Abstract

Objectives: The transtheoretical model (TTM) of behaviour change focuses on clients’ readiness for adopting new health behaviours. This study explores how clients’ readiness for change can be identified through their interactions with audiologists during history-taking in initial appointments; and whether clients’ readiness has consequences for the rehabilitation decisions they make within the initial appointment. Design: Conversation analysis (CA) was used to examine video-recorded initial audiology appointments with older adults with hearing impairment. Study sample: The data corpus involved 62 recorded appointments with 26 audiologists and their older adult clients (aged 55+ years). Companions were present in 17 appointments. Results: Clients’ readiness for change could be observed through their interaction with the audiologist. Analysis demonstrated that the way clients described their hearing in the history-taking phase had systematic consequences for how they responded to rehabilitation recommendations (in particular, hearing aids) in the management phase of the appointment. In particular, clients identified as being in a pre-contemplation stage-of-change were more likely to display resistance to a recommendation of hearing aids (80% declined). Conclusions: The transtheoretical model of behaviour change can be useful for helping audiologists individualize management planning to be congruent with individual clients’ needs, attitudes, desires, and psychological readiness for action in order to optimize clients’ hearing outcomes.

Introduction

Despite the increasing incidence of hearing impairment (HI) among the older population, as compared to younger adults, audiologists often encounter reluctance to seek professional help (Meyer & Hickson, Citation2012). Further, many older adults who do have their hearing tested do not subsequently go on to obtain hearing aids (Meyer et al, Citation2011). A recent study found that only just over half of clients who were recommended hearing aids within an initial audiology appointment made a commitment to obtain them within that appointment (Grenness et al, Citation2015a). There is also an under-utilization of hearing aids among those who have been fitted with them (Chien & Lin, Citation2012; Gopinath et al, Citation2011; Hartley et al, Citation2010). These findings highlight that help-seeking is not synonymous with a readiness for obtaining and using hearing aids. Older adults who attend audiology appointments to have their hearing tested cannot universally be assumed to be psychologically ready for hearing aids (Claesen & Pryce, Citation2012). They may be attending only to appease others, may not have considered hearing aids as a treatment option, or may consider hearing aids an undesirable option. For such clients, the decision to go ahead with hearing rehabilitation, particularly acquiring hearing aids, requires a major shift in attitudes and behaviour.

Models of health behaviour change can be useful for exploring how people make decisions to change health-related behaviours. One particular model, the transtheoretical model (TTM), views behavioural change as a process that occurs across a number of stages, rather than being a discrete event (Prochaska et al, Citation2009). In viewing behaviour change as a process, the model focusses on an individual’s current attitudes, behaviours, and intentions to assess his/her readiness for change. This model can thus be useful for examining the psychological readiness of clients for hearing rehabilitation when they attend an initial audiology appointment. The model has identified five key stages that an individual will move through in changing their behaviour (although not necessarily occurring in a linear manner). These stages include: (1) pre-contemplation (problem denial or lack of awareness); (2) contemplation (awareness of problem); (3) preparation (intention to change behaviour); (4) action (overt behaviour modification); and (5) maintenance (sustained behaviour change). The model purports that individuals who are in the later stages of change are more likely to succeed at help-seeking, intervention uptake, and adherence. There are three other key constructs in the model, including: decisional balance (the pros and cons of changing); self-efficacy; and processes of change. However, the current paper is focused on identifying clients’ stage-of-change. This model has successfully been applied to various health behaviours including smoking cessation, dieting, depression and anxiety, HIV prevention, sun exposure, and medication compliance (for reviews see Hall & Rossi, Citation2008; Prochaska et al, Citation2009).

The TTM has also been applied within audiology as a way of exploring clients’ readiness for hearing rehabilitation (e.g. Babeu et al, Citation2004; Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2015; Milstein & Weinstein, Citation2002; Raymond & Lusk, Citation2006; van den Brink et al, Citation1996). Babeu et al (Citation2004) described how the different stages of readiness for change can be applied to the audiological rehabilitation setting. For example, a client in the pre-contemplation stage would be unaware, or not yet concerned about, problems with hearing loss (Babeu et al, Citation2004). They may feel that their hearing is fine or that they only have mild difficulties in some situations. Any hearing difficulties they may have might be attributed to environmental factors or third parties (e.g. people who mumble or speak too softly). They would, therefore, be likely to believe that audiological assistance is unnecessary. In the contemplation stage, clients would be aware of a hearing loss and be beginning to have concerns. They would be open to considering options towards hearing rehabilitation. At the preparation stage the client would indicate a readiness to make changes. These clients would be likely to have sought help for their hearing and already thought about hearing rehabilitation options. Then clients at the action stage would take the actual steps toward a commitment to hearing rehabilitation (e.g. purchasing hearing aids and/or agreeing to adopt new communication strategies). In the last stage, maintenance, the client would have integrated their hearing rehabilitation into their life (e.g. sustained use of hearing aids / assistive listening devices, applying self-advocacy strategies).

This model has been shown to have validity in the audiology setting (Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2015). In particular, measurement of the pre-contemplation stage has been shown to have the best concurrent and predictive validity of intervention uptake and outcomes. In a study by Laplante-Lévesque et al (Citation2012), participants who scored highly on pre-contemplation reported less successful intervention outcomes, whereas those who scored highly on action were more likely to have taken up hearing intervention at six months follow-up. The study concluded that measuring clients’ stage-of-change could help audiologists identify clients that are likely to require a different clinical approach. However, they also concluded that the 24-item University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA) used in the study was unlikely to be useful for application in clinical settings because of its length. Thus, while previous studies have demonstrated that a client’s readiness for hearing rehabilitation is an important aspect for consideration during initial audiology appointments, testing their stage-of-change may be difficult in the time-pressured clinic environment. These findings raise the question as to whether clients’ readiness for change can be identified through standard clinical interactions with audiologists within their initial appointments rather than undertaking additional tasks. That is, whether clients’ stage-of-change be recognized through clients’ verbal and nonverbal communication.

This study explores the aforementioned question through an analysis of 62 video-recorded initial audiology appointments with older adults. The paper aims to examine: (1) how clients’ readiness for change can be observed within the history-taking phase of the appointment; and (2) whether this perceived readiness has consequences for their rehabilitation decisions in the management phase of the appointment.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

The current study is part of a broader project that used two types of interaction analysis (Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS) and Conversation Analysis (CA)) to profile and examine video-recorded audiology appointments with older adults with age-related hearing impairment. The data for this study involved a corpus of 62 video-recorded initial hearing assessment audiology appointments, collected during 2011–2013. In this data set, participants are both audiologists (n = 26) and adult clients, aged 55 years and over (n = 62). The age bracket of 55 years or older was a pragmatic cut off for recruitment reasons. In addition, in Australia, those over the age of 55 are more likely to be retired, or semi-retired and therefore potentially have differing motivations and readiness of younger and middle-aged adults. Audiologists who worked in adult hearing rehabilitation settings were invited to participate in this study. After audiologist consent was obtained, clients who fitted the inclusion criteria (over the age of 55 and attending this audiologist for the first time) were also invited to participate by having their audiological consultation filmed. All participants provided signed consent with no form of reimbursement. Participating audiologists had clinical experience ranging from 1 to 40 years and 61% were female; clients were 71.6 years of age, on average (SD 8.9) and 58% were male (Grenness et al, Citation2015a,Citationb).

