions and fitting outcomes. Design: A quantitative approach was taken for this longitudinal cohort study. Participants completed questionnaires adapted from SDT that measured autonomous motivation, autonomy support, and perceived competence for hearing aids. Hearing aid fitting outcomes were obtained with the international outcomes inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA). Sociodemographic and audiometric information was collected. Study sample: Participants were 216 adult first-time hearing help-seekers (125 hearing aid adopters, 91 non-adopters). Results: Regression models assessed the impact of autonomous motivation and autonomy support on hearing aid adoption and hearing aid fitting outcomes. Sociodemographic and audiometric factors were also taken into account. Autonomous motivation, but not autonomy support, was associated with increased hearing aid adoption. Autonomy support was associated with increased perceived competence for hearing aids, reduced activity limitation and increased hearing aid satisfaction. Autonomous motivation was positively associated with hearing aid satisfaction. Conclusion: The SDT model is potentially useful in understanding how hearing aid adoption decisions are made, and how hearing health behaviour is internalized and maintained over time. Autonomy supportive practitioners may improve outcomes by helping hearing aid adopters maintain internalized change.

Hearing impairment is one of the most common chronic health conditions among older adults (Gopinath et al, 2012) and, when left untreated, has been associated with diminished psychological health (Kramer et al, Citation2002) and reduced quality of life (Dalton et al, Citation2003). Various intervention options are available to address the consequences of hearing impairment (Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2011) and for suitable candidates, hearing aid fitting has been demonstrated to help (Vuorialho et al, Citation2006). However, despite advances in technology designed to assist people with hearing impairment, it is human behaviour that accounts for the largest variance in decisions made and outcomes reached by people with hearing impairment (Meyer et al, Citation2014; Hickson et al, Citation2014). The decision to obtain hearing aids for the first time, for example, is influenced by attitudes and beliefs about hearing impairment (Meyer et al, Citation2014). Similarly, successful use of hearing aids can be attributed to factors such as positive attitudes toward hearing aids, perceived self-efficacy for handling of hearing aids, and the extent of family support (Hickson et al, Citation2014).

Audiological literature suggests that behavioural factors are influential throughout the hearing rehabilitation process. To maximize the likelihood that those who may benefit from hearing aid fitting take up hearing aids, and then maintain successful outcomes, several theoretical approaches to health behaviour change in hearing rehabilitation research have been investigated (Saunders et al, Citation2013; Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2013; Meyer et al, Citation2014; Ridgway et al, Citation2015). However, questions remain about how behavioural factors might advance insight into the impact of psychological, cognitive, and social aspects of human behaviour on the regulation of hearing health decisions.

One approach, self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, Citation1985), is a theory of motivation that explores the ways a person initiates and sustains new health-related behaviours. SDT characterizes motivation by the extent to which a person has internalized (i.e. accepted as one’s own) ideas and values associated with behaviours (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). The theory predicts that internalized perspectives of health-related behaviour will drive positive changes to that behaviour (Ryan et al, Citation2008). In our overview of SDT (Ridgway et al, Citation2013), different forms of motivation were classified along an internalization continuum, and were described according to the relative autonomy experienced towards health behaviours. Autonomous motivation (i.e. participation in treatment is perceived as self-determined behaviour) is critical to the internalization process through which a person comes to engage with and maintain health behaviour conducive to improved quality of life and wellbeing (Ryan et al, Citation2008). By contrast, controlled motivation, in which client participation arises from susceptibility to external pressure or an internal sense of guilt or obligation, is considered a less internalized motivation source.

Our previous study (Ridgway et al, Citation2015), which was the first to research SDT in hearing rehabilitation, investigated if motivation was associated with adults’ decisions whether or not to adopt hearing aids. A total of 253 first-time hearing help-seekers completed the treatment self-regulation questionnaire (TSRQ; Williams et al, Citation1996), which was adapted to assess autonomous and controlled motivation for hearing aid adoption. After accounting for sociodemographic and audiometric factors, we showed a positive association between autonomous motivation and hearing aid adoption. Controlled motivation did not influence adoption.

SDT focuses on psychosocial processes to help explain behavioural determinants that might influence actions and emotions associated with health behaviour (Ryan et al, Citation2008). Specifically, three psychological needs fundamental for ongoing health and well-being are described: autonomy (feeling self-determination of one’s own decisions and behaviour), competence (feeling capable of attaining health outcomes), and relatedness (feeling understood and respected by others, including the practitioner). SDT health research provides evidence that client-centred practitioners who facilitate autonomy, competence and relatedness can foster healthier long-term self-management of chronic health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and obesity in patients, which can then improve quality of life (Ng et al, Citation2012). Facilitating these needs is commonly referred to in SDT literature as ‘autonomy support’ and has been commonly measured with the health care climate questionnaire (HCCQ; Williams et al, Citation1996). The SDT model of health behaviour change, therefore, argues that people who willingly participate in health treatment and who are provided with an autonomy supportive health care environment will have their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfied to a greater degree, which will in turn result in greater engagement with and maintenance of positive health behaviours, as well as improved psychosocial outcomes (Ryan et al, Citation2008).

