Abstract

Objective: To assess (1) the feasibility of incorporating the Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools into a UK audiology service, (2) the potential benefits of motivational engagement in first-time hearing aid users, and (3) predictors of hearing aid and general health outcome measures.

Design: A feasibility study using a single-centre, prospective, quasi-randomized controlled design with two arms. The Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools formed the basis for motivational engagement. Study sample: First-time hearing aid users were recruited at the initial hearing assessment appointment. The intervention arm underwent motivational engagement (M+, n = 32), and a control arm (M-, n = 36) received standard care only. Results: The M+ group showed greater self-efficacy, reduced anxiety, and greater engagement with the audiologist at assessment and fitting appointments. However, there were no significant between-group differences 10-weeks post-fitting. Hearing-related communication scores predicted anxiety, and social isolation scores predicted depression for the M+ group. Readiness to address hearing difficulties predicted hearing aid outcomes for the M- group. Hearing sensitivity was not a predictor of outcomes. Conclusions: There were some positive results from motivational engagement early in the patient journey. Future research should consider using qualitative methods to explore whether there are longer-term benefits of motivational engagement in hearing aid users.

Hearing loss causes increased communication difficulties, which often results in reduced activity and participation in everyday life, leading to social withdrawal, depression, and reduced quality of life (Davis et al, Citation2007; Heffernan et al, Citation2016). The most common management intervention for people with hearing loss is the fitting of hearing aids (HAs). In the UK, around 2 million people have HAs, however a reported 30% of these do not wear them regularly (Davis, Citation2003; AoHL, Citation2015), despite the introduction of digital HAs in 2000. It is becoming increasingly apparent that HA fitting alone is not the optimum intervention for people with hearing loss, and success with HAs could be improved by adopting additional strategies (Beck et al, Citation2007; Sweetow et al, Citation2007).

One such strategy is motivational engagement (ME) (Rubak et al, Citation2005). The benefits of ME have been recognized for many years in other disciplines whereby the technique has been successfully applied to smoking cessation (e.g. Clark, Citation2008), alcohol addiction (e.g. DiClemente et al, Citation1999), and drug rehabilitation programs (e.g. Leon et al, Citation1997). More recently, the principles of ME have been applied to people with hearing loss (Beck & Harvey, Citation2009; Aazh, Citation2015). The Ida Institute has developed Motivation Tools, models, and strategies designed to support, engage and coach HA users in order to improve their readiness and self-efficacy, uptake, acceptance, and successful use of HAs (Clark, Citation2010). The Motivation Tools are based on the theoretical principles underlying the transtheoretical model (TTM) of health behaviour change (Prochaska & DiClemente, Citation1986). This model posits six stages of health behaviour change, which applied to HAs are: precontemplation (not yet considered there is a hearing-related problem), contemplation (thinks HAs might be needed), preparation (started to seek information about HAs), action (ready to receive HAs), maintenance (comfortable with the idea of wearing HAs), and relapse (stops wearing HAs). Contemplation and preparation are part of the attitude process, whereas action, maintenance, and relapse are part of the behaviour process.

The application of the TTM to people with hearing loss in terms of the stages of change has been demonstrated to have good construct, concurrent and predictive validity by Laplante-Lévesque et al (Citation2013). These authors investigated the stages of change in 153 adults who were seeking help with their hearing loss for the first time. Uptake of two interventions (HAs and a communication program), outcome measures at three months, and intervention adherence at six months were assessed. The majority of participants were initially in the action stage, and those in the advanced stages of change were more likely to take-up and report greater success with their chosen intervention. It was noted however, that stages of change did not predict adherence to the intervention. Furthermore, the study concluded that change may be better represented on a continuum rather than by discrete stages.

Adults seeking help for their hearing loss generally see their encounters and interactions with audiologists as isolated events within a disconnected process (Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2012). A better understanding of where the patient lies within the rehabilitation process and their motivations underlying help-seeking may improve HA adoption and patient outcomes. This was shown in a recent study, based on the self-determination theory of motivation (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008), where autonomous motivation was associated with HA adoption (Ridgway et al, Citation2015). Although addressing motivations to promote help-seeking behaviour and HA adoption is best achieved by taking a patient-centred approach, this was shown to rarely occur in a sample of 62 video-recorded hearing assessment sessions (Grenness et al, Citation2015). ME facilitated by use of motivational tools to help guide the audiologist and patient is one potential approach to enhance patient-centred interactions within the audiology clinic.

The Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools are intended for use by the audiologist during a clinic appointment to help open a dialogue with patients and to better engage them in the rehabilitation process (Clark, Citation2010). By better understanding the patient’s motivations for help-seeking and where the patient is at in the stages of change, the audiologist can work collaboratively with the patient. This helps the patient to enter into a dialogue that is intended to facilitate a decisional balance by exploring their own ambivalence, understanding their own decision-making process, and preparing them for accessing resources to manage behaviour change. In the case of first-time HA users this includes improving patient’s self-acceptance and use of their HAs by engaged listening, appropriate guidance, encouragement, and reassurance from the audiologist.

At the time that the study was conceived, there were no published studies on either the feasibility or the efficacy of the Motivation Tools in clinical practice. Although there was interest in the tools in the UK, there were uncertainties about whether it was possible to incorporate the tools in to standard UK clinical practice, in particular due to time constraints. Similarly, it was not clear which outcome measures would be appropriate and sensitive to evaluate any potential benefits of the tools. As a first step, we chose to carry out a feasibility study in a sample of first-time HA users to bettr understand how the tools might be used in a UK publicly funded National Health Service (NHS) clinic, and to assess how their potential benefits might be evaluated. This approach is consistent with the MRC guidelines for evaluating complex interventions (Medical Research Council, Citation2008). Having established these, it was anticipated that future studies would evaluate the effectiveness of the tools when used with people who had yet to make a decision about future interventions, such as HAs. In addition, a number of studies have observed non-audiological factors such as self-efficacy, positive attitudes, support from communication partners, and autonomous motivation were associated with HA adoption and outcomes in retrospective samples (e.g. Ridgeway et al, Citation2013, Citation2015). We were therefore interested to assess which audiological and non-audiological factors might predict outcomes in first-time HA users.