Filmed appointments were restricted to those that involved a hearing assessment and a discussion about hearing rehabilitation options; or a follow-up appointment where results and rehabilitation options had not been discussed during the first appointment (that is, where the first appointment involved hearing screening or diagnostic testing only). Filming was conducted using an Apple iPhone 4 or iPod touch on a mini tripod without the researcher in the room. After filming, the consultation was uploaded onto a computer. For the analysis reported in this study, consultations were transcribed verbatim with additional notations (as discussed below in analysis). Consultations had an average duration of 57.8 minutes (SD 20.3) wherein the history-taking phase took 8.8 minutes (SD 4.3) on average and 29.0 minutes (SD 18.6) were spent discussing results and management planning (Grenness et al, Citation2015a,Citationb). Audiologists recommended rehabilitation in 83% of consultations where the presence of hearing loss was identified during the appointment (based on audiometric thresholds or presence of significant hearing-related impairment), and all of these recommendations included discussion of hearing aids. Alternative rehabilitation options (e.g. hearing-assistive technology, group or individual communication classes) were recommended in 8% of consultations, and only if the client had already decided against hearing aids (Grenness et al, Citation2015a). Further information regarding participants’ characteristics and the procedure for data collection can be found in Grenness et al (Citation2015a,Citationb). This study was approved by the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, The University of Queensland Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee, and Australian Hearing Human Research Ethics Committee, and adhered to the principles of the National Health and Medical Research Statement on Research Involving Human Subjects.

Data analysis

The video data were transcribed using the Jeffersonian transcription system (Jefferson, Citation2004) to include micro-details of the interaction which have been found to be consequential for how participants understand conversation (see Appendix 1 for transcription notations). The data were analysed using conversation analysis (CA). CA focuses on, and provides conventions for, the analysis of talk as a vehicle for social action (Drew et al, Citation2001; Drew & Heritage, Citation1992; Heritage & Maynard, Citation2006). CA is a well-established approach for studying communication in a range of healthcare settings (Pilnick et al, Citation2009). Studies of healthcare interaction have revealed the ways in which clinicians and clients accomplish interactional tasks such as diagnosing, recommending, and responding to treatment, and address various interactional issues and dilemmas that arise as they undertake these tasks (Pilnick et al, Citation2009). This method has also been used in previous research of communication in audiology appointments, including family involvement in appointments, and how audiologists address clients’ concerns regarding hearing aids (Ekberg et al, Citation2014a,Citationb, Citation2015). During the history-taking phase of the appointment, clients’ responses to audiologists’ questions were analysed for how they described their hearing difficulties. It was identified that clients’ responses during history-taking clearly matched the key descriptions of one of the stages-of-change. Further systematic analysis of the whole corpus was conducted by the lead author (KE) to code each client into a stage-of-change based on the descriptions of their hearing difficulties during history-taking. At the beginning of the audiology appointment, during history-taking, clients could potentially be in one of three stages-of-change according to the TTM: pre-contemplation, contemplation, or preparation (clients may progress to the action stage by the end of the appointment if they decide to obtain hearing aids). Analysis of clients’ responses during history-taking demonstrated that their stage-of-change could be observed through the way they described their hearing difficulties. Some clients displayed an awareness of their hearing difficulties and attributed their problems to a decline in their own hearing. Across the history-taking interaction, these clients could be identified as being at the ‘contemplation’ stage-of-change. Some clients additionally mentioned an intention to obtain hearing aids, and could be identified as being in the ‘preparation’ stage-of-change. Other clients tended to deny or play down their problems, and attributed any difficulties they were having to third parties or environmental factors. From the responses of these clients, they could be identified as being in a ‘pre-contemplation’ stage-of-change. Once the history-taking phase of each appointment had been coded, the management phase of the appointment was analysed for how clients’ responded to rehabilitation recommendations. Transcript fragments are presented in the results section (‘A’ = audiologist; ‘C’ = client; and ‘F’ = family member).

Results

Of the 62 video-recorded appointments, hearing aids were formally recommended in 79% (n = 49) of the assessment appointments. Of these appointments, 61% (n = 30) of clients made a commitment within the appointment to obtain hearing aids and 39% (n = 19) declined hearing aids or decided they needed more time to think about them. In the remaining 21% of consultations, no recommendation of hearing aids was made as clients experienced no self-reported hearing impairment; no hearing loss was diagnosed; or the level of hearing loss was not deemed appropriate for hearing-aid fitting (according to the minimum loss threshold criteria of a three frequency average ≤23 dB).

Conversation analysis of the history-taking phase of the appointments identified 27% of clients to be in a pre-contemplation stage-of-change (n = 17), 65% of clients to be in a contemplation stage-of-change (n = 40), and 8% (n = 5) of clients to be in a preparation stage-of-change.

Analysis also demonstrated that how clients described their hearing in the history-taking phase had systematic consequences for how they responded to rehabilitation recommendations (in particular, hearing aids) in the management phase of the appointment. ‘Pre-contemplation’ clients were much more likely to display resistance to a recommendation of hearing aids. In particular, of those clients who were identified as being in ‘pre-contemplation’ and were subsequently recommended hearing aids, 80% declined (n = 8/10). The two clients who did go ahead with hearing aids agreed to “trial” the fully-subsidized, Government-funded devices. Conversely, 71% (n = 24/34) of clients identified as being in the contemplation stage, and 80% (n = 4/5) of clients identified as being in the preparation stage agreed to obtain hearing aids when offered them. These clients thus successfully transitioned to the action stage across their appointment. These results are presented in .

Table 1. Results of coding clients according to stage-of-change.

The following three sections will analyse, in detail, five examples that were typical of the corpus for how clients displayed their readiness for change, and the consequences it had for the management phase of the appointment.

