Abstract

Background and purpose Although a tourniquet may reduce bleeding during total knee replacement (TKA), and thereby possibly improve fixation, it might also cause complications. Migration as measured by radiostereometric analysis (RSA) can predict future loosening. We investigated whether the use of a tourniquet influences prosthesis fixation measured with RSA. This has not been investigated previously to our knowledge.

Methods 50 patients with osteoarthritis of the knee were randomized to cemented TKA with or without tourniquet. RSA was performed postoperatively and at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years. Pain during hospital stay was registered with a visual analog scale (VAS) and morphine consumption was measured. Overt bleeding and blood transfusions were registered, and total bleeding was estimated by the hemoglobin dilution method. Range of motion was measured up to 2 years.

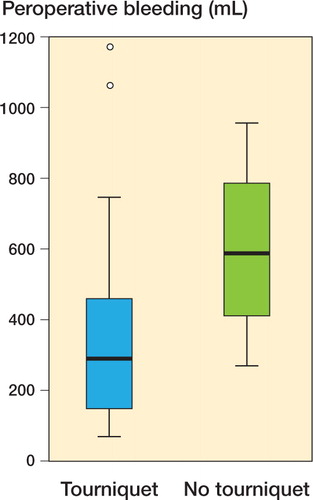

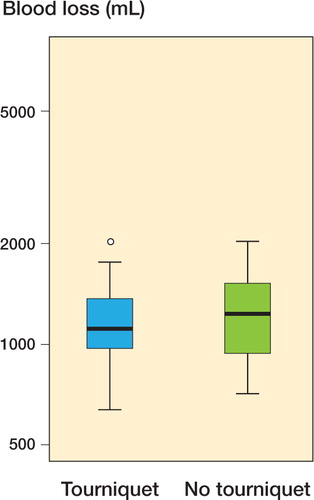

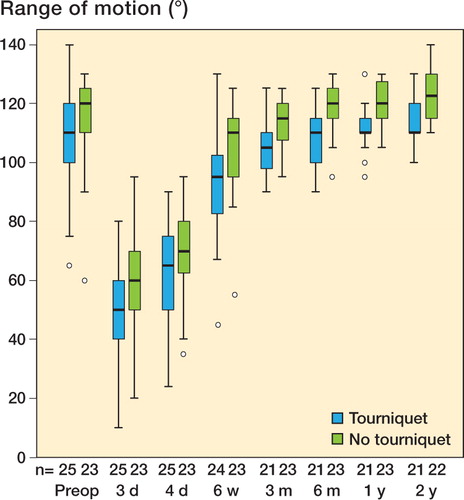

Results RSA maximal total point motion (MTPM) differed by 0.01 mm (95% CI –0.13 to 0.15). Patients in the tourniquet group had less overt bleeding (317 mL vs. 615 mL), but the total bleeding estimated by hemoglobin dilution at day 4 was only slightly less (1,184 mL vs. 1,236 mL) with a mean difference of –54 mL (95% CI –256 to 152). Pain VAS measurements were lower in the non-tourniquet group (p = 0.01). There was no significant difference in morphine consumption. Range of motion was 11° more in the non-tourniquet group (p = 0.001 at 2 years).

Interpretation Tourniquet use did not improve fixation but it may cause more postoperative pain and less range of motion.

The use of a tourniquet during total knee replacement (TKA) is routine at many departments. It is believed to facilitate dissection and reduce peroperative bleeding, but the main argument for its use is that bleeding bone surfaces might impair the fixation of cemented prostheses, due to less cement penetration (Alcelik et al. Citation2011).

On the other hand, a tourniquet is associated with reperfusion trauma and oxidative stress. There is also a risk of injury due to pressure on skin, muscle, nerves, and arteriosclerotic vessels, and a risk of deep vein thrombosis (Newman Citation1984, CitationIrvine and Chan 1986, Silver et al. Citation1986, Abdel-Salam and Eyres Citation1995, Clarke et al. Citation2001, Olivecrona et al. Citation2006). Tourniquets reduce the surgical field, which might jeopardize sterility of the postoperative wound dressing. They are cumbersome to apply, especially in overweight patients. We have had the clinical impression that postoperative pain is to some extent due to the tourniquet.