The aims of the this study were to (1) assess the feasibility of incorporating the Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools into a UK NHS audiology service, (2) evaluate the potential benefits of using ME with first-time HA users in terms of HA and general health outcomes, and (3) identify predictors of HA and general health outcome measures.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited prospectively from Nottingham Audiology Services (NAS). The inclusion criteria were (1) first-time HA users, (2) age greater than 18 years, (3) better-ear pure-tone average thresholds (BEA) greater than 20 dB HL across octave frequencies between 0.25 to 4 kHz (British Society of Audiology, Citation2011), and (4) native English speaking or good understanding of English. The exclusion criterion was an inability to complete the questionnaires due to age-related problems, such as cognitive decline and dementia, based on the audiologist’s opinion. A total of 68 participants met the eligibility criteria and were fitted with HAs, with 53 (78%) attending the 10-week follow-up evaluation session.

Study design and procedure

The feasibility study used a single-centre, prospective, quasi-randomized design with two arms. The intervention arm underwent ME (M+, n = 32), and a control arm (M-, n = 36) received standard care only. Patients were randomly allocated for an initial hearing assessment appointment to one of five study-nominated audiologists (two M+ and three M-) by the NAS administrators. Patients who met the eligibility criteria at the assessment appointment were invited by the audiologist to participate in the study. Informed, written consent was obtained at the HA fitting appointment approximately four weeks post-assessment to meet the ethical requirements of at least a 24-hour consideration period. Participants attended a follow-up evaluation session (M+, n = 28; M-, n = 25) 10-weeks post-fitting (mean = 10.69, SD = 3.4). Although it was not always possible for participants to see the same audiologist at each visit, they always saw an audiologist allocated to the relevant arm.

Improved HA benefit is a potential outcome of ME, and so benefit measured by the Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile, widely used in the UK, was considered the primary outcome measure to define the sample size. In order to detect an increase in HA benefit of 12.5%, based on 80% power and a 2-sided type I error rate of 5%, 27 patients were required in each group. Allowing for attrition of 20%, the study aimed to recruit 65 patients, which was achieved, although at follow-up, the M- group fell two participants short of the required 27.

The research protocol was approved by the East Midlands Research Ethics Committee, and Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust Research and Innovation department. Participants were paid a nominal inconvenience fee and travel expenses for the follow-up session.

The intervention

Motivation tools

The Motivation Tools include The Line, Box and Circle. The Line tool asks two questions. The first (LQ1) asks ‘How important is it for you to improve your hearing right now?’, and aims to help patients assess their own motivations and readiness to improve their hearing. The second (LQ2) asks ‘How much do you believe in your ability to use a hearing aid?’, and aims to help patients assess their self-efficacy for HAs and identify any fears or lack of confidence. Patients are asked to select a number on an unmarked visual analogue scale between 0 (not important/unable) to 10 (of highest importance/able) to reflect their own situations. By asking why the patient chose their score and encouraging patients to raise and evaluate their own stories, the audiologist can work collaboratively with the patient on matters that are important and relevant to them.

The Box asks the patient to consider and weigh up the benefits and costs of taking no action against the potential benefits and costs of taking action. Again, this is based on the patient’s own experiences, motivations, and reflections, shared between themselves and the audiologist to help engage both in a patient-focused discussion.

The Circle provides a visual representation of patients’ readiness to receive hearing care recommendations, derived from a combination of self-assessment from the patient and the audiologist’s own observations. Based on the TTM (Prochaska & DiClemente, Citation2005), the Circle represents the stages of change. The Circle can help guide the audiologist as to the patient’s readiness to receive and take-up hearing care recommendations, such as HAs, as well as guide clinical interactions, including offering information, advice, encouragement, and support. Unlike the other tools, the Circle is not necessarily shared with patient, and in this study, the audiologists did not share this information.

Training audiologists to use the motivation tools

Two experienced audiologists (NR, EB) were trained on the theoretical principles of ME, the TTM of behaviour change, and the use of the Motivation Tools by two members of the Ida Institute (senior audiologist, MG, and anthropologist, Hans Henrik Philipsen). This took place as part of a three-day participatory workshop, which included training on practical aspects of using the Motivation Tools with first-time HA patients during clinic appointments. Each audiologist practiced using the tools on 2–3 patients per session, for three sessions. After each patient, the audiologist discussed appointments with MG, reflecting on what they had learned. Both clinic appointments and the post-appointment discussions were filmed by Hans Henrik Philipsen. Post-clinic, sections of film footage were then reviewed by the audiologists and other members of the research team, guided by the Ida Institute team. This provided an opportunity for further reflections on the training and learning process, as well as the audiologist’s thoughts about how the tools could be best utilized in the clinic (see ). This iterative process was repeated over two days. The end-product was a 30-minute ethnographic documentary, which was developed for use in training other audiologists and can be viewed online (http://www.hearing.nihr.ac.uk/).

Table 1. Reflections on the clinical use of the Motivation Tools. The participatory workshop revealed a number of take-home messages that are relevant to clinical practice.

Clinically, The Line and Circle were used with all patients, whereas The Box was used if there was a need to highlight ambivalence, based on the audiologist’s judgement. The tools were used at both the assessment and HA fitting appointments. At the assessment appointment, the tools were used during assessment of patient needs (post-audiogram), and at the fitting appointment they were used prior to HA fitting.

