Abstract

Background and purpose Different results after shoulder arthroplasty have been found for different diagnostic groups. We evaluated function, pain, and quality of life after shoulder arthroplasty in 4 diagnostic groups.

Patients and methods Patients with shoulder arthroplasties registered in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register from 1994 through 2008 were posted a questionnaire in 2010. 1,107 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis (OA), acute fracture (AF), or fracture sequela (FS) returned completed forms (65% response rate). The primary outcome measure was the Oxford shoulder score (OSS), which assesses symptoms and function experienced by the patient on a scale from 0 to 48. A secondary outcome measure was the EQ-5D, which assesses life quality. The patients completed a questionnaire concerning symptoms 1 month before surgery, and another concerning the month before they received the questionnaire.

Results Patients with RA and OA had the best results with a mean improvement in OSS of 16 units, as opposed to 11 for FS patients. Both shoulder pain and function had improved substantially. The change in OSS for patients with AF was negative (–11), but similar end results were obtained for AF patients as for RA and OA patients. Quality of life had improved in patients with RA, OA, and FS.

Interpretation Good results in terms of pain relief and improved level of function were obtained after shoulder arthroplasty for patients with RA, OA, and—to a lesser degree—FS. A shoulder arthropathy had a major effect on quality of life, and treatment with shoulder replacement substantially improved it.

Results after shoulder arthroplasty have traditionally been presented as revision rates. A study on implant survival of 1,825 shoulder arthroplasties registered in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) (Fevang et al. Citation2009) confirmed other studies showing different prosthesis survival rates for different diagnostic groups (Trail and Nuttall Citation2002, Robinson et al. Citation2003, Sperling et al. Citation2007, Fevang et al. Citation2009). Furthermore, few randomized controlled trials have been performed to study shoulder replacement (Gartsman et al. Citation2000, Boileau et al. Citation2002, Lo et al. Citation2005, Kircher et al. Citation2009, Rahme et al. Citation2009).

Since the introduction of the Oxford shoulder score (OSS) in 1996, its use has increased and it is now used in several countries (Cloke et al. Citation2005, Flinkkila et al. Citation2006, Rosenberg and Soudry Citation2006). It is used as an outcome measure in the New Zealand National Joint Registry. In a study of shoulder hemiarthroplasty, Rees et al. (Citation2010) used the OSS to assess patient-reported outcome and found that this score provided valuable information about patient function and pain that was not detected using survival analysis. A recent paper described the OSS as a valid and feasible measure of shoulder function in patients with rheumatic diseases who undergo shoulder surgery (Christie et al. Citation2009).

In a previous study on knee arthroplasty comparing 3 implant types, revision rates were found to be similar but the level of pain differed between patients with different brands of prosthesis (Murray and Frost Citation1998). This illustrates how revision rate does not fully reflect the results of an arthroplasty procedure. With this background, we conducted a study of function, pain, and quality of life in patients with shoulder prostheses in Norway. The main purpose of our study was to evaluate these factors in 4 major diagnostic groups.

Material and methods

Patients

All patients 18 years or older with a shoulder arthroplasty that was reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) from 1994 through 2008 for any diagnosis except cancer, were sent a paper questionnaire during February 2010 (n = 1,865). A reminder was sent to non-responders in June 2010. 662 patients did not return the questionnaire (). 1,203 patients returned completed forms (65% responder rate), but only patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA; n = 253), osteoarthritis (OA; n = 388), acute fracture (AF; n = 248), or fracture sequelae (FS; n = 218) were included in the analysis, giving a study population of 1,107 patients.

Table 1. Characteristics of non-responders and responders

From the NAR, data on patient demographics (), diagnosis, type of prosthesis, date of surgery, and information on revision surgery were collected. More than 1 diagnosis was allowed, but for this study each patient was assigned 1 diagnosis according to a system where AF ranked above all other diagnoses, FS ranked above RA and OA, and RA ranked above OA.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with the four major diagnoses

A revision was defined as an exchange or removal of parts of the implant or the whole implant. 75 patients underwent at least 1 revision operation. These patients were included because we found it of equal interest to evaluate the end results (pain, function, and quality of life) for these patients as for those who were not reoperated. The patients were specifically asked to consider the time before the primary operation when answering the questionnaire regarding preoperative status.