Because of these drawbacks of tourniquet use, our department stopped using tourniquets in 2003. After a short learning period, we perceived this to be more practical and to be associated with less postoperative pain. To our knowledge, a positive effect of tourniquet use on implant fixation has never been shown. However, this possibility meant that our new routine should be evaluated in a trial.

Radiostereometric analysis is performed to measure early postoperative migration. It is generally believed that there is an association between early migration and the risk of late loosening (Nilsson and Karrholm Citation1996). This has been supported by one study (Ryd et al. Citation1995), and by theoretical reasoning. Thus, if a relevant difference in early migration between patients operated with or without a tourniquet could be excluded, it would be reasonable to assume that tourniquet use is not related to the quality of the fixation. No RSA data on the effect of tourniquet use are available in the literature.

We performed a randomized controlled trial with blind evaluation to study the effects of tourniquet use. We used migration by RSA as the primary effect variable.

Patients and methods

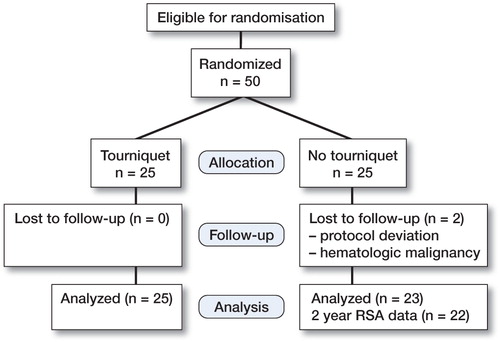

Patients ()

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Linköping, reference number 2006/59-31. We included 50 patients (30 women) from the county of Östergötland, Sweden, who were on the waiting list for elective primary total knee surgery due to osteoarthritis. Sample size was estimated from a maximum total point motion (MTPM) mean difference of 0.2 mm with SD of 0.2 (95% CI and 80% power), which were considered relevant based on an earlier study (Hilding et. al Citation2000).

All patients () were operated in Motala, Sweden. Inclusion criteria were primary or secondary osteoarthritis without other severe disease (ASA 1–2). Exclusion criteria were inability to give informed consent, rheumatic arthritis, malignancy, coagulation disorder or medical treatment influencing the coagulation, liver disease, severe heart disease, or bilateral operation. The patients who declined to participate in the study were not registered.

Table 1. Patient characteristi

Patients were allocated to treatment groups immediately before surgery by opening a sealed envelope. Randomization was stratified for sex and performed in blocks. Patients were not informed about tourniquet use, and care was taken not to disclose treatment allocation. The trial was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Surgery

The operations were performed between June 2007 and April 2009 by HL in 34 cases and by 2 other surgeons in 15 cases. All operations were done under spinal anesthesia. We used the Nexgen CR all-poly tibia knee prosthesis (Zimmer), inserted after pulsed lavage, and cemented with Palacos R+G (Heraeus Medical Nordic, Sollentuna, Sweden) (40 g Palacos and 0.5 g gentamicin). 2 g cloxacillin was given intravenously just before and 3 times after the operation. Low–molecular-weight heparin (Innohep, 4,500 IE subcutaneously) was used for the first 14 postoperative days.

For RSA measurements, altogether 12 tantalum beads (0.8–1 mm) were inserted in the all-poly tibial component and the tibial bone metaphysis. We used a standard tourniquet (Stille AB, Solna, Sweden) 110 mm wide, which was inflated to 275 mmHg during the entire operation if the patient was randomized to tourniquet use. Postoperative paracetamol and morphine analogs were given according to a standard protocol for pain management, with addition of extra morphine analogs on demand.

