Abstract

Background and purpose Rotator cuff tears are associated with secondary rotator cuff muscle pathology, which is definitive for the prognosis of rotator cuff repair. There is little information regarding the early histological and immunohistochemical nature of these muscle changes in humans. We analyzed muscle biopsies from patients with supraspinatus tendon tears.

Methods Supraspinatus muscle biopsies were obtained from 24 patients undergoing arthroscopic repair of partial- or full-thickness supraspinatus tendon tears. Tissue was formalin-fixed and processed for histology (for assessment of fatty infiltration and other degenerative changes) or immunohistochemistry (to identify satellite cells (CD56+), proliferating cells (Ki67+), and myofibers containing predominantly type 1 or 2 myosin heavy chain (MHC)). Myofiber diameters and the relative content of MHC1 and MHC2 were determined morphometrically.

Results Degenerative changes were present in both patient groups (partial and full-thickness tears). Patients with full-thickness tears had a reduced density of satellite cells, fewer proliferating cells, atrophy of MHC1+ and MHC2+ myofibers, and reduced MHC1 content.

Interpretation Full-thickness tears show significantly reduced muscle proliferative capacity, myofiber atrophy, and loss of MHC1 content compared to partial-thickness supraspinatus tendon tears.

Rotator cuff tendon tears are accompanied by secondary changes in the rotator cuff muscles, including muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration. These muscular changes are especially pronounced in patients with large and massive tears, and are associated with reduced healing potential following rotator cuff repair and poor functional outcome. Whether rotator cuff muscle atrophy may partially or completely reverse after tendon repair is a matter of controversy, but fatty infiltration is undisputedly regarded as a later, irreversible change (Thomazeau et al. Citation1997, Goutallier et al. Citation2003, Gladstone et al. Citation2007).

Atrophy and fatty infiltration (also termed fatty degeneration) can be graded on CT-scans and MRI (Goutallier et al. Citation1994, Thomazeau et al. Citation1997, Fuchs et al. Citation1999). Whether this grading accurately reflects the true muscular changes is not clear. There is little information regarding early histological and immunohistochemical muscular changes accompanying rotator cuff tears in humans. The data that are available are mainly from animal studies (Gerber et al. Citation2004, Rubino et al. Citation2007, Liu et al. Citation2011, Kim et al. Citation2012) and a few cadaveric and biopsy studies (Nakagaki et al. Citation1996, Steinbacher et al. Citation2010).

Satellite cells are known to play a key role in the adaptive response of muscle to exercise, and in the maintenance of the regenerative capacity of muscle. Several studies have shown that a loss of mechanical stimulus (i.e. unloading) reduces the number of satellite cells in muscle; this reduction is thought to result from an impairment of proliferation and/or an increase in the level of satellite cell apoptosis, leading to reduced muscle mass and protein content (Darr and Schultz Citation1989, Matsuba et al. Citation2009) The possible association of satellite cells with rotator cuff muscle atrophy has not been studied.

The main objective of the present study was to compare the following histological and immunohistochemical features in the supraspinatus muscle of patients with partial-thickness rotator cuff tears (P) to those from patients with full-thickness tears (F): myofiber diameter, muscle protein content including myosin heavy chains 1 and 2 (MHC1/MHC2), degenerative changes including fatty infiltration, satellite cell number, proliferative activity, and apoptosis. We hypothesized that the group with full-thickness rotator cuff tears would have a reduced satellite cell number and a greater degree of myofiber atrophy.

Patients and methods

24 patients undergoing arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness (P) or full-thickness (F) supraspinatus tendon tears were included. The tears were classified by the operating surgeon intraoperatively. P tears were defined as articular- or bursal-side tears depending on the location of the tendon defect. F tears were classified according to Post et al. (Citation1983).

9 patients presented with P tears: mean age was 54 (45–60) years and 5 were men. There were 5 bursal- and 4 articular-side tears. The F group consisted of 15 patients: mean age was 58 (49–69) years and 10 were men. 13 tears were medium-sized and 2 were small. Median duration of symptoms in the P and F groups was similar (13 (6–24) months and 11 (1–72) months). In both groups, most of the tears were degenerative. In the F group, 4 of 9 patients reported a traumatic onset and 2 of 9 reported an “acute on chronic” onset. In the P group, 2 out of 7 patients reported a traumatic onset.