Outcome measures

Due to the feasibility nature of the study, a range of outcome measures was used. All questionnaires were completed by the participant at home and returned to the Nottingham Hearing Biomedical Research Unit in a pre-paid envelope, unless specified otherwise.

Hearing assessment appointment

The Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP) (Gatehouse, Citation1999) is a validated self-report questionnaire comprising six subscales that relate to four pre-specified situations and four user-specified situations. The GHABP assesses hearing disability (activity limitations) and handicap (participation restrictions) (part I), and HA use, benefit, residual disability and satisfaction (part II). Each subscale is measured on a five-point scale, and the mean score across the four pre-defined situations was converted into a percentage. Part I was completed at the hearing assessment, and part II was completed for the aided condition at follow-up with the audiologist. The overall outcome score was the mean of the part II subscales (Cronbach’s α =.80, where >.80 indicates good internal consistency).

The Hearing Health Care Intervention Readiness (HHCIR) (Weinstein, Citation2012) is a 10-item questionnaire that includes four subscales: communication (four items), readiness (three items), social isolation (two items), and self-efficacy (one item). Responses were chosen from a three-point scale (0 = no/not very; 2 = sometimes; 4 = yes/very), and summed to provide a separate score for each subscale. The overall score was the sum of the subscales, excluding the Self-efficacy subscale. (Cronbach’s α = .79).

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983) is a 14-item scale to assess psychosocial well-being, comprising two subscales of anxiety and depression. Respondents indicated how they felt in the previous week using a four-point scale (0 = no, not at all, to 3 = yes, definitely). The overall score was the sum of the subscales. The HADS was completed after the assessment (Cronbach’s α = .89) and follow-up (Cronbach’s α = .84) appointments.

The Short Form Patient Activation Measure (PAM) (Hibbard et al, Citation2005) is a 13-item questionnaire that assesses patient knowledge, skills, and confidence for self-management of their health. Respondents indicated how much each statement applied to them on a four-point scale (0 = disagree strongly, to 3 = agree strongly). Summed scores were converted into an activation score between 0–100 (0 = no activation, 100 = high activation). Four levels of activation were derived from these scores: Level 1 (0–47.0) = patient may not yet believe that the patient role is important; Level 2 (47.1–55.1) = patient lacks confidence and knowledge to take action; Level 3 (scores 55.2–67.0) = patient is beginning to take action and engage in recommended health behaviours; and Level 4 (scores 67.1–100) = patient is proactive about their health and is engaging in many recommended health behaviours. The PAM was completed after the assessment (Cronbach’s α = .85) and follow-up (Cronbach’s α = .89) appointments.

Hearing aid fitting appointment

The Audiology Outpatient Survey (AOS) (see supplementary materials: http//www.informaworld.com/(DOI number), Picker Institute Europe, Citation2011) is a nine-item questionnaire derived from an outpatient survey used to routinely evaluate the patient’s experience with the audiologist at the HA fitting appointment. Questions were chosen that had relevance to patient-centred care. Answers to each item were given on a three-point scale (0% = No, 50% = yes, to some extent, 100% = yes, definitely).

Follow-up appointment

The Measure of Audiologic Rehabilitation Self-efficacy for Hearing Aids (MARS-HA) (West & Smith, Citation2007) includes four subscales: basic handling, advanced handling, adjustment to HAs, and aided listening skills. Respondents indicated how confident they were that they could do the things described on an 11-point scale (0% = cannot do this, to 100% = certain I can do this). The overall score was the average of the subscale scores (Cronbach’s α = .88).

The Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life (SADL) (Cox & Alexander, Citation2001) is 15-item measure that comprises four composite scores: positive effect, service and cost, negative features, and personal image. Question 14 (‘Does the cost of your hearing aids(s) seem reasonable to you?’) was omitted, since HAs are provided free of charge by the UK NHS. Each item is scored on a seven-point scale (A = not at all, to G = tremendously), where a high score indicates high satisfaction. The overall score was the average of the subscale scores (Cronbach’s α = .82).

Hearing aid use (average hours/day) using datalogging integral to the HA was downloaded for the period between the fitting and follow-up appointments.

Data analysis

The distributions of scores for each outcome measure were visually and statistically inspected (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p ≥ .05). Means and standard deviations were given, and compared between-groups using univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA). Effect size (Cohen’s d) was categorized as small, moderate, and large for 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 respectively. If scores were skewed, medians and interquartile ranges were reported, and group differences tested non-parametrically using the independent samples Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test. For all analyses using multiple comparison, the p-values were Holm-Bonferroni corrected: a stepwise algorithm that is more powerful than the standard Bonferroni correction (Holm, Citation1979; Aickin & Gensler, Citation1996). Spearman rank correlation coefficients, due to skewed distributions, were used to test associations of assessment and follow-up outcome measures. For all significant correlations (p ≤ .05), simple or multiple linear regression analysis tested whether measures at assessment predicted outcome measure scores at follow-up. Overall scores were always entered as a single predictor into the model. If more than one subscale score was significantly correlated with an outcome measure score, they were both entered into the model in order of significance.

Results

Both groups at assessment were equivalent in terms of age (M+, mean = 71.85 years, SD = 9.7; M-, mean = 70.31 years, SD = 9.8), gender (M+, females= 16; M-, females = 18); hearing threshold (BEA0.25-4 kHz: M+, mean = 35.03 dB HL, SD = 9.5; M-, mean = 35.60 dB HL, SD= 10.5); and GHABP disability (M+, mean = 54.05%, SD = 16.1; M-, mean = 46.64%, SD = 16.5). For these variables, there was no significant between-group difference at assessment or follow-up (p >0.53), nor was there any difference for these variables along with the PAM, Line, and Circle scores between those who did and did not attend the follow-up for each group (p >0.22).

