Abstract

Background: This is the 30th Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ (AAPCC) National Poison Data System (NPDS). As of July 1, 2012, 57 of the nation's poison centers (PCs) uploaded case data automatically to NPDS. The upload interval was 7.58 [6.30, 11.22] (median [25%, 75%]) min, creating a near real-time national exposure and information database and surveillance system.

Methodology: We analyzed the case data tabulating specific indices from NPDS. The methodology was similar to that of previous years. Where changes were introduced, the differences are identified. Poison center cases with medical outcomes of death were evaluated by a team of 34 medical and clinical toxicologist reviewers using an ordinal scale of 1–6 to assess the Relative Contribution to Fatality (RCF) of the exposure to the death.

Results: In 2012, 3,373,025 closed encounters were logged by NPDS: 2,275,141 human exposures, 66,440 animal exposures, 1,025,547 information calls, 5,679 human confirmed nonexposures, and 218 animal confirmed nonexposures. Total encounters showed a 6.9% decline from 2011, while healthcare facility (HCF) exposure calls increased by 1.2%. All information calls decreased by 14.8% and HCF information calls decreased by 1.7%, medication identification requests (Drug ID) decreased by 22.0%, and human exposures reported to US PCs decreased by 2.5%. Human exposures with less serious outcomes have decreased by 3.7% per year since 2008, while those with more serious outcomes (moderate, major, or death) have increased by 4.6% per year since 2000.

The top five substance classes most frequently involved in all human exposures were analgesics (11.6%), cosmetics/personal care products (7.9%), household cleaning substances (7.2%), sedatives/hypnotics/antipsychotics (6.1%), and foreign bodies/toys/miscellaneous (4.1%). Analgesic exposures as a class increased the most rapidly (8,780 calls/year) over the last 12 years. The top five most common exposures in children aged 5 years or less were cosmetics/ personal care products (13.9%), analgesics (9.9%), household cleaning substances (9.7%), foreign bodies/toys/ miscellaneous (7.0%), and topical preparations (6.3%). Drug identification requests comprised 54.4% of all information calls. NPDS documented 2,937 human exposures resulting in death with 2,576 human fatalities judged related (RCF of 1-Undoubtedly responsible, 2-Probably responsible, or 3-Contributory).

Conclusions: These data support the continued value of PC expertise and need for specialized medical toxicology information to manage the more severe exposures, despite a decrease in calls involving less severe exposures. Unintentional and intentional exposures continue to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the US. The near real-time, always current status of NPDS represents a national public health resource to collect and monitor US exposure cases and information calls. The continuing mission of NPDS is to provide a nationwide infrastructure for public health surveillance for all types of exposures, public health event identification, resilience response, and situational awareness tracking. NPDS is a model system for the nation and global public health.

WARNING: Comparison of exposure or outcome data from previous AAPCC Annual Reports is problematic. In particular, the identification of fatalities (attribution of a death to the exposure) differed from pre-2006 Annual Reports (see Fatality Case Review—Methods). Poison center death cases are described as all cases resulting in death and those determined to be exposure-related fatalities. Likewise, (Exposure Cases by Generic Category) since year 2006 restricts the breakdown including deaths to single-substance cases to improve precision and avoid misinterpretation.

Introduction

This is the 30th Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ (AAPCC; http://www.aapcc.org) National Poison Data System (NPDS). (Citation1) On January 1, 2012, 57 regional poison centers (PCs) serving the entire population of the 50 United States, American Samoa, District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands submitted information and exposure case data collected during the course of providing telephonic patient tailored exposure management and poison information.

NPDS is the data warehouse for the nation's 57 PCs. PCs place emphasis on exposure management, accurate data collection and coding, and responding to the continuing need for poison-related public and professional education. The PC's health care professionals are available free of charge to users, 24-hours a day, every day of the year. PCs respond to questions from the public, healthcare professionals, and public health agencies. The continuous staff dedication at the PCs is manifest as the number of exposure and information call encounters exceeds 3.3 million annually. Poison center encounters either involve an exposed human or animal (EXPOSURE CALL) or a request for information with no person or animal exposed to any foreign body, viral, bacterial, venomous, or chemical agent or commercial product (INFORMATION CALL).

The NPDS Products Database

The NPDS products database contains over 400,000 products ranging from viral and bacterial agents to commercial chemical and drug products. The products database is maintained and continuously updated by data analysts at the Micromedex Poisindex® System (Micromedex Healthcare Series [Internet database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics. A robust generic coding system categorizes the product data into 1014 generic codes. These generic codes collapse into Nonpharmaceutical (558) and Pharmaceutical (456) groups. These two groups are divided into Major (68) and Minor (176) categories. The generic coding schema undergoes continuous improvement through the work of the AAPCC–Micromedex Joint Coding Group. The group consists of AAPCC members and editorial and lexicon staff working to meet best terminology practices. The generic code system provides enhanced report granularity as reflected in . The following 19 generic codes were introduced in 2012:

Table: Generic Codes Added in 2012.

Because the new codes were added at different times during the year, the numbers in for these generic codes do not reflect the entire year. For completeness certain of these categories require customized data retrieval until these categories have been in place for a year or more.

Methods

Characterization of Participating PCs and Population Served

Fifty-seven participating centers submitted data to AAPCC through December 31, 2012. Fifty-four centers (95%) were accredited by AAPCC as of July 1, 2012. The entire population of the 50 states, American Samoa, the District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands was served by the US PC network in 2012.(Citation2,Citation3)

The average number of human exposure cases managed per day by all US PCs was 6,216. Similar to other years, higher volumes were observed in the warmer months, with a mean of 6,576 cases per day in July compared with 5,583 per day in December. On average, US PCs received a call about an actual human exposure every 13.9 sec.

Call Management—Specialized Poison Exposure Emergency Providers

Most PC operations management, clinical education, and instruction are directed by Managing Directors (most are PharmDs and RNs with American Board of Applied Toxicology [ABAT] board certification). Medical direction is provided by Medical Directors who are board-certified physician medical toxicologists. At some PCs, the Managing and Medical Director positions are held by the same person.

Calls received at US PCs are managed by healthcare professionals who have received specialized training in toxicology and managing exposure emergencies. These providers include medical and clinical toxicologists, registered nurses, doctors of pharmacy, pharmacists, chemists, hazardous materials specialists, and epidemiologists. Specialists in Poison Information (SPIs) are primarily registered nurses, PharmDs, and pharmacists who direct the public to the most appropriate level of care while also providing the most up-to-date management recommendations to healthcare providers caring for exposed patients. They may work under the supervision of a Certified Specialist in Poison Information (CSPI). SPIs must log a minimum of 2,000 calls over a 12-month period to become eligible to take the CSPI examination for certification in poison information. Poison Information Providers are allied healthcare professionals. They manage information-type and low acuity (non-hospital) calls and work under the supervision of a CSPI. Of note is the fact that no nursing or pharmacy school offers a toxicology curriculum designed for PC work and SPIs must be trained in programs offered by their respective PC. PCs undergo a rigorous accreditation process administered by the AAPCC and must be reaccredited every 5 years.

NPDS—Near Real-time Data Capture

Launched on 12 April 2006, NPDS is the data repository for all of the US PCs. In 2012, all 57 US PCs uploaded case data automatically to NPDS. All PCs submitted data in near real-time, making NPDS one of the few operational systems of its kind. Poison center staff record calls contemporaneously in 1 of 4 case data management systems. Each PC uploads case data automatically. The time to upload data for all PCs is 7.58 [6.30, 11.22] (median [25%, 75%]) min creating a real-time national exposure database and surveillance system.

The web-based NPDS software facilitates detection, analysis, and reporting of NPDS surveillance anomalies. System software offers a myriad of surveillance uses allowing AAPCC, its member centers, and public health agencies to utilize NPDS US exposure data. Users are able to access local and regional data for their own areas and view national aggregate data. The application allows for increased “drill-down” capability and mapping via a geographic information system. Custom surveillance definitions are available along with ad hoc reporting tools. Information in the NPDS database is dynamic. Each year the database is locked prior to extraction of annual report data to prevent inadvertent changes and ensure consistent, reproducible reports. The 2012 database was locked on 24 October 2013 at 17:24 EDT.

Annual Report Case Inclusion Criteria

The information in this report reflects only those cases that are not duplicates and classified by the PC as CLOSED. A case is closed when the PC has determined that no further follow-up/recommendations are required or no further information is available. Exposure cases are followed to obtain the most precise medical outcome possible. Depending on the case specifics, most calls are “closed” within a few hours of the initial call. Some calls regarding complex hospitalized patients or cases resulting in death may remain open for weeks or months while data continues to be collected. Follow-up calls provide a proven mechanism for monitoring the appropriateness of management recommendations, augmenting patient guidelines, and providing poison prevention education, enabling continual updates of case information as well as obtaining final/known medical outcome status to make the data collected as accurate and complete as possible.