All patients received a patient information letter and signed a consent form, which was returned together with the questionnaire. The project was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, Western Norway (date of issue: 07/01/2009; registration number: 246:09).

A complete list of all prosthesis brands used in the study can be found in the annual report for 2010 from the NAR (http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/default.htm).

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the OSS, which assesses symptoms and function experienced by patients in relation to shoulder surgery (Dawson et al. Citation1996). The OSS is suitable for evaluation of all types of shoulder surgery except surgery for instability. It contains 12 items, each with 5 response options, scored from 0 to 4. A single figure ranging from 0 to 48 is obtained by adding the scores from the 12 items, and 0 represents the worst possible state. The OSS has been shown to be consistent, reliable, valid, and sensitive to clinical change (Dawson et al. Citation1996, Christie et al. Citation2009, Desai et al. Citation2010).

The patients completed one questionnaire concerning symptoms and function 1 month before surgery and another concerning symptoms and function at the time of receiving the questionnaire. In addition to the total OSS, an OSS pain score was calculated on the basis of the 4 questions relating to pain (i.e. usual degree of pain, and pain at night) and an OSS function score was calculated based on the 8 questions concerning activities (i.e. dressing, shopping, and eating) (). The pain score ranged from 0 to 16 and the function score from 0 to 32.

The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the OSS has been suggested to be 4.5 points (Wilson et al. Citation2009), which is approximately 10% of the total score, and we used this as the limit for an MCID. The patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS) is defined as the highest level of symptoms that patients consider acceptable or satisfactory (Tubach et al. Citation2006). Based on the PASS threshold for the OSS estimated in a recent study, we calculated the percentage of patients with PASS (Christie et al. Citation2011). In that study, the old OSS was used and the PASS threshold was found to be around 27, which corresponds to 33 in the new OSS.

The OSS was translated into Norwegian by 4 researchers (1 orthopedic surgeon, 1 rheumatologist, 1 statistician, and 1 medical student). The translation was evaluated by a bilingual orthopedic surgeon, and a blinded back-translation was then done.

The secondary outcome measure was the EQ-5D (http://www.euroqol.org/home.html), which is a self-administered questionnaire with 2 sections. The first part consists of 5 questions concerning 5 dimensions of life: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, each of which is scored from 1 to 3. The EQ-5D index score is calculated using population-based preference weights and the score ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 represents perfect health and 0 is death. Negative values are allowed, and represent a health status considered to be worse than death. The second part is a 20-cm vertical visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 is the worst imaginable health state and 100 is the best imaginable health state.

Statistics

Paired t-tests were used to compare preoperative and current OSS. To assess whether the difference (change) in EQ-VAS varied between the diagnostic groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used (the results are only given in the text). A multiple logistic regression model was used to compare the odds of obtaining a PASS according to diagnosis, adjusted for age, sex, revision state, and prosthesis type.

To estimate differences in mean change of the OSS between the different diagnostic groups, a multiple linear regression model with adjustment for prosthesis type, age (≤ 60, 60–70, > 70), sex, and revision state was performed ( and ). In these analyses, AF patients were excluded because they generally had an opposite development with no or limited shoulder problems before the shoulder arthroplasty and more problems after the procedure. Inclusion of this group would affect the results and obscure comparison of the other 3 diagnostic groups. The results for AF patients are presented in and as crude means.

