Abstract

Background and purpose Extracellular matrix remodeling is altered in rotator cuff tears, partly due to altered expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors. It is unclear whether this altered expression can be traced as changes in plasma protein levels. We measured the plasma levels of MMPs and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) in patients with rotator cuff tears and related changes in the pattern of MMP and TIMP levels to the extent of the rotator cuff tear.

Methods Blood samples were collected from 17 patients, median age 61 (39–77) years, with sonographically verified rotator cuff tears (partial- or full-thickness). These were compared with 16 age- and sex-matched control individuals with sonographically intact rotator cuffs. Plasma levels of MMPs and TIMPs were measured simultaneously using Luminex technology and ELISA.

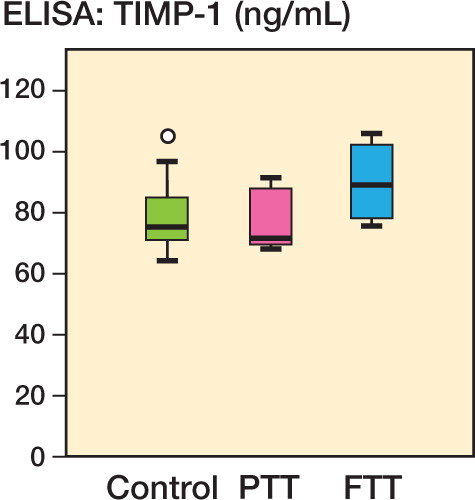

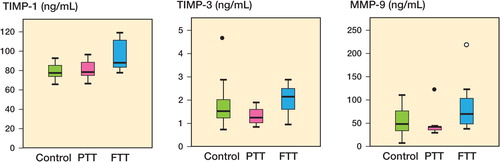

Results The plasma levels of TIMP-1 were elevated in patients with rotator cuff tears, especially in those with full-thickness tears. The levels of TIMP-1, TIMP-3, and MMP-9 were higher in patients with full-thickness tears than in those with partial-thickness tears, but only the TIMP-1 levels were significantly different from those in the controls.

Interpretation The observed elevation of TIMP-1 in plasma might reflect local pathological processes in or around the rotator cuff, or a genetic predisposition in these patients. That the levels of TIMP-1 and of certain MMPs were found to differ significantly between partial and full-thickness tears may reflect the extent of the lesion or different etiology and pathomechanisms.

The subacromial pain syndrome includes a range of disorders from reversible inflammation to massive rotator cuff tearing (Shindle et al. Citation2011). The etiology appears to be multifactorial, and several anatomic structures may be involved. Repetitive damage of the supraspinatus tendon by mechanical wear from the coraco-acromial ligament and the anterior acromion was described by Neer 1972, and for a long time it was considered the major cause of cuff tearing (Neer Citation1983). Others have reported age-related tendon degeneration, associated with alterations in extracellular matrix remodeling as a contributing factor (Lo et al. Citation2004, Millar et al. Citation2009, Pasternak and Aspenberg Citation2009, Shindle et al. Citation2011). Histopathological changes associated with rotator cuff tendinosis have been documented, but it is unclear whether they are a result of a subacromial impingement or an endogenous process, and whether tendinosis might predispose to tendon tears (Lo et al. Citation2004).

Regardless of whether mechanical or degenerative factors initiates tearing, there are alterations in the cellular and extracellular matrix (Gwilym et al. Citation2009). It has been suggested that genetic factors may influence apoptosis or regeneration (Gwilym et al. Citation2009, Shindle et al. Citation2011). Still, the molecular changes associated with rotator cuff tearing are largely unknown (Lo et al. Citation2004, Garofalo et al. Citation2011). Turnover of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a family of at least 24 zinc-dependent endopeptidases. The MMPs are classified according to their main degradative activity, into for example collagenases, gelatinases, and stromelysins (Pasternak and Aspenberg Citation2009). Their activity is regulated by endogenous inhibitors: tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). There are 4 known TIMPs, which reversibly inhibit all MMPs by 1:1 interaction with the zinc-binding site (Lo et al. Citation2004, Pasternak and Aspenberg Citation2009). MMP production is induced by factors such as cytokines and tumor necrosis factor-α. MMPs are secreted by connective tissue and inflammatory cells and then activated in the extracellular space (Garofalo et al. Citation2011). The composition of the ECM is dependent on the balance between MMPs and TIMPs (Lo et al. Citation2004, Pasternak and Aspenberg Citation2009, Garofalo et al. Citation2011). Levels of MMP mRNA and TIMP mRNA were found to be altered in biopsies from torn rotator cuff tendon (Lo et al. Citation2004). It is not known, however, whether these changes are causative or whether they are secondary to tendon tearing.

