Abstract

This research examined the prevalence of morning symptoms and their relationship with health status, exacerbations and daily activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Data on 1489 patients were analysed from a European and USA sample. Results were tested for significance (p < 0.05) using Mann-Whitney and regression modelling accounting for age, gender, body mass index, comorbidities, symptom severity, smoking status and medication adherence. Morning symptoms were experienced by 39.8% of patients. Controlling for potential confounders, morning symptoms were significantly associated with higher COPD assessment test scores (p < 0.001) and exacerbation frequency (p < 0.001), more frequent worsening of symptoms without consulting a Health Care Professional (p = 0.008), and increased impact on normal daily activities (p = 0.007); and in the working population, a significantly greater impact on getting up and ready for the day (p < 0.001) and significantly more days off work per year (p < 0.001). Our research concluded that in patients with COPD, morning symptoms are associated with poorer health status, impaired daily activities and increased risk of exacerbation in affected patients compared with those patients without morning symptoms. Improved control of patients’ morning symptoms may lead to substantial reduction in COPD impact and frequency of exacerbations, and enable patients to increase daily activities, particularly early morning activities. This could, in turn, enable working patients with COPD to be more productive in the workplace.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of death and disability in both the developed and developing world (Citation1–3). A conservative estimate indicates 210 million people worldwide suffer from the condition (Citation4) and morbidity and mortality are growing (Citation3). If well controlled, COPD can be considered a steadily progressive condition between exacerbations (Citation5).

Historically, the diagnosis of COPD and assessment of severity have been mainly based on the level of airflow limitation. Thus, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (Citation6) originally classified COPD into four groups based on FEV1 (% predicted): mild (I), moderate (II), severe (III), and very severe (IV). However, the need for accurate assessment of symptom levels and exacerbation risk has been subsequently recognised, and a major revision of the GOLD document in 2011 linked holistic evaluation of COPD symptoms, impact, exacerbation frequency and lung function with targeted treatment (Citation7).

The impact of COPD may relate not only to the severity but also to the variability of symptoms, such as cough, sputum production, wheeze and breathlessness, and this variability may contribute to quality of life impairment (Citation5,Citation8). Variation in symptoms can be experienced day and night, weekly or seasonally, but many patients report that the most troublesome symptoms occur at night and on waking (Citation5). Sleep is disturbed and early morning symptoms are reported to affect tasks associated with getting up and getting ready for work (Citation8). They may continue to affect patients’ activities throughout the day, at home and at work. However, studies of daily and long-term effects of symptom variability and, more specifically, of the presence of early morning symptoms, and the identification of affected populations are limited. Thus, there is need for ongoing real-world data to provide a holistic picture of this condition.

The objective of this analysis of our real-world dataset was to ascertain the proportion of patients with symptom variability, specifically morning symptoms, and the type and range of those symptoms. It also sought to assess the relationship between morning symptoms and other markers of the impact of COPD, such as exacerbations, health status, attendance and non-attendance at work.

Methods

Research design

The data for these analyses were drawn from the Adelphi Respiratory Disease Specific Programme (DSP). DSPs are large, multinational, cross-sectional surveys, which collect representative clinical real-world data from physicians and outpatient populations. They provide an established method for investigating multicentre patient characteristics and treatment practices for a range of common chronic diseases. The full methodology has been published previously (Citation9).

Data were collected between June and September 2011 in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom and the United States. Physicians were identified from public lists of healthcare professionals by local fieldworkers according to predefined selection criteria, as detailed below, to ensure the sample was representative of COPD management in each participating country. Following telephone screening, participating physicians (primary and secondary care) completed a patient record form (PRF) for consecutive prospective consulting patients with COPD. The same patients then voluntarily and independently filled out a patient self-completion form (PSC). At no stage did the physician see or influence patient responses. Identification numbers allowed patient data to be linked with corresponding data recorded by the physician. All diagnostic assessments and treatment choices were at the discretion of the physician. No tests or investigations were performed as part of this research. Data were collected by local fieldwork partners and both doctor and patient data were de-identified prior to receipt by Adelphi.