Preoperative MRIs were performed at different institutions. In the F group, 8 of 15 patients had atrophy of grade 1 according to Thomazeau et al. (Citation1997) and 1 of these 8 showed concomitant fatty infiltration of grade 1 according to a 5-stage grading system originally introduced by Goutallier et al. (Citation1994) for CT. Fuchs et al. (Citation1999) showed that this grading system was also reproducible on MRI. 2 patients in the P group had atrophy of grade 1; none showed fatty infiltration on MRI.

Patients suffering from systemic inflammatory disorders or diabetes and patients using nicotine were excluded. The study was approved by the regional committee for research ethics (1.2007.728), and informed, written consent was obtained from all participants.

Muscle biopsies of the supraspinatus were harvested arthroscopically from the fascial side of the supraspinatus muscle belly with a 3-mm biopsy punch passing through the subacromial space after completion of the rotator cuff repair (single-row technique). The samples were fixed in fresh 10% buffered formalin for 16–24 h at 4ºC and then dehydrated, mounted with fibers oriented transversely, and paraffin-embedded. The stained samples were scanned and evaluated using an Aperio Scancope XT (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA). The examiners were blind as to the identity of samples.

Histological evaluation of muscle degeneration

5-µm tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Degeneration was evaluated as previously described by studying the density of centrally placed nuclei (nuclei/mm2), presence or absence of vacuoles within myofibers, and fatty infiltration (the presence of lipid within myofibers, or of adipocytes surrounded by myofibers) (Scott et al. Citation2006).

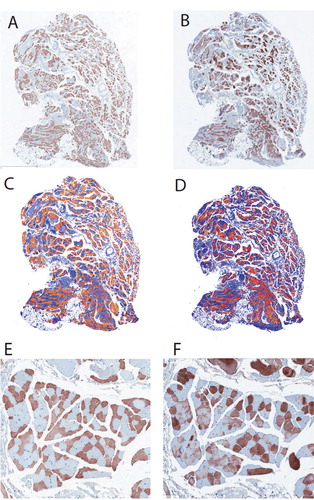

Myofiber size analysis and myofiber grouping

Immunostaining for myosin heavy chain isoforms MHC1 and MHC2 was carried out on serial sections using an automated immunohistochemistry unit (Discovery XT Ultramap DAB; Ventana Medical Systems, Oro Valley, AZ) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We recognized that there is a range of muscle fiber type characteristics; we therefore selected 2 mouse monoclonal antibodies, MYSNO2 and NOQ7.5.4D (Abcam catalogue numbers ab75370 and ab11083 respectively), which stain largely non-overlapping myofiber populations (). We defined the distinct and non-overlapping groups of muscle fibers detected by these 2 antibodies as MHC1+ and MHC2+, respectively. For ab75370, the primary antibody was incubated for 2 h at room temperature, whereas for ab11083, antigen retrieval with protease 1 for 8 min was used followed by 1 h of incubation at room temperature. Examination of stained muscle tissue sections confirmed that the 2 antibodies stained essentially mutually exclusive populations of muscle fibers. The smallest fiber diameter of MHC1+ and MHC2+ fibers in each sample were measured on a minimum of 100 fibers per sample. The inter-observer reliability of fiber size measurements was tested (r2 = 0.90). Grouping of ≥ 15 fiber bundles of the same type, suggestive of denervation-reinnervation, was noted (Lexell and Downham Citation1991).

Figure 1. Immunohistochemistry of supraspinatus muscle, showing MHC1+ (left panels) and MHC2+ fibers (right panels). A and B. Serial sections were stained with the 2 relevant antibodies (see Methods for details). C and D. The same pixel selection algorithm was used to select positive staining (orange/red) and negative staining (blue). E and F. Higher-magnification view of area shown in A and B. Note the generally non-overlapping pattern of MHC1 and MHC2 immunostaining. The vast majority of myofibers have been stained with one of the antibodies, but not both, while a very small minority have not been stained with either.

Quantification of MHC1 and MHC2

The amounts of MHC1 and 2 were expressed quantitatively using an automated method. Following a tuning protocol that was validated on a random selection of slides, positively stained pixels were digitally selected on all slides with the following parameters in ImageScope software (v 11.2, positive pixel count algorithm v 9.1): view width/height 1000, zoom 1, hue value 0.1, hue width 0.5, and color saturation threshold 0.04. The total positivity ratio of immunoreaction for the entire slide, i.e. the total number of positively stained pixels divided by the total number of pixels, resulted in a theoretical range from 0 (no staining) to 1.0 (every pixel stained), although in no case was every pixel stained (only myofibers were positively stained, while other aspects of the tissue were negative). Different intensities of staining were not analyzed separately.