Statistical Methods

All Tables except and were generated directly by the NPDS web-based application and can thus be reproduced by each center. The figures and statistics in and were created using SAS JMP version 9.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) on summary counts generated by the NPDS web-based application.

NPDS Surveillance

As previously noted, all of the active US PCs upload case data automatically to NPDS. This unique near real-time upload is the foundation of the NPDS surveillance system. This makes possible both spatial and temporal case volume and case-based surveillance. NPDS software allows creation of volume and case-based definitions. Definitions can be applied to national, regional, state, or ZIP code coverage areas. Geocentric definitions can also be created. This functionality is available not only to the AAPCC surveillance team, but also to every PC. PCs also have the ability to share NPDS real-time surveillance technology with external organizations such as their state and local health departments or other regulatory agencies. Another NPDS feature is the ability to generate system alerts on adverse drug events and other drug or commercial products of public health interest like contaminated food or product recalls. Thus NPDS can provide real-time adverse event monitoring and surveillance for resilience response and situational awareness.

Surveillance definitions can be created to monitor a variety of volume parameters or case-based definitions on any desired substance or commercial product in the Micromedex Poisindex products database and/or set of clinical effects or other parameters. The products database contains over 400,000 entries. Surveillance definitions may be constructed using volume or case-based definitions with a variety of mathematical options and historical baseline periods from 1 to 13 years. NPDS surveillance tools include the following:

Volume Alert Surveillance Definitions

Total Call Volume

Human Exposure Call Volume

Animal Exposure Call Volume

Information Call Volume

Clinical Effects Volume (signs and symptoms, or laboratory abnormalities)

Case-Based Surveillance Definitions utilizing various NPDS data fields linked in Boolean expressions

○ Substance

○ Clinical Effects

○ Species

○ Medical Outcome and others

Incoming data is monitored continuously and anomalous signals generate an automated email alert to the AAPCC's surveillance team or designated PC or public health agency staff. These anomaly alerts are reviewed daily by the AAPCC surveillance team, the PC, or the public health agency that created the surveillance definition. When reports of potential public health significance are detected, additional information is obtained via the NPDS surveillance correspondence system or phone as appropriate from reporting PCs. The PC then alerts their respective state or local health departments. Public health issues are brought to the attention of the Health Studies Branch, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (HSB/NCEH/CDC). This unique near real-time tracking ability is a unique feature offered by NPDS and the PCs.

AAPCC Surveillance Team clinical and medical toxicologists review surveillance definitions on a regular basis to fine-tune the queries. CDC, as well as State and local health departments with NPDS access as granted by their respective PCs, also have the ability to create surveillance definitions for routine surveillance tasks or to respond to emerging public health events.

Fatality Case Review and Abstract Selection

NPDS fatality cases can be recorded as DEATH or DEATH (INDIRECT REPORT). Medical outcome of death is by direct report. Deaths (indirect reports) are deaths that the PC acquired from medical examiners or media, but did not manage nor answer any questions related specifically to that death.

Although PCs may report death as an outcome, the death may not be the direct result of the exposure. We define exposure-related fatality as a death judged by the AAPCC Fatality Review Team to be at least contributory to the exposure. The definitions used for the Relative Contribution to Fatality (RCF) classification are defined in Appendix B and the methods to select abstracts for publications is described in Appendix C. For details of the AAPCC fatality review process, see the 2008 annual report.(Citation1)

Pediatric Fatality Case Review

A focused Pediatric Fatality Review team, comprised of four pediatric toxicologists, evaluated cases in patients under 18 years of age. The panel reviewed the documentation of all such cases, with specific focus on the conditions behind the poisoning exposure and on finding commonality which might inform efforts at prevention. The pediatric fatality cases reviewed exhibited a bimodal age distribution. Exposures causing death in children ≤ 5 years of age were mostly coded as “Unintentional-General”, while those in ages over 12 years were mostly “Intentional”. Often the Reason Code did not capture the complexities of the case. For example, there were few mentions of details such as the involvement of law enforcement or child protective services. While there were some complete and informative reports, in many narratives the circumstances which preceded the exposure thought responsible for the death were unclear or absent. In response to these findings, the pediatric fatality review team developed and distributed Pediatric Narrative Guidelines, with specific attention to the root cause of these cases. PCs are requested to heed these guidelines and the need for a more in-depth investigation of “causality.”

RESULTS

Information Calls to PCs

Data from 1,025,547 information calls to PCs in 2012 () was transmitted to NPDS, including calls in optional reporting categories such as prevention/safety/ education (28,019), administrative (28,638), and caller referral (52,061).

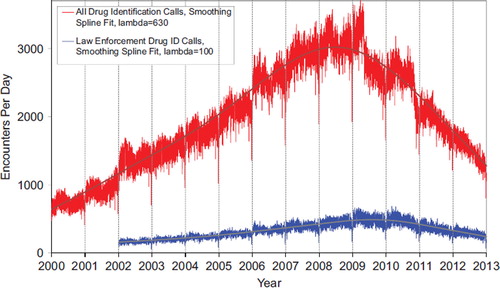

shows that All Drug ID calls decreased dramatically in mid 2009, again in late 2010 and late 2011 and continue to decrease in 2012. Law enforcement Drug ID Calls also showed a decline. The most frequent information call was for Drug ID, comprising 558,117 calls to PCs during the year. Of these, 328,858 (58.9%) were identified as drugs with known abuse potential; however, these cases were categorized based on the drug's abuse potential without knowledge of whether abuse was actually intended.

While the number of Drug Information calls decreased by 17.0% from 2011 (173,904 calls) to 2012 (144,267 calls), the distribution of these call types remained steady at 14.5% and 14.1%, respectively, of all information request calls. The most common drug information requests were in regards to therapeutic use and indications, followed by drug–drug interactions, questions about dosage, and inquiries of adverse effects. Environmental inquiries comprised 2.1% of all information calls. Of these environmental inquiries, questions related to cleanup of mercury (thermometers and other) remained the most common followed by questions involving pesticides.

Of all the information calls, poison information comprised 6.2% of the requests with inquiries involving general toxicity the most common followed by questions involving food preparation practices, safe use of household products, and plant toxicity.

Exposure Calls to PCs

In 2012, the participating PCs logged 3,373,025 total encounters including 2,275,141 closed human exposure cases (), 66,440 animal exposures (), 1,025,547 information calls (), 5,679 human confirmed non-exposures, and 218 animal confirmed non-exposures. An additional 574 calls were still open at the time of database lock. The cumulative AAPCC database now contains almost 58 million human exposure case records (). A total of 15,586,479 information calls have been logged by NPDS since the year 2001.

Table 1A. AAPCC Population Served and Reported Exposures (1983–2012).

Table 1B. Non-Human Exposures by Animal Type.

Table 1C. Distribution of Information Calls.

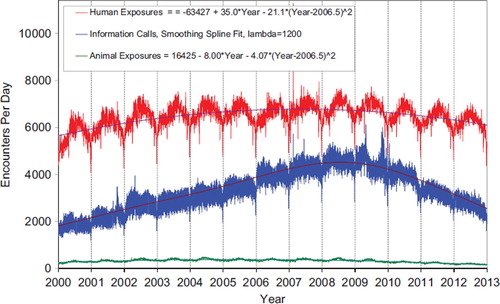

shows the human exposures, information calls, and animal exposures by day since January 1, 2001. Second order (quadratic) least squares regression of these data shows a statistically significant departure from linearity (declining rate of calls since mid 2007) for Human Exposure Calls. Information Calls are declining more rapidly than the quadratic regression this year, best described by a smoothing spline fit, and Animal Exposure Calls have likewise been declining since mid-2005.

Fig. 1. Human Exposure Calls, Information Calls, and Animal Exposure Calls by Day since January 1, 2000 Regression lines show least-squares second order regression—both linear and second order (quadratic) terms were statistically significant for Human Exposures and Animal Exposures (colour version of this figure can be found in the online version at www.informahealthcare.com/ctx).

A hallmark of PC case management is the use of follow-up calls to monitor case progress and medical outcome. US PCs made 2,702,081 follow-up calls in 2012. Follow-up calls were done in 46.2% of human exposure cases. One follow-up call was made in 22.4% of human exposure cases, and multiple follow-up calls (range 2–80) were placed in 23.8% of cases.

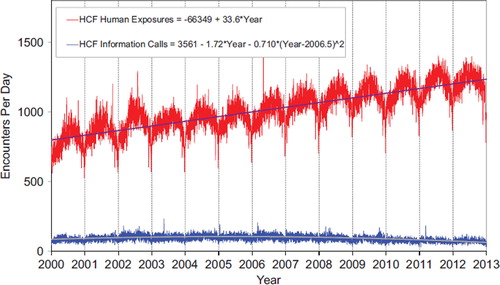

shows a graphic summary and analyses of HCF Exposure and HCF Information calls. HCF Exposure Calls did not depart from linearity (continued to increase at a steady rate), while the rate of HCF Information Calls has been declining since early 2005. This linearly increasing use of the PCs for the more serious exposures (HCF calls) is important in the face of the declining growth of all exposure and information calls. The May 2, 2006 exposure data spike on the Figure was the result of 602 children in a Midwest school reporting a noxious odor which caused anxiety, but resolved without sequelae.