The survey adhered to the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association guidelines (Citation10). The Code of Conduct states that ethical approval is not necessary for surveys of this nature, as the purpose of the research is to improve understanding and not to test any hypotheses, subject to research being conducted in full accordance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 (Citation11) and European equivalents (Citation10).

Physician and patient recruitment criteria

Physicians had to be qualified for more than 5 years and less than 36 years and see ≥3 patients with COPD per week. These physicians contributed to the research on a voluntary basis. Participating patients were the next 6 consulting patients ≥40 years of age with a history of smoking, diagnosed with airflow obstruction and COPD, irrespective of the reason for consultation with the physician that day. Patients with a diagnosis of asthma were excluded. Only patients with complete data for age, gender, BMI, physician-assessed reports of severity and adherence to medication, smoking status, co-morbidities and current treatment were included in the analyses.

Recorded variables

Physician-completed PRFs included demographic information, smoking status, physician-assessed severity grade, FEV1% predicted, time since diagnosis, comorbidities, current treatment regimen and treatment adherence of all patients. Symptoms over the previous 4 weeks and their impact on daily life were reported in detail by the physician in the PRF, recording the exact nature, timing, frequency and severity of symptoms: shortness of breath (SOB) when resting, when exercising and when exposed to triggers, bronchospasm, chest tightness, cough, excess sputum production, and wheezing. In the current research, morning symptoms were defined as those present when getting up in the morning, thus those symptoms present on waking, rather than those persisting through the morning.

To assess disease impact, patients were asked to estimate on a seven-point Likert scale—with a range of no impact to constant impact—what effect symptoms had on sleep and on daily life, including getting up and ready for the day, normal daily activities, mood, personal relationships, leisure and work activities. Physicians also recorded the frequency of exacerbations in the last 12 months. For the purposes of this research, exacerbations were physician-defined relating to an increase in symptoms not brought under control by a patient's rescue medication and therefore requiring further intervention.

Clinical and patient reported outcomes

Additional information collected from both physicians and patients was used as a measure of disease burden associated with morning symptoms. PSC forms recorded data on (i) patient-rated impact on work, normal daily activities, and getting up and ready for the day, (ii) frequency of increase in symptoms without the intervention of a Health Care Professional (HCP), (iii) rescue inhaler usage in the last 4 weeks, (iv) number of days off work in the last 12 months, (v) EuroQoL-5 dimensions (EQ-5D) utility index (Citation12) and (vi) COPD Assessment Test (CAT) (Citation13).

Statistical analysis

Statistics first described numbers of participating primary and secondary care physicians, numbers of physician- and patient-completed forms per country, general patient characteristics, the proportion of patients experiencing morning symptoms and their type and range, and treatment regimens. Univariate analysis compared those with and without morning symptoms. Patients qualifying as “with morning symptoms” were those reporting, in the previous 4 weeks, one or more symptoms experienced specifically when getting up in the morning. Univariate analyses examined the relationship between morning symptoms and the following variables: age, gender, BMI, smoking status, most recent FEV1% predicted, time since diagnosis and treatment. Statistical differences between groups were assessed using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and unpaired t-tests or Mann−Whitney tests for continuous variables depending on their distribution.

Multivariate modelling methods, including negative binomial regression, logistic regression, and ordinary least squares regression, were applied to the same set of outcome variables to adjust for confounding factors. A first multivariate analysis was designed to examine the relationship between patients’ characteristics and morning symptoms. Another multivariate regression analysis was then performed to assess the relationship between markers of COPD impact and morning symptoms. In these analyses, the following potential confounders were accounted for: age, gender, BMI, smoking status, physician-subjective severity evaluation of COPD condition, current maintenance regimen, physician-reported treatment adherence, serious comorbid cardiovascular disease (e.g. angina, coronary arterial disease), physician-confirmed diagnosis of depression and sleep apnoea. Confounder selection was based on knowledge of the disease and included a range of patient and disease characteristics; selection was not limited to variables significantly associated with morning symptoms. Further specific analyses were also conducted in the subset of patients who were still working. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE software version 12.1 (Citation14).