Table 3. Crude mean (SD) preoperative and current OSS and EQ-5D, and mean change in OSS and EQ-5D, according to diagnosis

Table 4. Difference in change from preoperative Oxford shoulder score (OSS) to postoperative OSS by diagnosis and prosthesis type, adjusted for sex, age, and revision status

Table 5. Preoperative OSS, current OSS, and change in OSS, divided into pain and function scores, for patients with the four major diagnoses

Results

Pain and function measured by the OSS

Preoperative pain and function, as measured by the OSS, was similar for patients with OA and FS, and somewhat worse for the RA patients, while a high preoperative OSS was seen in AF patients (). The end-result in terms of mean current OSS was more similar for the 4 diagnostic groups, but lowest in the sequelae group and highest in OA patients. Crude mean change in OSS from before the primary operation until the time of receiving the questionnaire was 15 units for RA, 15 for OA, 10 for FS, and –11 for AF, and for all groups the change in OSS was clinically significant (> 4.5 units) and statistically significant (p < 0.001) ().

In the adjusted analysis, patients with RA and OA had the best results in terms of the greatest improvement in OSS, compared to FS patients whose mean change in OSS was 4.4 units less (p = 0.001) (). Furthermore, better results were obtained using conventional and reversed total prostheses than using hemiprostheses ().

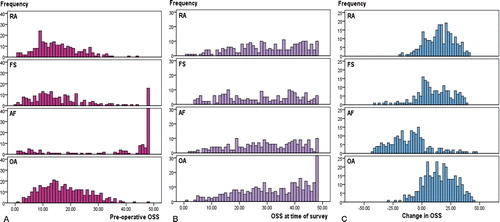

In RA, FS, and OA, the preoperative OSS scores were clustered in the lower region corresponding to seriously impaired function (). Conversely, 140 of the AF patients (57%) scored 48 out of 48 in the preoperative score. Similar plots for the change in OSS were seen for OA and RA patients while the majority of AF patients had a negative change (). A negative change in OSS was seen in 12% of OA patients, 9% of RA patients, and 17% of FS patients.

Figure. Distribution of preoperative OSS (A), current OSS (B), and change in OSS (C) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), fracture sequelae (FS), acute fracture (AF), and osteoarthritis (OA). The number of patients with a preoperative OSS of 48 (the best possible score) in the AF group was 140 and the number with a current OSS of 48 in the OA group was 40.

Patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS)

The percentage of patients reporting a PASS preoperatively was 3 for RA patients, 5 for OA patients, 13 for FS patients, and 80 for AF patients. At the time of the study, 47% of RA patients, 53% of OA patients, 41% of FS patients, and 42% of AF patients were in PASS. In the logistic regression analysis, no statistically significant difference in the odds of being in PASS postoperatively was identified between the 4 diagnostic groups (OR = 0.8, 95% CI: 0.6–1.3 for FS; OR = 1.1, CI: 0.7–1.6 for AF; and OR = 1.1, CI: 0.8–1.7 for OA, all compared to RA).

Pain and function evaluated separately

Patients with RA, OA, and FS scored very low on pain (i.e. high degree of reported pain) prior to the operation with a mean preoperative OSS pain score of about one quarter of a possible 16. The preoperative OSS function scores for these patient groups were 12–14 of 32 possible. The improvement appears to have been more pronounced for pain than for function, with more than a doubling of the OSS pain score and less than a doubling of the OSS function score. Even so, the improvement was statistically significant for both pain and function in RA, OA, and FS patients (p < 0.001, paired-samples t-test; not shown in ). For both pain and function, the improvement was smaller for patients with FS than for RA patients. Patients with AF had the opposite development, going from almost healthy shoulders to damaged ones. The end results in terms of pain and function in AF patients were, however, in the same range as for the other patient groups ().

Quality of life

The preoperative quality of life as measured by the EQ-5D was similar and rather low for patients with RA and OA. For FS patients, a tendency of a higher preoperative life quality was seen. The end results were, however, identical for RA, FS, and AF, while they were better in the OA group. The EQ-5D improved by about 0.25 in the RA and OA groups, while the improvement was smaller in the FS group (0.16) and a worsening in quality of life was seen in the AF group, although the end-result was equal to that in FS and RA patients (). Similarly, an improvement of about 20 units in the EQ-VAS was seen in patients with RA and OA, while for the FS group the change was only 10 units (p < 0.001).