Fig. 2. All Drug Identification and Law Enforcement Drug Identification Calls by Day since January 1, 2000 Smoothing Spline Fits were better than 2nd order regressions, R-Square = 0.796 for All Drug Identification Calls, R-Square = 0.632 Law Enforcement Drug ID Calls (colour version of this figure can be found in the online version at www.informahealthcare.com/ctx).

Fig. 3. HCF Exposure Calls and HCF Information Calls by Day since January 1, 2000 Regression lines show least-squares first and second order regressions—linear regression for HCF Exposure Calls (second order term was not statistically significant) and second order regression for HCF Information Calls. All terms shown were statistically significant for each of the two regressions (colour version of this figure can be found in the online version at www.informahealthcare.com/ctx).

(Nonpharmaceuticals) and 22B (Pharmaceuticals) provide summary demographic data on patient age, reason for exposure, medical outcome, and use of a HCF for all 2,275,141 human exposure cases, presented by substance categories.

Column 1: Name of the major, minor generic categories, and their associated generic codes.

Column 2: No. of Case Mentions (all exposures) in gray shading, displays the number of times the specific generic code was reported in all human exposure cases. If a human exposure case has multiple instances of a specific generic code it is only counted once.

Column 3: No. of Single Exposures This column was previously named ‘No. of `Single Exposures’ and was renamed in the 2009 report for clarity. This column displays the number of human exposure cases that identified only one substance (one case, one substance).

The succeeding columns (Age, Reason, Treatment Site, and Outcome) show selected detail from these single-substance exposure cases. Death cases include both cases that have the outcome of Death or Death (indirect report). These death cases are not limited by the relative contribution to fatality.

and 22B restrict the breakdown columns to single-substance cases. Prior to 2007, when multi-substance exposures were included, a relatively innocuous substance could be mentioned in a death column when, for example, the death was attributed to an antidepressant, opioid, or cyanide. This subtlety was not always appreciated by the user of this Table. The restriction of the breakdowns to single-substance exposures should increase precision and reduce misrepresentation of the results in this unique by-substance Table. Single-substance cases reflect the majority (89.4%) of all exposures. In contrast, only 41.9% of fatalities are single-substance exposures ().

and 22B tabulate 2,662,456 substance- exposures, of which 2,032,956 were single-substance exposures, including 1,052,906 (51.8%) nonpharmaceuticals and 980,050 (48.2%) pharmaceuticals. In 19.2% of single-substance exposures that involved pharmaceutical substances, the reason for exposure was intentional, compared with only 3.7% when the exposure involved a nonpharmaceutical substance. Correspondingly, treatment in a HCF was provided in a higher percentage of exposures that involved pharmaceutical substances (29.3%) compared with nonpharmaceutical substances (15.7%). Exposures to pharmaceuticals also had more severe outcomes. Of single-substance exposure-related fatal cases, 761 (69.6%) were pharmaceuticals compared with 333 (30.4%) nonpharmaceuticals.

Age and Gender Distributions

The age and gender distribution of human exposures is outlined in . Children younger than 3 years of age were involved in 35.7% of exposures and children younger than 6 years accounted for approximately half of all human exposures (48.4%). A male predominance was found among cases involving children younger than 13 years, but this gender distribution was reversed in teenagers and adults, with females comprising the majority of reported exposures.

Caller Site and Exposure Site

As shown in , of the 2,275,141 human exposures reported, 72.5% of calls originated from a residence (own or other) but 93.6% actually occurred at a residence (own or other). Another 19.5% of calls were made from a healthcare facility. Beyond residences, exposures occurred in the workplace in 1.6% of cases, schools (1.3%), healthcare facilities (0.3%), and restaurants or food services (0.2%).

Table 2. Site of Call and Site of Exposure, Human Exposure Cases.

Table 3A. Age and Gender Distribution of Human Exposures.

Table 3B. Population-Adjusted Exposures by Age Group.

Exposures in Pregnancy

Exposure during pregnancy occurred in 7,671 women (0.3% of all human exposures). Of those with known pregnancy duration (n = 7,149), 31.5% occurred in the first trimester, 37.1% in the second trimester, and 31.4% in the third trimester. Most of them (74.1%) were unintentional exposures and 19.5% were intentional exposures. There were four deaths in pregnant females in 2012.

Chronicity

Most human exposures, 2,006,316 (88.2%) were acute cases (single, repeated, or continuous exposure occurring over 8 hours or less) compared with 559 acute cases of 2,937 fatalities (19.0%). Chronic exposures (continuous or repeated exposures occurring over > 8 hours) comprised 2.1% (47,407) of all human exposures. Acute-on-chronic exposures (single exposure that was preceded by a continuous, repeated, or intermittent exposure occurring over a period greater than 8 hours) numbered 189,737 (8.3%).

Reason for Exposure

The reason category for most human exposures was unintentional (80.1%) with unintentional general (54.9%), therapeutic error (12.3%), and unintentional misuse (5.5%) of all exposures ().

Table 4. Distribution of Agea and Gender for Fatalitiesb.

Table 5. Number of Substances Involved in Human Exposure Cases.

Table 6A. Reason for Human Exposure Cases.

Scenarios

Of the total 296,666 therapeutic errors, the most common scenarios for all ages included inadvertent double-dosing (28.7%), wrong medication taken or given (15.7%), other incorrect dose (13.6%), doses given/taken too close together (9.7%), and inadvertent exposure to someone else's medication (8.3%). The types of therapeutic errors observed are different for each age group and are summarized in .

Table 6B. Scenarios for Therapeutic Errorsa by Ageb.

Reason by Age

Intentional exposures accounted for 16.0% of human exposures. Suicidal intent was suspected in 9.9% of cases, intentional misuse in 2.6% and intentional abuse in 2.5%. Unintentional exposures outnumbered intentional exposures in all age groups with the exception of ages 13– 19 years (). Intentional exposures were more frequently reported than unintentional exposures in patients aged 13–19 years. In contrast, of the 1,190 reported fatalities with RCF 1–3, the majority reason reported for children ≤ 5 years was unintentional, while most fatalities in adults (> 20 years) were intentional ().

Table 7. Distribution of Reason for Exposure by Age.

Table 8. Distribution of Reason for Exposure and Age for Fatalitiesa.

Route of Exposure

Ingestion was the route of exposure in 83.4% of cases (), followed in frequency by dermal (7.0%), inhalation/nasal (6.0%), and ocular routes (4.3%). For the 1,190 exposure-related fatalities, ingestion (84.5%), inhalation/nasal (8.6%), and parenteral (5.0%) were the predominant exposure routes. Each exposure case may have more than one route.

Table 9. Route of Exposure for Human Exposure Cases.

Clinical Effects

The NPDS database allows for the coding of up to 131 individual clinical effects (signs, symptoms, or laboratory abnormalities) for each case. Each clinical effect can be further defined as related, not related, or unknown if related. Clinical effects were coded in 841,775 (37.0%) cases (18.0% had 1 effect, 9.5% had 2 effects, 5.1% had 3 effects, 2.2% had 4 effects, 1.0% had 5 effects, and 1.2% had > 5 effects coded). Of clinical effects coded, 78.5% were deemed related to the exposure, 9.7% were considered not related, and 11.8% were coded as unknown if related.

Case Management Site

The majority of cases reported to PCs were managed in a nonHCF (69.2%), usually at the site of exposure, primarily the patient's own residence (). 1.6% of cases were referred to a HCF but refused referral. Treatment in a HCF was rendered in 27.0% of cases.

Table 10. Management Site of Human Exposures.

Of the 613,412 cases managed in a healthcare facility, 291,414 (47.5%) were treated and released, 100,455 (16.4%) were admitted for critical care, and 67,847 (11.1%) were admitted to a noncritical care unit.

The percentage of patients treated in a HCF varied considerably with age. Only 11.6% of children ≤ 5 years and only 14.0% of children between 6 and 12 years were managed in a HCF compared with 51.2% of teenagers (13–19 years) and 37.9% of adults (age ≥ 20 years).

Medical Outcome

displays the medical outcome of human exposure cases distributed by age. Older age groups exhibit a greater number of severe medical outcomes. compares medical outcome and reason for exposure and shows a greater frequency of serious outcomes in intentional exposures.

Table 11. Medical Outcome of Human Exposure Cases by Patient Age.a

Table 12. Medical Outcome by Reason for Exposure in Human Exposuresa.

The duration of effect is required for all cases which report at least one clinical effect and have a medical outcome of minor, moderate, or major effect (n = 515,287; 22.6% of exposures). demonstrates an increasing duration of the clinical effects observed with more severe outcomes.