To address whether SDT is an applicable model for understanding hearing health behaviour change, we expanded our previous study by introducing autonomy support to the list of variables used to explore hearing aid adoption. We also continued the previous study longitudinally to investigate the role of motivation and autonomy support in maintaining hearing health behaviours over time. The international outcome inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA; Cox et al, 2002); a self-report measure of behavioural and psychosocial outcomes for hearing aid adopters, and the perceived competence scale (PCS; Williams et al, Citation1998a); a psychological measure of perceived competence, were introduced as outcome variables. Therefore, the overall purpose of this study was to provide insight into the psychosocial processes and motivational factors that influence a person to initiate and maintain behaviour change, so that practitioners might better understand the ways clients make decisions in hearing health care, and also how clients internalize beliefs and skills for change.

The aims of the present study were (1) To explore associations between autonomy support and hearing aid adoption (i.e. engagement with hearing health behaviour), and (2) To investigate associations between both autonomy support and autonomous motivation and hearing aid fitting outcomes (i.e. establishment and maintenance of hearing health behaviour), from the perspective of SDT.

Possible confounding variables associated with hearing aid adoption and with hearing aid fitting outcomes (age, four-frequency average hearing level in the better ear, desire for hearing aids, perceived difficulty, gender, and referral source) were controlled for in the analysis so that the specific influence of autonomy support and autonomous motivation could be examined.

Method

Participants

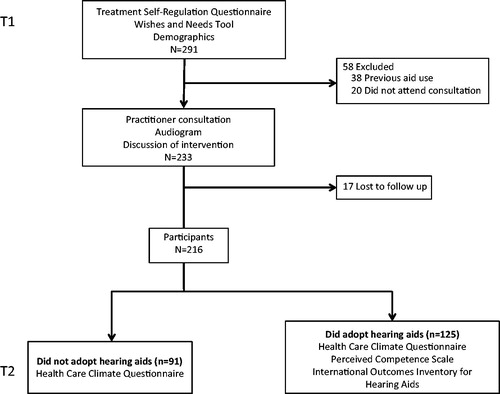

Adult hearing help-seekers were recruited from among 3347 individuals who had attended hearing promotion events, or who had directly sought services from an audiology clinic, and had been provided or sent research material (see Ridgway et al, Citation2015). Eligible participants had no previous hearing aid experience, did not live in residential aged-care facilities, and had sufficient English to understand and respond to study materials. Participants had consulted with a hearing care practitioner at least once, and participated in the study regardless of whether or not they received hearing aids following consultation. At least one consultation was required so that participants could report their perceptions of autonomy support for the duration of rehabilitation. Participants who had completed the treatment self-regulation questionnaire (TSRQ) prior to consultation, but who did not consult with a practitioner, were excluded, as they could not provide health care climate questionnaire (HCCQ) data. A total of 291 potential participants consented to the study, of whom 38 had previous hearing aid experience and were excluded. A further 20 were excluded because they did not consult with a practitioner, and 17 more were lost to follow-up (12 did not respond to repeat requests to complete the HCCQ, four had moved address, and one refused further contact). The final sample consisted of 216 participants (109 female, 107 male) aged between 40 and 95 years (mean 69.6 years, SD 10.47). Among this group, 125 participants adopted hearing aids and 91 did not. shows participant characteristics. Participants were from all states and territories of Australia, and 96% were recruited from a large, Government-owned, multi-site audiology service.

Table 1. Summary data showing participant characteristics as means and standard deviations (or counts and percentages) for the total sample, and classified as hearing aid adopters and non-adopters, along with statistical test results comparing adopters and non-adopters.

Measures

Three self-report questionnaires from the SDT health care package (http://www.selfdeterminationtheory.org/questionnaires) were used: the treatment self-regulation questionnaire (TSRQ; Williams et al, Citation1996); the health care climate questionnaire (HCCQ; Williams et al, Citation1996); and the perceived competence scale (PCS; Williams et al, Citation1998a). For some questionnaire items, words associated with medical treatment, such as ‘medication’ or ‘diabetes’, were substituted with ‘hearing’, ‘hearing aids’, or ‘communication’ where appropriate. Additional questionnaires measuring desire for hearing aids, perceived hearing difficulty, and hearing aid fitting outcomes were included. Participants were asked to provide their age, gender, and referral source (self/spouse or family member/doctor/other). Participant audiograms were also obtained where possible.