Patients with revisions

The mean change in OSS in patients who had undergone revision surgery was 7, as compared to 14 for those without revision (p < 0.001; AF patients excluded). Furthermore, the mean change in EQ-5D was higher in patients who were never revised than in those who were revised, 0.24 vs. 0.14 (p = 0.02). Finally, the odds ratio for obtaining PASS was 3 for patients who had never been revised compared to those who had (CI: 2–6).

Discussion

The major finding of the present study was that of good results in terms of function, pain, and quality of life after shoulder arthroplasty for patients with OA and RA. The improvement in shoulder function and pain as measured by the OSS was both statistically and clinically significant. Previous studies of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA and OA have similarly found improvement in function and pain (Norris and Iannotti Citation2002, Deshmukh et al. Citation2005, Haines et al. Citation2006, Sperling et al. Citation2007, Raiss et al. Citation2008, Foruria et al. Citation2010, Ekelund and Nyberg Citation2011).

Less encouraging results have been reported in FS patients (Boileau et al. Citation2001, Haines et al. Citation2006). In our study, OSS improved in FS patients, but to a lesser degree than for patients with OA and RA, and the end results were somewhat inferior to those for OA and RA. However, as shoulders with fracture sequelae are very often badly damaged both with respect to the shoulder joint and the rotator cuff, the results in these patients may be considered satisfactory. We have previously shown that FS patients have the worst outcome in terms of implant survival (Fevang et al. Citation2009). On the other hand, patients with AFs had OSS end results that were as good as those for RA patients and they have been shown to have the lowest risk of revision (Fevang et al. Citation2009).

Interestingly, the improvement in function was almost as good as for pain, while the indication for surgery is most often pain. The improved function may be due to less pain, but even so, the finding of good functional results should be considered when evaluating the indication for shoulder arthroplasty.

To gain a better understanding of the OSS results, the scores were dichotomized according to a cut-off value (PASS) obtained from a recent study (Christie et al. Citation2011). Using this cut-off value, 40–50% of our patients were defined to be in PASS in 2010 (at the time of filling in the questionnaires). This was a vast improvement for RA and OA patients in particular (i.e. from 5% to 50% for OA patients), but also for FS patients. A higher percentage of patients in PASS might have been found if the patients had been assessed earlier (i.e. at 1 year postoperatively) and if patients with revisions had been excluded. Even so, the rather large group that did not achieve PASS indicates that although a substantial improvement is obtained, the end-result may still not be completely satisfactory.

Impairment in the general health status, as measured by the preoperative EQ-5D, was seen in patients with a preoperative shoulder disease (OA, RA, or FS). It has been shown that general health perception scores decrease steadily after the age of 50 (Boorman et al. Citation2003). Even so, patients with acute fractures who were older than the other patients reported markedly better scores on preoperative EQ-5D than those in the other 3 groups. This shows that the shoulder arthropathy causing the shoulder operation had substantial effects on several aspects of life quality. This was further illustrated by the finding of a substantial improvement in EQ-5D after surgery. Similar findings have been described in patients with shoulder osteoarthritis (Lo et al. Citation2005), and Boorman et al. (Citation2003) described similar improvement in health status for shoulder arthroplasty as for hip arthroplasty. A recent study showed comparable improvements in EQ-5D after hip arthroplasty and knee arthroplasty (0.31 and 0.22, respectively) to what we found after shoulder arthroplasty (Jansson and Granath Citation2011).

The improvement in EQ-5D was markedly lower for the FS group, and this probably reflects the higher preoperative score in this group. RA is a systemic disease that affects general health status, but why the OA patients had a lower preoperative life quality than FS patients is less obvious. Some OA patients may have impaired quality of life because of polyarticular disease, and others because of comorbidity associated with a high BMI—which is a risk factor for osteoarthritis. With a better preoperative status in the FS group, superior end results would be expected in this group. That this is not the case strengthens the impression of less favorable results after shoulder arthroplasty for this indication.

