Abstract

Background and purpose Treatment options for failed internal fixation of hip fractures include prosthetic replacement. We evaluated survival, complications, and radiographic outcome in 30 patients who were operated with a specific modular, uncemented hip reconstruction prosthesis as a salvage procedure after failed treatment of trochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures.

Patients and methods We used data from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register and journal files to analyze complications and survival. Initially, a high proportion of trochanteric fractures (7/10) were classified as unstable and 12 of 20 subtrochanteric fractures had an extension through the greater trochanter. Modes of failure after primary internal fixation were cutout (n = 12), migration of the femoral neck screw (n = 9), and other (n = 9).

Results Mean age at the index operation with the modular prosthesis was 77 (52–93) years and the mean follow-up was 4 (1–9) years. Union of the remaining fracture fragments was observed in 26 hips, restoration of proximal bone defects in 16 hips, and bone ingrowth of the stem in 25 hips. Subsidence was evident in 4 cases. 1 patient was revised by component exchange because of recurrent dislocation, and another 6 patients were reoperated: 5 because of deep infections and 1 because of periprosthetic fracture. The cumulative 3-year survival for revision was 96% (95% CI: 89–100) and for any reoperation it was 83% (68–93).

Interpretation The modular stem allowed fixation distal to the fracture system. Radiographic outcome was good. The rate of complications, however—especially infections—was high. We believe that preoperative laboratory screening for low-grade infection and synovial cultures could contribute to better treatment in some of these patients.

The failure rate after surgery for extracapsular hip fractures is low. Occasionally, cutout and migration of the femoral neck screw occur regardless of whether a sliding hip screw or an intramedullary nail is used (Stern Citation2007). Implant failure after open or closed reduction and internal fixation is mostly seen in patients with unstable fracture patterns, poor bone quality, or poor positioning of the internal fixation device (Haidukewych et al. Citation2001).

It is often difficult to find straightforward solutions. For younger patients, a second attempt at osteosynthesis with or without bone grafting may be favored. For elderly patients, prosthetic replacement is attractive, allowing immediate ambulation without fear of further fracture complications (Stern Citation2007).

A salvage procedure converting failed internal fixation to a cemented primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) is challenging due to pre-existing and acquired osteoporosis, deformation of the trochanteric region, and difficulties in obtaining cement pressurization because of cortical screw holes (Zhang et al. Citation2004). Thus, an uncemented hip revision arthroplasty in these cases would appear attractive. These implants are designed to bypass regions of proximally deficient bone and to obtain stability and fixation in the distal femoral bone where there is good bone stock.

There have been few reports on salvage THA with modular revision implants, and the numbers of patients have been limited (n = 10–23) (Laffosse et al. Citation2007, Talmo and Bono Citation2008, D’Arrigo et al. Citation2010, Abouelela Citation2011, Thakur et al. Citation2011). We reviewed a series of patients who had been operated with a specific modular, uncemented hip revision arthroplasty for failure of internal fixation of trochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures.

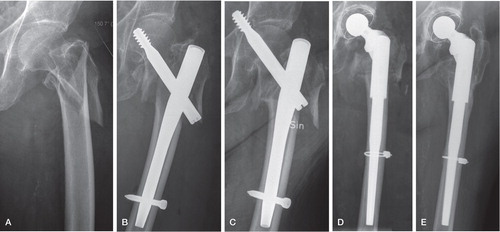

A subtrochanteric fracture treated with internal fixation (A and B). Due to migration of the screw into the pelvis (C), a THA was performed 1.5 months after the first operation (D). 1 year after the index operation, the subtrochanteric fracture appeared to have healed without any major subsidence of the stem (E).

Patients and methods

Source of data

All public and private orthopedic units in Sweden that perform THA report to the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Apart from the information included in the social security number (date of birth and sex), individual data on diagnoses and detailed information on implants and fixation are reported. Individual procedure registration captures between 97% and 99% of all primary procedures (Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Citation2009).

We identified 50 patients in the Register who had been operated with the MP hip reconstruction prosthesis (Waldemar Link, Germany). The MP stem was used in all patients as a primary THA in a salvage procedure after failed internal fixation of trochanteric or subtrochanteric femur fractures. All journal files and radiographs were examined. We excluded patients who had had a radiographic follow-up of less than 6 months (n = 17) and also 3 patients with pathological fractures. This left us with a final study cohort of 30 patients (27 females) who had been operated during the period 2002–2009 in one of 12 orthopedic units.

The regional ethics review board approved the study (D no. 2010/1584-31/1).