Client displays ‘pre-contemplation for change’

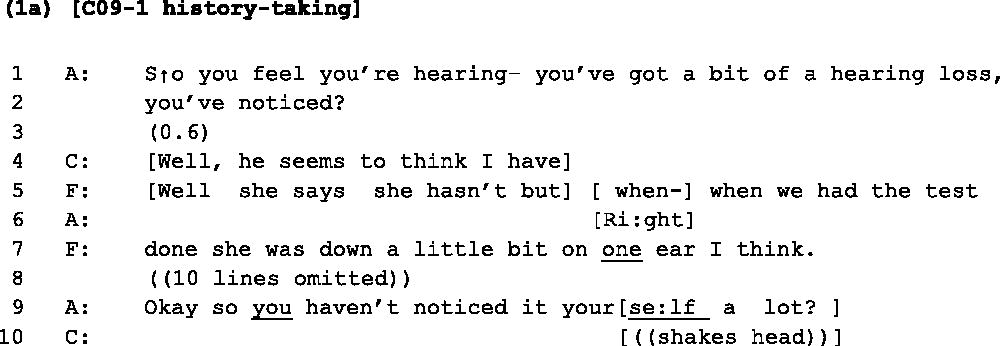

There were appointments where clients revealed that they were unaware of, or not concerned about any hearing difficulties, and this had consequences for their responses to rehabilitation recommendations later on. Fragments (1a) and (1b) provide an example:

In Fragment (1a), in response to the audiologist’s history-taking question, the client denies noticing any hearing difficulties. She states that her husband thinks she has hearing loss (line 4), which is confirmed by her husband in overlap (lines 5 and 7). The client’s turn is marked with several indications of providing a dispreferred response to the audiologist’s question: it is slightly delayed, and contains a turn-initial ‘well’, followed by a sentential response to a yes/no question (Heritage & Raymond, Citation2010; Pomerantz, Citation1984). Later, when asked directly whether she has noticed hearing loss herself, the client shakes her head (line 10). This lack of awareness or concern about her hearing problem would suggest that perhaps the client may still be in the pre-contemplation stage-of-change. These displayed beliefs about her hearing have consequences for the management phase of the appointment, when hearing aids are recommended:

In Fragment (1b), after providing a diagnosis of mild hearing loss, the audiologist suggests hearing aids to the client at lines 1–3. The client responds that ‘no’ she does not really see hearing aids as an option for her (lines 4 and 6). The client’s rejection of the recommendation is produced as an immediate, flat ‘no’ response. When the audiologist begins to take another turn, the client again responds with a ‘no’ (line 6). Following this response from the client, the interaction soon comes to a close and the client leaves without taking any action toward hearing rehabilitation. Fragment (1b) demonstrates how clients reserve themselves the right to reject hearing aids when they do not feel ready for them. Fragments (2a) and (2b) provide another example from another client:

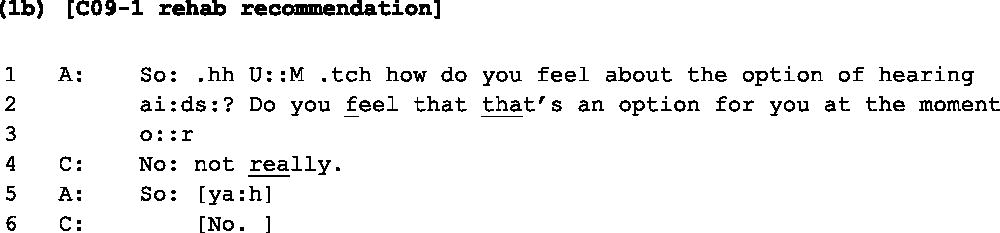

In Fragment (2a), during the history-taking phase, the client expresses that she is not too concerned with her hearing (line 3), launching her turn with an emphatic ‘no not a lot’. As in Fragment (1a), her response is marked with interactional indications of dispreference (Pomerantz, Citation1984). She provides an elongated hesitancy marker ‘mmm::::::’ followed by a ‘no’ response and an account for her low concern. She mentions a mild difficulty in situations of background noise (lines 4–5), playing down her difficulty with the minimizer ‘a bit’. She also attributes troubles with hearing to her granddaughter mumbling and talking ‘very low’ (lines 6–7), but follows on to describe it as ‘not a big problem’. To authenticate her account, the client then provides an example of a situation where she can hear very well (lines 14–17). The client’s responses here display low concern about her hearing difficulties, thus suggesting that she may be in the pre-contemplation stage-of-change. Again, the client’s opinions displayed during the history-taking phase can be seen to be consequential for how she responds to recommended treatment in the management phase (Fragment (2b) below):

Fragment (2b) follows a diagnosis of mild-moderate hearing loss. Across lines 1–7, the audiologist suggests hearing aids would be beneficial and asks the client if this is something she has thought about doing. The client responds that hearing aids are not something she has thought about (line 6), and not something she’s interested in unless ‘she really has to’ (line 8). The audiologist progresses to provide some further information about hearing aids and suggests the client do a trial (omitted from transcript). She then asks the client again if that’s something she would like to do. The client provides several further resistive responses across lines 15–22, stating that she is not keen, does not feel she needs one, and that she can hear. It is interesting that she repeats the phrase ‘I can hear’ which she had originally said to the audiologist during the history-taking phase (see line 19 of Fragment (2a)). The client’s turns are littered with interactional indications of resistance as well: delaying devices such as elongated ‘u:::m’s, intra-turn pauses, cut-offs, and re-starts. Again, in this example, the client leaves without hearing aids or without taking up any other hearing rehabilitation.