Treatment self-regulation questionnaire

The treatment self-regulation questionnaire (TSRQ; Williams et al, Citation1996) was used to assess motivation. It consists of 13 items that represent possible reasons for considering hearing aid adoption. Respondents are asked to rate how true each item was to them on a 7-point Likert scale that range from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). The psychometric properties of a TSRQ adapted for hearing help-seekers were reported in Ridgway et al (Citation2015). The two-factor TSRQ solution derived by Ridgway et al (Citation2015) comprised four ‘autonomous motivation’ items and nine ‘controlled motivation’ items. Examples of autonomous items were ‘I’ve carefully thought about hearing aids and believe that getting them is the right thing to do,’ and ‘I personally believe that doing something about my hearing will improve my quality of life.’ Examples of controlled items were ‘I would be ashamed of myself if I didn’t’, and ‘I think other people would be upset with me if I didn’t.’ Autonomous and controlled motivation scores were calculated by averaging the responses to the items in each subscale.

Health care climate questionnaire

The health care climate questionnaire (HCCQ; Williams et al, Citation1996) was used to measure perceptions of practitioner autonomy support. The 15-item HCCQ has a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), except for item 13, which is reverse coded. Items measure perceived support for autonomy (e.g. ‘My practitioner has provided me choices and options’), competence (e.g. ‘My practitioner has made sure I really understand hearing loss and what I need to do’), and relatedness (e.g. ‘I feel trust in my practitioner’). The HCCQ scores were calculated by averaging individual item scores after item 13 was reversed. Thus, higher HCCQ scores indicated higher perceived autonomy support. Principal component analysis of the HCCQ in this study yielded a one-factor, 15-item solution (Eigenvalue 10.54), consistent with previous research (Williams et al, Citation1998b; Markland & Tobin, Citation2010). All factor loadings were between .67 and .92 and the Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient was .97. The one-factor structure suggested autonomy, competence, and relatedness measured by the HCCQ were interrelated and can be distilled into a single autonomy support variable (Markland & Tobin, Citation2010).

Wishes and needs tool

The wishes and needs tool (WANT; Dillon, Citation2012) was designed to measure desire for hearing aids and perceived hearing difficulty. The WANT has a 5-point Likert scale, and consists of two items: ‘How strongly do you want to get hearing aids’ (1 Don’t want them; 2 Slightly want them; 3 Want moderately; 4 Want them quite a lot; 5 Want them very much), and ‘Overall, how much difficulty do you have hearing (without hearing aids)?’ (1 No difficulty; 2 Slight difficulty; 3 Moderate difficulty; 4 Quite a lot of difficulty; 5 Very much difficulty). Higher scores on the two WANT items indicate greater desire for hearing aids and greater perceived hearing difficulty respectively. The WANT was originally included in our research because of its use in the Australian Government Hearing Services Program 1 as a tool to evaluate motivation.

Perceived competence scale

The perceived competence scale (PCS; Williams et al, Citation1998a) is a 4-item instrument that measures feelings of competence for the applicable health care domain, and was modified to encompass hearing aid use (e.g. ‘I feel confident in my ability to cope with wearing hearing aid/s’). The PCS has a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). Individual items were averaged to obtain an overall score, with higher PCS scores indicating higher perceived competence for hearing aids. The PCS can be administered alongside domain-specific outcomes to allow links between treatment outcome and motivational influences (Williams et al, 2004). Previous health research has supported the internal consistency and construct validity of a single-factor PCS, and Cronbach’s alpha has been consistently above 0.84 (Williams et al, Citation1998a; Fortiera et al, Citation2007). The current study supported a single-factor structure with an Eigenvalue of 3.17. All factor loadings were between 0.76 and 0.96 and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

International outcomes inventory for hearing aids

The international outcome inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA; Cox et al, 2002) was used to measure domains of hearing aid fitting outcome. This inventory has seven items that cover (1) use, (2) benefit,(3) residual activity limitation, (4) satisfaction, (5) residual participation restriction, (6) impact on others, and (7) quality of life. The IOI-HA has a 5-point scale with response options that vary for each item, and is scored by averaging individual item scores, with higher scores indicating better outcome. The IOI-HA is an internationally recognized questionnaire of hearing aid fitting outcomes, and IOI-HA data have been widely reported (Hickson et al, Citation2010). Factor analysis of the IOI-HA has usually reported a two-factor structure (Kramer et al, Citation2002; Cox & Alexander, Citation2002; Öberg et al, Citation2007) with Cronbach’s alpha above 0.78 (Öberg et al, Citation2007). Items 1, 2, 4, and 7 form a ‘personal dimensions’ factor, and items 3, 5, and 6 form an ‘environmental dimensions’ factor. This grouping contrasts with the SDT behaviour change model that distinguishes between behavioural outcomes such as not smoking or healthier eating, and psychosocial outcomes such as less depression or improved quality of life (Ng et al, Citation2012), both of which are regarded as vital to optimizing psychological need satisfaction and optimal health outcomes. Therefore, this study did not perform factor analysis of the IOI-HA and investigated each of the seven outcome domains separately.