Results

Physician and patient population

Records were provided by 639 participating physicians for a total of 3813 patients consulting with a diagnosis of COPD. Matched physician and patient forms were available for 2408 of those patients, and a final 1489 (61.8%) had complete data for all confounders and clinical and patient reported outcomes. Most patients had mild-to-moderate severity of airflow obstruction. At the time the research was conducted, 440 patients (29.6%) were still in paid employment.

General symptoms and variability

Physicians reported a mean of 592 patients (39.8%) experiencing morning symptoms (), with some variability of the predominant symptom type. The two most common morning symptoms were cough (27%) and excess sputum production (21%). Other early morning symptoms were: SOB when exercising (9%), wheezing (8%), SOB when resting (6%), chest tightness (6%), bronchospasm (5%), and SOB when exposed to a trigger (2%).

Table 1. Physician specialty, country and distribution of morning symptoms (1489 patients)

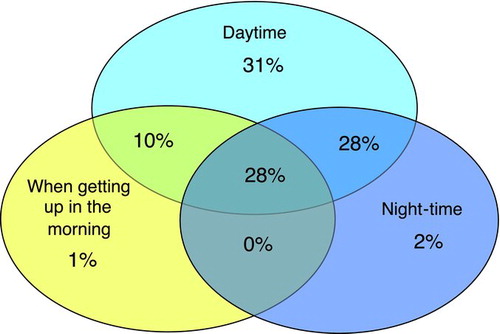

Very few patients experienced morning symptoms in isolation (1%). Over half of patients (56%) were reported by physicians to have symptoms persisting both day and night, with virtually all patients (97%) reporting symptoms during the day compared with the night (58%) ().

The most common symptom reported during the day was SOB when exercising (74.1%) followed closely by cough (71.8%). Further analysis using multivariate modelling, and adjusting for potential confounders, showed morning symptoms in patients with COPD significantly associated with current smoking (p = 0.022), with more severely affected patients as subjectively reported by the physician (p < 0.001), with physician-confirmed diagnosis of depression (p = 0.021), and physician-reported treatment adherence (p = 0.021).

General characteristics of patients with and without morning symptoms: univariate analyses

Univariate analyses showed patients with morning symptoms were significantly older, had worse lung -function and had been diagnosed for longer. The gender distribution was similar between those with and those without morning symptoms ().

Table 2. Patient characteristics for total cohort and patients without/with morning symptoms (1489 patients unless otherwise stated)

Patient's adherence to treatment regimens as assessed by physicians, on a scale of 1 (not adherent) to 5 (totally adherent), showed significant differences between those with morning symptoms (3.97) and those without (4.13). Patients with morning symptoms took a higher number of maintenance treatments and were more frequently receiving inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), 64.8%, with 56.3% patients on an ICS + long acting beta2 agonist fixed dose combination (ICS/LABA FDC). Thus, they were less likely to receive maintenance therapy with long-acting bronchodilators only. There was no significant difference between patients who experienced morning symptoms and those who did not in terms of gender, BMI and frequency of associated depression, cardiovascular co-morbidities or sleep apnoea ().

Relationship between morning symptoms and measures of COPD impact

Patients experiencing morning symptoms, compared with those without morning symptoms, had significantly higher CAT scores and lower EQ-5D scores, indicative of greater impact of symptoms and poorer health status. They also experienced significantly more exacerbations over the previous 12 months, reported more frequent usage of rescue inhaler and a higher number of times that their symptoms worsened without requiring to visit an HCP. Impact on normal daily activities, measured on a 7-point Likert scale of no impact to constant impact, where 7 represents constant impact, was also significantly higher in those with morning symptoms compared with those without, 3.96 versus 3.29, respectively ().

Table 3. Association between morning symptoms and measures of COPD impact: (A) univariate analysis and (B) multivariate analysis controlling for potential confounders (1489 patients)

When controlling for potential confounders, patients experiencing morning symptoms were still characterised by significantly higher CAT scores, higher exacerbation frequency, more frequent worsening of symptoms without seeing an HCP and increased impact on normal daily activities. However, patients with morning symptoms were no longer significantly associated with higher rescue inhaler usage and lower EQ-5D utility score ().