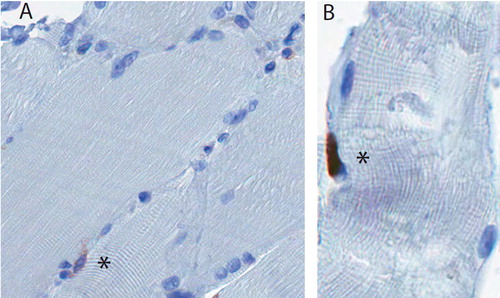

Satellite cells

For CD56 (neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), which is used as a marker of satellite cells), a rabbit antibody (EPR2566) was used (Epitomics cat. 2690-1) at a dilution of 1:100 and at room temperature. The control tissue was human glioma. Satellite cells were defined as showing NCAM-positive staining around the border of the cell, containing a nucleus, and being located at the periphery of a myofiber. We did not conduct special staining for the sarcolemma or the basal lamina. Positive cells were counted and the total number was divided by the muscle-sample area (mm²) (as calculated using the tracing tool in Aperio Imagescope software). The cells were counted and recounted after 2 days by the same blinded investigator. The intra-observer reliability coefficient (r2) was 0.76.

Proliferation

Proliferating nuclei were identified by the use of monoclonal mouse antibody to the Ki67 antigen. Heat-mediated antigen retrieval in EDTA buffer was performed. The primary antibody was incubated for 2 h at a dilution of 1:50. Tonsil tissue served as positive control. The number of positive cells located within or at the periphery of muscle fibers (and not in the connective tissue) was calculated and divided by the sample area (mm2) (as calculated using the tracing tool in Aperio Imagescope software) to allow direct comparison between samples.

Apoptosis

For assessment of apoptosis, we identified the activation of caspase-3, which is the common final executioner caspase for the apoptotic pathways. Sections were pretreated with EDTA buffer and incubated with a primary rabbit monoclonal antibody targeting cleaved caspase 3, 1:50 dilution (Asp 175; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) for 2 h. Human tonsil tissue served as control. We counted positively stained cells within or at the periphery of muscle fibers and calculated the density of positive cells per mm2 of muscle sample to allow direct comparison between samples.

Statistics

To compare the histological and immunohistochemical data of muscle samples from the P and F groups (fiber size, fiber type area ratio, CD56 and Ki67 density), Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test were used, depending on whether the samples satisfied the condition of equal variances. Any p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. To compare the presence of fatty infiltration in the P and F groups, Fisher’s exact test was used. Data were analyzed using online statistical software available through Vassar Stats (Vassar College, New York, NY). Reliability testing and correlation of variables in individual patients were conducted using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Data are expressed as mean (SD).

Results

General histological observations

There were no statistically significant differences in the general degenerative histological features of muscle from P tears and F tears. Fatty infiltration was present between fibers both in F tears (5 of 15 samples) and in P tears (1 of 9 samples) (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.2) with a tendency to be more pronounced in the F group. The density of centralized nuclei, a secondary indicator of histological degeneration, was not significantly different between the 2 groups (3.1 (3.1) vs. 1.78 (1.2); p = 0.4). The presence of vacuoles within myofibers was similar in both groups (5 of 15 vs. 3 of 8).

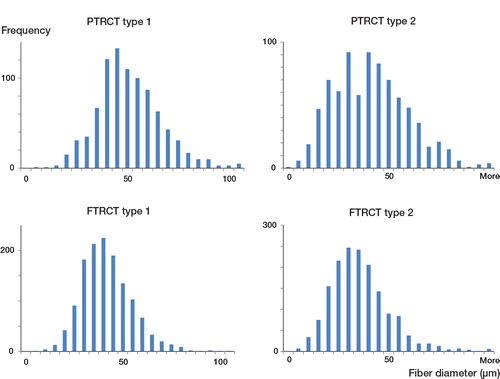

Myofiber size and grouping

F tears showed a statistically significantly smaller average diameter of fibers that were immunopositive either for MHC1 or MHC2, compared to P tears (). The mean fiber diameters of MHC1 and MHC2 myofibers in F tears were 39 (6.6) μm and 38 (8.8) μm, as compared to 48 (8.2) μm and 44 (12) μm in P tears (p < 0.01 for both MHC types). Fiber grouping was present in 4 patients with P tears (only affecting MHC1+ fibers) and in 9 patients with F tears (affecting both MHC1+ and MHC2+ fibers).