Procedures

Ethical clearance for this study was granted by the University of Queensland Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee, which complied with the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007).

outlines participant flow through the four-month study period. A total of 216 participants provided consent and completed the baseline questionnaires (T1), consulted with a practitioner at their chosen audiology clinic, and decided to adopt or not adopt hearing aids. A total of 150 responses were received to the follow-up questionnaires at T2 (response rate 69.4%).

All participants received subsidized hearing services through the Australian Government Hearing Services Program. If suitable, hearing aids of various styles with the following features were available free to participants: automatic directional microphone (for behind-the-ear hearing aids), feedback cancellation, adaptive noise reduction, multi-channel compression, multi-memory, and telecoil. Participants could also access hearing aids with additional features by contributing towards a ‘top-up’ cost. The specific hearing aid type or style fitted to adopters was not sought. Eighty-two percent of participants were fitted bilaterally.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata version 13 software (College Station, USA). Prior to the main analyses, participant characteristics were described with means and standard deviations for continuous variables and count and percentage for categorical variables. Missing data were treated as missing and not imputed. Associations between autonomy support and hearing aid adoption were explored using t-tests, χ2 tests, and multivariate logistic regression. Independent variables were autonomy support (HCCQ scores), autonomous and controlled motivation (TSRQ scores), desire for hearing aids and perceived difficulty (WANT scores), age, gender, referral source, and four-frequency average hearing level in the better ear (4FAHL 22; measured at 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz).

Associations between autonomy support, autonomous motivation and hearing aid fitting outcomes were investigated with pairwise correlations of the aforementioned independent variables and with multiple linear regression. Outcome variables were perceived competence (PCS scores) and the seven IOI-HA items (i.e. IOI-HA scores for use, benefit, residual activity limitation, satisfaction, residual participation restriction, impact on others, and quality of life). Post-estimation tests were performed to check the fit of the regression models.

Results

Autonomy support and hearing aid adoption

To explore univariate associations between autonomy support and hearing aid adoption versus non-adoption, characteristics of adopters and non-adopters were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. The t-test and χ2 results comparing autonomy support and other independent variables for the 125 adopters and 91 non-adopters are shown in . Multivariate regression showed autonomous motivation, perceived difficulty, and 4FAHL were significantly associated with hearing aid adoption (see ). Autonomy support was not significant at the univariate level, which means that autonomy support appears to be unrelated to the adoption decision. Because the inclusion of autonomy support in the regression model did not change the pattern of associations between independent variables and hearing aid adoption reported in Ridgway et al (Citation2015), the multivariate logistic regression analysis was discontinued.

Autonomous motivation, autonomy support, and outcomes

To explore associations between autonomy support, autonomous motivation and hearing aid fitting outcomes, data for the 125 adopters (see ) were subjected to a series of multiple linear regression analyses to explore associations between autonomous motivation, autonomy support and outcomes in that group. Pairwise correlations among sociodemographic, audiometric, and motivation variables were calculated for adopters (), and revealed a relationship between autonomous motivation and autonomy support (r = 0.27, p = 0.01). A high correlation coefficient may indicate collinearity is present, which could mean the variables need to be modeled in separate regression equations. Therefore, variables were tested for collinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF). All VIFs ranged between 1.01 and 1.70, which indicated low collinearity. Consequently, all variables, including autonomous motivation and autonomy support, were retained for the regression analyses, and modeled together rather than separately. In all, eight regression models were formed. Autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, autonomy support, gender, referral source, 4FAHL, age, desire for hearing aids, and perceived difficulty were tested against perceived competence (PCS scores) and each of the seven IOI-HA outcomes. Each variable listed in was screened for inclusion in its respective model with simple regression, then added into the multiple model if p < 0.1. Simple regression showed referral source and 4FAHL were not associated with any outcome and were dropped from the final analyses. Two of the eight outcomes (participation restriction and impact on others) were also dropped, as neither was significantly associated with any variable.

Table 2. Descriptive data of perceived competence scale (PCS) and international outcomes inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA) scores for hearing aid adopters.

Table 3. Matrix for pairwise correlation coefficients (r) showing linear relationships among independent variables for hearing aid adopters (N = 125).