Motivation levels (the line) and stages of change (the circle)

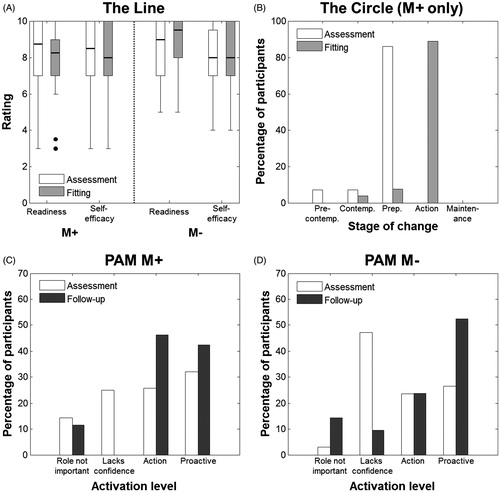

The line

Both Line measures had positively skewed distributions with median scores ≥8 (). For LQ1 (readiness), the ratings at both assessment and fitting appointments showed that the M- group rated their readiness higher than the M+ group, which was significant at the fitting appointment (U = 366, p =.047). The within-group ratings were not significant. Only a small number of participants had ratings at 6 or less at assessment (M+, 13%: M-, 3%) and follow-up (M+, 13%: M-, 6%). For LQ2 (self-efficacy), between-group and within-group ratings were similar, with no significant differences. There were fewer ratings below 6 at assessment (M+, 10%: M-, 23%) and follow-up (M+, 19%: M-, 14%).

Figure 1. (A) Boxplot showing median ratings for The Line questions 1 (Readiness) and 2 (Self-efficacy) at the assessment appointment and fitting appointment for M+ and M- groups. Line questions were used as the intervention with the M+ group, and with the M- group as a simple measure of readiness and self-efficacy only. (B) Percentage of M + participants classified by the audiologist according to one of five stages of change (The Circle) at assessment and fitting appointments. (C) Percentage of M+ participants falling within one of the four PAM Activation levels (see text) at assessment and follow-up. (D) Percentage of M- participants falling within one of the four PAM Activation levels at assessment and follow-up. PAM = Patient Activation Measure.

At assessment, the stages for The Circle (M+ only) showed the majority of individuals (86.2%) were at the preparation stage, indicating that the audiologists assessed most participants were intending to take action in the immediate future (). By the fitting appointment, the majority of participants (89.9%) had moved to the action stage, with only 7.4% remaining at the preparation stage. Therefore most participants were assessed to have made observable modifications to their behaviour in terms of willingness to use HAs between assessment and fitting appointments. The difference observed in stages of change between assessment and fitting was significant (X2(3, N = 28) = 12.29, p = .006).

Outcome measures

Assessment appointment

Group mean (or median) scores for the self-report measures obtained after the assessment and follow-up appointment are shown in .

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation (or median and interquartile range) for self-report measures completed at assessment (HHCIR, HADS, PAM) and follow-up (HADS, PAM, GHABP, SADL, MARS-HA, datalogging), for both M+ (assessment, n = 32; follow-up, n = 28) and M- (assessment, n = 36; follow-up, n = 25) groups. Uncorrected p-value is provided for differences between groups, with bold indicating significance following Holm-Bonferroni correction. HHCIR = Hearing Health Care Intervention Readiness, HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PAM = Patient Activation Measure, GHABP = Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile, SADL = Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life, MARS-HA = Measure of Audiologic Rehabilitation Self-efficacy for Hearing Aids.

For the HHCIR, there was no significant between-group difference for the overall or subscale scores with the exception of the Self-efficacy subscale (U = 283.5, p <.001, d = 0.90), with a large effect size, which remained significant after Holm-Bonferroni correction. Although the median Self-efficacy subscale score for both groups was 4 (very confident to follow recommendations from a healthcare professional), only 59% of the M- group reported they were ‘very confident’, compared to 100% of participants in the M+ group. This suggests that motivational engagement may have improved self-efficacy in terms of confidence to follow the recommendations of the audiologist after the initial assessment appointment. For the HADS, the overall and subscale scores were lower (i.e. better) for the M+ group compared to the M- group, which were significant for Overall (F(1,45) = 5.16, p = .028, d = .68) and Anxiety scores (F(1,45) = 8.14, p = .007, d = .86), with moderate-large effect sizes, which remained significant after Holm-Bonferroni correction. The PAM Activation scores were slightly higher in the M+ group but there was no significant between-group difference. The Activation Levels were similar between groups, shown in , falling between levels 2 (lacks confidence and knowledge to take action) and 3 (beginning to take action).

Fitting appointment

AOS. The median overall score was 100% for both groups, with only 17.2% of the M+ group reporting less than 100% (range = 83–95%), compared to the 35.5% for the M- group (range= 67–95%), which was not significant (U = 354.5, p = .07). Further examination of the individual questions using the Kruskal-Wallis test showed that the responses differed significantly between groups for the following two questions: ‘If you had important questions to ask the health-care professional, did you get answers that you could understand?’ (X2(1, N = 56) = 5.02, p = .025), and ‘Were you involved as much as you wanted to be in decisions about your care and treatment?’ (X2(1, N = 60) = 3.94, p = .047).

Follow-up appointment

Group mean (or median) scores for the self-report measures obtained after follow-up are shown in . The HADS, SADL, and datalogging scores were generally better in the M+ group compared to the M- group, however these differences were not significant. The GHABP and MARS-HA results were similar for both groups. Overall, there were no significant differences between the M+ and M- groups for any of the outcome measures, which suggests that there were no benefits of the ME with these outcome measures 10-weeks post-HA fitting.