Table 13. Duration of Clinical Effects by Medical Outcome.

Decontamination Procedures and Specific Antidotes

and outline the use of decontamination procedures, specific physiological antagonists (antidotes), and measures to enhance elimination in the treatment of patients reported in the NPDS database. These should be interpreted as minimum frequencies because of the limitations of telephonic data gathering.

Table 14. Decontamination and Therapeutic Interventions.

Table 15. Therapy Provided in Human Exposures by Age.

Ipecac-induced emesis for poisoning continues to decline as shown in and . Ipecac was administered in only 83 (0.01%) pediatric exposures in 2012. The continued decrease in ipecac syrup use over the last 2 decades was likely a result of ipecac use guidelines issued in 1997 by the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists and updated in 2004. (Citation5,Citation6) In a separate report, the American Academy of Pediatrics concluded not only that ipecac should no longer be used routinely as a home treatment strategy, but also recommended disposal of home ipecac stocks.(Citation7) A decline was also observed since the early 1990s for reported use of activated charcoal. While not as dramatic as the decline in use of ipecac, reported use of activated charcoal decreased from 3.7% of pediatric cases in 1993 to just 1.0% in 2012.

Table 16A. Decontamination Trends (1985–2012).

Table 16B. Decontamination Trends: Total Human and Pediatric Exposures ≤ 5 Yearsa.

Top Substances in Human Exposures

presents the most common 25 substance categories, listed by frequency of human exposure. This ranking provides an indication where prevention efforts might be focused, as well as the types of exposures PCs regularly manage. It is relevant to know whether exposures to these substances are increasing or decreasing.

Table 17A. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Human Exposures (Top 25).

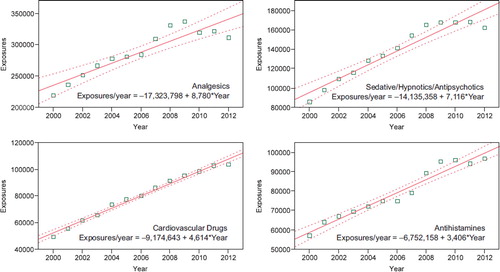

To better understand these relationships, we examined exposures per year over the last 12 years for the change over time for each of the 68 major generic categories via least squares linear regression. The exposure calls per year over this period were increasing for 37 and decreasing for 31 of the 68 categories. The change over time for the 12 yearly values was statistically significant (p < 0.05) for 53 of the 68 categories. shows the 25 categories which were increasing the most rapidly. Statistical significance of the linear regressions can be verified by noting the 95% confidence interval on the rate of increase excludes zero for all but 2 of the 25 categories. shows the linear regressions for the top four increasing categories in .

Table 17B. Substance Categories with the Greatest Rate of Exposure Increase (Top 25).

and present exposure results for children and adults, respectively, and show the differences between substance categories involved in pediatric and adult exposures.

Table 17C. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Pediatric (≤ 5 years) Exposures (Top 25).a

Table 17D. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Adult (≤ 20 years) Exposures (Top 25).a

reports the 25 categories of substances most frequently involved in pediatric (≤ 5 years) fatalities in 2012.

Table 17E. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Pediatric (≤ 5 years) Deaths.a

reports the 25 Drug ID categories most frequently queried in 2012. Unknown is the 5th and Miscellaneous the 18th most often identified drug category. These categories include medications which could not be identified, indicating the value of Drug ID information to the AAPCC, public health, public safety, and regulatory agencies. Internet-based resources do not afford the caller the option to speak with a healthcare professional if needed. Proper resources to continue this vital public service are essential, especially since the top 10 substance categories include antibiotics as well as drugs with widespread use and abuse potential such as opioids and benzodiazepines.

Table 17F. Substance Categories Most Frequently Identified in Drug Identification Calls (Top 25).

reports the 25 substance categories most frequently reported in exposures involving pregnant patients.

Table 17G. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Pregnant Exposuresa (Top 25).

Changes Over Time

Total encounters peaked in 2008 at 4,333,012 calls with 2,491,049 human exposure calls and 1,703,762 information calls. Total encounters decreased by 6.9% from 3,624,063 in 2011 to 3,373,025 in 2012. Information calls decreased by 14.8% from 1,203,282 calls in 2011 to 1,025,547 in 2012, with a 22.0% decrease in drug identification calls and a 1.7 % decrease in HCF information calls. Human exposures decreased by 2.5% from 2,334,004 to 2,275,141 cases.

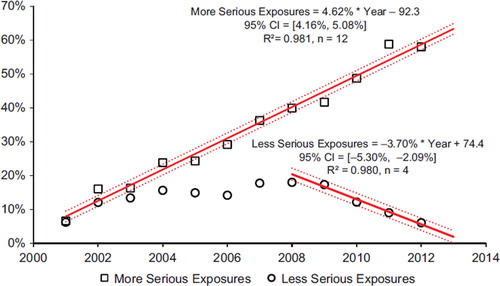

shows the year-to-year change through 2000 as a percentage of year 2000 for human exposure calls broken down into cases with more serious outcomes (death, major effect, and moderate effect) and less serious outcomes (minor effect, no effect, not followed (non-toxic), not followed (minimal toxicity possible), unable to follow (potentially toxic), and unrelated effect). Since 2000, cases with more serious outcomes have increased by + 4.6% (95% CI [4.2%, 5.1%]) per year from 108,148 cases in 2000 to 170,956 cases in 2012. However, cases with less serious outcomes have consistently decreased since 2008 by 3.7% (95% CI [− 5.3%, − 2.1%]) per year from 2,339,460 in 2008 to 2,102,755 cases in 2012. This has driven the overall decrease in human exposures since 2008.

Fig. 4. Change in Encounters by Outcome from 2008 to 2012. The Figure shows the percent change from baseline for Human Exposure Calls divided among the 10 Medical Outcomes. The More Serious Exposures (Major, Moderate, and Death) increased. The Less Serious Exposures (no effect, minor effect, not followed (non-toxic), not followed (minimal toxicity possible), unable to follow (potentially toxic), and unrelated effect) decreased after 2008. Solid lines show least-squares linear regressions for the change in More Serious Exposures per year (□) and Less Serious Exposures (○). Broken lines show 95% confidence interval on the regression (colour version of this figure can be found in the online version at www.informahealthcare.com/ctx).

Fig. 5. Substance Categories with the Greatest Rate of Exposure Increase (Top 4). Solid lines show least-squares linear regressions for the Human Exposure Calls per year for that category (□). Broken lines show 95% confidence interval on the regression (colour version of this figure can be found in the online version at www.informahealthcare.com/ctx).

Thus we see a consistent increase in exposure calls from HCFs () and for the more severe exposures (), despite a decrease in calls involving less severe exposures.

Distribution of Suicides

shows the modest variation in the distribution of suicides and pediatric deaths over the past 2 decades as reported to the NPDS national database. Within the last decade, the percent of exposures determined to be suspected suicides ranged from 30.3% to 53.9% and the percent of pediatric cases has ranged from 1.5% to 3.2%. The relatively large change seen for 2012 reflects the large increase in death (indirect reports) this year. Analyses of suicides and pediatric deaths for Direct and Indirect reports are shown in .

Table 18. Categories Associated with Largest Number of Fatalities (Top 25).a

Table 19A. Comparisons of Death Data (1985–2012).a

Table 19B. Comparisons of Direct and Indirect Death Data (2000–2012).a

Plant Exposures

provides the number of times the specific plant was reported to NPDS (N = 49,374). The 25 most commonly involved plant species and categories account for 39.7% of all plant exposures reported. The top three categories in the Table are essentially synonymous for unknown plant and comprise 12.2% (6,018/49,374) of all plant exposures. For a variety of reasons it was not possible to make a precise identification in these three groups. The top most frequent plant exposures where a positive plant identification was made were (descending order): Phytolacca americana (L.) (Botanic name), Spathiphyllum species (Botanic name), Ilex species (Botanic name), Philodendron species (Species unspecified), and Malus species (Botanical name).

Table 20. Frequency of Plant Exposures (Top 25).a

Deaths and Exposure-related Fatalities

A listing of cases () and summary of cases (, , , , , and ) are provided for fatal cases for which there exists reasonable confidence that the death was a result of that exposure (exposure-related fatalities). , , and 19 list all deaths, irrespective of the RCF. Beginning in 2010, cases with outcome of Death (Indirect Report) were not further reviewed by the AAPCC fatality review team and the RCF was determined by the individual PC review team.

Table 21. Listing of fatal nonpharmaceutical and pharmaceutical exposures.

Table 22A. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE Nonpharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category.

Table 22B. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE Pharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category.

There were 1,430 deaths (indirect) and 1,507 deaths. Of these 2,937 cases, 2,576 were judged exposure-related fatalities (RCF = 1-Undoubtedly responsible, 2-Probably responsible, or 3-Contributory). The remaining 361 cases were judged as follows: 79 as RCF = 4-Probably not responsible, 36 as 5-Clearly not responsible, and 246 as 6-Unknown.