Studies on MMP and TIMP levels in patients with rotator cuff syndrome and cuff tears have used samples collected at surgery from the subacromial bursa, synovial fluid, or the tendons (Lo et al. Citation2004, Lakemeier et al. Citation2010, Shindle et al. Citation2011). To date, there have been no data on systemic levels. Alterations in MMP and TIMP levels in systemic blood samples have been identified in other musculoskeletal diseases such as Dupuytren’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, and fracture non-union, suggesting that alterations associated with rotator cuff disease may also be measurable systemically (Ulrich et al. Citation2003, Henle et al. Citation2005, Pasternak and Aspenberg Citation2009). In osteoarthritis, circulating MMP-3 has been suggested to be a marker of disease severity and has been used as a prognostic tool (Lohmander et al. Citation2005).

We measured plasma levels of MMPs and TIMPs in patients with rotator cuff tears and compared partial- and full-thickness tears, in order to find disease-associated changes in the expression patterns of MMP and TIMP.

Patients and methods

The study was approved by the local ethics committee in Linköping (reference M128-09). Consecutive patients with a rotator cuff tear were recruited for the study between January 2009 and February 2010. The inclusion criteria were: subacromial pain and shoulder dysfunction for at least 6 months and a partial or full-thickness rotator cuff tear verified by ultrasound. Exclusion criteria were: radiological or clinical signs of osteoarthritis in any joint, systemic joint disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, a fracture non-union, Dupuytren’s disease, frozen shoulder, tendinosis, or rupture of any tendons other than in the rotator cuff. In addition, the patient was asked if there was any history of the following disorders, in which case he or she was excluded: disorders of the spine such as disc disease, idiopathic scoliosis, spondylitis, cerebral or cardiovascular disease during the previous year, abdominal or bowel disease, surgery or trauma during the previous year, any infection during the previous month, malignancy, treatment for the last month with medications that might affect MMPs or TIMPs (tetracycline, bisphosphonates, anti-inflammatory drugs, statins), subacromial corticosteroid injection during the previous 6 months, or vigorous physical activity during the previous 24 h (Ulrich et al. Citation2003, Chirco et al. Citation2006, Pasternak and Aspenberg Citation2009, Bedi et al. Citation2010, Izidoro-Toledo et al. Citation2011, Rath et al. Citation2011). 17 patients (14 men) met the inclusion criteria. Median age was 61 (39–77) years. 6 patients recalled a traumatic onset of symptoms; 3 of them had partial-thickness tears and 3 had full-thickness tears. 14 had received subacromial injections of corticosteroid and local anesthetic (9 patients with a single injection and 5 with 2 injections) more than 6 months before inclusion. 16 age- and sex-matched control participants with no history of shoulder disease or any of the exclusion criteria were recruited by advertisement at Linköping University Hospital. No financial incentives were offered. All the participants in the study gave their written informed consent after receiving both oral and written information.

Ultrasound and clinical assessment

Before inclusion, the patients’ cuff tears and the control subjects’ intact rotator cuffs were verified by shoulder ultrasound, which was performed by an experienced radiologist at the Department of Radiology, Linköping University Hospital. A complete shoulder examination was done in all participants, including visualization of the long head of biceps and the acromioclavicular joint. The rotator cuff was evaluated in 2 planes with standardized positions and motions. The tears were categorized as partial-thickness tear (PTT) or full-thickness tear (FTT). The equipment used was a Siemens Acuson Sequoia 512 ultrasound machine (Acuson, Mountain View, CA) with a variable 8–10 MHz linear-array transducer.

The ultrasound examination showed that 2 of the FTT patients also had a subscapularis tear; the other 15 patients had isolated supraspinatus tears. All 17 patients had supraspinatus tears: 10 FTTs and 7 PTTs. No degeneration of the long head of biceps or signs of acromioclavicular osteoarthritis was found in any of the participants.