Figure 2. Sample fiber size distribution of type 1 and type 2 myofibers in the supraspinatus muscle of patients with partial-thickness rotator cuff tears (PTRCT, top panels) or full-thickness rotator cuff tears (FTRCT, bottom panels). Note the smaller size (a leftward shift in myofiber histogram) of both myofiber types in the FTRCT patients.

Muscle protein content

The MHC type 1 content was lower in F patients than in to P patients (0.40 (0.19) vs. 0.50 (10); p<0.05). Conversely, MHC type 2 content between the 2 groups was similar (F: 0.45 (0.13) vs. P: 0.47 (0.15)).

Satellite cells, proliferation ()

The number of cells showing CD56 expression, indicating the presence of satellite cells, was significantly less in F patients (3.1 (2.9) cells/mm2) than in P patients (8.1 (10.2) cells/mm2; p < 0.05). The number of proliferating cells (defined as Ki67+ nuclei) was 0.35/mm2 in F patients and 1.0/mm2 in P patients (p < 0.05), indicating a reduced number of proliferating cells in F tears.

Apoptosis

There was no detectable apoptosis involving the activation of caspase-3 in either sample group. In contrast, there was substantial apoptosis involving the activation of caspase-3 in control (human tonsil) tissue.

Discussion

We observed a statistically significant reduction in satellite cell number and reduced proliferative activity in the supraspinatus muscle of patients with a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, in comparison to those with a partial-thickness tear. This was also associated with muscle atrophy, which affected both MHC1+ and MHC2+ fibers without gross signs of fiber degeneration, and a tendency to fatty infiltration. These changes may illustrate a transition evolving by a pathomechanical pathway when tendon continuity is lost, resulting in loss of force transmission through the muscle (Meyer et al. Citation2004).

The MHC1 content was reduced in patients with an F tear, perhaps involving a shift in myofiber phenotype in which endurance-type fiber characteristics are lost. This finding is in line with previous reports describing a similar phenomenon in muscle-disuse atrophy (Jozsa et al. Citation1990, Grossman et al. Citation1998, Pette and Staron Citation2001), as opposed to the process of muscle ageing, which commonly involves a transition towards an increased type I fiber phenotype (Klitgaard et al. Citation1990, Korhonen et al. Citation2006, Lee et al. Citation2006). However, it must be acknowledged that we did not conduct a complete assessment of myofiber phenotypes but focused our attention on 2 of the predominant MHC types (1 and 2). Interestingly, our observations are in contrast to a study reporting that type 2 fibers are more prone to atrophy than type 1 fibers with progression of supraspinatus tendinopathy (Irlenbusch and Gansen Citation2003), whereas we report here that MHC1+ and MHC2+ fibers showed similar degrees of atrophy in F tears.

We found that muscle atrophy appears independently of degenerative muscle changes, which is in line with previous publications (Einarsson et al. Citation2011, Gumucio et al. Citation2012).

There were no signs of caspase-3-dependent apoptosis in the muscle samples examined, which may support the hypothesis that fiber atrophy is not caused by apoptosis or by other caspase-dependent processes (Steinbacher et al. Citation2010). However, alternative explanations are (1) that apoptosis occurred, but followed a caspase-independent pathway, or (2) that the cross-sectional nature of the present study missed a crucial time point when apoptosis of satellite cells or myofibers occurred (e.g directly following the loss of muscle tension after tendon rupture). There is very little information regarding the most important pathway in atrophy-induced apoptosis; there appears to be a selective activation of specific apoptosis pathways depending on age, muscle type, and the nature of the atrophying condition (Dupont-Versteegden Citation2005, Marzetti et al. Citation2010).

Despite the general absence of fatty infiltration on MRI, fat infiltration was in fact histologically confirmed in 5 of 15 patients with F tears, and in 1 of 9 patients with P tears. If fat accumulation occurs before it can be detected radiologically, this may favor early operation—i.e. to prevent establishment of significant irreversible fat infiltration which is associated with reduced healing potential.

Muscle biopsies from both P and F patients contained areas of fiber type grouping. Grouping of muscle fibers occurs in ageing human muscle and is thought to arise from a continuous, progressive process of denervation and partial reinnervation. This may be due to a slow, progressive neurogenic ageing process involving loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord and/or loss of functioning motor units in ageing human muscle (Tomonaga Citation1977, Lexell Citation1995). The age of patients with or without evidence of fiber type grouping was similar.