Another important finding was that total prostheses had better results than hemiprostheses in terms of pain and function (OSS). Similar findings were reported in 2 review articles comparing hemiprostheses and total prostheses (Bryant et al. Citation2005, Radnay et al. Citation2007). Our results support the increasing use of total prostheses currently taking place in Norway. The major interest of our study was not prosthesis type. A detailed analysis of pain and function according to prosthesis type will be part of our next study.

Strengths and weaknesses

A weakness of our study was the response rate of 65%. The non-responders differed from the responders in that there were more women who were older, and they more often had AFs. Although we cannot know whether the results in the non-responder group would have differed from those of the responders, the similar revision rates in the groups suggest that there were no large differences in results between the responders and the non-responders. Even so, the proportion of hemiprostheses in the non-responder group was higher and the indication for revision may be different for hemiprostheses than for total prostheses. Thus, a similar revision rate may not fully ensure a lack of difference in results between non-responders and responders. The retrospective collection of preoperative scores was another weakness of our study. However, it has been shown that in larger groups of people, there is no statistically significant nor clinically relevant difference between a recollected OSS score and a contemporary score—although it was found that there was a slight tendency to overestimate the symptoms when remembering them (Wilson et al. Citation2009). We believe that the consistency of our results confirms this, as shown, for example, by the similarity of preoperative scores for RA and OA patients and by the correlation of EQ-5D and OSS results (i.e. with RA scoring being worst for all preoperative parameters; ).

A major strength of our study was the very large study population, which allowed comparison of different diagnostic groups and adjustment for possible confounders. To our knowledge, there have been no studies assessing function, pain, and quality of life after shoulder replacement in such a large study population. Also, our study was based on national registry data—which means that the study population was from a real-life setting. Thus, we contacted and included patients who had been operated at all types of hospitals, and there was a large spectrum of implants.

Conclusion

Good results in terms of improved pain, function, and quality of life were observed after shoulder arthroplasty for patients with RA, OA, and FS—although somewhat inferior results were seen in the group with sequelae. AF patients had as good end results as the other diagnostic groups. Shoulder function improved almost as much as pain. A shoulder arthropathy has a major effect on life quality, and treatment with shoulder replacement not only improves shoulder function and reduces pain in the shoulder, but it also significantly improves quality of life.

BTSF had full access to the data and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. Conception and design: BTSF, SHLL, GB, AS, LIH, OF. Acquisition of data: BTSF, SHLL, GB, OF. Analysis and interpretation of data: BTSF, SHLL, LIH, OF. Drafting of manuscript: BTSF. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Final approval of the submitted version: all authors.

We thank the Norwegian surgeons for delivering data to the NAR and we thank the patients for taking the time and trouble to answer the questionnaire. Furthermore, we are grateful to all the secretaries and other co-workers at the NAR for help in the process of distributing and collecting questionnaires.

No competing interests declared.

- Boileau P, Trojani C, Walch G, Krishnan SG, Romeo A, Sinnerton R. Shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of the sequelae of fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2001; 10 (4): 299-308.

- Boileau P, Avidor C, Krishnan SG, Walch G, Kempf JF, Mole D. Cemented polyethylene versus uncemented metal-backed glenoid components in total shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective, double-blind, randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11 (4): 351-9.

- Boorman RS, Kopjar B, Fehringer E, Churchill RS, Smith K, Matsen FA, 3rd. The effect of total shoulder arthroplasty on self-assessed health status is comparable to that of total hip arthroplasty and coronary artery bypass grafting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12 (2): 158-63.

- Bryant D, Litchfield R, Sandow M, Gartsman GM, Guyatt G, Kirkley A. A comparison of pain, strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis of the shoulder. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 87 (9): 1947-56.

- Christie A, Hagen KB, Mowinckel P, Dagfinrud H. Methodological properties of six shoulder disability measures in patients with rheumatic diseases referred for shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18 (1): 89-95.

- Christie A, Dagfinrud H, Garratt AM, Ringen Osnes H, Hagen KB. Identification of shoulder-specific patient acceptable symptom state in patients with rheumatic diseases undergoing shoulder surgery. J Hand Ther 2011; 24 (1): 53-60; quiz 61.