Relationship between morning symptoms and employment related outcomes

For patients in paid employment at the time of the research, univariate analysis revealed that the -disease's impact on getting up and ready for the day was -significantly higher in those with morning symptoms. Working patients with morning symptoms reported a significantly higher impact during the working day, measured on a 7-point Likert scale, than those -without morning symptoms. They also took significantly more days off work in the previous 12 months ().

Table 4. Association between morning symptoms and employment related measures of COPD impact: univariate analyses (440 patients)

When potential confounding factors were taken into consideration, these results remained significant regarding the impact on getting up and ready for the day and on the number of days taken off work in 12 months. However, the impact of morning symptoms whilst at work was no longer significant ().

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of the 2011 Respiratory DSP real-world data on consulting patients with COPD found that almost 40% of our COPD patient sample was reported to have morning symptoms. These were not generally experienced in isolation, but were part of an ongoing variability of daily symptoms.

Patients experiencing morning symptoms were significantly older, were more likely to be current smokers, had worse lung function, had been diagnosed for longer, and had received more maintenance treatments. Multivariate modelling data indicated a significant association between morning symptoms and being a current smoker, and with physician-assessed severity, depression and treatment adherence. With cigarette smoke being the main cause of chronic airways inflammation in smokers (Citation15), the increased rate of sputum production and coughing in these patients will likely contribute to morning symptoms. Poor adherence to treatment and greater disease severity may explain the general presence of more symptoms, in particular morning -symptoms. This, coupled with depression, which in those with COPD is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality (Citation16), may indicate why CAT scores were significantly higher for these patients, with an overall greater impact of their COPD. Accordingly, the impact of COPD on their daily life was more pronounced and their quality of life, as measured by EQ-5D, was -significantly poorer. Therefore it is perhaps unsurprising that those with morning symptoms reported significantly more frequent rescue inhaler usage and worsening of symptoms, without HCP intervention, as well as significantly more exacerbations.

When multivariate analysis was performed with all “impact variables,” all but EQ-5D utility score and rescue inhaler usage remained independently associated with morning symptoms. CAT and EQ-5D are both measures of health status. Therefore they are in part redundant, which explains why only one of them remained independently associated with symptoms in the multivariate model. Since CAT is more COPD-specific, it could be anticipated that it would be more strongly associated with COPD symptoms than the EQ-5D. Similarly, worsening of symptoms and usage of rescue medications are also redundant, so that only one remains in the multivariate model. For those patients, getting up and ready for the day and numbers of days taken off work in a 12-month period were more strongly associated with morning symptoms than the day at work, which was certainly in part redundant with one or both of these two variables.

Two other studies have examined the impact of morning symptoms and/or symptom variability in patients with COPD and although the foci of these two studies were different to the current one, conclusions on diurnal symptom differences and symptom variability, and the impact of morning symptoms in particular were largely in agreement. All were cross-sectional, but data were collected differently and patient criteria varied. As in the current research, the physicians in the work by Kessler et al. (Citation5) completed the equivalent of a Patient Record Form for each patient. However, patients’ subjective information was collected via telephone by professional interviewers. In the study conducted by Partridge et al. (Citation8) only patient data were collected and via quantitative Internet interviews.

While the current research focussed specifically on morning symptoms and their impact on daytime activities, Kessler et al. (Citation5) looked more generally at the detail of symptom variability, specifically diurnal variability, including night-time symptoms and sleep disturbance, as well as weekly, annual and seasonal differences. Partridge et al. (Citation8) also examined diurnal variations in symptoms, and looked specifically at morning symptoms and their impact. Both our survey and that of Partridge indicated excess phlegm and cough as the most troublesome symptoms first thing in the morning. However, consistent with both Kessler et al., (Citation5) where 72.5% of patients reported dyspnoea throughout the day, (Citation5) and Partridge et al. (Citation8), who reported SOB as the most frequently reported symptom amongst patients with COPD, the current research reported shortness of breath when exercising (74.1%) followed closely by cough (71.8%) as the most common symptoms during the rest of the day. These results may reflect the difference in symptoms immediately on awakening as reported in our survey compared with symptoms that develop and persist throughout the morning period and the rest of the day.