Deaths are sorted in according to the category, then substance deemed most likely responsible for the death (Cause Rank), and then by patient age. The Cause Rank permits the PC to judge two or more substances as indistinguishable in terms of cause, for example, two substances which appear equally likely to have caused the death could have Substance Rank of 1,2 and Cause Rank of 1,1. Additional agents implicated are listed below the primary agent in the order of their contribution to the fatality.

As shown in , a single substance was implicated in 89.4% of reported human exposures, and 10.6% of patients were exposed to 2 or more drugs or products. The exposure-related fatalities involved a single substance in 498 cases (41.9%), 2 substances in 290 cases (24.4%), 3 in 166 cases (14.0%), and 4 or more in the balance of the cases.

In , the Annual Report ID number [bracketed] indicates that the abstract for that case is included in Appendix C. The letters following the Annual Report ID number indicate: i = Death (Indirect report) (occurred in 1,386, 53.8% of cases), p = prehospital cardiac and/or respiratory arrest (occurred in 423 of 2,576, 16.4% of cases), h = hospital records reviewed (occurred in 431, 16.7% of cases), a = autopsy report reviewed (occurred in 1,733, 67.3% of cases). The distribution of NPDS RCF was 1 = Undoubtedly responsible in 569 cases (22.1%), 2 = Probably responsible in 1,805 cases (70.1%), 3 = Contributory in 202 cases (7.8%). The denominator for these percentages in is 2,576.

All fatalities—all ages

presents the age and gender distribution for these 1,190 exposure-related fatalities (excluding death (indirect)). The age distribution of reported fatalities is similar to that in past years with 73 (6.1%) of the fatalities in children (< 20 years old), 1,114 of 1,190 (93.6%) of fatal cases occurring in adults (age ≥ 20 years) and 3 (0.3%) of fatalities occurring in Unknown Age patients. Although children ≤ 5 years old were involved in the majority of exposures, the 21 fatalities comprised just 1.8% of the exposure-related fatalities. Most (70.0%) of the fatalities occurred in 20–59-year-old individuals.

lists each of the 2,576 human fatalities (including death (indirect report)) along with all of the substances involved for each case. Please note: the substance listed in Column 3 of (alternate name) was chosen to be the most specific generic name based upon the Micromedex Poisindex product name and generic code selected for that substance. Alternate names are maintained in the NPDS for each substance involved in a fatality. The cross-references at the end of each major category section in list all cases that identify this substance as other than the primary substance. This Alternate name may not agree with the AAPCC generic categories used in the summary Tables (including ).

lists the top 25 minor generic substance categories associated with reported fatalities and the number of single-substance exposure fatalities for that category—miscellaneous sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics, miscellaneous cardiovascular drugs, opioids, and acetaminophen combination products, lead this list followed by miscellaneous stimulants and street drugs, acetaminophen alone, miscellaneous alcohols, miscellaneous antidepressants, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI). Note that is sorted by all substances to which a patient was exposed (i.e., a patient exposed to an opioid may have also been exposed to 1 or more other products) and shows single-substance exposures in the right hand column.

The first ranked substance () was a pharmaceutical in 2,142 (83.2%) of the 2,576 fatalities. These 2,142 first ranked pharmaceuticals included the following:

946 analgesics (178 methadone, 138 oxycodone, 133 acetaminophen/hydrocodone, 103 acetaminophen, 102 morphine, 53 fentanyl, 49 salicylate, 33 tramadol, and 24 acetaminophen/oxycodone)

559 stimulants/street drugs (325 heroin, 90 methamphetamine, 87 cocaine, and 14 amphetamines (hallucinogenic))

182 cardiovascular drugs (33 amlodipine, 21 metoprolol, 20 verapamil, 16 diltiazem (extended release), 13 diltiazem, 12 cardiac glycoside, and 10 atenolol)

149 antidepressants (38 amitriptyline, 19 bupropion, 14 citalopram, 12 bupropion (extended release), 11 doxepin, and 9 venlafaxine)

110 sedative/hypnotic/antipsychotics (35 quetiapine, 27 alprazolam, 9 benzodiazepine, 8 clonazepam, 7 diazepam, and 5 pentobarbital)

The exposure was acute in 1,467 (56.9%), A/C = acute on chronic in 260 (10.1%), C = chronic exposure in 87 (3.4%), and U = unknown in 762 (29.6%).

A total of 1,247 tissue concentrations for 1 or more related analytes were reported in 554 cases. Most of these (1,178) involved fatalities with RCF 1–3, and are listed in , while all tissue concentrations are available to the member centers through the NPDS Enterprise Reports. These 122 analytes included 212 acetaminophen, 93 ethanol, 82 salicylate, 35 morphine, 32 carboxyhemoglobin, 28 alprazolam, 28 diphenhydramine, 26 methadone, 24 ethylene glycol, 21 nordiazepam, 21 valproic acid, 20 bupropion, 20 diazepam, and 19 oxycodone.

Route of exposure was ingestion only in 1,511 cases (58.7%), parenteral in 104 cases (4.0%), and inhalation/nasal in 128 cases (5.0%). Most other routes were combination routes or unknown.

The Intentional exposure reason was suspected suicide in 786 cases (30.5%), abuse in 1,196 cases (46.4%), and misuse in 52 cases (2.0%). Unintentional exposure reason was environmental in 84 cases (3.3%), therapeutic error in 18 cases (0.7%), and misuse in 52 cases (2.0%). Adverse drug reaction was the reason in 45 (1.7%).

Pediatric fatalities—age ≤ 5 years

Although children younger than 6 years were involved in the majority of exposures, they comprised 46 of 2,937 (1.6%) of fatalities. These numbers are similar to those reported since 1985 (, all RCFs, and includes indirect deaths). (RCF 1–3, excludes indirect deaths) shows the percentage fatalities in children ≤ 5 years related to total pediatric exposures was 21/1,102,307 = 0.00191%. By comparison, 1,114/859,742 = 0.13% of all adult exposures involved a fatality. Of these 21 pediatric fatalities, 15 (71.4%) were reported as unintentional and 3 (14.3%) were coded as resulting from malicious intent ().

The 34 fatalities in children ≤ 5 years old in (includes death, indirect reports, and RCF 1–3) included 19 pharmaceuticals and 15 nonpharmaceuticals. The first ranked substances associated with these fatalities included smoke (7), antifreeze (ethylene glycol) (2), carbon monoxide (2), disc battery (2), lithium (2), morphine (2), and tramadol (2), and 15 other substances (1 each).

Pediatric fatalities—ages 6–12 years

In the age range 6–12 years, there were 7 reported fatalities, 4 of which were unintentional environmental, 1 was unintentional therapeutic error, 1 was intentional suspected suicide, and 1 unknown reason (). The 9 fatalities listed in (includes death, indirect reports, and RCF 1–3) included 3 carbon monoxide, 1 acetaminophen, 1 methadone, and 1 salicylate.

Adolescent fatalities—ages 13–19 years

In the age range 13–19 years, there were 45 reported fatalities including 38 intentional, 3 unintentional, and 4 unknown reason (). The 81 fatalities listed in (includes death, indirect reports, and RCF 1–3) included 71 pharmaceuticals and 10 nonpharmaceuticals. The first ranked pharmaceuticals associated with these fatalities included methadone (8 cases), heroin (6 cases), alprazolam (4 cases), oxycodone (4 cases), acetaminophen/hydrocodone (3 cases), morphine (3 cases), salicylate (3 cases), acetaminophen (2 cases), bupropion (2 cases), bupropion (extended release) (2 cases), drug unknown (2 cases), methamphetamine (2 cases), oxymorphone (2 cases), phenylethylamine (2 cases), quetiapine (2 cases), and the balance 1 substance each. The first ranked nonpharmaceuticals associated with these fatalities included carbon monoxide (3 cases), freon (2 cases), smoke (2 cases), ethanol (1 case), methanol (1 case), and selenous acid (1 case).

Pregnancy and Fatalities

A total of 30 deaths of pregnant women have been reported from the years 2000 through 2012. The majority (26 of 30) were intentional exposures (misuse, abuse, or suspected suicide). There were four deaths in pregnant women reported to NPDS in 2012.

AAPCC Surveillance Results

A key component of the NPDS surveillance system is the variety of monitoring tools available to the NPDS user community. In addition to AAPCC national surveillance definitions, 35 PCs utilize NPDS as part of their surveillance programs. Six state health departments plus CDC run surveillance definitions in NPDS. Since Surveillance Anomaly 1, generated at 2:00 pm EDT on 17 September 2006, over 210,000 anomalies have been detected. More than 1100 were confirmed as being of public health significance with PCs working collaboratively with their local and state health departments and in some instances CDC on the public health issues identified.

At the time of this report, 354 surveillance definitions run continuously, monitoring case and clinical effects volume and a variety of case-based definitions from food poisoning to nerve agents. These definitions represent the surveillance work by many PCs, state health departments, the AAPCC, and the Health Studies Branch, Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects, National Center for Environmental Health, CDC.