At inclusion, the patients were examined clinically and shoulder function was assessed using the Constant-Murley (1987) score. The score was similar in patients with PTTs (mean 41 (27–59)) and FTTs (mean 43 (26–56)). Mean age of patients with PTTs was 52 (39–65) years and mean age of patients with FTTs was 62 (42–77) years. 2 women had PPTs and 1 woman had FTT. 6 PTT patients and 8 FTT patients had received corticosteroid injections.

Blood samples and analysis of MMP and TIMP levels

4-mL venous blood samples were collected from all study participants and centrifuged for 10 min at 4,665 rpm and room temperature (2,749 g) to plasma. These samples were stored at –70 degrees until analysis.

Levels of MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, and MMP-9 were measured simultaneously using Fluorokine MultiAnalyte Profiling (F-MAP) kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The analysis was done in a Luminex 100 Bioanalyzer (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The luminex analysis can detect proforms, active forms, and TIMP-complexed forms of the respective MMPs. The samples were either diluted 1:3 or 1:15 and the dilution for which the range of all the samples fitted within the standard curve was chosen for the analysis. The 1:3 dilution was used for MMP-1 and MMP-7, and the 1:15 dilution was used for MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9. TIMP-1, TIMP-2, TIMP-3, and TIMP-4 were also analyzed simultaneously with a kit from R&D Systems. The samples were either diluted 1:12.5 or 1:50. Both dilutions for TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TIMP-4 fitted within the curve and a mean value of the dilutions was therefore used for analysis. TIMP-3 was expressed at lower levels and the samples only fitted within the standard curve at a dilution of 1:12.5. For 1 of the patients with an FTT, only analysis for MMPs could be done due to insufficient sample volume for TIMP analysis. The result for TIMP-1 was further confirmed using a sandwich ELISA kit (Quantikine; R&D Systems) and the samples were analyzed in duplicate.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. We first compared all patients (PTTs and FTTs) with controls, then FTTs were compared with PTTs, and both FTTs and PTTs were compared separately with controls. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. The statistical software package SPSS (version 18.0) was used for all analyses. The p-values should be interpreted with caution, as no correction for multiple comparisons was done.

Results

All tears vs. controls

Plasma levels of TIMP-1 were elevated in the patients with rupture (FTTs and PTTs) relative to the controls, as measured by Luminex (p = 0.04). However, this degree of significance was not found when the same analysis (all tears compared with controls) was repeated using ELISA method (p = 0.2). No other significant differences in plasma levels of the other MMPs or TIMPs were detected between these 2 groups.

Partial-thickness tears vs. controls

No significant differences were found between PTTs and controls for any of the MMPs or TIMPs analyzed with Luminex or ELISA.

Full-thickness tears vs. partial-thickness tears

The plasma levels of TIMP-1, TIMP-3, and MMP-9 were all higher in the patients with FTTs (p = 0.06, 0.02, and 0.03, respectively) than in those with PTTs, as measured by Luminex (, and and ).

Table 1. Plasma levels (ng/mL) in patients with rotator cuff tears and controls. Values are median (range) within each group

Figure 1. Plasma levels (in ng/mL) of TIMP-1, TIMP-3, and MMP-9 in controls, in patients with partial-thickness tears (PTT), and in patients with full-thickness tears (FTT), as measured by multiplex analysis. â—� Outlier (more than one and a half box lengths away). â—� Extreme outlier (more than three box lengths away).

Full-thickness tears vs. controls

Patients with FTTs had elevated plasma levels of TIMP-1 relative to the controls (p = 0.007), as measured by Luminex and with ELISA (p = 0.01). The elevated plasma levels of MMP-9 in these patients did not reach statistical significance, but the median value was 45% higher than in the controls (p = 0.09) ( and , and and ).

Table 2. Difference between all tears (partial-thickness and full-thickness) and controls. Median value for difference is measured in percent with 95% CI, based on non-parametric statistics

Discussion

The hypothesis in this study was that there would be a difference in the pattern of plasma concentrations of MMP and TIMP between patients and controls. Although TIMP-1 was clearly different, this is only 1 of 9 proteins, and the difference could be a random effect. Thus, our hypothesis could not be reliably confirmed and the results should be regarded as descriptive and hypothesis generating. Even so, the TIMP-1 findings were striking, and the difference between partial-thickness and full-thickness tears for 3 of the proteins might reflect biological differences between these conditions.