The remaining six multiple regression models were checked for heteroscedasticity using the Breusch-Pagan test (Breusch & Pagan, Citation1979). The presence of heteroscedasticity can invalidate linear regression models by incorrectly assuming equal variance and normal distribution of statistical errors. If heteroscedasticity is detected, regression may be run using robust standard errors to correct for misspecification (White, Citation1980). Three heteroscedastic models (perceived competence, activity limitation, satisfaction) were run with the robust test. The normality of the distribution of residuals was examined using quantile-quantile plots (Wilk & Gnanadesikan, Citation1968). All distributions were essentially linear which suggested normality was a reasonable assumption. For each analysis, outliers from the dataset were identified using the studentized residual (Cook & Weisberg, Citation1982) with absolute values ≥2.58 removed. Three outliers were removed from the activity limitation model, two outliers were removed from each of the perceived competence, use, benefit, and satisfaction models, and no outliers were identified for the quality of life model. shows the regression models of factors associated with each outcome. The results of each analysis are described in turn below.

Table 4. Regression models of factors associated with each outcome of interest.

Perceived competence

Multiple regression revealed 37.12% of the variability in PCS scores was explained by autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, autonomy support, age, desire for hearing aids, and perceived difficulty (R2 = 0.37, F (6, 69) = 5.89, p <0.001). When examining the predictive ability of individual variables, autonomy support was the only variable significantly associated with perceived competence (β = .58, p <0.001): for every 1-unit increase in autonomy support there was a .58-unit increase in perceived competence after adjusting for other variables in the model.

Use

The regression model for hearing aid use (IOI-HA item 1) showed age, desire for hearing aids, and perceived difficulty explained 28.98% of variance in scores (Adjusted R2 = 0.29, F (3, 69) = 10.79, p < 0.001). Perceived difficulty (β = .42, p = 0.001) and younger age (β = −.25, p = 0.02) were the two variables significantly associated with increased use. Each 1-point increase in use score indicated a .42-point increase in perceived difficulty score and a reduction in age of .25 years.

Benefit

For the hearing aid benefit (IOI-HA item 2) model, 38.49% of variance in scores was explained by autonomous motivation, autonomy support, age, desire for hearing aids and perceived difficulty (Adjusted R2 = 0.38, F (5, 65) = 9.76, p <0.001). The two significant individual variables associated with increased benefit were perceived difficulty (β = .33, p = 0.009) and younger age (β = −28, p = 0.007). For each 1-unit increase in benefit there was a .33-unit increase in perceived difficulty score and a reduction in age of .28 years.

Activity limitation

Regression indicated 9.87% of variance in activity limitation scores (IOI-HA item 3) was explained by autonomy support, gender, and age (R2 = 0.10, F (3, 73) = 4.11, p = 0.010). The only variable significantly associated with reduced activity limitation was autonomy support (β = .22, p = 0.006). There was a .22-unit increase in autonomy support for each 1-unit increase in reduced activity limitation.

Satisfaction

For the hearing aid satisfaction (IOI-HA item 4) model, autonomous motivation, autonomy support, age, desire for hearing aids, and perceived difficulty explained nearly half (49.81%) the variability in hearing aid satisfaction scores (R2 = 0.50, F (5, 64) = 13.71, p < 0.001). The two variables significantly associated with hearing aid satisfaction were autonomous motivation (β = .32, p = 0.025) and autonomy support (β = .48, p < 0.001). For every 1-point increase in satisfaction, autonomous motivation increased by .32 points and autonomy support increased by .48 points.

Quality of life

The quality of life (IOI-HA item 7) model revealed autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, autonomy support, age, desire for hearing aids, and perceived difficulty explained 23.22% of variance in scores (Adjusted R2 = 0.23, F (6, 67) = 4.68, p < 0.001). No individual variable showed significant association with quality of life.

In summary, autonomy support was not associated with the decision to adopt or not adopt hearing aids. However, hearing aid adopters who perceived greater autonomy support were significantly more likely to report higher perceived competence, reduced activity limitation, and increased satisfaction. Autonomous motivation was positively associated with satisfaction.

Discussion

The current study investigated associations between autonomy support and hearing aid adoption, and between autonomous motivation, autonomy support, and eight outcomes of hearing aid fitting, from an SDT perspective. As with our previous study (Ridgway et al, Citation2015), autonomous motivation was associated with increased hearing aid adoption. Assessing autonomous motivation could therefore help identify suitable candidates for hearing aid adoption. No association was found between autonomy support and hearing aid adoption. However, autonomy support was significantly associated with increased perceived competence, reduced activity limitation, and increased hearing aid satisfaction. Autonomous motivation was positively associated with hearing aid satisfaction.