Wellbeing and activation across the patient journey

Separate mixed-ANOVAs, with time (assessment, follow-up) as the within-subjects factor, and group (M+, M-) as the between-subjects factor, assessed whether there were any differences for the HADS and PAM. For the HADS, there was no main effect of time or group, or a time × group interaction for overall or subscale scores (p ≥ .37), suggesting that there was no significant between-group differences across time-points. Thus, the lower HADS Overall and Anxiety scores present in the M+ group after the assessment, no longer remained 10-weeks later. For the PAM Activation scores, there was a main effect of time (F(1,43) = 12.78, p = .001, η2ρ =.229, d = 1.09), with a large effect size, but no main effect of group or group × question interaction (p ≥ .72). Thus, irrespective of group, PAM Activation scores significantly increased from assessment to follow-up. Similar results were seen for Levels of Activation, which also showed a main effect of time (F(1,43) = 8.29, p = .006, η2ρ =.162, d = .88), with a large effect size, but no main effect of group, or a group × question interaction (p ≥ .79). Across both conditions, mean PAM Activation Level scores increased from 2.7 (lacks confidence and knowledge to take action) to 3.1 (beginning to take action) from assessment to follow-up, where there were a greater number of participants at Activation Levels 3 and 4 at follow-up than at assessment ().

HADS, PAM, and HHCIR as predictors of follow-up outcomes

Spearman rank correlation coefficients tested whether scores from the HADS, PAM, and HHCIR (overall and subscale scores) completed at assessment were associated with outcome measures completed at follow-up separately for each group. The HADS and PAM scores did not significantly correlate with any hearing or general-health outcome measures, nor did hearing thresholds (p > .05). However, this was not the case for the HHCIR ().

Table 3. Significant (p <.05) Spearman rank (rs) correlation coefficients between HHCIR administered at assessment and outcome measures administered at follow-up for the M+ and M- groups. Bold indicates significance.

For the M+ group, the HHCIR was significantly correlated with the HADS only (Overall, Communication, Social Isolation), with moderate correlations (). Multiple regression analysis showed the HHCIR Overall scores significantly predicted the HADS Overall, Anxiety, and Depression scores (). The HHCIR Communication and Social Isolation scores together accounted for 42% of the variance in HADS Overall scores (F(2,22) = 9.5, p = .001). However, only Social Isolation was a significant predictor. Similar results were shown for the HHCIR Communication and Social Isolation scores, which accounted for 51% of the variance in HADS Depression scores (F(2,21) = 12.71, p < .001). Again, only Social Isolation was a significant predictor. This suggests that for the M+ group it was the experience and perception of social isolation that contributed mostly to the HADS Overall and Depression scores. However, HHCIR Communication scores predicted the HADS Anxiety scores, suggesting that communication difficulties rather than social isolation predicted anxiety.

Table 4. Summary of multiple regression analysis for each outcome measure predicted by HHCIR scores based on significant Spearman rank correlation coefficients, for both M+ and M- groups. Bold indicates significance (p <.05).

A different pattern of results were seen for the M- group. The HHCIR was significantly correlated with GHABP subscale and MARS-HA self-efficacy scores, as well as datalogging, with moderate to large correlations (). The multiple regression analysis showed that the HHCIR Overall scores significantly predicted GHABP Overall, HA Use, Benefit, and Satisfaction scores (). The HHCIR subscales explained 49–63% of the variance in the GHABP outcomes, however only HHCIR Readiness was a significant predictor. Similarly, Readiness also predicted objective HA use in terms of datalogging. The HHCIR Self-efficacy scores significantly predicted the MARS-HA Overall, Aided listening, Basic handling, and Adjustment scores. Taken together, for the M- group readiness to pursue a hearing-healthcare intervention contributed to better HA outcomes, whereas self-efficacy to follow the recommendations of a hearing healthcare professional, as measured by the HHCIR, predicted greater hearing aid self-efficacy.

Discussion

This feasibility study showed that the Motivation Tools could be successfully incorporated into the UK audiology clinic structure, and the audiologists were positive on how they could be used. As the tools were used with those patients who had already opted for hearing aids, the next stage in future research would be to assess the feasibility of using the tools as part of the patient’s decision-making process in adopting an intervention.

In terms of potential benefits of the tools, we demonstrated that at the hearing assessment, the group receiving ME (M+) had greater self-efficacy and reduced anxiety levels compared to the standard clinical care control (M-) group. At HA fitting, the M+ group also responded more positively than the M- group to two questions from an outpatient survey that addressed patient-centred care (whether the patient felt involved in decisions about their care and treatment, and whether the patient received answers to important questions that they could understand). This suggests that the M+ group reported higher levels of shared decision-making and had a better understanding and knowledge of issues around their treatment and care. However, by the 10-week post-fitting follow-up, there were no significant differences between groups for any of the outcome measures, including general health-related measures of wellbeing and activation, in addition to hearing-specific measures of HA benefit, satisfaction, self-efficacy and HA use. As such, any benefits or advantages that those receiving ME appeared to report in the early stages of their patient journey were no longer evident several months later.