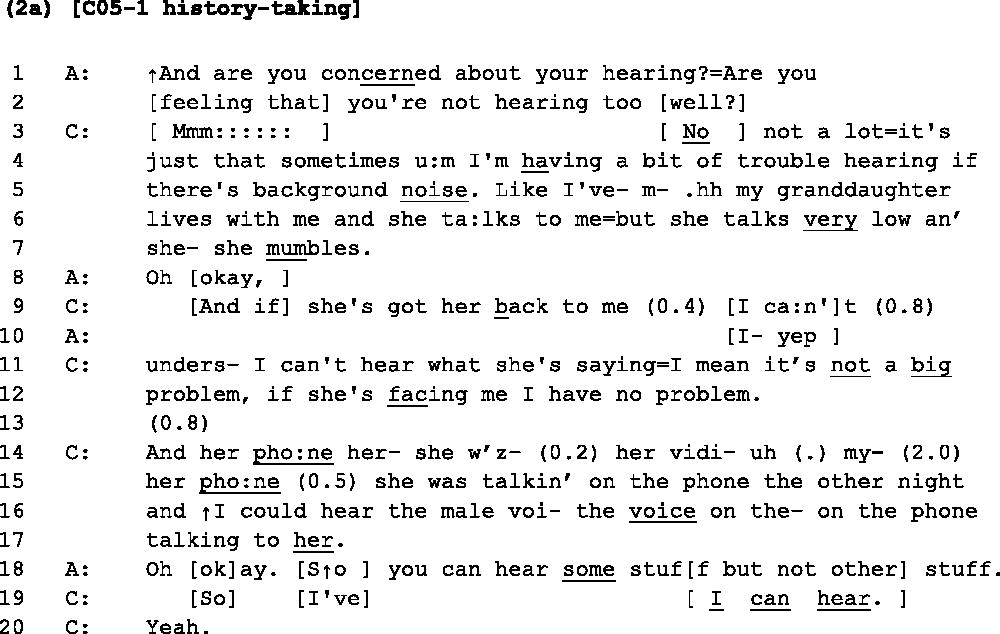

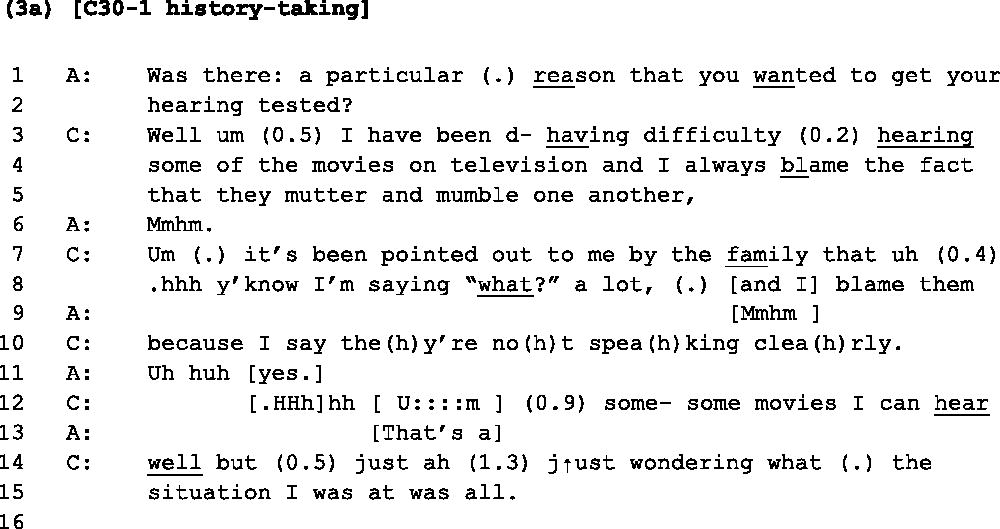

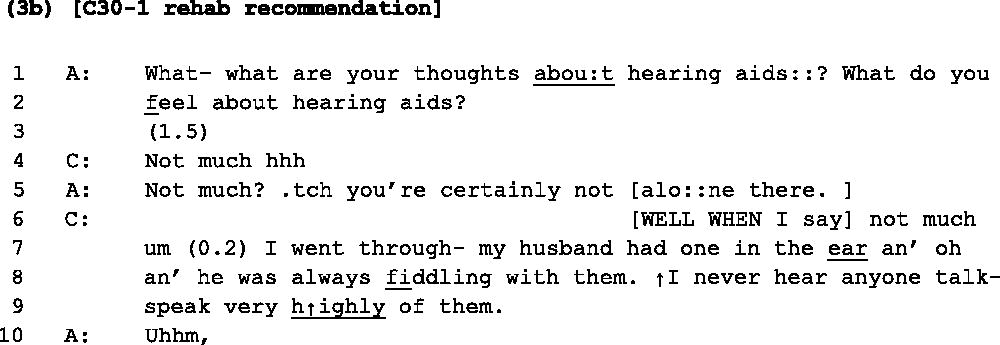

Fragments (3a) and (3b) provide another example of a client displaying an awareness of some possible hearing difficulties but playing them down and attributing blame to others for the difficulties they tend to experience.

In Fragment (3a), the client’s account of her hearing difficulties here is similar to the one seen in Fragment (2a). In response to the audiologist’s history-taking question (lines 1–2), the client provides one situation in which she is having difficulty - hearing movies on the TV. Her turn has markers of a dispreferred response, however. She begins her turn with ‘well’, followed by an ‘um’, and an intra-turn pause, which all act to delay her response (Pomerantz, Citation1984). She then follows this admission by stating that she typically blames her troubles on the actors muttering and mumbling. She continues to explain that her family members point out her hearing difficulties, but again she feels they are not speaking clearly (lines 7–10). In a similar way to Fragment (2a), the client authenticates her account that her difficulties are due to people mumbling by proclaiming that there are some movies she ‘can hear well’ (lines 12 and 14). So again, here we can see the client attributing her hearing difficulties to a particular situation and blaming third parties for her troubles. The client’s account here thus suggests she may still be at the pre-contemplation stage-of-change. And again, in this appointment, the client’s attitude towards her hearing has consequences for how she responds to a recommendation for hearing aids. Fragment (3b) occurs after testing and a diagnosis of mild-moderate hearing loss.

At lines 1–2 of Fragment (3b), the audiologist asks the client how she feels about hearing aids. After a lengthy 1.5 second gap in the interaction, the client responds ‘not much’ followed by a sigh (line 4). Both the content and the construction of her turn indicate resistance to the recommendation. She then goes on to account for her resistance towards them with a recollection that her husband always fiddled with his, and she’d not heard anyone speak highly of their benefits. In this appointment, after further discussion about hearing aids and further resistance from the client, she agrees to go away and think about hearing aids but does not commit to any hearing rehabilitation at this stage.

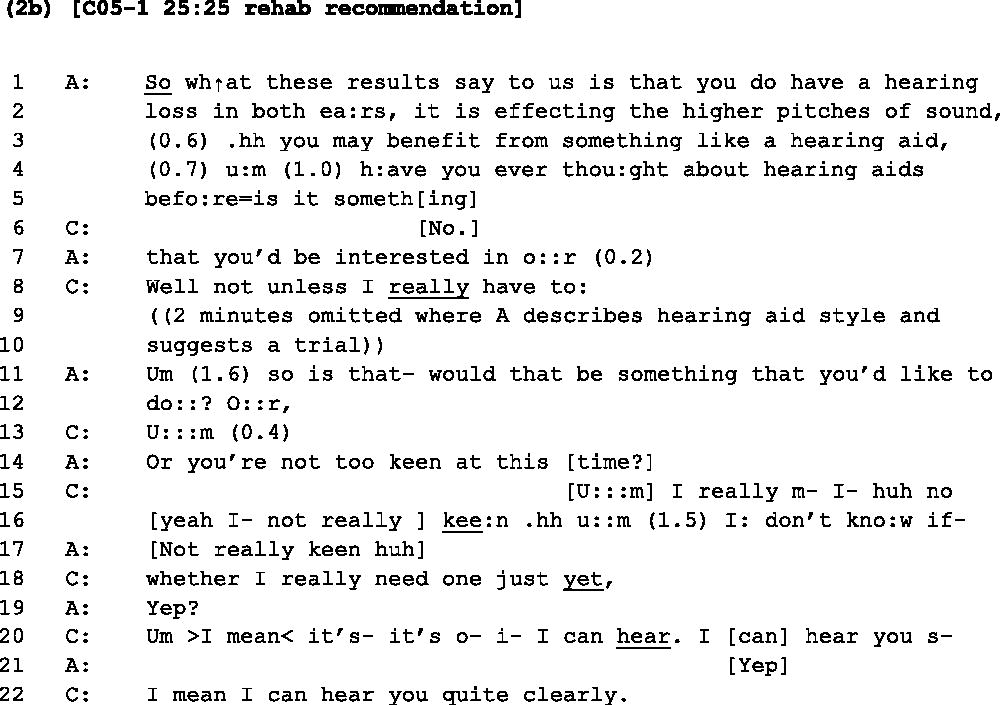

Client displays ‘contemplation for change’