That no association arose between autonomy support and hearing aid adoption should be considered alongside our previous results (Ridgway et al, Citation2015), which framed hearing aid adoption as initiation of a particular new, internalized health-related behaviour that stemmed from autonomous motivation. Unlike other SDT health studies that reported positive associations between autonomy support and changes in autonomous motivation in health-related behaviours for chronic conditions such as diabetes or obesity (see Ng et al, Citation2012), autonomy support did not influence hearing aid adoption in this study. This could be because autonomy supportive environments that offer options other than hearing aid fitting, and minimize pressure to adopt hearing aids, might reduce the theoretical association between autonomy support and hearing aid adoption. Hearing aid fitting is not the only new health behaviour that people with hearing impairment might adopt in supportive hearing healthcare environments. Laplante-Lévesque et al (Citation2011) offered people the choice of hearing aids, individual or group programs and no intervention within a shared decision-making paradigm. In the Laplante-Lévesque et al sample, 54.0% chose to be fitted with hearing aids, 24.4% individual or group programs, and 21.6% no intervention. In the present study, we have focused on the health behaviour of hearing aid adoption and do not know whether other forms of intervention were offered and, if they were, what outcomes were obtained. However, research suggests that offering options other than hearing aid fitting is not commonplace (Grenness et al, 2015). Should a variety of intervention options have been available, autonomy support for the intervention decision itself, rather than adoption of hearing aids, may explain the similar autonomy support scores for adopters and non-adopters. Further investigation of the relevance of these findings to behaviour change in hearing rehabilitation is warranted.

For hearing aid fitting outcomes, autonomy support was positively associated with perceived competence, reduced activity limitation, and satisfaction. That is, adopters who perceived their practitioners to be more autonomy supportive were more likely to feel confident and capable with hearing aids, report less difficulty with hearing aids, and report that getting them was worth the trouble. The inverse was also true for adopters who perceived less autonomy support. Hickson et al (Citation2014) reported that two key contributors to hearing aid success were greater confidence when handling advanced aspects of hearing aids and positive attitude. Alongside this finding, our study’s results highlight similarities between the constructs of perceived competence and self-efficacy and their importance to hearing aid success. Furthermore, SDT suggests high levels of perceived competence do not motivate behaviour change; rather, autonomy supportive environments that facilitate perceived competence are required (Markland et al, 2005). The positive association between autonomy support and perceived competence in this study therefore supports the SDT model by acknowledging the practitioner’s role in enabling hearing aid competence for some participants.

Autonomy support, however, was not associated with the hearing aid outcomes: use, residual participation restriction, impact on others, benefit or quality of life, although associations with increased benefit (p = 0.07) and improved quality of life (p = 0.11) neared significance. In the broader SDT health literature, autonomy support has provided small to moderate positive effects across a range of physical and mental health outcomes (Ng et al, Citation2012). For chronic health conditions, results have varied. For example, Hurkmans et al (2010), in a cross-sectional study of 213 participants with rheumatoid arthritis who had attended outpatient clinics, reported participants’ perceptions of autonomy support from rheumatologists did not predict increased physical activity. Conversely, in a large-scale study of patients receiving health care for diabetes, Williams et al (Citation2009) reported that autonomy support was positively associated with autonomous self-management of medication, which in turn was positively associated with perceived competence for diabetes self-management. Differences in populations investigated, the time at which autonomy support was measured, and whether or not autonomy support targeted single or multiple practitioners may account for some portion of the mixed findings. Moreover, sociodemographic factors that contributed to outcomes, such as age, desire for hearing aids, and perceived difficulty, may have reduced the strength of contribution of motivation variables to outcomes in this study. Outcomes measured four months after hearing aid adoption may not represent long-term maintenance of behaviour change, and may affect comparison with long-term outcomes studied in other chronic health conditions (e.g. Williams et al, Citation2009). This is acknowledged as a potential limitation of this study. Nevertheless, on balance, our results support the value of SDT to explore relations between autonomy support and several dimensions of hearing aid fitting outcome. Results from a longitudinal study of a larger sample of hearing aid owners may clarify the significance of associations between autonomy support and non-significant variables.

Our findings also provide some evidence for client-centredness in hearing health care because autonomy support is measured from the client’s perspective. Autonomy supportive environments have much in common with the client-centred approach to health care, wherein practitioners support acquisition of autonomy, competence, and relatedness by encouraging client perspectives and initiatives, providing clear rationales for change, supporting choice, and minimizing pressure (Williams et al, Citation2009; Markland & Tobin, Citation2010). Both clients and practitioners value client-centredness in hearing health care, yet in practice it is not always observed (Grenness et al, 2014; Preminger et al, 2015). With this in mind, our finding that autonomy support was not associated with hearing aid adoption, yet was associated with several outcomes, suggests client-centredness in hearing health care may be less evident when decisions to adopt or not adopt hearing aids are made, and more evident when support is provided for psychosocial factors that facilitate hearing aid competence, activity, and satisfaction. The divergence in findings between hearing aid adoption and outcomes also highlights differences in the processes that underpin health behaviours such as adoption, and psychosocial outcomes such as hearing aid satisfaction. Tailored interventions that acknowledge and address these differences are important. Further research to link autonomy support with client-practitioner interactions would be beneficial, not just for hearing aid adopters, but also for non-adopters, whose outcomes were not explored in this study. Such research could also help identify whether the number of consultations helps strengthen the client-practitioner relationship over time, which may then influence perceptions of autonomy support.