Automated surveillance continues to remain controversial as a viable methodology to detect the index case of a public health event. Uniform evaluation algorithms are not available to determine the optimal methodologies.(Citation8) Less controversial is the benefit to situational awareness that NPDS can provide.(Citation9) Typical NPDS surveillance data detects a response to an event rather than event prediction. This aids in situational awareness and resilience during and after a public health event.

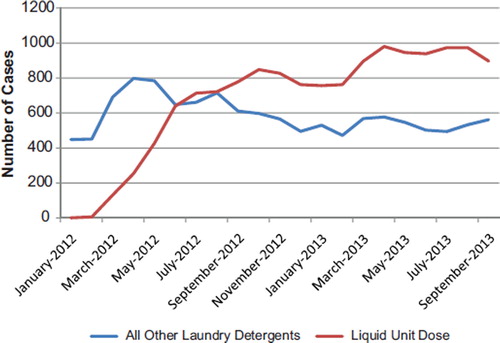

A current example of the involvement of the PC system and NPDS can be seen in the following. In February 2012, manufacturers began commercial distribution of unit dose liquid laundry detergent packets in the US. On May 4, 2012, a PC medical director reported two cases of unusual toxicity in toddlers with unit dose liquid laundry detergent packets exposures. From May 15–18, 2012, a number of other PCs reported additional cases of unusual toxicity. On May 17, 2012, AAPCC issued a press release and activated a temporary code to better capture the number of unit dose liquid laundry detergent packet cases using NPDS. In a May 23, 2012, ABC national news story on unit dose liquid laundry detergent toxicity in children using PC data, the manufacturer of one of the products announced a new child-proof container was planned. The American Cleaning Institute then partnered with AAPCC in June 2012 on a national campaign on the safe use of unit dose liquid laundry detergent packets.

A dramatic and sustained increase in number of calls about children exposed to unit dose liquid laundry detergent packets as a single substance has been noted and continues into 2013, while calls concerning all other laundry detergents have dropped (). The severity of exposures to unit dose liquid laundry detergent products as a single substance appears to be higher than older laundry formulations with, a 5-fold increase in major outcomes and a 2-fold increase in moderate outcomes. Some of the clinical effects showing increased frequency in these cases were esophageal injury, coma, respiratory depression, respiratory arrest, acidosis, dyspnea, and bronchospasm. Please note that the data for 2013 are considered preliminary because it is possible that a PC may update a case anytime during the year before the year is locked, if new information is obtained.

Fig. 6. Unit Dose Liquid Laundry Detergent Exposures, Jan 2012—Sep 2013. The Figure shows the number of calls received for single-substance human pediatric poison exposure calls to Unit Dose Liquid Laundry Detergents (![]()

Discussion

The exposure cases and information requests reported by PCs in 2012 do not reflect the full extent of PC efforts which also include poison prevention activities and public and healthcare professional education programs.

NPDS exposure data may be considered as providing “numerator data”, in the absence of a true denominator, that is, we do not know the number of actual exposures that occur in the population. NPDS data covers only those exposures which are reported to PCs.

NPDS 2000–2012 call volume data clearly demonstrate a continuing decrease in exposure calls. This decline has been apparent and increasing since mid-2007 and reflects the decreasing use of the PC for less severe exposures. However, in contrast, during this same period, exposures with a more severe outcome (death, major, and moderate) and HCF calls have continued a consistent increase. Possible contributors to the declining PC access include declining US birth (especially since exposure rates are much higher in children ≤ 5 years of age), increasing use of text rather than voice communication, and increased use of and reliance on internet search engines and web resources. To meet our public health goals, PCs will need to understand and meet the public's 21st century communication preferences. We are concerned that failure to respond to these changes may result in a retro-shift with more people seeking medical care for exposures that could have been managed at home by a PC. Likewise minor exposures may progress to more severe morbidity and mortality because of incorrect internet information or no telephone management. The net effect could be more severe poisoning outcomes because fewer people took advantage of PC services, with a resultant increased burden on the national healthcare infrastructure as may be reflected in the increased number of cases managed in a healthcare facility this year.

NPDS statistical analyses indicate that all analgesic exposures including opioids and sedatives are increasing year over year. This trend is shown in and . NPDS data mirrors CDC data that demonstrates similar findings.(Citation9) Thus NPDS provides a real-time view of these public health issues without the need for data source extrapolations.

One of the limitations of NPDS data has been the perceived lack of fatality case volume compared with other reporting sources. However, when change over time is studied, NPDS is clearly consistent with other public health fatality analyses. One of the issues leading to this concern is the fact that medical record systems seldom have common output streams. This is particularly apparent with the various electronic medical record systems available. It is important to build a federated approach similar to the one modeled by NPDS to allow data sharing, for example, between hospital emergency departments and other medical record systems including medical examiner offices nationwide. Enhancements to NPDS can promote interoperability between NPDS and electronic medical records systems to better trend poison-related morbidity and mortality in the US and internationally.

Summary

Unintentional and intentional exposures continue to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the US. The near real-time, always current status of NPDS represents a national public health resource to collect and monitor US exposure cases and information calls.

Changes in encounters in 2012 shown in include the following:

Total encounters (all exposure and information calls) decreased by 6.9%;

All information calls decreased by 14.8%, Drug ID calls decreased by 22.0%, and human exposures decreased by 2.5%;

HCF information calls decreased by 1.7%, while HCF exposures increased by 1.2%;

Human exposures with less serious outcomes decreased by 2.7%, while those with more serious outcomes (minor, moderate, major, or death) decreased by 0.5% not withstanding an overall 4.6% yearly increase since 2000;

The categories of substance exposures increasing most rapidly are analgesics, followed by sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics, cardiovascular drugs, and antihistamines.

These data support the continued value of PC expertise and need for specialized medical toxicology information to manage the more severe exposures, despite a decrease in calls involving less severe exposures. PCs must consider newer communication approaches that match current public communication patterns in addition to the traditional telephone call.

The continuing mission of NPDS is to provide a nationwide infrastructure for public health surveillance for all types of exposures, public health event identification, resilience response, and situational awareness tracking. NPDS is a model system for the nation and global public health.

Disclaimer

The American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC; http://www.aapcc.org) maintains the national database of information logged by the country's regional PCs serving all 50 United States, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. Case records in this database are from self-reported calls: they reflect only information provided when the public or healthcare professionals report an actual or potential exposure to a substance (e.g., an ingestion, inhalation, or topical exposure, etc.), or request information/educational materials. Exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. The AAPCC is not able to completely verify the accuracy of every report made to member centers. Additional exposures may go unreported to PCs and data referenced from the AAPCC should not be construed to represent the complete incidence of national exposures to any substance(s).

Notes

This report is published under contractual arrangement with AAPCC and does not undergo external peer-review.

References

- National Poison Data System: Annual reports 1983–2012 [Internet]. Alexandria (VA): American Association of Poison Control Centers;. Available from: http://www.aapcc.org/annual-reports/

- US Census Bureau. Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012 (NST-EST2012-01) [downloaded 2013 Oct 23] http://www.census.gov/popest/data/state/totals/2012/index.html

- US Census Bureau: International Data Base (IDB) Demographic Indicators for: American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Virgin Islands, [downloaded 2012 Oct 26]: http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/region.php

- US Census Bureau: State Characteristics Datasets: Annual Estimates of the Civilian Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States and States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012[downloaded 2013 Oct 23]: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/state/asrh/2012/SC-EST2012-AGESEX-CIV.html

- Position statement: ipecac syrup. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35:699–709.

- American Academy of Clinical Toxicology European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. Position Paper: Ipecac Syrup. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2004; 42: 133–143.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement. Poison treatment in the home. Pediatrics 2003; 112:1182–1185.

- Savel TG, Bronstein A, Duck, M, Rhodes MB, Lee, B, Stinn J, Worthen, K. Using Secure Web Services to Visualize Poison Center Data for Nationwide Biosurveillance: A Case Study [Internet]. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics 2010; 2:1–9; [downloaded 2012 Oct 30] http://ojphi.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/ojphi/article/view/2920/2505

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. QuickStats: Number of Poisoning Deaths* Involving Opioid Analgesics and Other Drugs or Substances – United States, 1999—2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010; 59:1026.

- McGraw-Hill's AccessMedicine, Laboratory Values of Clinical Importance (Appendix), Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 17e. McGraw-Hill Professional, 2008 [cited 2010 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www.accessmedicine.com/.

- Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies, Ninth Edition, McGraw-Hill Companies, 2010.

- Dart RC, editor. Medical Toxicology, Third Edition. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Appendix A—Acknowledgments

The compilation of the data presented in this report was supported in part through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention AAPCC Contract 200-2011-41767.

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the following individuals who assisted in the preparation of the manuscript: Katherine W. Worthen and Laura J. Rivers.