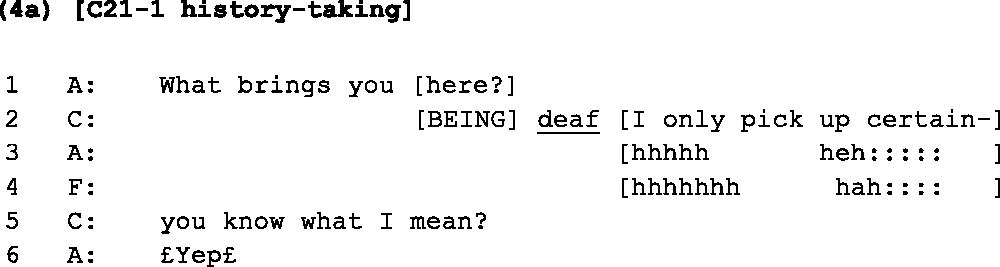

Fragment (4a) provides an example of a client displaying awareness of her hearing loss:

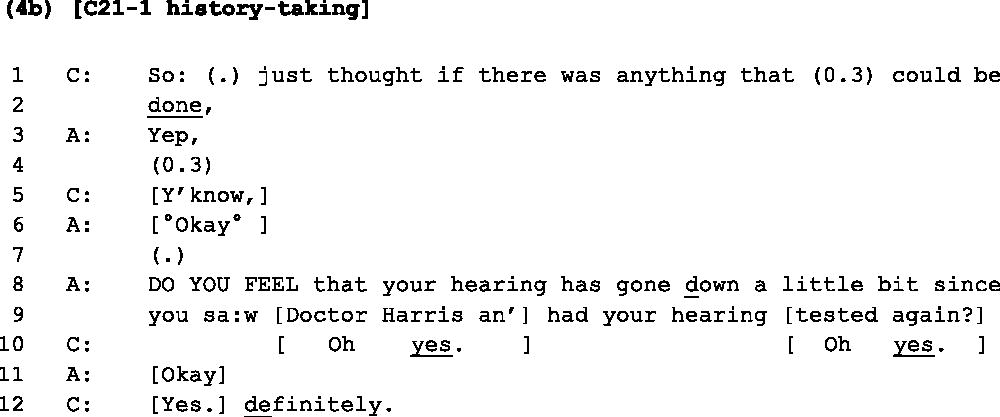

The audiologist delivers an opening question to the client, asking what has brought her into the clinic (line 1). The client makes an explicit disclosure of ‘being deaf’ (line 2). In this opening sequence, the client, therefore, appears to be aware of her hearing difficulties, and attributes the problem to her own hearing rather than any environmental factors. Following Fragment (4a), the client provides some details of the difficulties she is having, including with hearing the TV and hearing people when they are not looking at her. Fragment (4b) occurs 2 minutes later:

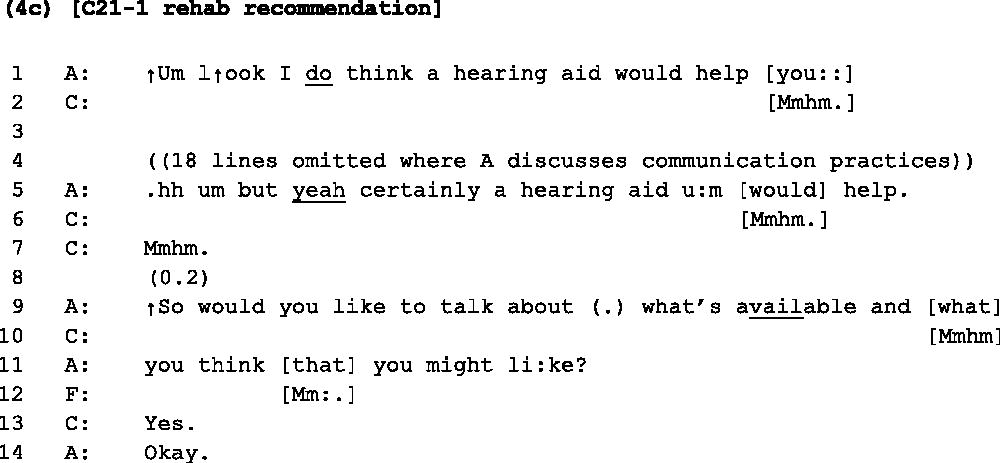

Here, at lines 1–2, the client concludes that she has attended the appointment to see if anything can be done about her hearing. She also reasserts her awareness of her hearing loss at lines 10 and 12, with emphatic ‘Oh yes’ and ‘Yes definitely’ responses to the audiologist. Within this opening history-taking sequence, the client has thus indicated that she is: (1) aware of her problems with hearing; and (2) open to exploring what options might be available to help her hearing. The interaction here suggests that the client would be at the contemplation stage-of-change. She does not mention an explicit intention to go ahead with hearing rehabilitation in the appointment (suggesting she is not quite yet in the preparation stage), but does display a desire to explore ‘whether anything can be done’. The opening interaction thus suggests that she would be open to being offered hearing rehabilitation options if her tests showed that she did indeed have hearing loss. Fragment (4c), below, follows the client’s testing and diagnosis of mild-moderate hearing loss, with the audiologist making a recommendation for hearing aids:

Across the audiologist’s recommendation for hearing aids, the client provides ongoing acknowledgements (‘mmhm’). Then, in response to the audiologist’s question about whether she would like to talk further about the types of hearing aids available, the client provides a clear ‘Yes’ response (line 13). Following this sequence, the interaction progresses into the discussion about hearing-aid options, and the client leaves the appointment having ordered two hearing aids and booking her fitting appointment. These three fragments provide an example of a client who has displayed, within her interaction with the audiologist, both an awareness of her hearing difficulties and an openness to explore options for change, who then takes action toward hearing rehabilitation within the appointment.