Nearly two-thirds of the patients experiencing morning symptoms in the current survey were receiving an ICS (64.8%), most commonly in the form of an ICS/LABA FDC (56.3%). Interestingly, Kessler et al observed that approximately half of all patients made no changes to the way they used their medication when symptoms became more bothersome (Citation5). They suggested that patients with COPD take their combination regimens too late after waking up to fully benefit from their therapeutic effects. This hypothesis is supported by the findings of Partridge et al. (Citation17) when comparing two effective COPD maintenance regimens; in the Partridge study, the maintenance combination of budesonide and formoterol, by its more rapid onset of action when compared with a salmeterol/fluticasone combination, enabled patients to perform early morning activities with greater ease.

Recent research looking at employment in patients with chronic lung disease, including COPD, was conducted by Fletcher et al. in 2011 in Europe, Brazil, China, Turkey and the USA (Citation2). These authors specifically examined the impact of COPD on working patients and the economic impact on patients, healthcare systems and society in general. Twenty-six percent of unemployed respondents, with a mean age of 58.3 years [range 45–67 years], had given up work because of their COPD. The authors concluded that COPD had a marked effect on the working population at a cost to society that was greater than previously recognised, and that more optimal timing of patient-focused treatment was necessary to deal with specific symptom characteristics.

In that respect, long-acting bronchodilators taken twice daily (e.g. aclidinium) (Citation18) or with faster onset of action (i.e. indacaterol or glycopyrronium) (Citation19–21) might be of interest to prevent, limit or relieve morning symptoms and their consequences on daily activity. Specific studies need to be conducted to assess whether they provide a clinically significant advantage in that respect. In addition some recent studies suggest that patients with COPD undertaking pulmonary rehabilitation show improvements across a range of clinical and patient-reported measurements (Citation22,23), although there was no specific evidence to suggest an improvement in symptoms experienced in the morning. Finally, the results presented here suggest that smoking cessation, improved treatment adherence and treatment of depression could help alleviation of morning symptoms.

The methodology of data collection through the DSP has some limitations. Diagnosis of patients within the target group depends very much on the diagnostic skills of the physician rather than any predetermined set of disease parameters enforced by the research protocol. Kessler et al. recognised this problem (Citation5), noting as a weakness the possible inadvertent inclusion of patients with combined diseases that might affect COPD symptom levels. As in the present survey, patients with confirmed asthma were excluded. It is important to recognise that this sample of patients is taken from those consulting their physician in routine care, and this therefore may restrict the generalizability of our findings to that of the whole COPD population. In addition, a limitation may be seen in the absence of a control group with no respiratory disease, but potentially with morning symptoms resulting from acute respiratory conditions such as colds and flu. As for all cross-sectional studies, a primary weakness is the lack of ability to show cause and effect; however, in this analysis potential confounders were introduced to strengthen the validity of the significant associations shown.

Despite these limitations, such real-world data have a great deal to contribute to the understanding of the impact of COPD on the lives of patients, and of patients’ and doctors’ attitudes towards the disease and its -treatment.

In the current work morning symptoms were defined as those present when getting up in the morning, thus those symptoms present on waking, rather than those persisting through the morning. An area of future research might usefully distinguish between the two types and the relative impact on patients’ health status and the rest of their day. In addition, the most common morning symptoms reported here were cough and sputum, which are indicative of a chronic bronchitic phenotype. Interestingly, this phenotype has also been associated with an increased risk of exacerbations (Citation24), as well as with accelerated lung function decline and increased morbidity (Citation25). Thus, any overlap between this phenotype and the putative “morning symptoms phenotype” warrants further research.

In conclusion, morning symptoms are associated with poorer health status, impaired daily activities and increased exacerbation risk in affected patients with COPD compared with those presenting without morning symptoms. Thus, better control of symptoms in the morning could benefit the patient throughout the day, leading to fewer periods of worsening symptoms and, in the longer term, fewer exacerbations. This should be recognised by physicians and used to aid the disease management of stable COPD. Our results would also suggest that in the working population of patients, targeting symptom relief on awakening could lead to fewer days of absence from work.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Maren White of White Quill Ltd.