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the staff at the AAPCC Central Office for their support during the preparation of the manuscript: John Fiegel, MS, CAE, Interim Executive Director, Beth Doggette, and the entire staff.

Poison Centers

We gratefully acknowledge the extensive contributions of each participating PC and the assistance of the many healthcare providers who provided comprehensive data to the PCs for inclusion in this database. We especially acknowledge the dedicated efforts of the SPIs who meticulously coded 3,373,025 calls made to US PCs in 2012.

As in previous years, the initial review of reported fatalities and development of the abstracts and case data for NPDS was the responsibility of the staff at the 57 participating PCs. Many individuals at each center participated in the fatality case preparation. These toxicology professionals and their centers are the following:

Alabama Poison Center

Perry Lovely, MD, ACMT

John Fisher, PharmD, DABAT, FAACT

Lois Dorough BSN, RN, CSPI

Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center

Keith Boesen, PharmD, CSPI

F. Mazda Shirazi, MS, MD, PhD, FACEP

Arkansas Poison and Drug Information Center

Henry F. Simmons, Jr., MD

Pamala R. Rossi, PharmD

Howell Foster, PharmD

Banner Good Samaritan Poison and Drug Information Center

Daniel Brooks, MD

Belinda Sawyers, RN, CSPI

Jane Klemens, RN, CSPI

Sharyn Welch, RN

Blue Ridge Poison Center

Christopher P. Holstege, MD

Nathan P. Charlton, MD

William Rushton, MD

Luke Hardison, MD

California Poison Control System—Fresno/Madera Division

Richard J. Geller, MD, MPH

California Poison Control System—Sacramento Division

Timothy Albertson, MD, PhD

Justin Lewis, PharmD, CSPI

California Poison Control System—San Diego Division

Richard F. Clark, MD

Lee Cantrell, PharmD

Michael Durracq, MD

Jennifer Cullen, MD

Landon Rentmeester, MD

California Poison Control System—San Francisco

Kent R. Olson, MD

Susan Kim-Katz, PharmD

Raymond Ho, PharmD

Kathryn Meier, PharmD

Sandra Hayashi, PharmD

Suad A. Al-Abri, MD

Gabriela Cordero-Schmidt, MD

Freda Rowley, PharmD

Ilene Anderson, PharmD

Jo Ellen Dyer, PharmD

Beth Manning, PharmD

Ben Tsutaoka, PharmD

Carolinas Poison Center

Michael C. Beuhler, MD

Marsha Ford, MD

Anna Rouse Dulaney, PharmD

William Kerns II, MD

Christine M. Murphy, MD

Steven J Walsh, MD

Central Ohio Poison Center

Hannah Hays, MD

Marcel J. Casavant, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Henry Spiller, MS, DABAT, FAACT

Jason Russell, DO

Devin Wiles DO

Kaitlyn Day

Central Texas Poison Center

Ryan Morrissey, MD

S. David Baker, PharmD, DABAT

Children's Hospital of MI Regional Poison Center

Cynthia Aaron, MD

Lydia Baltarowich, MD

Aimee Nefcy, MD

Bram Dolcourt, MD

Susan C. Smolinske, PharmD

Matthew Hedge, MD

Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center

Shan Yin, MD, MPH

Sara Pinkston, RN

Connecticut Poison Center

Charles McKay, MD

Kathy Hart MD

Bernard C. Sangalli, MS

Florida/USVI Poison Information Center—Jacksonville

Thomas Kunisaki, MD, FACEP, ACMT

Florida Poison Information Center—Miami

Jeffrey N. Bernstein, MD

Richard S. Weisman, PharmD

Florida Poison Information Center—Tampa

Alfred Aleguas, Jr., BS Pharm, PharmD, DABAT

Cynthia R. Lewis-Younger, MD, MPH

Pam Eubank, RN, CSPI

Shirley Rendon, MD, CSPI

Judy Turner, RN, CSPI

Georgia Poison Center

Robert J. Geller, MD

Brent W. Morgan, MD

Ziad Kazzi, MD

Stella Wong, DO

Gaylord P. Lopez, PharmD

Stephanie Hon, PharmD

Adam Pomerleau, MD

Justin Arnold, DO

Alaina Steck, MD

Melissa Halliday, MD

Molly Boyd, MD

Hennepin Regional Poison Center

Deborah L. Anderson, PharmD

Jon B. Cole, MD

JoAn Laes, MD

Benjamin S. Orozco, MD

David J. Roberts, MD

Laurie Willhite, PharmD, CSPI

Illinois Poison Center

Michael Wahl, MD

Sean Bryant, MD

Indiana Poison Center

James B. Mowry, PharmD

Gwenn Christianson, MSN, CSPI

R. Brent Furbee, MD

Iowa Poison Control Center

Sue Ringling, RN

Linda B. Kalin, RN

Edward Bottei, MD

Kentucky Regional Poison Center

George M. Bosse, MD

Barbara M Chenault RN CSPI

Louisiana Poison Center

Mark Ryan, PharmD

Thomas Arnold, MD

Maryland Poison Center

Suzanne Doyon, MD, FACMT

Mississippi Poison Control Center

Robert Cox MD, PhD, DABT, FACMT

Christina Parker, Rn, CSPI

Missouri Poison Center at SSM Cardinal Glennon

Children's Medical Center

Anthony Scalzo, MD, FACMT, FAAP, FAACT

Shelly Enders, PharmD, CSPI

National Capital Poison Center

Cathleen Clancy, MD, FACMT

Nicole Reid, RN, BA, BSN, MEd, CSPI

Nebraska Regional Poison Center

Claudia Barthold, MD

Ronald I. Kirschner, MD

New Jersey Poison Information and Education System

Steven M. Marcus, MD

Bruce Ruck, PharmD

New Mexico Poison and Drug Information Center

Steven A. Seifert, MD, FAACT, FACMT

Blaine E. (Jess) Benson, PharmD, DABAT

New York City Poison Control Center

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, MS, RPh

Robert S. Hoffman, MD

Lewis Nelson, MD

Rana Biary, MD

Nicholas Connors, MD

Mai Takematsu, MD

Betty Chen, MD

Lauren Shawn, MD

Hong Kim, MD

North Texas Poison Center

Brett Roth MD, ACMT, FACMT

Melody Gardner, RN, MSN, MHA, CCRN

Northern Ohio Poison Center

Lawrence S. Quang, MD

Adrianne Grendzynski, RN, BSN, CSPI

Danielle Richardson, RN, BSN, CSPI

Susan Scruton, RN, BSN, CSPI

Northern New England Poison Center

Jane Clark

Tamas Peredy, MD

Oklahoma Poison Control Center

William Banner, Jr., MD, PhD, ABMT

Scott Schaeffer, RPh, DABAT

Oregon Poison Center

Zane Horowitz, MD

Sandra L. Giffin, RN, MS

Palmetto Poison Center

William H. Richardson, MD

Jill E. Michels, PharmD

Pittsburgh Poison Center

Michael Lynch, MD

Rita Mrvos, BSN

Edward P. Krenzelok, PharmD

Puerto Rico Poison Center

José Eric Dîaz-Alcalá, MD

Andrés Britt, MD

Elba Hernández, RN

Regional Center for Poison Control and Prevention Serving Massachusetts and Rhode Island

Michele Burns Ewald, MD, MPH

Dennis Wigandt, PharmD

May Yen, MD

Diana Felton, MD

Regional Poison Control Center—Children's of Alabama

Erica Liebelt, MD, FACMT

Michele Nichols, MD

Sherrel Brooks, RN, CSPI

Ann Slattery DrPH DABAT

Diane Smith, RN, CSPI

Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center

Alvin C. Bronstein, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Beau Braden DO, MPH, MS

Janetta L. Iwanicki, MD

Joseph Maddry, MD

Daniel Sessions, MD

Sam Wang, MD

Shireen Banerji, PharmD, DABAT

Carol Hesse RN, CSPI

Regina R. Padilla

South Texas Poison Center

Cynthia Abbott-Teter, PharmD

Douglas Cobb, RPh

Miguel C. Fernandez, MD

George Layton, MD

C. Lizette Villarreal, MA

Southeast Texas Poison Center

Wayne R. Snodgrass, MD, PhD, FACMT

Jon D. Thompson, MS, DABAT

Jean L. Cleary, PharmD, CSPI

Tennessee Poison Center

John G. Benitez, MD, MPH

Saralyn Williams, MD

Donna Seger, MD

Texas Panhandle Poison Center

Shu Shum, MD

Jeanie E. Jaramillo, PharmD

Cristie Johnston, RN, CSPI

The Poison Control Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Fred Henretig, MD

Kevin Osterhoudt, MD

University of Kansas Hospital Poison Control Center

Tama Sawyer, PharmD, DABAT

Stephen Thornton, MD

Upstate NY Poison Center

Jeanna M. Marraffa, PharmD

Alexander Garrard, Pharm.D.