There are at least two possible reasons why there was no between-group difference in outcomes at follow-up. One is that the ME did not confer any longer-term patient benefits. The other is that the outcome measures used were not appropriate nor sensitive to any potential benefits of the ME intervention at follow-up. The latter is not just relevant to ME but also applies to other hearing-related interventions (Saunders et al, Citation2005; Ferguson & Henshaw, Citation2015). More recently, qualitative research has emerged as a methodology to gain a more in-depth understanding of the personal perspectives of people with hearing loss, and is being used more frequently in audiological research to provide insights that cannot be achieved by quantitative methods alone (Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2010; Knudsen et al, Citation2012; Ferguson et al, Citation2015; Henshaw et al, Citation2015; Heffernan et al, Citation2016). For example, Ekberg et al (Citation2016) used conversational analysis of video recorded audiologist-patient interactions to identify patients’ readiness in standard hearing assessment appointments. We suggest that in future studies of ME, qualitative methodologies could be used to gain a better understanding of how patients and audiologists respond to ME and to tap into the dynamics of the audiologist-patient interaction.

Our final aim was to assess whether an audiological measure of hearing loss and non-audiological measures of readiness (HHCIR), wellbeing (HADS), and activation (PAM) predicted patient benefit at follow-up. There were no predictive effects of hearing loss, wellbeing or activation. It was noteworthy that the groups showed different results, whereby in the M + group, the HHCIR predicted general health wellbeing, whereas in the M- group the HHCIR predicted HA outcomes. In the M+ group, communication difficulties predicted anxiety, whereas social isolation predicted depression. Although hearing loss is reported to relate to anxiety, depression, and wellbeing (Knutson & Lansing, Citation1990; Heine & Browning, Citation2002) there is little evidence in the literature to demonstrate how social isolation leads to depression in those with hearing loss. However, a review of social isolation in the elderly provides strong evidence that social isolation is associated with poor health outcomes, including mental health and social wellbeing, yet assessment of social isolation in primary care is rare (Nicholson, Citation2012; Steptoe et al, Citation2013). In the M- group, readiness was the strongest predictor for self-reported HA outcomes (GHABP) and objective HA use, which is consistent with other studies (Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2013; Ferguson et al, Citation2016). It is not clear why the pattern of results differed between the groups. We could speculate that psychosocial and general wellbeing issues had been brought to the fore in the M+ group as a result of the ME, whereas there may have been a greater focus on specific HA issues in the M- group. Further research is needed to systematically evaluate this possible dissociation in greater detail.

Patient readiness was also garnered from the audiologist’s use of The Circle tool. At assessment, audiologists assessed the majority of M+ participants as being at the preparation stage, which then shifted to the action stage at HA fitting. It has been suggested that when individuals are in the preparation stage they are already indicating readiness to change in the near future (e.g. 30 days) (Babeu et al, Citation2004). This was seen in our sample where most moved from preparation to action stage between the assessment and fitting appointments (typically four weeks apart). In the UK NHS system, HAs are free of charge, which may also have been a factor in this large shift from preparation to action. Nevertheless, self-efficacy would still have been critical at assessment as people need to believe that they have the ability to make the change, which was indicated in the M+ group. Although the stage of change using The Circle was the audiologist’s perception, this was broadly consistent in the participants’ Activation Levels derived from the PAM, which aims to assess knowledge, skill, and confidence for self-management of an individual’s health. Even though the PAM is a general health measure, significant changes were seen in both groups where lower levels of activation were reported at assessment (1 = patient role not important, 2 = lacks confidence), whereas higher levels of activation were reported at follow-up (3 = action, 4 = proactive). Therefore, as first-time HA users moved through their patient journey, their perception of their knowledge, skills, and confidence in self-management increased. A change in patient readiness is likely to be due to a variety of reasons, including their encounters with the audiologist, and their own informal experiences of learning to use and adjusting to HAs through trial and error (Kramer et al, Citation2005). Provision of additional support, through communication programs (e.g. ACE, Hickson et al, Citation2007), or educational programs for hearing aid users (e.g. C2Hear, based on resusable learning objects, Ferguson et al, Citation2015) may further enhance self-management.

A potential limitation of this study is that unlike interventions that have a tangible and physical presence (i.e. HAs) with clinically measurable output (i.e. amplified sound), we did not have a measure of the dynamics of ME and audiologist-patient interchange in order to demonstrate that first, ME occurred, and secondly, how it was played out. Methods such as the Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC) (Moyers et al, Citation2003) might provide a comprehensive examination of the audiologist-patient interaction and behaviours. Another, more simplified coding system developed from the MISC is the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) (Moyers et al, Citation2003), which provides a means to assess competency and provide feedback to the interviewer (Miller et al, Citation2004). In future research, these methods, alongside those such as video recording the audiologist-patient encounters (see Grenness et al, Citation2015; Ekberg et al, Citation2016), may provide an objective means to assess the role and use of the ME in clinic. Despite an absence of such measures in the study itself, the ethnographic documentary made by the Ida Institute during the workshop provides insights into the training, experiences, and reflections of the audiologists who undertook the ME in this study, which shed some light on how the ME tools might work in clinical practice.

One further limitation is that it is not possible to rule out reasons other than the ME intervention to explain the differences seen at assessment and fitting, despite the quasi-randomized design. For example, it is possible that any differences between the groups may be attributable to the audiologists rather than the ME intervention per se. To avoid such confounds in future research, audiologists could be involved in both the ME and the control arms. However, there was a clear rationale for our approach where only two audiologists were trained in the principles of ME and the use of the Motivation Tools, which was to prevent any introduction of these principles into the standard care that the control group received.