Interestingly, hearing aid satisfaction was the only outcome positively associated with autonomous motivation, such that adopters with higher autonomous motivation were more likely to report that getting hearing aids was worth the trouble. This result provides only limited support for the SDT model. Most SDT health studies have reported direct associations between autonomous motivation and a variety of improved physical and mental health outcomes across disciplines, although effect sizes were usually small (Ng et al, Citation2012). A possible explanation for the lack of association between autonomous motivation and all but one outcome could be that the cohort of hearing aid adopters was highly autonomously motivated initially. A sample mean TSRQ score of 5.94 on a scale of 1 to 7 (Ridgway et al, Citation2015) could suggest there were ceiling effects with the data. Indeed, Mildestvedt et al (Citation2007) found that among highly motivated groups of coronary heart disease patients (mean TSRQ score of 6.2), autonomous motivation had marginal effects on outcomes of dietary changes and smoking cessation.

A more likely explanation for the limited relationships between autonomous motivation and outcomes may relate to the time point at which autonomous motivation was assessed. The current study measured autonomous motivation before participants consulted with their practitioners, thus before autonomy support was assessed but not afterwards. This contrasts with other SDT health studies, which have measured autonomous motivation before and following collection of autonomy support data (Ng et al, Citation2012). Therefore, a causal relationship between autonomy support and autonomous motivation cannot be inferred in this study because any possible effect on autonomous motivation by the practitioner was not measured. To ascertain interrelationships among SDT variables and hearing health care, a larger study that tests pathways among autonomous motivation, autonomy support, perceived competence, and hearing health decisions and outcomes would be of benefit.

Conclusion

In summary, the SDT model was shown to be potentially useful for understanding how hearing health behaviour is internalized and maintained over time. This study found that autonomy support—a core component of the SDT model of health behaviour—was not associated with hearing aid adoption. This implies that client engagement with hearing health behaviour (i.e. hearing aid adoption) was not influenced by the practitioner. Autonomy support was, however, positively associated with perceived competence, reduced activity limitation, and increased satisfaction in hearing aid adopters. Autonomous motivation was only associated with one outcome, hearing aid satisfaction. Autonomy supportive hearing health care settings may therefore help hearing aid adopters maintain internalized skills for change. To gain further insight into the ways that SDT can be applied in the clinical setting, research to explore interrelations among components of SDT, and the nature of how people engage with hearing health behaviours from a SDT perspective, is warranted.

| Abbreviations | ||

| 4FAHL | = | 4-Frequency average hearing loss |

| HCCQ | = | Health care climate questionnaire |

| IOI-HA | = | International outcomes inventory for hearing aids |

| PCS | = | Perceived competence scale |

| SDT | = | Self-determination theory |

| TSRQ | = | Treatment self-regulation questionnaire |

| VIF | = | Variance inflation factor |

| WANT | = | Wishes and needs tool |

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the principal author’s PhD, and was supported through the University of Queensland School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences. The authors would like to thank Dr Asad Khan from the University of Queensland School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, who provided statistical guidance. The authors also wish to acknowledge the support of Australian Hearing, National Hearing Care, and John Pearcy Audiology for their assistance with participant recruitment, and thank the participants for their individual contributions to the study.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No external financial assistance was received for this study. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Notes

1 Notes

The Australian Government Hearing Services Program subsidizes the provision of hearing services to eligible Australians. More information: http://www.hearingservices.gov.au

2 The 4FAHL was adopted in this study to be consistent with World Health Organization Grades of hearing impairment. See http://www.who.int/pbd/deafness/hearing_impairment_grades/en/ for more information.

References

- Breusch T.S. & Pagan A.R. 1979. A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica, 47, 1287–1294.

- Cook R.D. & Weisberg S. 1982. Residuals and Influence in Regression. New York: Chapman and Hall.

- Cox R.M. & Alexander G.C. 2002. The International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA): Psychometric properties of the English version. Int J Audiol, 41, 30–35.

- Dalton D.S., Cruickshanks K.J., Klein B.E., Klein R., Wiley T.L. & Nondahl D.M. 2003. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist, 43, 661–668.

- Deci E.L. & Ryan R.M. 1985. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum Publishing Co.

- Deci E.L. & Ryan R.M. 2000. The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq, 11, 227–268.

- Dillon H. 2012. Hearing Aids (2nd Ed.). Sydney, Australia: Boomerang Press.