Evaluation

The radiostereometric X-ray examinations were performed 3 days after surgery, and after 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years. The blind analysis of the RSA data was done using the UmRSA computer program (RSA Biomedical AB, Umeå, Sweden). Pain was assessed by visual analog scale (VAS) at 8 time points during the hospital stay (at 0800 h, 1400 h, and 2000 h on the first 2 postoperative days and at 0800 h and 1400 h on the third postoperative day). The mean value of all these VAS values was used for analysis. ROM was measured before surgery and after 3 days, 4 days, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years. These measurements were performed by a physiotherapist who did not know whether a tourniquet had been used. Blood loss was measured during surgery by weighing the surgical sponges and by subtracting the amount of irrigation fluid used from the content of the suction drain. Postoperative overt bleeding volume (in the drains) was estimated by measuring the hemoglobin content of the drains in relation to the blood hemoglobin concentration. Total blood loss was estimated by the hemoglobin dilution method (Lisander et al. Citation1998) based on blood volume according to (Nadler et al. Citation1962). Postoperative use of morphine-analog drugs was described as morphine equivalents for the 4 first days (including the day of surgery).

Statistics

The primary effect variable was migration measured by RSA (MTPM) after 2 years. Secondary effect variables were other RSA outcomes, pain assessment during hospital stay, range of movement up to 2 years after surgery, and blood loss.

Because the RSA MTPM values were far from normally distributed, we used the Mann-Whitney test and calculated a non-parametric confidence interval for the difference between group medians using the Hodges-Lehmann estimate (SPSS 19.0 software). Pain was analyzed as the sum of measurements as described above, using the Mann-Whitney test.

Bleeding, morphine consumption, and range of motion appeared normally distributed and were analyzed with Student’s t-test. The 2-year result was regarded as final, and is given more emphasis. The gain in range of motion (from preoperatively to 2 years postoperatively) was dependent on range of motion before surgery, and was therefore analyzed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using preoperative range of motion as covariate.

Results

Primary variable

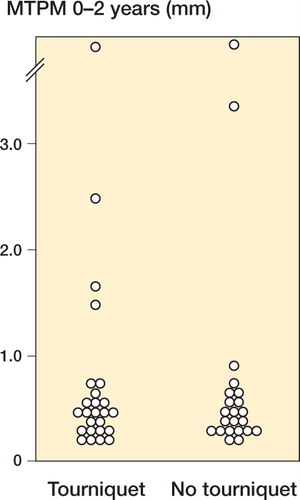

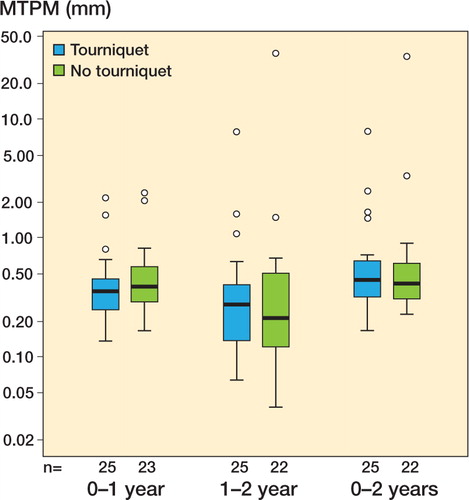

MTPM at 2 years showed a skewed distribution, with a few patients having considerable migration (). There was no statistically significant group difference, and the non-parametric 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference between group medians ranged from – 0.13 to 0.15 mm (). The number of outliers, defined as having a 2-year MTPM of more than 1 mm, was 4 for the tourniquet group and 2 for the non-tourniquet group.

Secondary variables

None of the other RSA variables at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years (x-, y-, and z-translation and rotation) showed a statistically significant difference ().

Table 2. RSA variables at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years (x–, y–, z–translation and rotation). No variables showed a significant difference

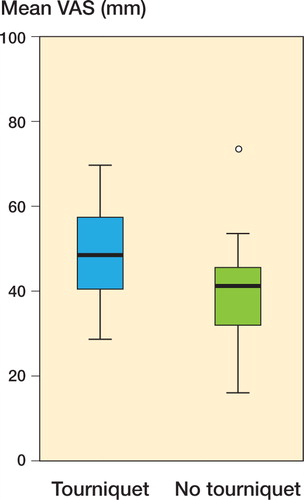

VAS Pain values during the first 4 days were higher in the tourniquet group (median 49 vs. 41 mm; p = 0.01) (). Non-parametric 95% CIs for the difference between group medians ranged from 2.5 to 15.