- Cloke DJ, Lynn SE, Watson H, Steen IN, Purdy S, Williams JR. A comparison of functional, patient-based scores in subacromial impingement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14 (4): 380-4.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78 (4): 593-600.

- Desai AS, Dramis A, Hearnden AJ. Critical appraisal of subjective outcome measures used in the assessment of shoulder disability. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010; 92 (1): 9-13.

- Deshmukh AV, Koris M, Zurakowski D, Thornhill TS. Total shoulder arthroplasty: long-term survivorship, functional outcome, and quality of life. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14 (5): 471-9.

- Ekelund A, Nyberg R. Can reverse shoulder arthroplasty be used with few complications in rheumatoid arthritis?. Clin Orthop 2011;469(9): 2483-8.

- Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen A, Furnes O. Risk factors for revision after shoulder arthroplasty: 1,825 shoulder arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2009; 80(1):83-91.

- Flinkkila T, Ristiniemi J, Lakovaara M, Hyvonen P, Leppilahti J. Hook-plate fixation of unstable lateral clavicle fractures: a report on 63 patients. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (4): 644-9.

- Foruria AM, Sperling JW, Ankem HK, Oh LS, Cofield RH. Total shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis in patients 80 years of age and older. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010; 92 (7): 970-4.

- Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2000; 82 (1): 26-34.

- Haines JF, Trail IA, Nuttall D, Birch A, Barrow A. The results of arthroplasty in osteoarthritis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88 (4): 496-501.

- Jansson KA, Granath F. Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) before and after orthopedic surgery. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (1): 82-9.

- Kircher J, Wiedemann M, Magosch P, Lichtenberg S, Habermeyer P. Improved accuracy of glenoid positioning in total shoulder arthroplasty with intraoperative navigation: a prospective-randomized clinical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18 (4): 515-20.

- Lo IK, Litchfield RB, Griffin S, Faber K, Patterson SD, Kirkley A. Quality-of-life outcome following hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 87 (10): 2178-85.

- Murray DW, Frost SJ. Pain in the assessment of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1998; 80 (3): 426-31.

- Norris TR, Iannotti JP. Functional outcome after shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: a multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11 (2): 130-5.

- Radnay CS, Setter KJ, Chambers L, Levine WN, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS. Total shoulder replacement compared with humeral head replacement for the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16 (4): 396-402.

- Rahme H, Mattsson P, Wikblad L, Nowak J, Larsson S. Stability of cemented in-line pegged glenoid compared with keeled glenoid components in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91 (8): 1965-72.

- Raiss P, Aldinger PR, Kasten P, Rickert M, Loew M. Total shoulder replacement in young and middle-aged patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (6): 764-9.

- Rees JL, Dawson J, Hand GC, Cooper C, Judge A, Price AJ, Beard DJ, Carr AJ. The use of patient-reported outcome measures and patient satisfaction ratings to assess outcome in hemiarthroplasty of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010; 92 (8): 1107-11.

- Robinson CM, Page RS, Hill RM, Sanders DL, Court-Brown CM, Wakefield AE. Primary hemiarthroplasty for treatment of proximal humeral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 85 (7): 1215-23.

- Rosenberg N, Soudry M. Shoulder impairment following treatment of diaphysial fractures of humerus by functional brace. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2006; 126 (7): 437-40.

- Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS. Total shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis of the shoulder: results of 303 consecutive cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16 (6): 683-90.

- Trail IA, Nuttall D. The results of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002; 84 (8): 1121-5.

- Tubach F, Pham T, Skomsvoll JF, Mikkelsen K, Bjorneboe O, Ravaud P, Dougados M, Kvien TK. Stability of the patient acceptable symptomatic state over time in outcome criteria in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 55 (6): 960-3.

- Wilson J, Baker P, Rangan A. Is retrospective application of the Oxford Shoulder Score valid? J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18 (4): 577-80.