Client displays ‘preparation for change’

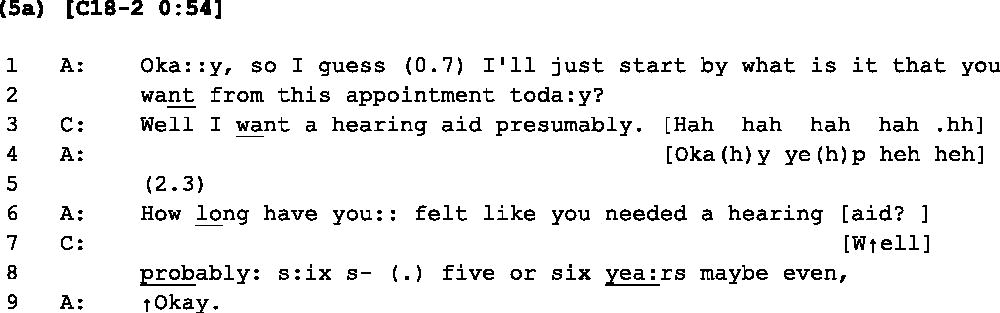

Clients identified in the preparation stage-of-change displayed an explicit intention to take action towards hearing rehabilitation within the history-taking phase of the appointment. Fragment (5a) provides an example:

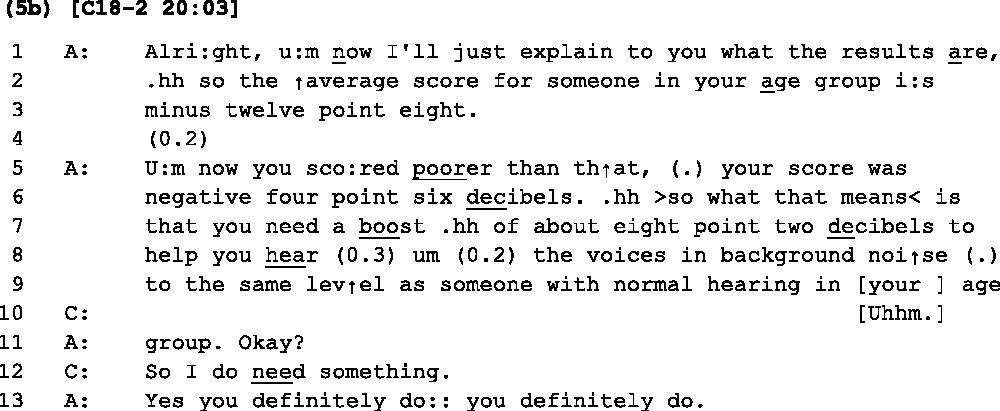

In response to the audiologist’s initial history-taking question (lines 1–2), the client explicitly orients to an intention to take action toward hearing rehabilitation, in this case obtain hearing aids (line 3). She also expresses that she has been aware of hearing difficulties for a long period (‘five to six years’, lines 8). The client’s responses to these two questions suggest that she would be in the ‘preparation’ stage-of-change, and would, therefore, be open to being offered hearing rehabilitation options if diagnosed with a hearing loss. Analysis of the ‘management’ phase of this appointment can shed light on whether this was the case. Fragment (5b) occurs after the completion of audiometric testing where the client is diagnosed with a mild hearing loss:

The audiologist provides an explanation of the client’s hearing loss across lines 1–11. Rather than just acknowledging the diagnosis in response, the client provides an assessment that she must, therefore, need some kind of hearing rehabilitation. The client thus displays her readiness to take action by initiating a discussion about rehabilitation before the audiologist has even made a recommendation. The interaction progresses to a discussion about hearing options for the client, and the client chooses to obtain hearing aids within the appointment. Fragment (5b) thus provides an example of a client who displayed an intention to take action toward hearing rehabilitation in the history-taking phase, and subsequently made the decision to obtain hearing aids in the management phase of the appointment.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that a client’s readiness for hearing rehabilitation is an important aspect for consideration during initial audiology appointments (Babeu et al, Citation2004; Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2013, Citation2015). However, testing clients’ stage-of-change in time-pressured appointments may not always be achievable (Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2013). Analysis of these videoed appointments has demonstrated how clients’ stage-of-change can be observed through their responses to history-taking questions within the initial minutes of the appointment.

Application of the TTM to audiologist-client interactions

The audiology appointments in this study were the first time that rehabilitation options had been discussed between the audiologist and adult client; that is, clients were yet to take any overt or recent action towards hearing rehabilitation prior to the appointment. As the action stage-of-change typically refers to the point where overt behaviour modification occurs, all of the clients were thus identified as being in one of the first three stages-of-change at the beginning of the appointment: pre-contemplation; contemplation; or preparation. Within the corpus, a small number of clients displayed an explicit intention to take action toward hearing rehabilitation within the history-taking phase. These clients could be identified as being in the preparation stage-of-change (this intention to take action at the beginning of the appointment is distinguished from the actual commitment to order hearing aids at the end of the appointment, hence clients being categorized as in ‘preparation’ at this point, rather than ‘action’). Other clients displayed an awareness of their hearing difficulties, and attributed these problems as being due to a decline in their own hearing. These clients could be identified as being at the contemplation stage-of-change. Another group of clients tended to deny or minimize their problems, displayed low concern, and attributed any difficulties they were having to third parties or environmental factors. The way these clients described their hearing loss was indicative of the pre-contemplation stage-of-change. Systematic analysis of the corpus showed that clients’ displayed attitudes toward their hearing (observed during history-taking) have consequences for how they respond to rehabilitation recommendations in the management phase of the appointments. In particular, it appears that the recommendation of hearing aids to clients in the pre-contemplation stage is likely to be received with resistance. This was the case even when clients were eligible for fully-subsidized, Government-funded devices. On the other hand, those clients identified as being in the contemplation or preparation stages-of-change were much more likely to transition to the action stage by the end of the appointment and commit to obtaining hearing aids.

Practical implications for identifying clients’ stage-of-change during history-taking

Based on the findings from this study, there are some key features of clients’ talk that can indicate that they are still in a pre-contemplation stage-of-change in regards to hearing rehabilitation. In particular, the client may:

play down the impact of their hearing difficulties on their everyday life;

display low concern for their hearing difficulties;

provide self-initiated examples of situations where they can hear well;

attribute blame for hearing difficulties to third parties (e.g. family members mumbling, or speaking softly), or situational factors (e.g. background noise);

utilize interactional devices for displaying a dispreferred response when responding to history-taking questions, including delaying devices (e.g. ‘um’, turn-initial ‘well’, intra-turn pauses, cut-offs, and re-starts).

The results from this study emphasize the importance of audiologists building a full and complete history with their clients. As described by Grenness et al, (Citation2015b), many audiologists commonly commence the history with a closed-ended question, interrupt clients’ response and give few opportunities for clients’ to lead the direction of the discussion. This history-taking strategy is unlikely to reveal clients’ stage-of-change to the audiologist. Thus, an opportunity is missed for the audiologist to tailor their management to the client’s individual needs. Audiologists may be able to more readily identify a client’s readiness for change by using open history-taking questions that allow the client to describe their hearing difficulties in their own words. An open history-taking style is also in line with principles of patient-centred care (Grenness et al, Citation2014a,Citationb).