Finally, although the stages of change according to the TTM may be a useful framework to help audiologists visualize patients’ readiness to change, Laplante-Lévesque et al (Citation2013) presented data that suggest change may be better represented on a continuum rather than as discrete stages. Furthermore, it is important to be aware that the model itself, although previously popular in other healthcare fields (e.g. addiction), has been criticized. It is proposed that the model does not describe genuine stages of change, and that precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation can be thought of as arbitrary stages within a larger pre-action stage, whereas action and maintenance are separated only by arbitrary time periods (Sutton, Citation2005). In addition, there is little evidence of progression through the entire stage cycle, nor does it reflect reality (Etter, Citation2005). It is also difficult to apply the model to complex behaviours, as individuals may be at a different stage of change for each of the actions that comprise that complex behaviour (Adams & White, Citation2003; Brug et al, Citation2005). Finally, it has even been argued that the model should be abandoned (West, Citation2005). Although readiness to behaviour change is currently a construct that is receiving attention within the audiological field, it may be better viewed not as a single construct, but rather as a series of tasks and successes that result in change (DiClemente, Citation2005).

Conclusion

This feasibility study explored the use of the Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools as a means to enhance motivational engagement in audiology clinic appointments with first-time HA users. It was feasible to implement motivational tools into clinical practice with appropriate training, and the feedback and reflections from audiologists of the use of the tools in clinical practice was very positive. There were some positive results early on in the patient journey for the group where Motivation Tools were used, who showed greater self-efficacy, reduced anxiety, and greater engagement with the audiologist. However, there was no robust evidence from the outcome measures used in this study that there were any sustained benefits a couple of months later. Future research in motivational engagement methods should consider using qualitative methods to more robustly explore the potential benefits of motivational engagement.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ACE | = | Active Communication Education |

| AOS | = | Audiology Outpatient Survey |

| BEA | = | Better ear average |

| GHABP | = | Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile |

| HA | = | Hearing aid |

| HADS | = | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HHCIR | = | Hearing Health Care Intervention Readiness |

| LQ | = | Line question |

| MARS-HA | = | Measure of Audiologic Rehabilitation Self-efficacy for Hearing Aids |

| ME | = | Motivational engagement |

| M+ | = | Intervention group |

| M- | = | Standard care group |

| NAS | = | Nottingham Audiology Services |

| NHS | = | National Health Service |

| PAM | = | Patient Activation Measure |

| SADL | = | Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life |

| TTM | = | Transtheoretical model. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study audiologists Emily Balmer, Zoe Slinger, Joanne Sisson, and Anna Lindstrand, in particular Emily who was so engaged in the motivational process. We also thank the Nottingham Audiology Service administrative staff and Will Brassington (Head of Audiology). Our grateful thanks to Hans Henrik Philipsen for his expertise and inspiration, and for coaching the team on the principles of the Ida Institute’s Motivation Tools. Finally, we would like to thank Holly Thomas for her help coordinating the study, as well as Sandra Smith and Laura Daley for their help in the data management.

Declaration of interest

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Unit Programme. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Aazh H. 2015. Feasibility of conducting a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of motivational interviewing on hearing-aid use. Int J Audiol, 2, 1–9.

- Adams J. & White M. 2003. Are activity promotion interventions based on the transtheoretical model effective? A critical review. Br J Sport Med, 37, 106–114.

- Aickin M. & Gensler H. 1996. Adjusting for multiple testing when reporting research results: the Bonferroni vs Holm methods. Am J Public Health, 86, 726–728.

- AoHL. 2014. Statistics About Deafness and Hearing. London.

- Action on Hearing Loss . 2015. Statistics about Deafness and Hearing. http://www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/your-hearing/about-deafness-and-hearing-loss/statistics.aspx. Accessed 18th January 2016.

- Audiology Online, September 8, http://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/listening-from-heart-improving-connections-908 Accessed 18th January 2016.

- Babeu L.A., Kricos P.B. & Lesner S.A. 2004. Application of the stages-of-change model in audiology. J Acad Rehabil Audiol, 37, 41–56.

- Beck D.L. & Harvey M.A. 2009. Creating Successful Professional-Patient Relationships Audiology Today: American Academy of Audiology, pp. 36-47.

- Beck D.L., Harvey M.A. & Schum D.J. 2007. Motivational interviewing and amplification. Hear Rev, 14, 14.

- British Society of Audiology 2011. Pure-tone air- and bone-conduction threshold audiometry with and without masking.

- Brug J., Conner M., Harre N., Kremers S., Mckellar S. et al. 2005. The Transtheoretical Model and stages of change: a critique: observations by five commentators on the paper by Adams, J. and White, M. (2004) why don't stage-based activity promotion interventions work? Health Educ Res, 20, 244–258.

- Clark J. 2008. Listening from the heart: Improving connections with our patients. Audiol Online,

- Clark J. 2010. The geometry of patient motivation: Circles, lines, and boxes. Audiol Today, 22, 32–40.

- Cox R.M. & Alexander G.C. 2001. Validation of the SADL questionnaire. Ear Hear, 22, 151–160.

- Davis A. 2003. Population study of the ability to benefit from amplification and the provision of a hearing aid in 55-74-year-old first-time hearing aid users. Int J Audiol, 42, 2S39–32S52.

- Davis A., Smith P., Ferguson M., Stephens D. & Gianopoulos I. 2007. Acceptability, benefit and costs of early screening for hearing disability: a study of potential screening tests and models. Health Technol Assess, 11, 1–294.

- Deci E.L. & Ryan R.M. 2008. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol, 49, 182–185.

- Diclemente C.C. 2005. Conceptual models and applied research: The ongoing contribution of the transtheoretical model. J Addict Nurs, 16, 5–12.

- Diclemente C.C., Bellino L.E. & Neavins T.M. 1999. Motivation for change and alcoholism treatment. Alcohol Res Health, 23, 87–92.

- Ekberg K., Grenness C. & Hickson L. 2016. Identifying older clients’ readiness for hearing rehabilitation in audiology appointments. Int J Audiol, Submitted this issue.

- Etter J.F. 2005. Theoretical tools for the industrial era in smoking cessation counselling: A comment on West (2005). Addiction, 100, 1041–1042.