MRIs were performed at different institutions and this clearly is a limitation, allowing for variation in the quality of the examination and in the radiological evaluation of the extent of muscle changes. This precludes a conclusive evaluation of correlation between MRI findings and histological findings in our study. However, we found histological evidence of fatty infiltration despite the fact that this feature was not visible on the MRIs. This raises the question of whether there is a role for early fatty muscle infiltration in rotator cuff tendinopathy preceding more pronounced changes that are detectable on MRI. A comparative study between histology and MRI to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of MRI and CT to early muscle changes is yet to be published.

Another limitation inherent in muscle biopsy studies is that changes may not be distributed uniformly in the muscle. According to a previous study, the main changes of atrophy occur primarily at the fascial side of the muscle, whereas fatty infiltration is more pronounced on the scapular side (Meyer et al. Citation2005). Our biopsies were harvested arthroscopically, reaching the muscle from the subacromial space presumably representing the fascial side of the muscle belly.

With regard to the presence of fiber type, grouping electromyography—which was not performed—might have added valuable information.

Our findings should be interpreted with caution, due to the small number of patients and the limited size of the biopsies. Muscle atrophy, fatty infiltration, and fiber grouping may also develop without a rotator cuff tear, as part of the ageing of muscle tissue—a possibility which could have been evaluated further with an age-matched reference group without any rotator cuff pathology (Lexell Citation1995).

In summary, full-thickness rotator cuff tears are associated with a substantial reduction in satellite cell number and muscle proliferative capacity, general myofiber atrophy, and loss of MHC1 content compared to partial-thickness tears.

KL, OL and LE designed the clinical study (patient recruitment and biopsy procedure). KL assessed the patients and obtained the biopsy tissue. KL and AS designed and tested the methods, and conducted data collection and statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Julie Lorette and co-workers at the Center for Translational and Applied Genomics, Vancouver, Canada, and of Ingeborg Løstegaard Goverud at the Department of Pathology, Oslo University Hospital, Norway.

All the authors declare that there are no competing interests. AS received a Michael Smith Scholar award. The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by Lovisenberg Diaconal Hospital.

- Darr KC, Schultz E. Hindlimb suspension suppresses muscle growth and satellite cell proliferation. J Appl Physiol 1989; 67 (5): 1827-34.

- Dupont-Versteegden EE. Apoptosis in muscle atrophy: relevance to sarcopenia. Exp Gerontol 2005; 40 (6): 473-81.

- Einarsson F, Runesson E, Karlsson J, Friden J. Muscle biopsies from the supraspinatus in retracted rotator cuff tears respond normally to passive mechanical testing: a pilot study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011; 19 (3): 503-7.

- Fuchs B, Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Gerber C. Fatty degeneration of the muscles of the rotator cuff: assessment by computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8 (6): 599-605.

- Gerber C, Meyer DC, Schneeberger AG, Hoppeler H, von RB.Effect of tendon release and delayed repair on the structure of the muscles of the rotator cuff: an experimental study in sheep. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004; 86 (9): 1973-82.

- Gladstone JN, Bishop JY, Lo IK, Flatow EL. Fatty infiltration and atrophy of the rotator cuff do not improve after rotator cuff repair and correlate with poor functional outcome. Am J Sports Med 2007; 35 (5): 719-28.

- Goutallier D, Postel JM, Bernageau J, Lavau L, Voisin MC. Fatty muscle degeneration in cuff ruptures. Pre- and postoperative evaluation by CT scan. Clin Orthop 1994; (304): 78-83.

- Goutallier D, Postel JM, Gleyze P, Leguilloux P, Van DS. Influence of cuff muscle fatty degeneration on anatomic and functional outcomes after simple suture of full-thickness tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12 (6): 550-4.

- Grossman EJ, Roy RR, Talmadge RJ, Zhong H, Edgerton VR. Effects of inactivity on myosin heavy chain composition and size of rat soleus fibers. Muscle Nerve 1998; 21 (3): 375-89.

- Gumucio JP, Davis ME, Bradley JR, Stafford PL, Schiffman CJ, Lynch EB, Claflin DR, Bedi A, Mendias CL. Rotator cuff tear reduces muscle fiber specific force production and induces macrophage accumulation and autophagy. J Orthop Res 2012; 30 (12): 1963-70.