Clinical implications for optimizing clients’ hearing rehabilitation

The findings also suggest that, for clients who appear to be in the pre-contemplation stage-of-change, it may not be the most effective strategy for audiologists to immediately progress to a recommendation of hearing aids. Clients in a pre-contemplation stage-of-change overwhelmingly resisted a recommendation of hearing aids. The TTM describes the ‘processes of change’ that people engage in to progress through the stages of change. The model suggests that, for clients at the pre-contemplation stage-of-change, health practitioners should focus on making changes to how the individual thinks and feels about the health behaviour (i.e. cognitive-affective processes) (Babeu et al, Citation2004). Thus, in order for these clients to take steps toward hearing rehabilitation, it might be more effective for the audiologist to be more flexible in the management phase of the appointment, and focus more broadly on awareness-raising and broader discussions about age-related hearing loss and other forms of communication assistance. Further, it may be particularly important to individualize information provision for these clients (Grenness et al, Citation2014a). Along similar lines, self-determination theory (SDT) would suggest that clients are more likely to adopt and adhere to new health treatments if they have a sense of autonomous motivation to do so (Ng et al, Citation2012; Ryan et al, Citation2008). In support of this theory, a recent study found that autonomous motivation was associated with hearing-aid adoption (Ridgway et al, Citation2015). Clinicians can facilitate client autonomy by providing relevant information and meaningful rationales for change, without applying external pressures that detract from a sense of client choice and agency (Ryan et al, Citation2008). This means that clinicians are encouraged to support clients as they explore resistances and barriers to change.

The use of a decision aid (see Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2010a) can be beneficial for further exploring clients’ feelings about different rehabilitation options, including pursuing no intervention, and thus help audiologists to tailor interventions to suit clients’ degree of readiness for change. These clients may value being offered a choice of rehabilitation options, including participating in individual or group communication programs (Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2012). Motivation tools such as those developed by the Ida Institute may also help clients to reflect on their degree of readiness for change (Clark, Citation2010). Clients who feel pressured or distrustful of the audiologist’s agenda within an appointment may be hesitant to return in the future (Grenness et al, Citation2014a). They would also be unlikely to recommend audiologists to others in their network. On the other hand, taking a patient-centred approach with these clients may facilitate the building of a long-term relationship with their audiologist, and clients may be more willing to return for rehabilitation when they are ready to take that step. If clients do commit to hearing aids when they are ready and motivated to help their hearing, they are more likely to utilize them and fully integrate their hearing rehabilitation into their life (Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2012).

In addition, the presence of a family member may be helpful in these appointments to facilitate a broader discussion of the client’s potential hearing difficulties in everyday life. In many of these appointments, clients reported that family members had concerns about their hearing, even when they did not have concerns themselves. Having a family member in attendance may help audiologists to explicate communication problems within the family. Previous research has found that family members who attend appointments display a desire to have an active involvement in the interaction (Ekberg et al, Citation2014b, Citation2015; Meyer et al, Citation2015; Preminger, Citation2003).

The findings from this study also show support for optimizing communication and counselling education in audiology training. Teaching students how to build a history with the client, and to be more aware of clients’ responses to history questions in the initial stage of the appointment may help them better tailor rehabilitation recommendations for clients, increase clinical efficiency, and increase long-term adherence to their rehabilitation goals. While little published literature explores current practice in teaching communication and patient-centred practice, academics have flagged that such skills are either taught via the hidden curriculum, or are poorly represented relative to other audiology topics in postgraduate degrees (Atkins, Citation2007; English et al, Citation2007). Despite this, the expectation that audiologists possess mastery of counselling skills is observed in Scope Of Practice documents found in many countries (e.g. AAA, Citation2004; ASHA, Citation2006; Audiology Australia, Citation2013; BSA, Citation2012). Much can be learnt by exploring recent developments and empirical findings relating to teaching quality patient-practitioner communication in medical training and other allied health degrees (Hatem et al, Citation2007; Kalet et al, Citation2004).

A limitation of this study was that, within the corpus, there were no examples of audiologists using an awareness-raising approach with clients identified as being at a pre-contemplation stage-of-change. Future research might examine how clients respond to such approaches, and whether this can better help clients progress towards some kind of hearing rehabilitation. Future research may also seek to directly compare clients’ responses to history-taking questions during the appointment, with their responses on questionnaires such as the URICA and the Ida Institute motivation tools. Limitations of the TTM have been documented, and the validity of the model has been questioned by some researchers (e.g. Bridle et al, Citation2005). Some of the previous studies investigating the TTM have been methodologically weak, and there have been ambiguous results relating to its effectiveness. It has been suggested that the model needs further specification of which, and how, different processes relate to particular stages of change (Bridle et al, Citation2005). However recent studies conducted in audiology, particularly focussing on stages-of-change, have demonstrated support for the use of this model (e.g. Laplante-Lévesque et al, Citation2010b, Citation2012; Citation2013, Citation2015).

Conclusion

Clients’ readiness for hearing rehabilitation can be observed within their responses to history-taking questions in initial audiology appointments. Clients’ stage-of-change can have important consequences for how they respond to a recommendation of hearing aids in the management phase of the appointment. In particular, clients who appear to be in a pre-contemplation stage-of-change tended to resist a recommendation of hearing aids. The transtheoretical model of behaviour change can be useful for helping audiologists fit a rehabilitation plan to individual clients based on their needs, attitudes, desires, and psychological readiness for action.

| Abbreviations | ||

| URICA | = | University of Rhode Island Change Assessment |

| CA | = | Conversation analysis |

| HI | = | Hearing impairment |

| SDT | = | Self-determination theory |

| TTM | = | Transtheoretical model of behaviour change |

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted under the HEARing Cooperative Research Centre, established and supported under the Cooperative Research Centres Program, an initiative of the Australian Government.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- AAA. 2004. Audiology: Scope of practice. American Academy of Audiology.

- ASHA. 2006. Counseling preferred practice patterns for the profession of audiology. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

- Atkins C. 2007. Graduate slp/aud clinicians on counseling: Self-perceptions and awareness of boundaries. Contemp Issues Commun Sci Disord, 34, 4–11.

- Audiology Australia. 2013 Professional practice standards - part b clinical standards. Audiology Australia (www.audiology.asn.au).

- Babeu L.A., Kricos P.B. & Lesner S.A. 2004. Application of the stages-of-change model in audiology. J Acad Rehabil Audiol, 37, 41–56.

- Bridle C., Riemsma R.P., Pattenden J., Sowden A.J., Mather L. et al. 2005. Systematic review of the effectiveness of health behavior interventions based on the transtheoretical model. Psychol Health, 20, 283–301.

- BSA. 2012 Common principles of rehabilitation for adults with hearing- and/or balance-related problems in routine audiology services. Practice Guidance. Reading: British Society of Audiology.

- Chien W. & Lin F.R. 2012. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med, 172, 292–293.

- Claesen E. & Pryce H. 2012. An exploration of the perspectives of help-seekers prescribed hearing aids. Prim Health Care Res Dev, 13, 279–284.