- Ferguson M., Brandreth M., Leighton P., Brassington W. & Wharrad H. 2015. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the benefits of a multimedia educational programme for first-time hearing aid users. Ear and Hearing, Publ ahead of Print, Nov/Dec 2015.

- Ferguson M.A., Woolley A. & Munro K.J. 2016. The impact of self-efficacy, expectations and readiness on hearing aid outcomes. Int J Audiol, this issue.

- Gatehouse S. 1999. Glasgow hearing aid benefit profile: derivation and validation of. J Am Acad Audiol, 10, 80–103.

- Grenness C., Hickson L., Laplante-Lévesque A., Meyer C. & Davidson B. 2015. The nature of communication throughout diagnosis and management planning in initial audiologic rehabilitation consultations. J Am Acad Audiol, 26, 36–50.

- Heffernan E., Coulson N., Henshaw H., Barry J. & Ferguson M. 2016. Understanding the psychosocial experiences of adults with mild-moderate hearing loss: A qualitative study applying Leventhal’s self-regulatory model. Int J Audiol, Early Online: 1–10.

- Heine C. & Browning C. 2002. Communication and psychosocial consequences of sensory loss in older adults: overview and rehabilitation directions. Disabil Rehabil, 24, 763–773.

- Henshaw H., Mccormack A. & Ferguson M. 2015. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is associated with computer-based auditory training uptake, engagement, and adherence for people with hearing loss. Front Psychol, 6, Article 1067, Pg 1–13.

- Hibbard J.H., Mahoney E.R., Stockard J. & Tusler M. 2005. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res, 40, 1918–1930.

- Hickson L., Worrall L. & Scarinci N. 2007. Active Communication Education (ACE): A Program for Older People with Hearing Impairment. Brackley, United Kingdom: Speechmark.

- Holm S. 1979. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat, 6, 65–70.

- Knudsen L.V., Laplante-Levesque A., Jones L., Preminger J.E., Nielsen C. et al. 2012. Conducting qualitative research in audiology: A tutorial. Int J Audiol, 51, 83–92.

- Knutson J.F. & Lansing C.R. 1990. The relationship between communication problems and psychological difficulties in persons with profound acquired hearing loss. J Speech Hear Disord, 55, 656–664.

- Kramer S.E., Allessie G.H.M., Dondorp A.W., Zekveld A.A. & Kapteyn T.S. 2005. A home education program for older adults with hearing impairment and their significant others: A randomized trial evaluating short-and long-term effects. Int J Audiol, 44, 255–264.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2010. A qualitative study of shared decision making in rehabilitative audiology. J Acad Rehabil Audiol, 43, 27–43.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2012. What makes adults with hearing impairment take up hearing aids or communication programs and achieve successful outcomes? Ear Hear, 33, 79–93.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2013. Stages of change in adults with acquired hearing impairment seeking help for the first time: application of the transtheoretical model in audiologic rehabilitation. Ear Hear, 34, 447–457.

- Leon G.D., Melnick G. & Kressel D. 1997. Motivation and readiness for therapeutic community treatment among cocaine and other drug abusers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 23, 169–189.

- Medical Research Council. 2008. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance: Oxford: Medical Research Council.

- Miller W.R., Yahne C.E., Moyers T.B., Martinez J. & Pirritano M. 2004. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol, 72, 1050–1062.

- Moyers T., Martin T., Catley D., Harris K.J. & Ahluwalia J.S. 2003. Assessing the integrity of motivational interviewing interventions: Reliability of the motivational interviewing skills code. Behav Cogn Psychoth, 31, 177–184.

- Moyers T., Martin T., Manual J. & Miller W. 2003. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico.

- Nicholson N.R. 2012. A review of social isolation: An important but underassessed condition in older adults. J Prim Prev, 33, 137–152.

- Picker Institute Europe. 2011. Outpatient Survey, United Kingdom: Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, Audiological Medicine.

- Prochaska J.O. & Diclemente C.C. 1986. Toward a Comprehensive Model of Change, New York: Springer.

- Prochaska J.O. & Diclemente C.C. 2005. The Transtheoretical Approach. In: J.C. Norcross & M.R. Goldfried (eds.) Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., pp. 147–171.

- Ridgeway J., Hickson L. & Lind C. 2013. Self-determination theory: Motivation and hearing aid adoption. J Acad Rehabil Audiol, 46, 11–37.

- Ridgway J., Hickson L. & Lind C. 2015. Autonomous motivation is associated with hearing aid adoption. Int J Audiol, 54, 476–484.

- Rubak S., Sandbæk A., Lauritzen T. & Christensen B. 2005. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract, 55, 305–312.

- Saunders G.H., Chisolm T.H. & Abrams H.B. 2005. Measuring hearing aid outcomes-Not as easy as it seems. J Rehabil Res Dev, 42, 157

- Steptoe A., Shankar A., Demakakos P. & Wardle J. 2013. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 110, 5797–5801.

- Sutton S. 2005. Another nail in the coffin of the transtheoretical model? A comment on West (2005). Addiction, 100, 1043–1046.

- Sweetow R., Corti D., Edwards B., Moodie S. & Sabes J. 2007. Warning: Do not add on aural rehabilitation or auditory training to your fitting procedures. Hear Rev, 14, 48–51.

- Weinstein B.E. 2012. Geriatric Audiology. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.

- West R. 2005. Time for a change: putting the Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model to rest. Addiction, 100, 1036–1039.

- West R. & Smith S.L. 2007. Development of a hearing aid self-efficacy questionnaire. Int J Audiol, 46, 759–771.

- Zigmond A.S. & Snaith R.P. 1983. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 67, 361–370.