Christine M. Stork, PharmD

Timothy Wiegand, MD

Utah Poison Control Center

B. Zane Horowitz, MD

Tom Martin, MD, MPH, FACEP

Virginia Poison Center

Rutherfoord Rose, PharmD

Kirk Cumpston, DO

Brandon Wills, DO

Paul Stromberg, MD

Washington Poison Center

William T. Hurley, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Curtis Elko, PharmD

David Serafin, CPIP

West Texas Regional Poison Center

Stephen W. Borron, MD, MS, FACEP, FACMT

Salvador H. Baeza, PharmD, DABAT

Hector L. Rivera, RPh, CSPI

West Virginia Poison Center

Elizabeth J. Scharman, PharmD, DABAT, BCPS, FAACT

Anthony F. Pizon, MD, ABMT

Wisconsin Poison Center

David D. Gummin, MD

Lori Rohde, RN, CSPI

Amy E. Zosel MD

AAPCC Fatality Review Team

The Lead and Peer review of the 2012 fatalities was carried out by the 34 individuals listed here including 4 who reviewed the pediatric cases [Peds]. The authors and the AAPCC wish to express our appreciation for their volunteerism, dedication, hard work, and good will in completing this task in a limited time.

Alfred Aleguas Jr, PharmD, DABAT, Florida Poison Information Center—Tampa

Anna Rouse Dulaney*, PharmD, DABAT, Carolinas Poison Center

Ann-Jeannette Geib*, MD, Robert Wood Johnson Med School, New Brunswick, NJ

Bernard C Sangalli*, MS, DABAT, Connecticut Poison Center

Charles McKay, MD, Connecticut Poison Center

Christine Murphy, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Medical Toxicology, Carolinas Medical Center/Carolinas Poison Center, Charlotte, NC

Curtis Elko, CSPI, Washington Poison Center, Seattle

Cynthia Lewis-Younger, MD, MPH, Florida Poison Information Center—Tampa

Daniel E. Brooks, MD, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix

David D Gummin, MD, Wisconsin Poison Center

Diane Calello, MD, New Jersey Poison Information and Education System [Peds]

Elizabeth J Scharman, PharmD, DABAT, BCPS, FAACT, West Virginia Poison Center

Gar Chan, MD, Launceston General Hospital, Tasmania, Australia

Henry Spiller, MS, DABAT, FAACT, Central Ohio Poison Center, Columbus

Jan Scaglione, PharmD, DBAT, Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center

Jeffrey S Fine, MD, NYU School of Medicine/Bellevue Hospital [Peds]

Jennifer Lowry, MD, Clin Pharm & Med Tox, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO [Peds]

Jill E. Michels, PharmD, DABAT, Palmetto Poison Center, SC

John McDonagh, MD, Hartford, CT

Karen E Simone, PharmD, DABAT, Northern New England PC, Maine Medical Center

Kathy Hart, MD, Connecticut Poison Control Center

L Keith French, MD, Oregon Poison Center

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, RPh, MS, DABAT, FAACT, NYC Poison Control Center

Mark Su, MD, FACEP, FACMT, North Shore University Hospital, NY

Mike Levine*, MD, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix

Nathanael McKeown*, DO, Oregon Poison Center

Rachel Gorodetsky, PharmD, D’Youville College School of Pharmacy, University of Rochester Medical Center

Rais Vohra*, MD, California Poison Control System, Fresno/Madera

Robert B Palmer, PhD, DABAT, Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center, Denver, CO

Robert Goetz, PharmD, DBAT, Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center

Steven M. Marcus, MD, NJ Poison Information and Education System, [Peds]

Susan Smolinske, PharmD, Children's Hospital of Michigan RPCC, Detroit

Timothy Wiegand, MD, Director of Toxicology, University of Rochester, Medical Center and Strong Memorial Hospital; Consultant Toxicologist, SUNY Upstate Poison Center

William Hurley, MD, Washington Poison Center, Seattle

* These reviewers further volunteered to read the top-ranked 200 abstracts and judged to publish or omit each.

AAPCC Micromedex Joint Coding Group

Chair: Elizabeth J. Scharman, Pharm.D., DABAT, BCPS, FAACT

Alvin C. Bronstein, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Rick Caldwell

Christina Davis, PharmD

Sandy Giffin, RN, MS

Kendra Grande, RPh

Katherine M. Hurlbut, MD

Wendy Klein-Schwartz, PharmD, MPH

Fiona McNaughton

James Mowry, PharmD

Susan C. Smolinske, PharmD

AAPCC Rapid Coding Team

Chair: Alvin C. Bronstein, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Elizabeth J. Scharman, Pharm.D., DABAT, BCPS, FAACT

Jay L. Schauben, PharmD, DABAT, FAACT

Susan C. Smolinske, PharmD

AAPCC Surveillance Team

NPDS surveillance anomalies are analyzed daily by a team of ten medical and clinical toxicologists working across the country in a distributed system. These dedicated professionals interface with the HSB/NCEH/CDC and the PCs on a regular basis to identify anomalies of public health significance and improve NPDS surveillance systems:

Alfred Aleguas, Pharm D, DABAT

S. David Baker, PharmD, DABAT

Director, Alvin C. Bronstein, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Douglas J. Borys, PharmD, DABAT

John Fisher, PharmD, DABAT, FAACT

Jeanna M. Marraffa, PharmD, DABAT

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, RPH, MS, DABAT, FAACT

Henry A. Spiller, MS, DABAT, FAACT

Richard G. Thomas, Pharm D, DABAT

Regional Poison Center Fatality Awards

Each year the AAPCC and the Fatality Review team recognized several regional PCs for their extra effort in their preparation of fatality reports and prompt responses to reviewer queries during the review process. The awards were presented at the October 2013, North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology meeting in Atlanta, GA.

First Center to Complete all Cases (December 15, 2012, last of their 16 cases)

Nebraska Regional Poison Center (Omaha)

Largest Number with Autopsy Reports (57 of 79 cases)

Carolinas Poison Center (Charlotte)

Highest Percentage with Autopsy Reports (80% of 15 cases)

Central Ohio Poison Center (Columbus)

Largest Number of INDIRECT cases (759 of 1409 total cases reported for 2012)

Maryland Poison Center (Baltimore)

Highest Overall Quality of Reports (12.5 of possible 22 for 16 cases)

University of Kansas Hospital Poison Control Center (Kansas City)

Greatest improvement in Overall Quality of Reports (2.81 increase from last year)

University of Kansas Hospital Poison Control Center (Kansas City)

Most Abstracts Published in last year's Annual report (9 of the 68 published narratives) Maryland Poison Center (Baltimore)

Most Helpful Regional Poison Center Staff (based on survey of AAPCC review team) Missouri Regional Poison Center (St. Louis)

Honorable mention

Carolinas Poison Center (Charlotte)

Appendix B—Data Definitions

Reason for Exposure

NPDS classifies all calls as either EXPOSURE (concern about an exposure to a substance) or INFORMATION (no exposed human or animal). A call may provide information about one or more exposed person or animal (receptors).

SPIs coded the reasons for exposure reported by callers to PCs according to the following definitions:

Unintentional general: All unintentional exposures not otherwise defined below.

Environmental: Any passive, non-occupational exposure that results from contamination of air, water, or soil. Environmental exposures are usually caused by manmade contaminants.

Occupational: An exposure that occurs as a direct result of the person being on the job or in the workplace.

Therapeutic error: An unintentional deviation from a proper therapeutic regimen that results in the wrong dose, incorrect route of administration, administration to the wrong person, or administration of the wrong substance. Only exposures to medications or products used as medications are included. Drug interactions resulting from unintentional administration of drugs or foods which are known to interact are also included.

Unintentional misuse: Unintentional improper or incorrect use of a nonpharmaceutical substance. Unintentional misuse differs from intentional misuse in that the exposure was unplanned or not foreseen by the patient.

Bite/sting: All animal bites and stings, with or without envenomation, are included.

Food poisoning: Suspected or confirmed food poisoning; ingestion of food contaminated with microorganisms is included.

Unintentional unknown: An exposure determined to be unintentional, but the exact reason is unknown.

Suspected suicidal: An exposure resulting from the inappropriate use of a substance for reasons that are suspected to be self-destructive or manipulative.

Intentional misuse: An exposure resulting from the intentional improper or incorrect use.

Intentional abuse: An exposure resulting from the intentional improper or incorrect use of a substance where the patient was likely attempting to gain a high, euphoric effect or some other psychotropic effect, including recreational use of a substance for any effect.

Intentional unknown: An exposure that is determined to be intentional but the specific motive is unknown.

Contaminant/tampering: The patient is an unintentional victim of a substance that has been adulterated (either maliciously or unintentionally) by the introduction of an undesirable substance.

Malicious: Patients who are victims of another person’s intent to harm them.

Withdrawal: Inquiry about or experiencing of symptoms from a decline in blood concentration of a pharmaceutical or other substance after discontinuing therapeutic use or abuse of that substance.