Implant

The MP prosthesis consists of a proximal segment (neck segment) and a distal segment (stem) with a 70-μm microporous surface. The proximal part of the stem comprises the modular junction, which is smooth and machined to engage the neck segment, providing variability in neck geometry. The tapered stem has a fluted geometry with a 3° angular bow to accommodate the femoral curvature. The MP prosthesis is impacted into the femoral canal until rigid stability to axial and torsional testing is achieved. Various stem lengths and diameters allow independent fitting of the diaphysis (Weiss et al. Citation2011a).

Patients

There were more patients with subtrochanteric fractures (n = 20) than with trochanteric fractures (n = 10). Most patients were operated with an intramedullary nail (n = 21) followed by a sliding hip screw device (n = 7). Modes of failure were dominated by cutout (n = 12) and migration of the femoral neck screw (n = 9) (Figure). The mean interval between the first surgical procedure and the operation with the MP stem was 2 (SD 7) years. 17 patients had 1 surgical procedure and 13 patients 2 or more before the salvage procedure ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the 30 patients

Mean age at the index operation with the MP prosthesis was 77 (52–93) years. The mean follow-up time until the end of the study was 4 (1–9) years. 22 patients were operated with a posterior approach and 8 patients were operated using an anterolateral approach. 24 patients received a cemented cup and 6 an uncemented cup. Cerclage wires were used in 10 patients.

Radiographs

Trochanteric hip fractures were classified according to Jensen-Michaelsen (Jensen Citation1980) and subtrochanteric fractures were classified according to Seinsheimer (Citation1978). In addition, both fracture types were classified according to the AO/OTA classification as type 31-A (subdivided into groups A1–A3) and type 32-A (subdivided into groups A1–B3) (Müller et al. Citation1987, OTA Citation1996). Radiographs obtained immediately after the operation with the MP prosthesis were compared with those at follow-up examination. Bone remodeling of the proximal femur was classified subjectively as increasing defects, no change, or osseous restoration (Bohm and Bischel Citation2001). Fixation of the uncemented stem was evaluated according to the criteria of Engh et al. (Citation1990) and was classified as “bone ingrowth”, “stable fibrous”, or “unstable”. Vertical femoral migration of the implant was measured from fixed points on the prosthesis to any reproducible fixed landmark on the femur. These points included the lesser trochanter, the tip of the greater trochanter, screw holes, or trochanteric wires (Engh et al. Citation1990). Distal migration of the femoral component of more than 5 mm was defined as subsidence (Sporer and Paprosky Citation2004). Heterotopic ossification was classified using the grading system of Brooker et al. (Citation1973). All radiographs were assessed digitally by a senior radiologist (MB) using Sectra PACS software IDS5 (Sectra-Imtec AB, Linköping, Sweden). The geometry of the radiographs was calibrated to the known diameter of the prosthesis head and/or the femoral stem.

Statistics

Quantitative results are reported as mean (SD). Life tables and survival functions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The term “reoperation” included all types of new surgical procedures in the same hip following the index operation. The term “revision” was defined as an intervention where 1 or more components of the prosthesis were exchanged or where the entire prosthesis was removed. All statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics version 18 for Windows.

Results

Radiographs

Radiographs obtained immediately after the trauma showed that 7 of 10 trochanteric fractures were classified as unstable according to Jensen-Michaelsen. 12 of the 20 subtrochanteric fractures had an extension through the greater trochanter (Seinsheimer Citation1978) ().

After the index operation with the MP stem, union of the remaining fracture fragments was observed in 26 of the 30 cases. Restoration of proximal bone defects was noted in 16 hips, bone ingrowth of the MP stem in 25 hips, and subsidence in 4 stems. 14 cases showed heterotopic ossifications of varying degrees at the latest follow-up and 7 cases had more ossifications when compared to radiographs taken directly after the index operation ().

Table 2. Radiographic outcome (n = 30)

Revisions, complications, and survival

The cumulative 3-year survival for revision was 96% (CI: 89–100) and for any reoperation it was 83% (CI: 68–93). 1 patient was revised by exchange of the proximal components due to recurrent dislocation. 6 other patients were reoperated (i.e. there was no component exchange of the prosthesis), 5 patients due to deep infection (only soft tissue debridement without removal of implants). The other patient was reoperated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) due to periprosthetic fracture 1 year after the index operation. Apart from the patient who was revised, closed reduction due to dislocation occurred in 2 patients.

Discussion

We evaluated 30 patients who had been operated with a modular revision THA as a salvage procedure after failed hip fractures. Most hips showed fracture union, restoration of proximal bone, bony ingrowth of the uncemented stem, and only limited subsidence. However, 7 patients needed further surgery during follow-up. The cumulative 3-year survival for revision was 96% and for reoperation it was 83%.