- Fortiera M.S., Sweet S.N., O’Sullivan T.L. & Williams G.C. 2007. A self- determination process model of physical activity adoption in the context of a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Sport Exerc, 8, 741–757.

- Gopinath B., Schneider J., McMahon C.M., Teber E., Leeder S.R. et al. 2012. Severity of age-related hearing loss is associated with impaired activities of daily living. Age Ageing, 41, 195–200.

- Grenness C., Hickson L., Laplante-Lévesque A. & Davidson B. 2014. Patient-centred care: A review for rehabilitative audiologists. Int J Audiol, 53, S60–S67.

- Grenness C., Hickson L., Laplante-Lévesque A., Meyer C., & Davidson B. 2015. The nature of communication throughout diagnosis and management planning in initial audiologic rehabilitation consultations. J Am Acad Audiol, 26, 36–50.

- Hickson L., Clutterbuck S. & Khan A. 2010. Factors associated with hearing aid fitting outcomes on the IOI-HA. Int J Audiol, 49, 586–595.

- Hickson L., Meyer C., Lovelock K., Lampert M. & Khan A. 2014. Factors associated with success with hearing aids in older adults. Int J Audiol, 53, S18–S27.

- Hurkmans E.J., Maes S., de Gucht V., Knittle K., Peeters A.J. et al. 2010. Peeters A.J. et al. 2010. Motivation as a determinant of physical activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res, 62, 371–377.

- Kramer S.E., Kapteyn T.S., Kuik D.J. & Deeg D.J. 2002. The association of hearing impairment and chronic diseases with psychosocial health status in older age. J Aging Health, 14, 122–137.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2011. Predictors of rehabilitation intervention decisions in adults with acquired hearing impairment. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 54, 1385–1399.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2013. Stages of change in adults with acquired hearing impairment seeking help for the first time: Application of the transtheoretical model in audiologic rehabilitation. Ear Hear, 34, 447–457.

- Markland D., Ryan R.M., Tobin V.J. & Rollnick S. 2005. Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. J Soc Clin Psychol, 24, 811–831.

- Markland D. & Tobin V.J. 2010. Need support and behavioural regulations for exercise among exercise referral scheme clients: The mediating role of psychological need satisfaction. Psychol Sport Exerc, 11, 91–99.

- Meyer C., Hickson L., Lovelock K., Lampert M. & Khan A. 2014. An investigation of factors that influence help-seeking for hearing impairment in older adults. Int J Audiol, 53, S3–S17.

- Mildestvedt T., Meland E. & Eide G.E. 2007. No difference in lifestyle changes by adding individual counselling to group-based rehabilitation RCT among coronary heart disease patients. Scand J Public Health, 35, 591–598.

- Ng J.Y.Y., Ntoumanis N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani C., Deci E.L., Ryan R.M. et al. 2012. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci, 7, 325–340.

- Öberg M., Lunner T. & Andersson G. 2007. Psychometric evaluation of hearing specific self-report measures and their associations with psychosocial and demographic variables. Audiol Med, 5, 188–199.

- Ridgway J., Hickson L. & Lind C. 2013. Self-determination theory: Motivation and hearing aid adoption. J Acad Rehabil Audiol, 46, 11–37.

- Ridgway J., Hickson L. & Lind C. 2015. Autonomous motivation is associated with hearing aid adoption. Int J Audiol, 54, 476–484.

- Ryan R.M., Patrick H., Deci E.L. & Williams G.C. 2008. Facilitating health behavior change and its maintenance: Interventions based on self- determination theory. Eur Health Psychol, 10, 2–5.

- Saunders G.H., Frederick M.T., Silverman S. & Papesh M. 2013. Application of the health belief model: Development of the Hearing Beliefs Questionnaire (HBQ) and its associations with hearing health behaviors. Int J Audiol, 52, 558–567.

- Vuorialho A.P., Karinen P. & Sorri M. 2006. Effect of hearing aids on hearing disability and quality of life in the elderly. Int J Audiol, 45, 400–405.

- White H. 1980. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–838.

- Wilk M.B. & Gnanadesikan R. 1968. Probability plotting methods for the analysis of data. Biometrika, 55, 1–17.

- Williams G.C., Grow V.M., Freedman Z.R., Ryan R.M. & Deci E.L. 1996. Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. J Pers Soc Psychol, 70, 115–126.

- Williams G.C., Freedman Z.R. & Deci E.L. 1998a. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care, 21, 1644–1651.

- Williams G.C., Rodin G.C., Ryan R.M., Grolnick W.S. & Deci E.L. 1998b. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychol, 17, 269–276.

- Williams G.C., Niemiec C.P., Patrick H., Ryan R.M. & Deci E.L. 2009. The importance of supporting autonomy and perceived competence in facilitating long-term tobacco abstinence. Ann Behav Med, 37, 315–324.