Total overt bleeding was less in the tourniquet group (317 vs. 615 mL; p = 0.002) (). 4 patients in the tourniquet group and 3 in the non-tourniquet group needed blood transfusions. As estimated by the hemoglobin dilution method, the total blood loss was 1,184 (SD 346) mL in the tourniquet group and 1,236 (SD 349) mL in the non-tourniquet group (95% CI for the difference between means: –256 to 152 mL).

Morphine consumption did not show any statistically significant group difference. The 95% CI for the difference between means (tourniquet minus no tourniquet) ranged from –31 to 18 mg morphine equivalents. This should be related to the average total use of 218 mg.

1 patient in the tourniquet group needed mobilization under anesthesia at 6 weeks, and range of motion was not measured thereafter. Complete data for range of motion were available for 21 patients in the tourniquet group and 22 patients in the non-tourniquet group. Range of motion, expressed as a sum of all measurements, was less in the tourniquet group (p = 0.01). The range of motion at 2 years was still less in the tourniquet group (tourniquet: mean 113°; non-tourniquet: mean 124°; 95% CI for difference between means: 5–17°; p = 0.001) (). Patients with a small range of motion preoperatively had gained more in range at 2 years. The gain, after correction for preoperative status, was dependent on tourniquet treatment. This gain was statistically significant after correction for preoperative range of motion (p = 0.001, ANCOVA).

Clinical results

Mean operating time was 85 (SD 30) min for the tourniquet group and 81 (SD 23) min for the non-tourniquet group. Mean hospital stay was 4.9 and 4.5 days, respectively. 2 patients in the non-tourniquet group were excluded from analysis, 1 patient because of deviation from the protocol during surgery and afterwards (femoral nerve block, no drain) and 1 patient because of a hematological malignancy. She was in remission at the time of inclusion, but had a relapse requiring cytostatic treatment. The RSA data were complete for all remaining patients except one at the 2-year follow-up (no tourniquet) ().

After the study period, 1 patient in the non-tourniquet group had his prosthesis revised because of loosening. This patient showed gross migration already at 1 year. 1 patient in the tourniquet group also showed gross migration, but at the time of writing there have been no clinical symptoms of loosening.

Discussion

Our RSA data do not support the view that tourniquet use will improve fixation. We found no statistically significant effect on prosthesis migration. The confidence interval excludes an increase in median value of 0.13 mm if a tourniquet is not used. Such a small difference is not likely to have any clinical importance. However, the distribution of the migration values was far from normal, and there were a number of outliers. These outliers are probably patients who may be at risk of future loosening (and one of these has already undergone revision). Indeed, RSA data may often show discontinuous distributions, reflecting distinct subcategories of the postoperative course (some are well fixed and others not) (Aspenberg et al. Citation2008). In this study, there were similar numbers of outliers in both groups.

Apart from prosthesis fixation, bleeding is generally considered to be a good reason for tourniquet use. However, the possible advantage of less bleeding should be balanced against the disadvantage of increased postoperative pain and a smaller final range of motion. We found a reduction in overt bleeding in the tourniquet group, as has been described in a recent meta-analysis (Alcelik et al. Citation2011). However, there was no substantial difference in total bleeding as estimated by the hemoglobin dilution method, and any increase exceeding 22% from lack of tourniquet use could be excluded with 95% confidence. It is conceivable that the hidden, postsurgical blood loss is less in patients in whom the surgeons have been able to identify and cauterize bleeding vessels.

The main reasons for refraining from tourniquet use, as judged by our results, are postoperative pain and range of motion. Before the study, we had the impression of a clear reduction in the patients’ complaints about thigh pain after we stopped using a tourniquet. Although patients reported more pain in the tourniquet group, there was no statistically significant difference in the use of morphine-analog analgesics. This may reflect that the difference between the groups was only minor, so that most patients’ pain was controlled by standard postoperative analgesics given to all patients. The range of motion may be more important: the difference between 113° and 124° may mean the difference between being able to ride a bicycle or not. There have been very few previous randomized trials on tourniquet use and range of motion. Short-term better flexion has been shown in 2 studies (Abdel-Salam and Eyres Citation1995, Wakankar et al. Citation1999), but neither publication reported a difference between treatment groups in the longer term. Total range of motion was not reported.