Chirodian et al. (Citation2005) reported on the outcome of 1,024 surgical procedures with the sliding hip screw for trochanteric hip fractures. The authors found a complication rate related to the surgical procedure of 4%, with a 2% incidence of cutout of the femoral neck screw. A meta-analysis involving 3,279 extracapsular proximal femoral fractures noted a cutout rate of 2–3% after ORIF (Jones et al. Citation2006). The rate of avascular necrosis in patients operated for trochanteric fractures has been reported to be less than 1% (Bartonicek et al. Citation2007). Overall, the rate of complications after surgical treatment of extracapsular hip fractures is low; however, the total amount of fractures treated is high (Stern Citation2007). Moreover, some authors have documented cutout rates of up to 8% (Simpson et al. Citation1989) and Haidukewych et al. (Citation2001) described a failure of fracture healing or fixation in 15 of 47 patients with problematic fracture patterns.

Salvage procedures include revision internal fixation and prosthetic replacement. In younger patients and active older patients with good remaining bone stock and a well-preserved hip joint, revision internal fixation with bone grafting may be the best choice. With properly selected patients, a high rate of success can be achieved (Haidukewych and Berry Citation2003). Patients with poor bone quality in the proximal femur and/or older patients with lower demands and signs of osteoarthritis may be treated with THA (Haidukewych and Berry Citation2003).

Several reports have documented varying results using conventional hip stems as a salvage procedure (Mehlhoff et al. Citation1991, Haentjens et al. Citation1994, Tabsh et al. Citation1997, Haidukewych and Berry Citation2003, Zhang et al. Citation2004, Hammad et al. Citation2008, Mortazavi et al. Citation2012). Often, the conversion to THA does not allow the use of conventional femoral components for various reasons. Uncemented modular revision implants therefore provide several potential advantages. They allow separate preparation of the proximal and distal bone in the femur to maximize prosthesis fill. In addition, individual adjustment of leg length, offset, and anteversion can be obtained. Modular stems such as the MP Link prosthesis are designed to bypass the regions of proximally deficient bone and achieve stability and fixation in more distal femoral bone (Weiss et al. Citation2011b).

Our radiographic results are satisfactory, and confirm the results of other studies with modular implants (Laffosse et al. Citation2007, Talmo and Bono Citation2008, D’Arrigo et al. Citation2010, Abouelela Citation2011, Thakur et al. Citation2011). Still, we observed more revisions/reoperations in our cohort. Other authors (Talmo and Bono Citation2008, Abouelela Citation2011) only studied patients who had had 1 previous surgical procedure before the index operation, whereas almost half of our patients had undergone at least 2 surgical procedures before their prosthetic replacement, which might have influenced the risk of complications. Moreover, 7 of 10 patients with trochanteric fractures had an unstable fracture pattern and 12 of 20 subtrochanteric fractures included the greater trochanter. Many orthopedic clinics were involved in the surgical treatment of these patients, which may also have influenced the rate of complications.

Deep infection was the major cause of reoperation. This is not surprising, since the patients had undergone previous fracture surgery which failed. A more careful laboratory screening and examination of the clinical history of these patients, concentrating especially on previous wound healing problems and suspicion of postoperative infection, might be of value in these cases. Such patients might benefit from preoperative cultures from the joint, removal of the failed osteosynthesis, and joint debridement in a first session before implantation of the prosthesis. Strict adherence to the timing of antibiotic prophylaxis and a choice of agent(s) with a broader spectrum than that of the commonly used cloxacillin may also reduce the incidence of infections in these high-risk patients.

The weaknesses of our study include the short follow-up and the lack of some clinical data (e.g. pain levels and functional scores). The strength was the use of only 1 design of hip prosthesis. Moreover, in terms of numbers this is the largest analysis to date of an uncemented modular THA for salvage of proximal femoral fracture failures.

In summary, in patients with failure of internal fixation of trochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures and for whom THA is necessary, the use of a modular revision arthroplasty appears to be an attractive solution. The uncemented stem allows fixation distally in the femur. Our results indicate that stable fixation of the implant can be achieved with a good radiographic outcome. However, the rate of complications was high, especially from infection, which suggests that a more careful preoperative screening for low-virulence infections should be considered.

RJW: planning, collection of data, data analysis, and writing and editing of the manuscript. NPH: writing and editing of the manuscript. MB: analysis of radiographs and editing of the manuscript. JK: providing all the data from the Register, planning, and editing of the manuscript. AS: planning, collection of data, and editing of the manuscript.

We thank all the Swedish orthopedic surgeons who contributed data to the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. The study was supported by grants from the Karolinska Institute and Stockholm County Council.

No competing interests declared.