- Irlenbusch U, Gansen HK. Muscle biopsy investigations on neuromuscular insufficiency of the rotator cuff: a contribution to the functional impingement of the shoulder joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12 (5): 422-6.

- Jozsa L, Kannus P, Thoring J, Reffy A, Jarvinen M, Kvist M. The effect of tenotomy and immobilisation on intramuscular connective tissue. A morphometric and microscopic study in rat calf muscles. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1990; 72 (2): 293-7.

- Kim HM, Galatz LM, Lim C, Havlioglu N, Thomopoulos S. The effect of tear size and nerve injury on rotator cuff muscle fatty degeneration in a rodent animal model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21 (7): 847-58.

- Klitgaard H, Mantoni M, Schiaffino S, Ausoni S, Gorza L, Laurent-Winter C, Schnohr P, Saltin B. Function, morphology and protein expression of ageing skeletal muscle: a cross-sectional study of elderly men with different training backgrounds. Acta Physiol Scand 1990; 140 (1): 41-54.

- Korhonen MT, Cristea A, Alen M, Hakkinen K, Sipila S, Mero A, Viitasalo JT, Larsson L, Suominen H. Aging, muscle fiber type, and contractile function in sprint-trained athletes. J Appl Physiol 2006; 101 (3): 906-17.

- Lee WS, Cheung WH, Qin L, Tang N, Leung KS. Age-associated decrease of type IIA/B human skeletal muscle fibers. Clin Orthop 2006; (450): 231-7.

- Lexell J. Human aging, muscle mass, and fiber type composition. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995; 50 Spec No: 11-16.

- Lexell J, Downham DY. The occurrence of fibre-type grouping in healthy human muscle: a quantitative study of cross-sections of whole vastus lateralis from men between 15 and 83 years. Acta Neuropathol 1991; 81 (4): 377-81.

- Liu X, Manzano G, Kim HT, Feeley BT. A rat model of massive rotator cuff tears. J Orthop Res 2011; 29 (4): 588-95.

- Marzetti E, Hwang JC, Lees HA, Wohlgemuth SE, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Carter CS, Bernabei R, Leeuwenburgh C. Mitochondrial death effectors: relevance to sarcopenia and disuse muscle atrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010; 1800 (3): 235-44.

- Matsuba Y, Goto K, Morioka S, Naito T, Akema T, Hashimoto N, Sugiura T, Ohira Y, Beppu M, Yoshioka T. Gravitational unloading inhibits the regenerative potential of atrophied soleus muscle in mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009; 196 (3): 329-39.

- Meyer DC, Hoppeler H, von RB, Gerber C. A pathomechanical concept explains muscle loss and fatty muscular changes following surgical tendon release. J Orthop Res 2004; 22 (5): 1004-7.

- Meyer DC, Pirkl C, Pfirrmann CW, Zanetti M, Gerber C. Asymmetric atrophy of the supraspinatus muscle following tendon tear. J Orthop Res 2005; 23 (2): 254-8.

- Nakagaki K, Ozaki J, Tomita Y, Tamai S. Fatty degeneration in the supraspinatus muscle after rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1996; 5 (3): 194-200.

- Pette D, Staron RS. Transitions of muscle fiber phenotypic profiles. Histochem Cell Biol 2001; 115 (5): 359-72.

- Post M, Silver R, Singh M. Rotator cuff tear. Diagnosis and treatment. Clin Orthop 1983; (173): 78-91.

- Rubino LJ, Stills HF, Jr., Sprott DC, Crosby LA. Fatty infiltration of the torn rotator cuff worsens over time in a rabbit model. Arthroscopy 2007; 23 (7): 717-22.

- Scott A, Wang X, Road JD, Reid WD. Increased injury and intramuscular collagen of the diaphragm in COPD: autopsy observations. Eur Respir J 2006; 27 (1): 51-9.

- Steinbacher P, Tauber M, Kogler S, Stoiber W, Resch H, Sanger AM. Effects of rotator cuff ruptures on the cellular and intracellular composition of the human supraspinatus muscle. Tissue Cell 2010; 42 (1): 37-41.

- Thomazeau H, Boukobza E, Morcet N, Chaperon J, Langlais F. Prediction of rotator cuff repair results by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Orthop 1997; (344): 275-83.

- Tomonaga M. Histochemical and ultrastructural changes in senile human skeletal muscle. J Am Geriatr Soc 1977; 25 (3): 125-31.