The mechanism behind the reduced range of motion is unclear. However, the postoperative thigh pain might reflect muscle injury due to physical damage, as well as reperfusion injury, which might both cause a degree of muscle fibrosis. The increased pain might also reduce the patient’s ability to perform postoperative training, which has been shown to negatively affect the final range of motion (Newman Citation1984, Silver et al. Citation1986, Clarke et al. Citation2001).

The main weaknesses of our study lie in the limitations of the RSA method to predict clinical outcomes, in spite of the fact that RSA studies are recommended before new joint prosthesis are commercially deployed (Derbyshire et al. Citation2009). The study size is sufficient for construction of relevant confidence intervals, but not for analysis of the number of outliers in the respective groups. This must be considered. The findings regarding range of motion and pain—although highly statistically significant—should be interpreted with caution, as they were not primary variables. Estimates of bleeding have a high degree of uncertainty, as the number of patients may be too small.

In conclusion, our RSA data do not support the use of a tourniquet to improve fixation. On the contrary, tourniquets appear to cause more postoperative pain and less range of motion.

HL: design, data collection, analysis, statistics, and writing. PA: analysis, statistics, and writing. LG: design and analysis.

We thank Carmen Henriksson, Susanne Lundgren, and Ulf Kallander for technical assistance. The study was funded by Swedish Research Council (VR - 2009-6725).

No competing interests declared.

- Abdel-Salam A, Eyres KS. Effects of tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty. A prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint surg (Br) 1995; 77 (2): 250-3.

- Alcelik I, Pollock RD, Sukeik M, Bettany-Saltikov J, Armstrong PM, Fismer PA. Comparison of outcomes with and without a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty 2011; 27 (3): 331-40.

- Aspenberg P, Wagner P, Nilsson KG, Ranstam J . Fixed or loose? Dichotomy in rsa data for cemented cups. Acta Orthop 2008 ; 79 (4): 467-73.

- Clarke MT, Longstaff L, Edwards D, Rushton N.Tourniquet-induced wound hypoxia after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001; 83 (1): 40-4.

- Derbyshire B, Prescott RJ, Porter M L . Notes on the use and interpretation of radiostereometric analysis. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (1): 124-30.

- Hilding M, Ryd L, Toksvig-Larsen S, Aspenberg P. Clodronate prevents prosthetic migration: A randomized radiostereometric study of 50 total knee atients. Acta Orthop 2000; 71 (6): 553-7.

- Irvine GB, Chan RN. Arterial calcification and tourniquets. Lancet 1986; 328:8517-1217.

- Lisander B, Ivarsson I, Jacobsson S A . Intraoperative autotransfusion is associated with modest reduction of allogeneic transfusion in prosthetic hip surgery. Acta Anaesth 1998; 42 (6): 707-12.

- Nadler SB, Hidalgo JH, Bloch T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery 1962; 51 (2): 224-32.

- Newman RJ.Metabolic effects of tourniquet ischaemia studied by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1984; 66 (3): 434-40.

- Nilsson KG, Karrholm J. Rsa in the assessment of aseptic loosening. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78 (1): 1-3.

- Olivecrona C, Tidermark J, Hamberg P, Ponzer S, Cederfjall C. Skin protection underneath the pneumatic tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial of 92 patients. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (3): 519-23.

- Ryd L, Albrektsson BE, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, . Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995; 77 (3): 377-83.

- Silver R, de la Garza J, Rang MKoreska J. Limb swelling after release of a tourniquet. Clin Orthop 1986; (206): 86-9.

- Wakankar HM, Nicholl JE, Koka R, D’Arcy JC. The tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty. A prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81 (1): 30-3.