This is the first study to investigate the systemic levels of MMPs and TIMPs in rotator cuff tear patients. Our results can therefore only be discussed in relation to studies concerning these enzymes and other tendon affections that have been investigated more extensively. A higher level of TIMP-1 gene expression in human ruptured Achilles tendons than in normal tendons has been shown, suggesting the involvement of TIMP-1 in tendon rupture (Jones et al. Citation2006, Garofalo et al. Citation2011). Patients with an active Dupuytren’s contracture have higher TIMP-1 concentrations in their serum than have controls, and compared to Dupuytren patients in the residual phase (Ulrich et al. Citation2003). This suggests that even lesions of a limited size, like Dupuytren’s contracture, could have an influence on TIMP-1 concentrations in the blood. Ulrich et al. also showed that patients in the residual phase and controls had similar serum concentrations of TIMP-1. In addition, the same study showed that there were no significant differences in the serum levels of TIMP-2, MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in patients with Dupuytren’s contracture and in controls (Ulrich et al. Citation2003). These observations are in agreement with our findings—that TIMP-1 concentration (in particular) in the blood can reflect a local pathological condition and disease progression.

In fracture healing, serum levels of MMPs and TIMPs reflect posttraumatic processes, and they may aid in predicting outcome. Non-union of fractures has been suggested to be associated with—or even caused by—an altered balance of the MMP/TIMP system in favor of proteolytic activity (Henle et al. Citation2005). Other pathological processes such as atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and several forms of cancer also show specific time courses regarding concentrations of MMP and TIMP in serum (Chirco et al. Citation2006, Pasternak and Aspenberg Citation2009). Such pathological processes and also a rotator cuff tear are probably associated with a complex local biochemical environment. Factors such as age, gender, hormones, metabolic status, vascularization, and inflammatory response can influence expression of MMPs and TIMPs (Henle et al. Citation2005, Shindle et al. Citation2011). Our strict inclusion criteria were chosen in an attempt to minimize this cause of variation as much as possible.

There may be several reasons for alterations in MMP and TIMP levels in rotator cuff tear patients, such as local inflammation, tendon degeneration, altered mechanical loading, or genetic predisposition. Del Buono et al. (Citation2012) proposed that tendinopathy and tendon rupture may be separate entities with differences in symptoms, in expression of structural proteins and proteolytic enzymes, and in genetics. Our findings of significant differences in the plasma levels of TIMP-1, TIMP-3, and MMP-9 between partial-thickness and full-thickness rotator cuff tears might support this and reflect that partial-thickness tears and full-thickness tears might have different etiologies. In the present study, the partial tears were not subdivided between bursal and articular side tears but the literature suggests that articular-sided tears are associated with intrinsic degeneration and bursal-sided tears are often found in patients with impingment of the subacromial structures (Lakemeier et al. Citation2010). Lakemeier et al. (Citation2010) found higher MMP-1 and MMP-9 levels in tissue samples from articular-sided tears than bursal-sided tears, supporting the association between size and location of a tear and the expression of MMPs. It is believed that a partial tear may progress to a full-thickness tear, and it has been shown that cuff tears are more common with increasing age (Lakemeier et al. Citation2010). The differences in TIMP-1, TIMP-3, and MMP-9 levels between partial-thickness and full-thickness tears in our study might reflect increased tissue damage and tear size, but since patients with full-thickness tears were older, this may also have been due to increasing degenerative changes with age.

All of our patients complained of pain, and it is possible that such pain is a result of local inflammation, which in itself may affect the expression of MMPs. Substance P, a pain-mediating neurotransmitter capable of regulating the expression of MMPs and TIMPs, has been suggested to be responsible for disturbance in the homeostasis of the MMP and TIMP system in tendinopathy (Del Buono et al. Citation2012). A recent study has found that the expression of synovial inflammation, tissue degeneration, and expression of MMPs and TIMPs in the glenohumeral synovium correlate with tear size (Shindle et al. Citation2011). Our findings with higher levels of TIMP-1, TIMP-3, and MMP-9 in full-thickness tear patients (compared to partial-thickness tear patients) would appear to support this correlation. On the other hand, it appears that a full-thickness tear is not necessarily more painful than a partial-thickness tear, and pain is not necessarily part of the progression from a partial-thickness to a full-thickness tear (Jones et al. Citation2006, Garofalo et al. Citation2011). We found no difference in the Constant-Murley score between the partial-thickness and full-thickness tear groups that would have supported an association between pain-generating mechanisms and the levels of MMPs and TIMPs. Altered tension of the tendon in full-thickness tear rather than in partial-thickness tear may also play a role in the enzyme differences identified, since MMP expression in tendon cells is known to be modulated by mechanical loading. Both increased load and loss of tension may precede activation of destructive mechanisms leading to apoptosis and tendon degeneration (Jones et al. Citation2006, Millar et al. Citation2009, Garofalo et al. Citation2011, Shindle et al. Citation2011).