- Clark, J.G. 2010. The geometry of patient motivation: circles, lines, and boxes. Audiol Today. Reston, VA: American Academy of Audiology, 32–40.

- Drew P., Chatwin J. & Collins S. 2001. Conversation analysis: A method for research into interactions between patients and health-care professionals. Health Expect, 4, 58–70.

- Drew, P. & Heritage, J. 1992 Talk at Work: Interaction in Institutional Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ekberg K., Grenness C. & Hickson L. 2014a. Addressing patients’ psychosocial concerns regarding hearing aids within audiology appointments for older adults. Am J Audiol, 23, 337–350.

- Ekberg K., Meyer C., Scarinci N., Grenness C. & Hickson L. 2014b. Disagreements between clients and family members regarding clients’ hearing and rehabilitation within audiology appointments for older adults. J Interact Res Commun Disord, 5, 217–244.

- Ekberg K., Meyer C., Scarinci N., Grenness C. & Hickson L. 2015. Family member involvement in audiology appointments with older people with hearing impairment. Int J Audiol, 54, 70–76.

- English K., Naeve-Velguth S., Rall E., Uyehara-Isono J. & Pittman A. 2007. Development of an instrument to evaluate audiologic counseling skills. J Am Acad Audiol, 18, 675–687.

- Gopinath B., Schneider J., Hartley D., Teber E., McMahon C.M. et al. 2011. Incidence and predictors of hearing aid use and ownership among older adults with hearing loss. Ann Epidemiol, 21, 497–506.

- Grenness, C., Hickson, L., Laplante-Lévesque, A. & Davidson, B. 2014a. Patient-centred audiological rehabilitation: Perspectives of older adults who own hearing aids. Int J Audiol, 53, S68–S75.

- Grenness, C., Hickson, L., Laplante-Lévesque, A. & Davidson, B. 2014b. Patient-centred care: A review for rehabilitative audiologists. Int J Audiol, 53, S60–S67.

- Grenness C., Hickson L., Laplante-Lévesque A., Meyer C. & Davidson B. 2015a. The nature of communication throughout diagnosis and management planning in initial audiologic rehabilitation consultations. J Am Acad Audiol, 26, 36–50.

- Grenness C., Hickson L., Laplante-Lévesque A., Meyer C. & Davidson B. 2015b. Communication patterns in audiologic rehabilitation history-taking: audiologists, patients, and their companions. . Ear Hear, 36, 191–204.

- Hall K.L. & Rossi J.S. 2008. Meta-analytic examination of the strong and weak principles across 48 health behaviors. Prev Med, 46, 266–274.

- Hartley D., Rochtchina E., Newall P., Golding M. & Mitchell P. 2010. Use of hearing aids and assistive listening devices in an older Australian population. J Am Acad Audiol, 21, 642–653.

- Hatem D.S., Barrett S.V., Hewson M., Steele D., Purwono U. et al. 2007. Teaching the medical interview: Methods and key learning issues in a faculty development course. J Gen Intern Med, 22, 1718–1724.

- Heritage J. & Maynard D.W. 2006 Communication in Medical Care: Interaction between Primary Care, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. & Raymond, G. 2010 Navigating epistemic landscapes: Acquiescence, agency and resistance in responses to polar questions. deRuiter J-P (ed.), Questions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jefferson, G. 2004. Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. Lerner G (ed.), Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 13–23.

- Kalet A., Pugnaire M.P., Cole-Kelly K., Janicik R., Ferrara E. et al. 2004. Teaching communication in clinical clerkships: Models from the macy initiative in health communications. Acad Med, 79, 511–520.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Brännström K.J., Ingo E., Andersson G. & Lunner T. 2015. Stages of change in adults who have failed an online hearing screening. Ear Hear, 36, 92–101.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2010a. A qualitative study of shared decision making in rehabilitation audiology. J Acad Rehabil Audiol, 43, 27–43.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2010b. Factors influencing rehabilitation decisions of adults with acquired hearing impairment. Int J Audiol, 49, 497–507.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2012. What makes adults with hearing impairment take up hearing aids or communication programs and achieve successful outcomes? Ear Hear, 33, 79–93.

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Hickson L. & Worrall L. 2013. Stages of change in adults with acquired hearing impairment seeking help for the first time: Application of the transtheoretical model in audiologic rehabilitation. Ear Hear, 34, 447–457.

- Meyer C. & Hickson L. 2012. What factors influence help-seeking for hearing impairment and hearing aid adoption in older adults? Int J Audiol, 51, 66–74.

- Meyer C., Hickson L., Kahn A., Hartley D., Dillon H. et al. 2011. Investigation of the actions taken by adults who failed a telephone-based hearing screen. Ear Hear, 32, 720–731.

- Meyer C., Scarinci N., Ryan B. & Hickson L. 2015. “This is a partnership between all of us”: Audiologists’ perceptions of family member involvement in hearing rehabilitation. Am J Audiol, 24, 536–548

- Milstein D. & Weinstein B.E. 2002. Effects of information sharing on follow-up after hearing screening for older adults. J Acad Rehabil Audiol, 25, 43–58.

- Ng J.Y.Y., Ntoumanis N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani C., Deci E.L., Ryan R.M. et al. 2012. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci, 7, 325–340.

- Pilnick A., Hindmarsh J. & Gill V.T. 2009. Beyond doctor and patient: Developments in the study of healthcare interactions. Sociol Health Illn, 31, 787–802.

- Pomerantz, A. 1984. Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. Atkinson JM and Heritage J (eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 57–101.

- Preminger J. 2003. Should significant others be encouraged to join adult group audiologic rehabilitation classes? J Am Acad Audiol, 14, 545–555.

- Prochaska, J.O., Redding, C. & Evers, K. 2009 The Transtheoretical Model and stages of change. Glanz K, Lewis FM and Rimer BK (eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice Fourth Edition ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications, Inc., 97–122.

- Raymond D.M. & Lusk S.L. 2006. Staging workers’ use of hearing protection devices: Application of the Transtheoretical Model. AAOHN Journal: Official Journal of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses, 54, 165–172.

- Ridgway, J., Hickson, L. & Lind, C. 2015. Autonomous motivation is associated with hearing aid adoption. Int J Audiol, 1–9. Early Online,

- Ryan R.M., Patrick H., Deci E.L. & Williams G.C. 2008. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on Self-Determination Theory. The European Health Psychologist, 10, 2–5.

- van den Brink R.H.S., Wit H.P., Kempen G.I.J.M. & van Heuvelen M.J.G. 1996. Attitude and help-seeking for hearing impairment. Br J Audiol, 30, 313–324.

Appendix 1

Jeffersonian transcription system

This list represents the most widely-used transcription symbols used in this study. For a more comprehensive list, see Jefferson (Citation2004).

Appendix 2