- Abouelela AA. Salvage of failed trochanteric fracture fixation using the Revitan curved cementless modular hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011; Dec 5. [Epub ahead of print]

- Bartonicek J, Fric V, Skala-Rosenbaum J, Dousa P. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head in pertrochanteric fractures: a report of 8 cases and a review of the literature. J Orthop Trauma 2007; 21: 229-36.

- Bohm P, Bischel O. Femoral revision with the Wagner SL revision stem : evaluation of one hundred and twenty-nine revisions followed for a mean of 4.8 years. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001; 83: 1023-31.

- Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, Riley LH, Jr. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1973; 55: 1629-32.

- Chirodian N, Arch B, Parker MJ. Sliding hip screw fixation of trochanteric hip fractures: outcome of 1024 procedures. Injury 2005; 36: 793-800.

- D’Arrigo C, Perugia D, Carcangiu A, Monaco E, Speranza A, Ferretti A. Hip arthroplasty for failed treatment of proximal femoral fractures. Int Orthop 2010; 34: 939-42.

- Engh CA, Glassman AH, Suthers KE. The case for porous-coated hip implants. The femoral side. Clin Orthop 1990; (261): 63-81.

- Haentjens P, Casteleyn PP, Opdecam P. Hip arthroplasty for failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures in the elderly patient. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1994; 113: 222-7.

- Haidukewych GJ, Israel TA, Berry DJ. Reverse obliquity fractures of the intertrochanteric region of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001; 83: 643-50.

- Haidukewych GJ, Berry DJ. Hip arthroplasty for salvage of failed treatment of intertrochanteric hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 5: 899-904.

- Hammad A, Abdel-Aal A, Said HG, Bakr H. Total hip arthroplasty following failure of dynamic hip screw fixation of fractures of the proximal femur. Acta Orthop Belg 2008; 74: 788-92.

- Jensen JS. Classification of trochanteric fractures. Acta Orthop Scand 1980; 51: 803-10.

- Jones HW, Johnston P, Parker M. Are short femoral nails superior to the sliding hip screw? A meta-analysis of 24 studies involving 3,279 fractures. Int Orthop 2006; 30: 69-78.

- Laffosse JM, Molinier F, Tricoire JL, Bonnevialle N, Chiron P, Puget J. Cementless modular hip arthroplasty as a salvage operation for failed internal fixation of trochanteric fractures in elderly patients. Acta Orthop Belg 2007; 73: 729-36.

- Mehlhoff T, Landon GC, Tullos HS. Total hip arthroplasty following failed internal fixation of hip fractures. Clin Orthop 1991; (269): 32-7.

- Mortazavi SM, R Greenky M, Bican O, Kane P, Parvizi J, Hozack WJ. Total hip arthroplasty after prior surgical treatment of hip fracture is it always challenging? J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (1): 31-6.

- Müller M, Nazarain S, Koch P. The comprehensive classification of fractures of the long bones. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer-Verlag; 1987; 120-1.

- OTA: Orthopaedic Trauma Association Committee for Coding and Classification. Fracture and Dislocation Compendium. J Orthop Trauma 1996; 10-Supp 1: 31-5.

- Seinsheimer F. Subtrochanteric fractures of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1978; 60: 300-6.

- Simpson AH, Varty K, Dodd CA. Sliding hip screws: modes of failure. Injury 1989; 20: 227-31.

- Sporer SM, Paprosky WG. Femoral fixation in the face of considerable bone loss: the use of modular stems. Clin Orthop 2004; (429): 227-31

- Stern R. Are there advances in the treatment of extracapsular hip fractures in the elderly? Injury (Suppl 3) 2007; 38: S77-87.

- Tabsh I, Waddell JP, Morton J. Total hip arthroplasty for complications of proximal femoral fractures. J Orthop Trauma 1997; 11: 166-9.

- Talmo CT, Bono JV. Treatment of intertrochanteric nonunion of the proximal femur using the S-ROM prosthesis. Orthopedics 2008; 31: 125.

- Thakur RR, Deshmukh AJ, Goyal A, Ranawat AS, Rasquinha VJ, Rodriguez JA. Management of failed trochanteric fracture fixation with cementless modular hip arthroplasty using a distally fixing stem. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26: 398-403.

- The Swedish National Hip Arthroplasty Register, Annual Report 2009, http://www.jru.orthop.gu.se/.

- Weiss RJ, Beckman MO, Enocson A, Schmalholz A, Stark A. Minimum 5-year follow-up of a cementless, modular, tapered stem in hip revision arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011a; 26 (1): 16-23.

- Weiss RJ, Stark A, Karrholm J. A modular cementless stem vs. cemented long-stem prostheses in revision surgery of the hip: a population-based study from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2011b; 82: 136-42.

- Zhang B, Chiu KY, Wang M. Hip arthroplasty for failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric fractures. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19: 329-33.