Genetic predisposition is another possible explanation of the altered MMP and TIMP levels (Kalichman and Hunter Citation2008, Shindle et al. Citation2011). For example, accelerated degeneration of intervertebral discs may be partly genetically predetermined, through MMPs (Kalichman and Hunter Citation2008). Painful Achilles tendinopathy has been associated with gene variants of MMP-3 (Raleigh et al. Citation2009). Siblings of patients with known rotator cuff tears have an increased incidence of rotator cuff tears and tear-size progression compared to controls (Harvie et al. Citation2004). These findings indicate that genetic factors are involved in the development and progression of rotator cuff tears (Gwilym et al. Citation2009), and genetic factors might influence the different plasma levels of MMPs and TIMPs in different degrees of tendon degeneration.

Corticosteroids have been found to have detrimental effects on the extracellular matrix in both in vitro and in vivo studies, but the extent of this effect is unknown (Tillander et al. Citation1999, Tempfer et al. Citation2009). The choice of excluding patients who had had a corticosteroid injection during the previous 6 months was a pragmatic choice based on the current literature, to minimize any potential effects of the steroids (Lo et al. Citation2004). It is unlikely that the plasma alterations in our study and the differences between partial-thickness and full-thickness tears can be explained by the steroid injections, since both groups received injections.

The selection of MMPs and TIMPs for analysis was based on the current literature (Ulrich et al. Citation2003, Lo et al. Citation2004, Pasternak et al. Citation2010). Several studies have found MMP-13 levels to be elevated in torn rotator cuff tendons, especially in full-thickness tears (Lo et al. Citation2004, Bedi et al. Citation2010, Garofalo et al. Citation2011). We did not measure MMP-13 because it is not possible to analyze it with the Multiplex method, and our previous experience with ELISA and MMP-13 was unsuccessful.

We measured the levels of MMP and TIMP in plasma because the levels in serum do not reliably reflect the circulating levels of these biomarkers (Gerlach et al. Citation2007). With the centrifugal speed we used, the plasma produced cannot be defined as platelet-poor plasma as some platelets may have been left in the samples when analyzed for MMPs and TIMPs. These platelets may have released some of the MMP-9 detected. All the samples were treated in the same way; thus, it is unlikely that the centrifugation would have had an effect on the difference in MMP-9 levels detected between groups.

The strengths of the present study are the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the matched controls, and the fact that we divided the tears into partial-thickness and full-thickness tears, which adds more information compared to other studies. Despite the fact that asymptomatic conditions may have affected tendons and connective tissues, the risk of this was equal for both groups. With strict exclusion criteria, we reduced this risk as far as possible and the only difference identified between the groups was the rotator cuff tears in the patient group.

One limitation of the study is that no samples from the subacromial tissue were taken to correlate the local levels of MMP and TIMP with circulating levels. However, only 6 of the patients with cuff tears underwent surgery, and surgical exploration would not have been justifiable for ethical reasons in the patients who were treated nonoperatively.

This study shows that alterations in the MMP and TIMP system may be measured systemically in patients with rotator cuff tears, and this knowledge may help in future development of diagnostic and prognostic disease markers. Further knowledge about the relationship between these potent enzymes and rotator cuff degeneration may also be valuable for potential biological modulation of the system.

Study design: HBH, PE, PA, and LA. Data collection: HBH. Data analysis: PE, PA, HBH, and LA. Statistical analysis: PE, PA, and HBH. Writing of the manuscript: HBH., PE, PA, and LA.

The authors thank Björn Pasternak MD, PhD for his contribution to the design of the study.

No competing interests declared.

- Bedi A, Fox A J, Kovacevic D, Deng X H, Warren R F, Rodeo S A. Doxycycline-mediated inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases improves healing after rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med 2010; 38 (2):308-17.

- Chirco R, Liu XW, Jung KK, Kim HR. Novel functions of TIMPs in cell signaling. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2006; 25 (1): 99-113.

- Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop 1987; (214): 160-4.

- Del Buono A, Oliva F, Longo UG, Rodeo SA, Orchard J, Denaro V, Metalloproteases and rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21 (2): 200-8.

- Garofalo R, Cesari E, Vinci E, Castagna A. Role of metalloproteinases in rotator cuff tear. Sports Med Arthrosc 2011; 19 (3):207-12.

- Gerlach RF, Demacq C, Jung K, Tanus-Santos JE. Rapid separation of serum does not avoid artificially higher matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 levels in serum versus plasma. Clin Biochem 2007; 40 (1-2): 119-23.

- Gwilym SE, Watkins B, Cooper CD, Harvie P, Auplish S, Pollard TC, Genetic influences in the progression of tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009; 91 (7): 915-7.

- Harvie P, Ostlere SJ, Teh J, McNally EG, Clipsham K, Burston BJ, Genetic influences in the aetiology of tears of the rotator cuff. Sibling risk of a full-thickness tear. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 86 (5):696-700.

- Henle P, Zimmermann G, Weiss S. Matrix metalloproteinases and failed fracture healing. Bone 2005; 37 (6): 791-8.

- Izidoro-Toledo TC, Guimaraes DA, Belo VA, Gerlach RF, Tanus-Santos JE. Effects of statins on matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous inhibitors in human endothelial cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2011; 383 (6): 547-54.

- Jones GC, Corps AN, Pennington CJ, Clark IM, Edwards DR, Bradley MM, Expression profiling of metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in normal and degenerate human achilles tendon. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54 (3): 832-42.

- Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. The genetics of intervertebral disc degeneration. Associated genes. Joint Bone Spine 2008; 75 (4): 388-96.

- Lakemeier S, Schwuchow SA, Peterlein CD, Foelsch C, Fuchs-Winkelmann S, Archontidou-Aprin E, Expression of matrix metalloproteinases 1, 3, and 9 in degenerated long head biceps tendon in the presence of rotator cuff tears: an immunohistological study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 271.

- Lo IK, Marchuk LL, Hollinshead R, Hart DA, Frank CB. Matrix metalloproteinase and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase mRNA levels are specifically altered in torn rotator cuff tendons. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32 (5): 1223-9.

- Lohmander LS, Brandt KD, Mazzuca SA, Katz BP, Larsson S, Struglics A, Use of the plasma stromelysin (matrix metalloproteinase 3) concentration to predict joint space narrowing in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52 (10): 3160-7.

- Millar NL, Wei AQ, Molloy TJ, Bonar F, Murrell GA. Cytokines and apoptosis in supraspinatus tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009; 91 (3):417-24.

- Neer CS, 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop 1983; (173): 70-7.

- Pasternak B, Aspenberg P. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors-diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities in orthopedics. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (6): 693-703.

- Pasternak B, Schepull T, Eliasson P, Aspenberg P. Elevation of systemic matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 in patients with a history of Achilles tendon rupture: pilot study. Br J Sports Med 2010; 44: 669-72.

- Raleigh SM, van der Merwe L, Ribbans WJ, Smith RK, Schwellnus MP, Collins M. Variants within the MMP3 gene are associated with Achilles tendinopathy: possible interaction with the COL5A1 gene. Br J Sports Med 2009; 43 (7): 514-20.

- Rath T, Roderfeld M, Blocher S, Rhode A, Basler T, Akineden O, Presence of intestinal Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) DNA is not associated with altered MMP expression in ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2011; 11:34.

- Shindle MK, Chen CC, Robertson C, Ditullio AE, Paulus MC, Clinton CM, Full-thickness supraspinatus tears are associated with more synovial inflammation and tissue degeneration than partial-thickness tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20 (6): 917-27.

- Tempfer H, Gehwolf R, Lehner C, Wagner A, Mtsariashvili M, Bauer HC, Effects of crystalline glucocorticoid triamcinolone acetonide on cultered human supraspinatus tendon cells. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (3): 357-62.

- Tillander B, Franzen LE, Karlsson MH, Norlin R. Effect of steroid injections on the rotator cuff: an experimental study in rats. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8 (3): 271-4.

- Ulrich D, Hrynyschyn K, Pallua N. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in sera and tissue of patients with Dupuytren’s disease. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 112 (5): 1279-86.