Declaration of Interest Statement

Apart from Prof. Roche, all mentioned authors are employed by Adelphi Real World. In the past 5 years, Nicolas Roche has received (i) fees for speaking, -organising education, or consulting from Aerocrine, Almirall, Altana Pharma-Nycomed, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, MEDA, MSD-Chibret, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Teva; (ii) research grants from Novartis, Nycomed and -Boehringer Ingelheim.

This analysis was funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Mapel DW, Roberts MH. New clinical insights into chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their implications for pharmacoeconomic analyses. Pharmacoeconomics 2012;Oct 1; 30(10):869–85.

- Fletcher MJ, Upton J, Taylor-Fishwick J, Buist SA, Jenkins C, Hutton J, COPD uncovered: an international survey on the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] on a working age population. BMC Public Health 2011; 11:612.

- Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gillespier S, Burney P, Mannino DM, BOLD Collaborative Research Group. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (The BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007; 370:741–750.

- Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, Badamgarav E, Buist AS, Mannino DM. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta analysis. Eur Respir J 2006; 28(3):523–532.

- Kessler R, Partridge MR, Miravitlles M, Cazzola M, Vogelmeier C, Leynaud D, Ostinelli J. Symptom variability in patients with severe COPD: a pan-European cross-sectional study. Eur Respir J 2011; 37:264–272.

- GOLD PM. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic pulmonary disease, 2001. http://www.goldcopd.org/Guidelines/guidelines-resources.html.

- Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, GOLD Executive Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187 (4):347–365.

- Partridge MR, Karlsson N, Small IR. Patient insight into the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the morning: an internet survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25(8):2043–2048.

- Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-Specific Programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24(11):3063–3072.

- European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR), International Code of Marketing and Social Research Practice 2007, http: //www.icc.se/reklam/english/engresearch.pdf, accessed 22 August 2013.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule Aug 2009, www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/index.html, accessed 22 August 2013.

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psycholpharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321–326.

- Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009 Sep; 34(3):648–654.

- StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

- Damia ADD, Gimeno JC, Ferrer MJs, Fabregas ML, Folch PA, Paya JM. A study of the effect of proinflammatory cytokines on the epithelial cells of smokers, with or without COPD. Arch Bronconeumol 2011; 47(9):447–453.

- Julian LJ, Gregorich SE, Earnest G, Eisner MD, Chen H, Blanc PD, Screening for depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 2009; 6(6):452–458.

- Partridge MR, Schuermann W, Beckman O, Persson T, Polanowski T. Effect on lung function and morning activities of budesonide/formoterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone in patients with COPD. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2009; 3(4):1–11.

- Kerwin EM, D'Urzo AD, Gelb AF, Lakkis H, Gil EG, Caracta CF. Efficacy and safety of a 12-week treatment with twice-daily aclidinium bromide in COPD patients (ACCORD COPD I). COPD 2012; 9:1–12.

- D'Urzo A, Ferguson GT, van Noord JA, Hirata K, Martin C, Horton R, Efficacy and safety of once-daily NVA237 in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD: the GLOW1 trial. Respiratory Res 2011; 12:156–159.

- Kerwin E, Hebert J, Gallagher N, Martin C, Overend T, Alagappan VKT, Lu Y, Banerji D. Efficacy and safety of NVA237 versus placebo and tiotropium in patients with COPD: the GLOW2 study. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1–10.

- Beeh KM, Singh D, Di Scala L, Drollman A. Once-daily NVA237 improves exercise tolerance from the first dose in patients with COPD: the GLOW3 trial. Int J COPD 2012; (7):503–513.

- Liu XL, Tan JY, Wang T, Zhang Q, Zhang M, Mao LQ, Chen JX. Effectiveness of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Rehabil Nurs Epub 2013/06/18.

- Ramponi S, Tzani P, Aiello M, Marangio E, Clini E, Chetta A. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves cardiovascular response to exercise in COPD. Respiration Epub 2013/05/23.

- Burgel PR, Nesme-Meyer P, Chanez P, Caillaud D, Carre P, Perez T, Cough and sputum production are associated with frequent exacerbations and hospitalizations in COPD subjects. Chest 2009; 135(4):975–982.

- Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P. Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 153(5):1530–1535.